Introduction - ALA Connect - American Library Association

advertisement

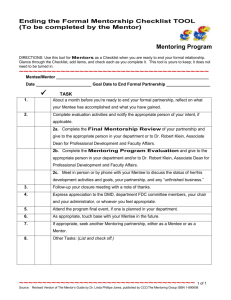

2012 ALA EMERGING LEADERS - TEAM E Mentoring Program Recommendations Our group partnered with the Association of Library Service to Children (ALSC) to make recommendations for the creation of ALSC’s new mentoring program. We researched mentoring programs, conducted a literature review on mentoring, and surveyed both ALSC members and non-members. This report is the compilation of our findings and recommendations. Kimberly CastleAlberts Rocco De Bonis Maria Pontillas Deborah Zimmerman Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………… 2 Background/Review of the Literature ….................................................................. 2 Mentoring Programs within ALA ………………………………………………………. 3 ALSC Mentoring Program Survey ……………………………………………………. 6 Survey Design & Marketing ……………………………………………...6 Survey Results ………………………………………………………….. 7 Recommendations for ALSC’s Mentoring Program …………………………………..16 References ……………………………………………………………………………… 19 Appendices: Appendix A: ALSC Mentoring Survey ……………………………………….. 20 Appendix B: Message Posted to Listservs …………………………………… 24 Appendix C: PDF File of Raw Survey Data ………………………………… 25 1 Introduction The Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) would like to launch a mentoring program designed to engage both new and experienced members. Reverse mentoring was identified early on as a way to achieve this aim. Reverse mentoring refers to a reciprocal arrangement in which new members serve not only as mentees but also mentors to senior members. In this arrangement seasoned professionals could provide career advice and guidance toward division participation, while new members expose mentors to new technology, social networking, and fresh perspectives on the field. In 2012, ALSC tasked ALA Emerging Leaders Team E with conducting background research on effective mentorship programs and drafting recommendations for developing the ALSC mentorship program. Team E has performed an extensive search of the academic literature regarding reverse mentor programs, contacted and studied mentor programs adopted by several other ALA divisions including LLAMA, YALSA, and NMRT as well as the programs of outside organizations such as the Southeastern Library Association (SELA). This preliminary research was used to create an online survey made available to new members, experienced members, and even nonmembers who are interested in potentially joining ALSC. In addition, the survey was based on and incorporated ALSC Core Competencies. Analysis of the survey results, studies of existing mentor programs, and the academic literature have been combined to produce a final recommendation for an ALSC Mentoring Program. Background: Review of the literature An extensive review of the literature on reverse mentorship revealed that the concept is already quite popular in the business community and offers many advantages over traditional mentoring. The most common rationale for employing a reverse mentoring program, as opposed to a traditional one, is that it allows younger employees to teach older employees new skills in technology and social networking. Hamaker (2009) cites a study by the Center for Work-Life Policy (CWLP) comparing the social networking habits of Generation Y/Millennials, people born between 1977 and 1997, with the habits of the Baby Boom Generation. The study found that 64 percent of Millennials participate in social networking on a regular basis as opposed to 20 percent of Baby Boomers. In addition, the study found that 40 percent of Baby Boomers regularly seek assistance with social networking, iTunes, and text messaging from Millennials. These findings led Time Warner to launch a Digital Reverse Mentoring Program pairing their executives with tech savvy college students. However, Baily (2009) points out that reverse mentorships can be far more than a tool for teaching IT to an older generation, and the fact that the business community has not realized this yet is a missed opportunity. For instance, Pieters (2011) defines reverse 2 mentoring as a type of employee development in which a more seasoned employee seeks the counsel of an employee with less experience but fresh perspectives, which de-emphasizes technological tutelage as the major input by the younger, lessexperienced mentee. A reverse mentorship can serve as a channel for fresh perspectives to reach the highest levels of ALSC leadership, especially if leaders in the group participate directly as mentors. Rai (2009) points out that reverse mentoring can be a way to stay contemporary in vision and strategy for young, modern “customers” by understanding their sensibilities (p. 22). Pairing experienced members to new members may lead to innovative initiatives and programming, more contemporary visions of the field, and expose older members to the hurdles new members face when trying to participate in or even understand the workings of the organization. Reverse mentoring has the potential to break