Spatial Ability

Evolutionary Psychology, Workshop 10:

Female Advantage in Object Recall?

Learning Outcomes.

At the end of this session you should be able to:

1 . Review evidence concerning a possible female advantage in object recall.

2 . Assess possible sex differences in incidental memory for spatial locations.

3 . Collate the results from the group and discuss the results.

4 . Carry out an individual test of location memory using the computerised game 'Memory'.

Background.

Silverman & Eals (1992) and Eals & Silverman (1994) found that females were better able to recall objects and identify which objects had moved locations within an array.

This was conducted using pictures of familiar objects, pictures of uncommon objects, and real-life familiar and unfamiliar objects.

Female performance was better when incidental rather than directed recall was assessed especially for object location memory (item-moved task).

Several criticisms have been put forward.

1. Sex-Typicality of the Objects.

Some authors have pointed out that the sexes may differ in attentional processing, particularly if the objects to be remembered are thought to have masculine, feminine or neutral characteristics.

McGivern et al., (1997) examined visual recognition memory for stimuli which varied in terms of gender relatedness.

Adults and children were presented with male-, femaleand random-oriented stimuli. After this they received the same set of objects containing extra items and had to identify the added items.

Females at all ages were more accurate on random and female objects. Males performed no differently to females on identifying male items.

Cherney & Ryalls (1999).

Children had to recognise

18 gender-stereotyped toys, seen previously in a playroom.

Adults had to recall and identify the location of 30 gender-stereotyped objects previously seen in an office.

No sex differences emerged in either study.

However, males and females better remembered toys or objects that were congruent with their own sex.

Cherney & Ryalls (1999) p 313

Gallagher (1998).

Common items were first rated on their degree of masculinity or femininity. The 15 most masculine, feminine, and neutral items were used.

30 males and 30 females (15 in directed, and undirected conditions) were presented with an array of 33 objects (11 masculine, feminine and neutral).

Following a distracter task they had to identify added items, and items that had moved.

No sex differences emerged overall.

When divided into gender-types, males performed better on masculine items while females performed significantly better on feminine and neutral items.

There were no differences between incidental or directed learning conditions.

Possible Explanations?

1. The feminine objects may have been more distinctive .

24 new participants were shown pictures of all 45 items and rated them on their distinctiveness.

The most and least distinctive items that changed position in the item-moved task were feminine objects.

2. It is possible that it may be easier to detect a greater change in overall position than a small change .

The average distance moved for each item was also calculated. The feminine items moved significantly further than either masculine or neutral items.

Neave et al., (1999).

60 new participants (30 male, 30 female) carried out an item-moved task in which items exchanged places with other gender-specific items (i.e. female item-female item swaps).

Item distinctiveness and distance moved were controlled.

All participants performed this experiment under directed conditions.

No sex differences were found, but there were clear effects of distance, as items that moved furthest were identified more easily by both sexes.

2. Verbalisation of the Objects.

Chipman & Kimura (1999) pointed out that object recall tasks use stimuli which is heavily verbal in nature and a female advantage in verbal ability is often reported.

In their study male and female students performed several incidental and directed tests of object memory using verbal and non-verbal stimuli.

A female advantage emerged under both conditions but no sex difference emerged when using objects that were less easy to code verbally.

Lewin et al., (2001) reported that females performed better on tasks requiring verbal processing, the sexes did not differ in tests where verbalisation was not possible, and males performed better on tasks requiring visuospatial processing.

Verbalisation (continued).

Epting & Overman (1998) argued that the stimuli used by

Eals & Silverman (1994) resembled mechanical parts and could easily be given verbal labels (e.g. 'axle', 'sieve',

'piston' etc), using this version of the task they failed to find a sex difference.

Eals & Silverman,

1994, p99

3. How the Objects are Moved.

James & Kimura (1997) pointed out that in previous studies items are swapped with another item so the overall pattern of the array does not alter.

Shifting items to previously unfilled areas would change the appearance of the array.

They administered either a location-exchange or a locationshift task to males and females.

Females outperformed males on the location-exchange task

(as in the Silverman & Eals 1992 study) but there were no sex differences in the location-shift task.

If females are better able to recall the location of objects within an array then they should outperform males on all object recall tasks, but they clearly don't.

Location Shift Versus

Location Exchange.

From James &

Kimura, 1997 p161

4. Violation of Domain Specificity?

A key concept of evolutionary psychology is that the human cognitive architecture consists of a set of adaptations which are functionally specialised (domain specific) to solve specific problems.

If human females evolved object location mechanisms to locate plants and recall their position, then such abilities would not perhaps generalise to pictures of gender stereotypical objects manufactured within the past hundred or so years.

