Clayton Miles Lehmann - University of Nebraska Omaha

advertisement

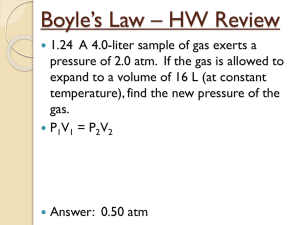

Plus ultra and the Far Side of the World: The Imperial Ideal of Charles V Clayton Miles Lehmann The University of South Dakota Most sovran lord: the discovery of the Indies represents the greatest event since the creation of the world, excepting the incarnation and death of its creator [for their] magnificence and size almost equals that of the Old World of Europe, Africa, and Asia. . . . Never has any nation extended its customs, language, and arms as has Spain, nor has it carried its arms so far by sea and land. . . . God willed that your vassals discover the Indies in your time so that you might convert them to his holy law. . . . The pope authorized the conquest and conversion and you took literally your motto, Plus ultra, which you understood to refer to the lordship of the New World. Therefore your majesty rightly favors the conquest and the conquerors while ensuring the welfare of the conquered.1 So Francisco López de Gómara begins his General History of the Indies in 1552 with a dedication to Emperor Charles V, king of Spain and sovran of vast realms in Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. He emphasizes the dazzling novelty and size of the New World, the role of Spanish arms, and the tradition of crusading, and he justifies Charles's claim on the Indies by divine sanction, papal authorization, and the need to convert the natives to Christianity. Charles put into action his imperial motto—plus ultra: “further beyond!” He thereby confirms the work of the conquistadores, protects the conquered, and enjoys the benefits of holding such a large, fruitful, and interesting land. Gómara thus prompts reflection on how Europeans understood the new discoveries to fit into Charles's imperial ideal. The motto plus ultra and the pillars of Hercules associated with it in the emperor's famous emblem (fig 1) will introduce us to these reflections. I The Imperial Device2 1 Figure 1: Coat of Arms of Charles V (Wikipedia Commons). The device shows the twin columns of Hercules rising out of the sea; a banner carries the motto in the language of the court, French: plus oultre. Other symbols commonly appear with the columns and the motto: Hercules' club or lion cap, a coat of arms or symbols of Charles's various realms. A courtier in Charles's Burgundian court in the Netherlands invented the device about 1516, shortly after Charles received the succession to the throne of Castile and Aragon after the death of his grandfather Ferdinand. The device alludes to the potential of the young, sixteen-year-old monarch to realize a great future from his origin as the Habsburg Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, and now King of Spain. It probably also alludes to the discoveries in the Indies that belonged to the Crown of Castile, but in 1516 the discoveries scarcely went beyond the Caribbean; Balbao had only in 1513 crossed the Isthmus of Panama. As I shall point out later, only in the 1530s did Europeans really come to realize the extent of the new continents and fit them into their geography. At any rate, when Charles went to Spain for the first time in September of 1517 the sail of his ship carried the new device.3 Evidently due to the anti-Flemish feeling among Charles's Spanish subjects, his advisers recast the motto in a Greek and a Latin version (Nondum: “not yet”) in the second attestation at a tournament in Valladolid in October. 4 In January 1518 we see for the first time the motto plus ultra on the title page of a book published in Murcia (fig 2).5 2 Figure 2: Title page, Francisco de Castilla, Theorica de virtudes en copias de arte humilde con cōmento (Murcia: G Costilla, 1518). This ítem is reproduced by permission of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California, RB 66878. In January 1519 the device decorated his seat in the choir stall of the cathedral at Barcelona on the occasion of the first meeting of the chivalric Order of the Golden Fleece held outside Burgundy (fig 3).6 3 Figure 3: Cathedral of Barcelona, Chapel of the Order of the Golden Fleece, Detail of the Columnar Device of Charles V (1519). By permission of Rafael Domínguez Casas. The French plus oultre literally means “further beyond.” When translated into Spanish it appears as más allá or allende and in German noch weiter. In Latin one makes a comparative by inflection, so to turn ultra, “beyond,” into “further beyond” one would use ulterior. Instead our Flemish courtiers used the defective plus ultra, where the substantive plus (“more”) becomes an adverb as in French. We see here a calque, where French contaminates the Latin, though vulgar Latin does admit this usage. Perhaps Charles's advisors thought the phrase plus ultra stronger than the word ulterior. German pedantry insisted on ulterior for a while in the early 20s until plus ultra became standard.7 In Italy people were also confused about the proper form for a time: an exquisite writing desk made for Charles in Bologna about 1530 and now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 4 has the partially Latinized plus oultra (fig 4).8 Figure 4: Plus Oultra Writing Cabinet of Charles V, ca 1530. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. According to ancient authors such as Herodotus (2.33; 4.8, 12), Aristotle (Meteorology 2.1), Diodorus Siculus (5.20), and Strabo (1.4.5; 3.5.5-6), Heracles set up the columns at the western limit of Europe and Africa in order to commemorate his travels and achievements. Strabo saw the bronze columns in a temple at Cádiz, though he denied their authenticity. The columns of Hercules became an indicator of direction toward or way from and location at, around, and beyond the Straits of Gibraltar. Pindar added a moral interpretation when he made the columns Heracles's warning to men not to attempt to go beyond them (Nemean 3; Olympian 3.41-45). Thereby the columns become a marker of moral restraint. The notion that the columns mark a boundary beyond which no one should venture culminates with Dante's interview with Odysseus in Inferno (26.108-9). Odysseus took his men beyond the point dov' Ercule segnò li suoi riguardi 108 where Hercules marked off the limits, acció che l'uom più oltre non si metta; 109 warning all men to go no farther.9 Note the very first appearance of a plus ultra equivalent: più oltre. Martin Behaim's globe of 1492 has a legend at the straits explaining that Hercules set up columns here to mark the limit of his journey.10 5 Now when Dante encounters Odysseus he learns that after a short time at home in Ithaca the longing to experience the world drove the Greek hero back to the sea. He and his companions disregarded the warning at the Straits of Hercules and sailed further west into a world without people (di retro al sol, del mondo sanza gente, 26.117), for unlike beasts men exist “to pursue virtue and knowledge” (per seguir virtute e canoscenza, 26.120). After five days they came in sight of land, but just then a whirlwind overturned the ship and killed the explorers. Surely Charles's Italian advisor Luigi Marliano had this spirit of intrepid adventure (though a more successful one) in mind when he crafted his new device.11 And although contemporaries did not draw the explicit connection between the device and the expansion of the Spanish empire into the New World until the time of Gómara toward the end of Charles's reign, the device's westward orientation must reflect the interest and even excitement of educated and informed people in European courts early in the century.12 II Geography Following the dedication to Charles V with which I began, Gómara continues his General History of the Indies with an extended defence of the new model of a world in which people can indeed sail from the northern temperate zone through the equatorial torrid zone to the southern temperate zone and from Europe to the antipode on the far side of the world. Though one must keep an eye out for Amazons and various monsters such as headless humanoids in the underside of the world,13 in fact people go about with their feet on the ground and their heads in the air. Gómara first published his enormously popular description of the New World and its discovery and conquest in Seville in 1552, sixty years after Columbus's first voyage and long after one would expect the reports of countless Spaniards who had traveled there as well as the evidence of the people, plants, and animals they brought back to have negated any need to validate the reality of the new world. If nothing else, the treasure in gold and silver flowing into Europe’s economy should have triumphed over ancient and medieval geography. But in the middle of the sixteenth century we stand yet at the threshold of the scientific revolution, and contemporaries could not ignore the weight of tradition and ancient authority.14 Although Columbus believed to the end of his life in 1506 that he had traveled four times to the eastern limits of Asia, geographers generally understood by around 1500 that in fact he and the other explorers in the 1490s had encountered a new landmass between Europe and