down possible barriers between ALSC members of different ages, sex, sexual orientation, races, regions, and/or religions. Baily (2009) identifies generational differences as a common obstacle separating workers in business environments and proposes reverse mentorships as a possible solution. Phillips (2009) outlines Dell Computer Company’s plan to pair male senior executives with female middle managers in an attempt to offer male bosses a view of the challenges faced by women in their company. The author quotes the diversity manager of Dell in Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA) who argues that reverse mentoring works well in diversity areas such as sexual orientation, religious belief, and age. Biss and DuFrene (2006) argue that reverse mentoring is most successful if “mentoring pairs are carefully matched, programs contain sufficient structure, and goals are clearly established with progress toward them measured” (abstract). The importance of flexibility in the program is repeatedly asserted in the literature, in particular, the participants’ability to generate meeting topics, mode of communication, and timing (Mentoring for the Millennials, 2011, p. 80). Mentoring Programs within ALA In researching library mentoring programs we first turned our attention to ALA’s divisions, round tables, and ethnic caucuses. The following groups were contacted: American Association of School Librarians (AASL) Association for Library Collections and Technical Services (ALCTS) Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) American Indian Library Association (AILA) Association for Library Trustees, Advocates, Friends and Foundations (ALTAFF) Asian Pacific American Library Association (APALA) 3 Association of Research Libraries (ARL) Association of Specialized and Cooperative Library Agencies (ASCLA) Black Caucus of the American Library Association (BCALA) Chinese American Library Association (CALA) Library and Information Technology Association (LITA) Library Leadership & Management Association (LLAMA) New Members Round Table (NMRT) Public Library Association (PLA) The National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish-Speaking (REFORMA) Reference and User Services Association (RUSA) Southeastern Library Association (SELA) Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA) Of the number we contacted, more than half (ten out of eighteen) have existing mentoring programs already in place. All the groups use their websites as the primary way to promote their mentoring programs and have application materials and information readily available online. The most common program duration is one year and all the groups rely on some sort of committee to review applications and match mentors and mentees by library type, interests and, if possible, geographic proximity. After the formal application process and initial pairing, the mentoring programs assume a more relaxed and informal tone. Mentors/mentees become responsible for keeping in contact, with an expectation of communicating at least once a month. Participants most commonly use the phone, email, and/or other online programs like Skype. Only three programs (APALA, ARL, and BCALA) require the pairs to meet in person at least once during the year. LLAMA recently dropped their previous requirement that participants attend the annual conference, and they expect that this move to an all-virtual program will increase participation. The benchmarks used to measure success vary widely among the programs. Some organizations choose to stay actively involved. For example, according to their website, the Mentoring Committee of APALA contacts their mentors/mentees three times during the year. NMRT sends discussion topics monthly to their mentors/mentees via email. YALSA uses a self-guided approach and provides monthly discussion topics to participants in the form of a printed handbook that includes suggested resources and activities. YALSA also hosts optional quarterly chat sessions to connect mentors and mentees with others in the program. While some organizations take a more active role, most organizations have little interaction with their mentors/mentees during the program choosing instead to contact 4 them at the conclusion for feedback. For example, CALA does not monitor their mentoring duos during the year, but requires an evaluation survey at the end of the program. BCALA also conducts an end of the year review for each mentoring pair. Most programs require some sort of final program evaluation, but others do not set any standards for their participants. The types of evaluations required ranged from the formal (a completed evaluation form) to the more casual (feedback is given at the conclusion of the relationship). The following groups require a final program evaluation: ARL BCALA CALA NMRT YALSA The following groups do not require a final program evaluation: APALA LLAMA REFORMA When asked about benchmarks for their mentoring program, a contact at LLAMA said, “We let duos (mentor/mentee pairs) set their own benchmarks. If they consider