- What Kids Can Do

advertisement

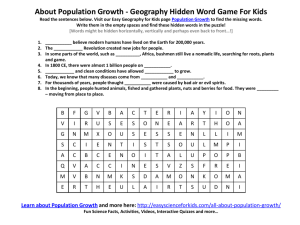

Outside is our school Russian mission, Alaska Youth Embrace Subsistence Education and Renew Survival for a Yupik Eskimo Community HONORING THE WORK OF YOUTH AND ELDERS IN RUSSIAN MISSION, Alaska What kids Can Do, Inc. © 2004 Miles of tundra surround Russian Mission, Alaska, population 307. A lime-green carpet of moss and lichen in summer, it quickly turns to ice and snow in the long winter. Accessible only by boat or charter airplane, this small Yupik Eskimo community is dramatically isolated, and closely knit. Still, the larger world leaves indelible marks. In the mid-1800’s, measles and influenza epidemics claimed half the Yupik people. In the 1900’s, village children were routinely taken away to attend boarding school in other states, and several generations missed the teachings of their elders. Today, villagers eke out a living from seasonal work, public assistance, and subsistence hunting. The loss of native traditions, combined with deep poverty, cast long shadows, especially for Russian Mission’s youth. But inside a ramshackle collection of buildings, a visionary education program is making school the kids’ favorite place to be. Since1998, Russian Mission’s students and faculty, joined by parents and other community members, have carved out a subsistence outdoor education program that joins the best of indigenous and modern ways—and lifts hope all around. The curriculum follows the students and the seasons closely. From third to eighth grade, kids learn about where and how they live. Third graders ski out to camp on snow. Seventh-grade girls paddle sixty miles on the Yukon to set up a moose hunting camp. The junior high spends three weeks camping in the fall, and makes shorter trips throughout the year. Eighth-grade graduation requirements include skiing thirty-four miles to the next town, snaring beaver, and starting a fire on snow. Students read, write, calculate and hypothesize, developing academic skills along the way. Sample Unit: Berry Picking Overview: Berry picking is an important part of the Yupik culture. This tradition not only provides food for people during camp, but has been an important part of maintaining their health during the long winter when Vitamin C is not available. The act of berry picking has also been a time for people to congregate, tell stories and deepen relationships with each other. Activities: 1. Study the plants of the area in the classroom (identify 5 berries, including 1 poisonous berry) 2. Utilize the knowledge of local experts to go to areas where berries have traditionally been harvested 3. Use the berries for traditional foods (making akutaq and making jelly) 4. Write 2 papers about berry picking and using the berries Content Standards: LEVEL: (narrative describing activity associated) (Specific Level) Writing: The class will write and edit two (2) extemporaneous compositions in a timed environment (W7.14): — One technical writing piece (scientific name, traditional use, etc…) — One essay piece about picking berries to process of using berries Science: Will learn to use a dichotomous key to find species of plants that grow in the local area (S3.6) Berry Picking (continued) P/S/S: The class will participate to pick the berries and make akutaq and jelly (P2.16, P2.19). Members of the class will practice skills to make and keep friends while picking berries and making traditional foods (P2.12) Yupik: The students will need to pick three (3) types of berries and insure that they are not poisonous (Y5.2) Health: The students will need to climb hills above 1000 ft. where the berries are found without hurting themselves (PE3.6) Technology: Create a PowerPoint presentation about making jelly and akutaq. (T4.6 and T4.7). Record whole process on digital video to be used later to make a “Year in Review.” Assessment: Writing projects will be assessed using the “6 traits of writing” rubric. Personal / Social / Skills will be assessed using a self-evaluation instrument, as well as by peer and teacher evaluations. An assessment for the Yupik portion will be based on elder, peer and teacher evaluations. The science and health content standards will be assessed using teacher created contents rubrics and rubric based presentations From “Creating a Subsistence-Based Curriculum” by Mike Hull, Principal, Russian Mission School Student journals Ice Fishing at 7 Mile Josh and I raced to the snow machine, but luckily I beat him there to sit in the back of the diver. When we reached 7 mile, I thought we were going to stay, but Max wanted to go to the end of the island. I saw my papa with 3 dead fish lying frozen on the ice. I wanted to stay with him and check what kind of bait he was using to catch his fish, but Max told me I had to stay with the group. So we went down and passed a huge mountain with lots of snow on it. I wished we could go up and slide all the way down the hill without hitting the trees. Rachel Evan, 15 Setting Blackfish Traps With Max Nickoli A couple of weeks ago we went to set blackfish snares. The weather outside was windy and cold. We traveled with the school’s trail touring 550 with the big yellow school bus. We traveled