Asia. As Europeans came to terms with the new discoveries, they tried to reconcile them with ancient reports of European contacts with distant lands to the west. Gómara reports that as Columbus progressed triumphantly from 6 the harbor at Palos to the court at Barcelona people debated whether he had reprised Carthaginian navigations or the storm-tossed travels beyond Atlantis reported by Plato in the Critias, or whether he had fulfilled the prophecy of Seneca in his play Medea that a time would come when Thule— antiquity's western-most point—would no longer constitute the limit of the known world.15 Venient annis saecula seris, A time will come at the end of ages quibus Oceanus vincula rerum when Ocean will loosen the chains of things, laxet et ingens pateat tellus and the vast earth will lie open. Tethysque novos detegat orbes Tethys will disclose new worlds, nec sit terris ultima Thule. and Thule will no longer be the end of the earth. (Seneca Medea 375-79) Columbus believed he had realized this prophecy. He accepted a subtle emendation of Tethysque to Tiphysque so that not the ocean personified by the sea-goddess Thethys but the Argonauts' navigator Tiphys, with whom Columbus identifies himself, discovers the new orbs.16 The prophecy of the Cordoban Seneca supported perfectly not only Columbus's personal prophetic vision but also the ideology of Spanish imperialism. Early chroniclers of the discoveries such as Las Casas open their accounts with an evocation of Seneca, and Gómara concludes his the same way (ch 219). Only José de Acosta in his de natura novi orbis of 1588 puts the passage in its context within the play: not a prophecy of a glorious new age of discovery but a pessimistic anticipation of a fallen world.17 The Romans developed an ideology of universal empire, and empire without limits: imperium sine fine.18 At the same time, the theory of mutually incommunicable zones paradoxically limited universal conquest to only a small part of the entire globe, as Cicero showed in his Dream of Scipio. During a visit to Africa in 148 BCE, Scipio Aemelianus has a dream in which his grandfather, Scipio Africanus, the hero of the Second Punic War, anticipates his grandson's widespread conquests throughout the Mediterranean world. Africanus and his son Paulus, Scipio's father, offer the sleeper a vision of the cosmos in which the earth appears minute, and the Roman Empire almost invisible: 8] already the earth itself appeared to me so small, that it grieved me to think of our empire, with which we cover but a point, as it were, of its surface. . . . [12] You see that on the earth only scattered and narrow plots are inhabited; while even in the very patches, as it were, in which men dwell, vast deserts are interspersed; and among those who live on the earth, there are not only such breaks that no communication can pass from one set to another, but some live in opposite zones; some on opposite sides of a zone; some even at the opposite point of the earth to you; and from these, at any rate, you can expect no glory. 7 [13] Moreover you see that this earth is girdled and surrounded by certain belts, as it were; of which two, the most remote from each other, and which rest upon the poles of the heaven at either end, have become rigid with frost; while that one in the middle, which is also the largest, is scorched by the burning heat of the sun. Two are habitable; of these, that one in the South—men standing in which have their feet planted right opposite to yours—has no connection with your race: moreover this other, in the Northern hemisphere which you inhabit, see in how small a measure it concerns you! For all the earth, which you inhabit, being narrow in the direction of the poles, broader East and West, is a kind of little island surrounded by the waters of that sea, which you on earth call the Atlantic, the Great Sea, the Ocean; and yet though it has such a grand name, see how small it really is!19 Scipio's lesson concerns the fleeting insignificance of fame and the true, universal, and eternal value of virtue, but incidentally he receives instruction in Aristotelian geography, which would seem at odds with universal empire. This limitation Seneca's vision in Medea shatters, although in the context of a pessimistic reflection on the declining ages of man. For already people travel effortlessly throughout the inhabited world, and eventually they will go even beyond. But now in the sixteenth century it became possible to disregard the prohibition ne plus ultra, and indeed to go plus ultra, “further beyond.” And it became necessary to