their relationship a success, then we do as well.” Our research revealed certain commonalities among the mentoring programs in ALA. When asked what they liked the least about past mentoring experiences, a large majority of respondents stated factors that related to time. Most were disappointed that their mentor/mentee seemed to lack commitment due to a busy schedule. It appears as though while people are often anxious to participate in mentoring programs, many have little time to devote. Because of this, most organizations do not require heavy time commitments, hence the formal initial placement procedure and the seemingly informal and relaxed follow-through. Another common characteristic of all programs is that they attempt to pair mentor/mentees according to their area(s) of interest and, if possible, geographic location. A number of ALA mentoring programs deem it important that the mentor/mentee live relatively close to each other. Others do not mind a completely virtual experience. 5 Very few organizations could tell how many of their members are currently taking advantage of their mentoring programs. Estimates range from 10 to 40 members, a small percentage of the actual membership. Though these organizations maintain mentoring programs, promoting the programs is not a high priority. This may be due to a lack of qualified mentors or a lack of interest on the part of the organization. ALSC Mentoring Program Survey To gauge interest in and the feasibility of an ALSC mentoring program, ALA Emerging Leaders Team E designed and conducted a survey using Survey Monkey. The survey was open to both ASLC members and non-members. The survey was released on Monday, April 2, 2012, and survey responses were collected until Tuesday, April 24, 2012. 547 individuals completed the survey. Survey Design and Marketing The ALSC Mentoring Program Survey was comprised of 21 questions plus an extra open-ended question to capture additional comments. See Appendix A for a complete copy of the ALSC Mentoring Program Survey. The first part of the survey was designed to capture information about the respondents: library type, years of experience as a librarian, and ALSC membership status and experience. The second part of the survey was designed to gather data about respondents’ past experiences with mentoring programs. The third part of the survey was designed to gauge respondents’ interest in an ALSC mentoring program. The final section of the survey was designed to capture any additional respondent comments. The ALSC Mentoring Program Survey was conducted via Survey Monkey (http://www.surveymonkey.com/s/NGZ2MP7). When the survey was released on Monday, April 2, it was electronically marketed in a number of ways including blogs, Facebook, Twitter and email blasts through library related listservs. A blog post explaining the 2012 ALA Emerging Leaders Team E project and a link to the mentoring survey was posted on the ALSC blog (http://bit.ly/Hki6jO). A link to the survey and write-up of the Team E purpose was posted on the ALSC Facebook page (www.facebook.com/Associationforlibraryservicetochildren). Team E project members also posted links to the survey on their personal Facebook pages. A link to the Survey Monkey survey was tweeted via the ALSC Twitter account (@alscblog). Team E project members also retweeted this post on their personal Twitter accounts. 6 Team E project members posted messages about the Team E project and the mentoring survey link to numerous listservs. See Appendix B for a copy of the posted message. This message was posted to several listservs including but not limited to the following: PUB-YAC ALSC-L Kent State's Listserv Library Youth Services Listserv Ohio Public Library listserv (OPLIN) Ohio Library Council (OLC) Listserv Spectrum Scholars Listserv Emerging Leaders Listserv University of Washington iSchool Survey Results 547 individuals completed the ALSC Mentoring Survey. See Appendix C for the raw survey response data. Questions 1-3 of the survey gathered the following data about the respondents: library type, years of experience as a librarian, and ALSC membership status and experience. According to Question #1, a majority of the survey respondents worked in public libraries (75.4%). 1.4% 8.9% 9.9% Public Academic 4.5% School 75.4% Special None Figure 1: What Type of Library do you work in? (Question #1) 7 Based on responses to Question #2, we found that most survey respondents were experienced librarians. About 80% had at least 3 or more years of librarian experience. Only 20% of respondents were either in library school or had less than 2 years of librarian experience. Survey respondents were evenly split when it came to years of experience as a librarian. The most common response was 10 to 20 years of experience as a librarian followed closely by 20+ years, 5 to 10 year, and 3 to 5 years. 0 to 2 years 7.0% 3 to 5 years 12.8% 5 to 10 years 20.5% 19.0% 10 to 20 years 21.2% 19.5% 20+ years I am in library school Figure 2: How many years have you been a librarian? (Question #2) According to Question #3, though over 80% of respondents had 3 plus years of experience as a librarian, only 57.8% had been a member of ALSC for 0 to 5 years. 