all the way to the second Tundra across the river and into the Kalaskag trail. We had to drill the ice with the school’s auger and to stick the blackfish snare in with a long stick near the beaver house. We marked the blackfish place by the sticks we had put into the hole by the house. While we were setting the traps, we were catching blackfish by hand and we almost caught more blackfish than we caught with the snares. We almost caught enough blackfish for a family. I learned how to ice pick, including how thick and wide to make the hole and how hard it is to ice pick the thick ice for a black fish hole. Vassily Takumjenak, 16 Making Akutaq Snow Caving Our second project in English class was to make some Eskimo ice cream "Akutaq." [First] we had to catch a fairly large pike. Then we cut up the pike and cooked it for 45 minutes. [Next] we put it in a bowl, squeezed all the juice out and broke the fish up in little pieces. While breaking the fish we looked for bones and threw them in the trash. We added Crisco to the fish to fluff [it] up. After we finished with the Crisco, we added some sugar. After the sugar dissolved, we added berries. The berries add the sweetness to your ice cream. After we mixed it all up, our akutaq was finished. Sean Alexie, 17 During the first week of March we went camping in snow caves with the jr. high and two teachers. We went ten miles out of town on the Kalskag trail. Kurt found a big snowdrift by some willows, [a good] spot to dig the cave. There were lots of shovels, some small and some big. The snow was hard as a rock. Kurt was happy when he was digging. Takako helped the girls make their cave. While everyone was digging some kids were fooling around. I was one of the kids who was fooling around. The sun set and it got dark. We all put on our warm stuff. There were no stars at night when I stayed up for a while. In the caves it was cold when we slept. Nick Changsak, 14 Spoken reflections “The thing I liked most was skinning the beavers. We’d do schoolwork about it first; read about it in articles, how big they’d get, how much food they eat, how much kids they have, how they build their houses in their habitat. We’d answer questions about them, then we’d go out and trap and skin the beaver. We’d put rock salt on the skin and rub it all over the place, and stretch it out in the sun. Afterwards, elders came in and taught us how to make boots and hats and gloves out of the beaver skin.” Rachel Evan, 15 “Cutting fish, building cabins, cutting wood, checking nets, shooting guns, ice fishing, eel fishing, trapping beaver with a snare, making a snow shelter, skinning moose, skiing, canoeing, gathering berries, starting fires....I think we are learning everything. We also dig snow caves. We dig a door out of a big pile of snow, dig till it’s deep enough to sleep in. We build a fire on the outside of the snow cave, to keep us warm. In the daytime we make long holes in the ice and then we swing the eel pole back and forth in the water to see if we can catch some eels. There’s nails in the pole to catch them.” Bupsie Kazevnikoff, 15 Student surveys Results: The survey of 41 households shows an increase in the use of most subsistence foods between last year and this year. Although moose seems about the same (each hunter is allowed one a year), there is a big increase in the number of caribou taken. Thirty-one last year and 49 this year. Many (16) felt they are eating more subsistence foods, and most (21) thought they were using about the same amount as in the past. Just four thought they were using less subsistence food. Results: Families provide 52% of the instruction in subsistence skills, the school provides 48%. Cooking, berry picking and moose hunting usually happen with the family. Traveling by canoe, skin sewing and winter survival activities happen mostly with the school. The surveys indicated that family usually teaches these skills when children are from age 4 to 10. The school provides subsistence training for ages 12 through 14. Program impacts Within the first year of the program, fourteen village kids who had dropped out of school decided to re-enroll. Some had left school as early as the third grade, and decided to give it another try. Standardized test scores have jumped dramatically, from among the lowest in the district, to the top third. The local police office reports a drop in crime in the village since the program began. While less quantifiable, the subsistence education program’s relational and social benefits are just as apparent. Camping and hunting in the unpredictable conditions of arctic weather builds a unique trust. Rachel Evan, 15, explains, “We had a better attitude, and we got to know the teachers better, when we were out camping than in the classroom. Instead of the teachers teaching us, we were teaching the teachers.” School secretary Millie Askoar, 49, has a birds-eye view on student life. A mother and grandmother, she takes the wellbeing of the community personally. She says, “I think the kids have grown a lot these last few years. We are working to bring back communication between families, with the youth camps. It has made the children much happier. I learned these things when