The use of pencil-and-paper tests lack ecological validity.

Ecologically-Valid Studies.

Neave et al (2000) tested the 'Gathering Hypothesis' using the identification of real plants within naturalistic arrays.

In 3 indoor tasks, and 2 outdoor tasks, participants were firstly shown a target plant.

They then had to locate examples of the target in an array of other plants.

Females recalled the locations of the stimuli faster than males and made fewer errors.

However, this study was simply concerned with recognition ability.

Example of the Test Stimuli

Target Array containing 6 targets

Time Taken to Locate Target Plants in an Indoor Array.

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

* **

A B C Tot

Plant

* males females

Correct Number of Target Plants

Located in the Outdoor Array.

3

2

1

0

5

4

*P<0.0

5

6

* males females

Neave et al., (2001) Study.

Participants viewed a target surrounded by 5 other plants

(attention was not drawn to these incidental targets).

5 examples of the target had to be found in a large array

(object recognition).

Following a delay, the same examples had to be found again (object location memory).

Finally, they were asked to identify the incidental exemplars within the array (incidental recognition).

The sexes did not differ in the time taken to recognise the targets, though females were faster.

Following the delay, females were significantly quicker at re-locating the same targets.

There was no sex difference in incidental recall.

Results.

Recognition

Object location

Incidental recognition /5

Males

69.7 sec

47.7 sec

2.0

Females

61.3 sec

34.3 sec

2.3

Summary of Ecologically-Valid Studies

There is some evidence for a small female superiority in plant recognition.

This is unlikely to be due to a speed/accuracy trade-off as females tend to be quicker and more accurate.

Females do appear to have a clearer advantage in object recall.

We found no evidence of an incidental advantage for females.

This preliminary data provides some support for the

‘Gathering Hypothesis’.

More ecologically-driven methodologies are required in this field of research.

Tasks.

1. Silverman & Eals (1992) object recall task .

You each presented 2 males and 2 females with the initial array and then gave them the item-added task, and itemmoved task.

We will collate data from each person and discuss the results.

2. 'Memory' task .

We will assess sex differences using the computerised game 'Memory' as described by McGivern et al., (1997).

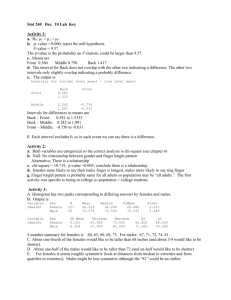

Results from this Session

Object Location task

Participants

MALES (N=40)

FEMALES (N=48)

Correct Items Added / 20 Correct Items Moved / 14

15.32

16.33

7.85

8.35

‘Memory’ Game

MALES (N=12)

Number of Misses

100.75

FEMALES (N=41) 93.75

Time Taken (s)

360.67

340.12

References.

Cherney, I.D., & Ryalls, B.O. (1999). Gender-linked differences in the incidental memory of children and adults.

Journal of

Experimental Child Psychology , 72: 305-328.

Chipman, K., & Kimura, D. (1998). An investigation of sex differences on incidental memory for verbal and pictorial material.

Learning and Individual Differences , 10: 259-272.

Epting, L.K., & Overman, W.H. (1998). Sex-sensitive tasks in men and women: a search for performance fluctuations across the menstrual cycle.

Behavioural Neuroscience , 112: 1304-1317.

Gallagher, P. (1998). The effects of item gender-stereotypes on the recall of object arrays. Undergaduate dissertation, Northumbria University.

James, T.W., & Kimura, D. (1996). Sex differences in remembering the locations of objects in an array: location-shifts versus location-exchanges.

163.

Evolution and Human Behaviour , 18: 155-

References (continued).

Lewin, C., Wolgers, G., & Herlitz, A. (2001). Sex differences favouring women in verbal but not in visuospatial episodic memory.

Neuropsychology , 15: 165-173.

McGivern, R.F., Huston, J.P., Byrd, D., King, T., Siegle, G.J., & Reilly, J.

(1997). Sex differences in visual recognition memory: support for sexrelated difference in attention in adults and children.

Brain and

Cognition , 34: 323-336.

Neave, N., Gallagher, P., & Hamilton, C. (1999). Female advantage in object recall? Some methodological considerations. Proceedings of the

British Psychological Society , 7: 133.

Neave, N., Hamilton, C., Hutton, L., Tildesley, N., Gallagher, P., &

Pickering, A.T. (2001). A female advantage in plant recognition and plant location memory: some preliminary observations of object location memory within an ecological context. Unpublished manuscript .

Neave, N., Hamilton, C., Hutton, L., Gallagher, P., & Pickering, A.

(2000). Female advantage in location memory using ecologically valid measures. Proceedings of the British Psychological Society , 8: 40.