11.0% 0 to 2 years 12.6% 37.2% 3 to 5 years 5 to 10 years 18.6% 10 to 20 years 20.6% 20+ years 8 Figure 3: How many years have you been a member of the Association for Library Services to Children (ALSC)? (Question #3) Questions 4-8 of the survey were designed to gather data about respondents’ past experiences with mentoring programs. Question # 4 asked whether the respondent has ever been a mentor or mentee. It was found that most respondents had never participated in a mentoring program (42.7%). Of those who had participated in a mentoring program, 16.4% had been mentors and 14.3% had been a mentee. A quarter of respondents had experience being both the mentor and mentee at different times. Question #5 asked who organized the respondent’s mentoring program. Of those who had participated in a mentoring program in the past, only about half of those mentoring programs were organized by a place of employment, a professional organization or a library school. The other half of mentoring experiences took place at the initiative of the mentor/mentee themselves (15.2%) or via some other venue (37.8%). None of these Choices 37.8% %%% 177 Self Initiated 15.2% 71 Library School 49 Professional Organization 59 Place of Employment 10.5% % 12.6% 23.8% 111 0 50 100 150 200 Response Count Figure 4: Who organized the mentoring program in which you participated? (Question #5) Respondents who had participated in past mentoring programs enjoyed a number of things about being a mentor or mentee. According to open ended responses to 9 Question #7, the most common things enjoyed about the mentor/mentee relationship were the following: Being able to give back Passing on knowledge and influencing the next batch of educators Being able to ask questions that require specialized knowledge to answer Learning through my students and seeing them grow One of the best ways of learning and sharing in a work situation Being a mentee was good because I had someone outside of my workplace to ask questions and professional advice. Being a mentor is satisfying because you get to share things you’ve learned with another person. Loved getting or giving the support about things not taught in college classes (i.e. how to do a budget, how to order supplies, using the catalog, programming, etc.) Learning from others’ personal experiences The ability to network/networking Helping others to avoid pitfalls Gaining ideas, sharing, venting Constant feedback and guidance Professional insights, problem-solving, and shared energy Forming lasting relationships The ability to ask “dumb” questions and receive real-life advice According to Question #8, the things respondents least liked about past mentoring programs include: Limited time (not enough uninterrupted time to meet and communicate) Too much formal paperwork for the mentor Procedural, formal parts of being a mentor. Casual conversations work best. Lack of support by supervisors Not having clear expectations stated up front at the start of the mentoring relationship so that mentor/mentee did not have a clear mutual understanding of how the mentor/mentee relationship would work. Liked having an out-of-town mentor but would have liked to have met in person occasionally Questions 9-21 of the survey were designed to gauge respondents’ interest in an ALSC sponsored mentoring program. 80.2% of survey respondents said they would be interested in participating in a mentoring program through ALSC. Of those respondents 41.1% said they consider themselves a mentor while 26.3% said they identify themselves as mentees. 32.6% said they could serve as either the mentor or mentee. 10 32.6% 41.1% Mentor Mentee Either 26.3% Figure 5: Would you consider yourself a mentor or a mentee? (Question #10) According to Question #11, only 32.2% of respondents said that participants in the proposed ALSC mentoring program should be members of ALSC. Most said they did not care (48.2%) if participants were members or non-members of ALSC. If participating in an ALSC mentoring program, a majority of respondents do not care how they are matched with their mentor/mentee, but they do want to be matched with someone in the same field (see Figures 6 and 7). 16.4% 54.9% 28.8% Choosen by a committee Choose for myself No preference Figure 6: If participating in an ALSC mentoring program how would you prefer to be matched with your mentor/mentee? (Question #12) 11 Older, experience in the same field 5.1% Older, experience in a different field 33.5% 68.6% 4.9% Similar age, different experiences in the same field Similar age, experience in a different field Figure 7: As a potential mentee, who would you gain the most from as a mentor? (Question #13) Overall, respondents would be willing to mentor students currently in library school. 