I was growing. But these kids, somehow, I don’t know how, it got missed. So now the kids feel much better. It helps the whole community. It helps with getting to know ourselves, most of all.” Finally, the program puts food on the table for the village’s neediest members. When the kids go out hunting, they bring meat to the senior citizens first. Anutka Nickoli, 66, a retired health aide who lives alone explains, “I’m glad they go out, especially when they bring me moose meat. Me, I don’t hunt.” Getting to know themselves also means that students can more easily teach other students and work out interpersonal issues. Charlotte Alexie, a strong 13 year old with a ponytail and three diamond studs in her ears, says, “Girls learn just the same things boys do. Sometimes the boys get jealous and complain about us. They tell us only boys should learn how to hunt and trap, and girls should learn how to cook and sew. We always say, well, what if there were no boys in the world, how would we live? They don’t say anything else after we tell them that.” Roughly a third of the population of Russian Mission is in school right now, which means that the story of Russian Mission is a story of generational change. The students who are graduating now will be parents of their own children, and able to practice and teach subsistence as a part of daily life. Junior Chris Evan aims to study math in college, then return to teach at Russian Mission High School. Mike Hull , who has been the school principal for five years, describes his plans for the future of the program in plain terms: “What’s happening now is that the families are taking over the camps. Then the school teachers are guests there. That’s the goal, to have the villagers own it.” Why offer a subsistence-based curriculum? By Mike Hull, Principal, Russian Mission School The main reason for a village school to provide a subsistence-based curriculum is that villages are primarily subsistence communities and traditional skills are still necessary for young people to be able to provide for themselves. Those who assume the responsibility of educating the children of the village must provide them with the skills to live productively and responsibly in their community. Other reasons include: It strengthens the students’ sense of identity. Students learn their heritage by listening, reading and doing. Their way of life becomes the context in which all other academic skills are learned. It is sound pedagogy. It engages students, teachers and community members in activities that apply all learning to tasks that are real and of high interest. It makes use of the unique resources of the village heritage and environment. It necessitates parent and community involvement in all aspects of the educational program because they are the experts. It provides the opportunity for students to build relationships with the creatures who share their environment because they interact with their environment on a more frequent and intimate basis. Although more demanding than a textbook driven approach, it is certainly more enriching for students and staff because of the diversity of learning approaches and settings it provides. What is needed 1. Subsistence Environment – provides the location and the resources – plants and animals. 2. Students – with high interest in outdoor, hands-on activities. 3. Instructors: •Community members able to instruct young people in subsistence skills. •Teachers able to collaborate with community members to set priorities and organize activities, and who can build upon students’ experiences to develop reading, writing and mathematical skills. 4. The communities and students already have the basic materials for subsistence education. Supplemental materials can be acquired over time as the program grows. How to begin: First, go out there. Then, plan. Most of us are not trained in outdoor education. Get someone from the community who is adept in subsistence and have them take you and a group of students out to learn a skill that is new and challenging for you – but not overwhelming. And have the community person explain to the students what behavior is expected during this activity. Should you survive this initial experience, you will have all kinds of ideas on what you will and won’t do the next time, and you will generally be excited about the ways you discover to bring this experience that you share with your students back into the classroom to facilitate their growth in academic skills. And your response and insights will change every time you go out. “Mixing up culture is no new thing in the village. Kids dance to gangster rap music pumping from porch stereos on the town’s one rugged road—and when a flock of geese goes over, casting long shadows on the river, those same kids start making the guttural calls of geese. The geese call back, and a dialogue begins…” - Abe Louise Young, Writer, June 2004 Russian Mission School|P.O.Box 90, Russian Mission, AK 99657 Credits: Abe Louise Young, Marc Berger, Barbara Cervone, Mike Hull, and the students of Russian Mission, Alaska With generous support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation What Kids Can Do|P.O.Box 603252, Providence, RI 02906