understand, explain, and justify the project. III The Imperial Ideal One of the principal issues in the historiography on Charles V concerns his or his advisors’ imperial ideal.20 We can take as our point of departure the facts first that we cannot distinguish his from his advisors’ ideal and second that he and his various advisors had no single ideal but instead a mixture of ideals that changed as they worked themselves out over a long period of time throughout his vast and inhomogeneous realms. For example, Charles’s dynastic mission to enhance Habsburg power figures prominently (bella gerunt alii, tū fēlīx Austria nūbēs). His position as emperor of the revived Roman Empire entailed the practical assumption of territorial, administrative, and jurisdictional unity. He also inherited the more recent tradition of Christian crusading associated not only with the Crusades to the Holy Land but more particularly with the Spanish Reconquista, which culminated in Ferdinand and Isabella's conquest of the Moorish kingdom of Granada in 1492. How did the sudden appearance of a vast new western horizon affect these ideas about empire? Following his election as emperor in 1519 Charles held the ideological position of caput totius christianitatis, the head of all Christendom, derived from the Christian Roman Empire and the 8 Carolingian Empire. That position did not entail political control of the entire Christian world, for princes of the great states such as England, France, and Spain itself had long asserted successfully the principle of rex imperator in regno suo (the king stands as emperor in his own realm). We should therefore speak not of a revived Roman Empire but Roman and Christian universality. The pope constituted its spiritual head, the emperor its temporal head. Such an emperor Europe's other rulers could accept and had long recognized. But the danger that the emperor would reassert political rule persisted, as it had, for example, in the hopeful thinking of Dante in Monarchia (1317) that the emperor could impose peace and unity in fragmented northern Italy. Dante's monarchia mundi, world monarchy, extends without geographical limit to encompass all humanity.21 The justification for universal empire or world monarchy could not depend on imperial conquest, for except for his New World dominions most of Charles’s realms came to him by inheritance.22 The theoretical grounding of universal empire lay elsewhere, in its Christian character. Christians interpreted Augustus's universal Roman Empire as a culmination of the ages: God chose that moment to come into the world when a ruler could truly conduct a census of the whole world, which he ruled in peace and unity. Likewise, as Gómara said, God now chose Charles to restore the unity of the Christian world. One might think that the astonishing new discoveries would enhance this prophetic interpretation, but in fact for the most part it remained restricted to the medieval three-continent geography. For example, Charles's most important officer in the 1520s, Mercurino Gattinara, offered many arguments privately to Charles and publically to Charles's subjects to justify the empire, but he never discussed the New World as part of it. In a memorial of 1523 to Charles he did advocate the extension of the Catholic faith to the Indies.23 But Gattinara typically directed his concern to the practice of government; thus he supported Las Casas’s American Project in 1519-20 and Cortés in his dispute with Velázquez in 1522, and he also set up the Council of the Indies about 1519, all in order to regularize imperial revenue and jurisdiction. In Gattinara’s technocratic world, universal monarchy constituted an administrative problem.24 Gattinara's associate, the Spanish jurist Miguel de Ulzurrun developed an argument for universal monarchy grounded in the law of nations: one monarch must rule in order to secure peace and good communities so that people may live happily, even infidels; any who resist the monarch show themselves as rebels who deserve conquest. But all of Ulzurrun's examples come from the Old World.25 At any rate, when Charles himself spoke of his imperial power he vigorously denied any motivation of aggrandisement and used the argument from Christian universality developed by his principal Spanish councillors Antonio de Guevara and Alfonso de Valdés: the head of Christendom 9 must recognize that in the world other princes will oppose him, so he has direct political control only over his own realms, but as the greatest of the world's rulers he has a unique obligation to reform the church, correct