34.2% said they would do it, and 68.4% of respondents said they wouldn’t care if their mentee was still in library school. Respondents are overwhelmingly interested in a reverse mentorship program (see Figure 8). Reverse mentorship means that both mentor and mentee guide each other in their respective areas of strength. For example the mentor may be stronger in programming, but the mentee is stronger in technology. 12 7.8% Very interested 44.3% 47.8% Somewhat interested Not interested Figure 8: How interested are you in a “reverse” mentorship program? (Question #15) In general potential mentees want their mentors to live geographically close to them. 67.2% said it was very important or somewhat important for mentors and mentees to live geographically close to one another. According to Question #17, respondents want to gain (in order of importance) the following from a potential ALSC mentoring program: Learn a new skill set Become energized and reinvigorated with work Build my professional network Career guidance Recognition from my institution and/or supervisor Other hoped-for outcomes of an ALSC mentoring program are: Paying forward knowledge and advice about the profession Feeling like I’m not alone Gaining new viewpoints Recruitment Friendship Networking Advice/help for getting more involved with ALA and ALSC Wisdom – something that can only be passed on person-to-person Life balance guidance Opportunity to give back 13 Regarding ALSC’s Core Competencies, respondents ranked which skills they would like to develop in a mentoring program (Question #18). Specifically in ranked order the skills that respondents were most interested in developing though an ALSC mentoring relationship are: Advocacy, public relations, and networking skills Professionalism and professional development Administrative and management skills Programming skills Knowledge of materials Technology Communication skills User and reference services Knowledge of client group 85.2 % of respondents would like the ALSC mentorship program to be for a duration of 1 year or less (see Figure 8). 14.9% 20.8% 6 months 1 year 64.3% 2 years Figure 9: What duration do you think would be the most beneficial for a mentoring program? (Question #19) Respondents were split as to their preferred method of communication between mentor/mentee (see Figure 10). 61.6% prefer email while 32.4% prefer in-person communication. When allowed to expand on their preferred communication method many respondents said all of the above or some combination of the answer choices depending on the situation. For example, during the year the mentor/mentee might communicate via email and Skype but may make an effort to get together at ALA or PLA conferences. 14 4.0% Phone Email 32.4% 51.5% Skype/Other Meeting Software In-person 12.1% Figure 10: Preferred method of communication in a mentoring relationship (Question #20) In conclusion, the majority of survey respondents were public librarians with some experience in the library field. They also have some previous experience in mentoring programs. Potential mentors prize the opportunity to help others learn and grow in the profession. Past mentees have learned a great deal from previous mentoring experiences, in both professional and non-professional settings. They are interested in participating in an ALSC mentoring program, but want a mentor with experience in their own field or area of focus. They do not care how they are matched with their mentor/mentee but want that person to be located geographically close to them. What they most hope to gain from an ALSC mentoring program is learning a new skill set and being re-energized at work. In relation to ALSC’s Core Competencies, respondents want an ALSC mentoring program to address the following areas: Advocacy, public relations, and networking skills Professionalism and professional development Administrative and management skills Additional comments/suggestions captured at the end of the survey include: “Mentoring helped me very much, and I’d like to pass the gift on.” “A person can benefit for several different mentors at different times. And each brings something different to the table…” 15 “I’m so pleased ALSC is pursuing this. It was hard to make choices. I think anyone truly interested in this would adapt to the parameters you set up for time period, method of communication, etc. Thank you.” Thank you for thinking of this type of program. Since library school it’s been hard to find a mentor that would help me to grow in some of the areas I wasn’t trained in then. This sounds like a great opportunity for professional development for both those new to the field and for those who have been in it for a while.” Recommendations for ALSC’s Mentoring Program: Given our research and the data provided by the survey, we feel confident in making the following recommendations: 1. Create identifiable benchmarks and written goals with the help of mentors/mentees: For formal mentoring programs, clearly stated objectives and goals guide mentors and mentees in the best ways to use their time together. According to Biss and DuFrene (2006) reverse mentoring is most successful when pairs are carefully matched, the program is well structured, clear goals are established, and progress is regularly measured. When a mentor/mentee has a hand in setting those benchmarks/goals, they have a tailored mentoring experience that works best for all parties. 2. Supply suggested activities: a. SELA has a longstanding mentoring program and a wealth of information for their participants online. Of particular note is the “Suggested Activities for Mentors and Mentees” in section J. Some suggested activities listed include the following: keeping a mentoring journal, providing resume feedback, and writing an article on their experience. b. Include activities and discussion topics that would help the mentee learn about aspects of librarianship in the “real world”. This could include activities and topics that are more experience than theory-based. When asked what the mentors/mentees liked the best about their experience, many respondents mentioned that they shared things that they never learned in library school. 3. Allow the mentor/mentee to set the communication schedule/methods. Some of the survey participants preferred a more in-person relationship while others were content with a completely virtual relationship. A combination of both methods seemed to be the most popular response. Due to the recession, many librarians do not have the time or the funds to devote to professional 16 development opportunities. Allowing mentor pairs to have some flexibility is likely to increase participation in ALSC’s program. The importance of flexibility in the program is repeatedly asserted in the literature, in particular, participants’ ability to generate meeting topics, mode of communication, and timing (Mentoring for Millennials, 2011, p. 80). 4. Require that the mentor be a member of ALSC, but allow non-members to sign up as mentees. Based on the survey results, most participants took this stance when asked about membership requirements. This may be a good way for potential ALSC members to sample some of the benefits of membership. 5. Offer an online webinar and/or a workshop at Midwinter or Annual about how to get the most out of a mentoring relationship. PLA offered a workshop at their conference in March of 2012 called “Give ‘em a Shot! Mentoring and Providing Professional Opportunities for the Next Generation of Librarians”. ALSC could tailor this workshop to address the needs/concerns of children’s librarians. 6. Mentors should be required to watch a training video via webinar on how to be an effective mentor (e.g. what to expect, how to guide a mentee, what their responsibilities would be). Some of the complaints that were received about mentoring programs were that the mentor did not seem prepared or interested enough to guide a mentee. Some mentors stated, in fact, that they did not feel prepared themselves. A webinar, wiki, or handout could be given to the mentee so that they would know what to expect as well. NMRT currently has such resources outlined on their website: http://bit.ly/LhOc0W. 7. Partner with other library associations. One option would be to work in tandem with the New Members Round Table (NMRT) to help recruit new professionals to the field. RUSA-STARS and LITA are currently doing this. 8. Require a written evaluation/report at the end of the formal mentoring period. While the program itself should be kept fairly casual, an evaluation of the mentor and mentee’s experiences will help ALSC to keep improving the program. 9. Encourage ALSC leaders to participate. Lastly and most importantly, reverse mentorship can serve as a channel for fresh perspectives to reach the highest levels of ALSC leadership, especially if ALSC leaders participate directly as mentors. Pairing experienced members with new members may lead to innovative initiatives and programming, more contemporary visions of the field, 17 and expose older members to the hurdles new members face when trying to participate in or even understand the workings of the organization. The literature consistently promotes reverse mentoring as a means to expose experienced mentors to new technology and social media. 18 References Baily, C. (2009). Reverse intergenerational learning: a missed opportunity? AI & Society, 23(1), 111-115. doi:10.1007/s00146-007-0169-3 Biss, J. L., & DuFrene, D. D. (2006). An Examination of Reverse Mentoring in the Workplace. Business Education Digest, (15), 30-41. Hamaker, C. (2009). An Example in Their Youth. Rural Telecom, 28(5), 9. Mentoring for the Millennials. (2011). T+D, 65(6), 80. Phillips, L. (2009). Dell to roll out 'reverse mentoring.'. People Management, 15(22), 12. Pieters, B. (2011). Reverse Mentoring: Fresh Perspectives from Future Leaders. Profiles In Diversity Journal, 13(6), 68. Rai, S. (2009). Young at Heart. Forbes Asia, 5(10), 22-25. 19 Appendix A: ALSC Mentoring Program Survey Team E of the Emerging Leaders Class of 2012 has been tasked with writing a recommendation pertaining to developing a mentoring program for members of the Association for Library Services to Children (ALSC). This survey is being conducted in order to monitor the interest of ALSC member in such a program. Please take a moment to fill out this survey and submit it by Tuesday, April 24 th, 2012. Even though this survey is anonymous your responses may be used for academic purposes. Thank you for your participation! 1. What type of library do you work in? - Public - Academic - School - Special - None - Other (please specify) 2. How many years have you been a librarian? - 0 to 2 years - 3 to 5 years - 5 to 10 years - 10 to 20 years - 20+ years - I’m in library school. - I am not a librarian. (Please explain) 3. How many years have you been a member of the Association for Library Services to Children (ALSC)? - 0 to 2 years - 3 to 5 years - 5 to 10 years - 10 to 20 years - 20+ years - I am not a member of ALSC. (Please specify any other divisions you are a member of.) 4. Have you ever been: 20 - A mentor (A mentor is defined as “a teacher, guide or advisor who shares information with a mentee.”) A mentee A mentee is defined as “a person who receives the coaching of a mentor,” sometimes called a protégé.) Both Neither 5. Who organized the mentoring program in which you participated? - Place of employment - Professional organization - Library School - My mentor and I set it up ourselves - None of the above 6. Would you please tell us a little more about your response to question 5 (i.e. the name of your place of employment, association, school, etc.)? 7. What did you like the best about being a mentor/mentee? 8. What did you like the least about being a mentor/mentee? 9. Would you be interested in participating in a mentoring program through ALSC? - Yes - No - Maybe (please explain) 10. If so, would you consider yourself a mentor or a mentee? - Mentor - Mentee - Either 11. Should all participants be members of ALSC? - Yes - No - I don’t have a preference 12. If you were to participate in a mentoring program from ALSC, would you prefer to be matched with a mentor/mentee that is chosen by a committee, or would you rather choose yourself from a database of participants? - Chosen by a committee - Choose myself 21 - I don’t have a preference 13. As a potential mentee, would you gain the most from a mentor who is: - Older with experience in the same field as you. Older with experience in a different field from you. A similar age with different experiences in the same field as you. A similar age with experience in a different field from you. 14. If you were a mentor, would you be open to mentoring students in library school or would you prefer to only mentor those currently working in a library? - I would be open to mentoring library school students I would prefer to only mentor those working in the field I don’t have a preference 15. How interested would you be in “reverse” mentorship? (Meaning that both mentor and mentee guide each other in their respective areas of strength. For example, the mentor may be stronger in programming, but the mentee is stronger in technology.) - Very interested Somewhat interested Not interested 16. As a potential mentee, how important is it that your mentor lives geographically close to you? - Very important Somewhat important Not important 17. What would you hope to gain from a mentoring program? (Please rank them from 1-5, with 1 being the most important.) - build my professional network learn a new skill set become energized and re-invigorated with work career guidance recognition from my institution and/or supervisor other (please specify) 18. Which of the following skills are you most interested in developing through your mentoring relationship? (Please rank them from 1 to 9, with 1 being “most interested”.) 22 - Knowledge of client group Administrative & Management Skills Communication Skills Knowledge of Materials User and Reference Services Programming Skills Advocacy, Public Relations, and Networking Skills Professionalism and professional development Technology 19. What duration do you think would be the most beneficial for a mentoring program? - 6 months 1 year 2 years Other (please specify) 20. What would you preferred method of communication be in a mentoring relationship? - Phone Email Skype or other meeting software In-person Other (please specify) 21. Please list any other comments below. 23 Appendix B: Message Posted to Listervs about the Mentoring Survey Please excuse cross postings. The 2012 ALA Emerging Leaders Team E is researching the planning and implementation of a mentoring program for the Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). As part of the research, the team is asking ALSC members and non-members to complete a 21-question survey that studies the interest and feasibility of such a program. To take this survey, please click on the link below. The survey should take no more than 5-10 minutes to complete. The deadline to take the survey is Tuesday, April 24. http://www.surveymonkey.com/s/NGZ2MP7 Please contact Kim Alberts at kim.alberts@hudson.lib.oh.us with any questions about this survey. Thank you in advance for your help. Sincerely, 2012 ALA Emerging Leaders Team E 24 Appendix C: Raw Survey Monkey Survey Results See separate survey results PDF file. 25