heresy, and combat the infidel universally.26 These ideas appeared in Charles's address to the Royal Council and the Council of State as he explained his plan to leave Spain for Italy in 1528 in order to have the pope crown him emperor. “I want to go to Italy,” Charles said, “in order to work with the pope to ensure that he hold a general council in Italy or in Germany in order to eradicate the heresies and reform the church.”27 In April 1536, when he visited the pope in Rome on the eve of the third war with France, Charles declared before the assembled leaders of the church and ambassadors of Europe’s princes that he had no plan to make war against Christians but only against the infidel; in Europe each should keep his own.28 Whenever anyone accused him of aspiring to political or territorial aggrandizement, Charles responded with outrage.29 When it came to justifying his empire in the Indies, Charles probably found more important than Gattinara’s secular and rational idea of empire the peculiarly Spanish approach to Christian conquest. But to prefer the Spanish position paradoxically separated the new conquests from his Old World realms, for the New World kingdoms comprised an administrative appendage of Castile only. In Barcelona, when he announced his imperial election in 1519, Charles affirmed the integrity of his Spanish kingdoms, which, he insisted, did not and never would become part of the empire.30 In 1520, just before he left for Germany to receive the imperial crown, Charles had his councillor Ruiz de la Mota, Bishop of Badajoz, address the Cortes of Santiago-La Coruña. Mota affirmed the independence of Spain from the empire and its place as the core and most important of all Charles's realms. Charles, he said, will live and die in Spain. God has made Spain great; since Roman times it has sent emperors to Rome: Trajan, Hadrian, Theodosius. “And now the empire has come to Spain to find the emperor, and our King of Spain has become by God's grace King of the Romans and emperor of the world.” He has accepted the onerous burden of rule in order to address the evils of the church and undertake the enterprise against the infidel, and he will employ his royal person in the task. The young Francophone emperor followed Mota with a few words of confirmation in Spanish, which he had begun to learn. Mota mentioned “another new world of gold” as part of Charles's vast empire, but he did not explicitly fit it into any imperial idea or system, which he limits to the Old World.31 If Charles and his advisors neglected the opportunity to see in the New World the culmination of universal monarchy, his subjects eagerly embraced it. At Charles’s accession to the throne of Spain the city of Valladolid wrote to congratulate the young king and encourage him to become señor del mundo and restore Jerusalem to Christendom.32 The conquistadores eagerly transferred this goal to the 10 new world. Thus Cortés in his second letter of 1520 reported (surely falsely) that Moctezuma had transferred his kingdom to the King of Spain, who enjoyed a new realm larger than the German empire.33 The fifth letter of 1526 requests support for further conquests and conversions west from the Pacific coast of Mexico to the Spice Islands.34 I shall conclude with three artistic and literary evocations of Charles's medieval chivalric, divinely ordained, at once Roman imperial, Spanish universalist, and Christian monarchy. For Corpus Cristi, 5 June 1539, in Tlaxcala, the church presented a drama about the conquest of Jerusalem.35 Charles commanded the combined forces of Christianity. The Spaniards led the attack, though divine aid along with the armies of New Spain and the Caribbean played the principal role in securing victory. Figure 5: Plus Oultra Writing Cabinet of Charles V, ca 1530. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. 11 Secondly, let us return to the writing desk made for Charles in Bologna about 1530. 36 Eight busts of Roman emperors from Julius Caesar to Domitian place Charles among the emperors who ensured universal peace and security. A series of biblical scenes from the book of Judges decorate the cabinet: Gideon's struggle with the Midianites. One scene portrays the fleece that God used as a divine sign of his favor for Gideon—thus it evokes the Golden Fleece and recalls Charles devotion to the medieval knightly ideals associated with his favorite order. The scenes remind us as they did Charles of the leader's obligation to defend the religion and combat the infidel. For Midianites read Lutherans and Turks.37 Figure 6: Plus Oultra Writing Cabinet of Charles V, detail, The Angel Appearing to Gideon with the Fleece. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Finally, Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando Furioso, a romance epic set in the time of Charles the Great, includes an episode where the king’s paladin Astolfo, sailing around India on his way to Persia, wonders whether he might circumnavigate the world. His advisor and protector Andronica gives Astolpho a vision of a world surrounded by a vast ocean (15.18), now impenetrable. But, she prophecies, new Argonauts will discover passages across it and around Africa and Asia as they search for new lands (15.19-20). In her vision Andronica sees the imperial flag and the cross: Charles’s armies (15.22). Here she pauses to explain that God decided to permit these discoveries only in Charles's time. It has been God’s will that these two parts of the world be kept apart for six or seven centuries—until 12 there came an emperor with a pious heart, the greatest since Augustus, who could fulfill his plan to reunite the world and start a grand new age when wisdom and justice would rule everywhere for all of mankind’s good.38 Charles will after a long lapse restore justice and virtue. Andronica goes on to describe the conquest of the New World, emphasizing the dual Roman imperial and Christian evangelizing mission, “for there should be / one fold, one shepherd for all humanity” (15.24). Then we learn of Charles's victories in New Spain through his agent Cortés and in Europe and the Mediterranean against the French. This section of the poem does not appear in the original edition of 1516 or the second of 1521. At that time Charles, though King of Spain, had not yet or only recently attained the imperial dignity, nor had the imperial ideology of universal rule encompassing even the far side of the world entered the European imagination. For ten years plus ultra reverberated rather with heroism, chivalry, and Charles’s personal qualities. Then in the period 1529 to 1536 the emperor enjoyed a long period of peace, free of French wars and major Turkish threats.39 Following the sack of Rome in 1527, Italy— long the key to Spanish domination of the Mediterranean—and the pope accepted Charles’s overlordship, and they welcomed him to Bologna for the imperial coronation in February 1530. Now he felt poised to assert Christian universal hegemony: he planned to hold a council, to travel to Germany in order to combat the Lutheran heresy, and to attack Barbarossa’s corsairs in Tunis and Algeria and the Turks in the eastern marches of Germany. Thanks to American gold he could realize some of these projects. The first Peruvian gold arrived in 1534 and helped finance the African campaign of 1535. So by the time of the definitive publication of Orlando Furioso in 1532, universal hegemony had entered the European imagination, and in this poem unusually we find both the European and the Hispanic imperial ideas combined with a geographical interpretation of plus ultra that stretches to the far side of the world. 1 Francisco López de Gómara, General History of the Indies, 1st ed (Zaragoza: Miguel de Zapila, 1552), dedication. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are mine. Pedro Mexía, Historia del emperador Carlos V, ed Juan de Mata Carriazo y Arroquia (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1945), 112, shares the sentiment: “paresce [que aquella tierra] la tenía Dios guardada para el Emperador.” On Gómara’s attempt to reconcile the viciousness of the conquest with imperial aims see Cristián A Roa-de-la-Carrera, Histories of Infamy: Francisco López de Gómara and the Ethics of Spanish Imperialism, trans Scott Sessions (Boulder: Univ of Colorado Press, 2005). 2 Marcel Batillon, “Plus Oultre: La cour découvre le Nouveau Monde,” in Fêtes et cérémonies au temps de Charles Quint, ed. Jean Jacquot (Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1960), 13-27; Earl Rosenthal, “Plus Ultra, Non Plus Ultra, and the Columnar Device of Emperor Charles V,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 34 (1971): 204228; id, “The Invention of the Columnar Device of Emperor Charles V at the Court of Burgundy in Flanders in 1516,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 36 (1973): 198-230. 13 Laurent Vital, “Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagne de 1517 à 1518,” in Collection des voyages des souverains de Pays-Bas, ed Louis P Gachard and Charles Piot, vol 3 (Brussels: Commission Royale d'Histoire, 1881): 57. 4 Vital, “Premier Voyage,” 3: 213; Vital does not quote the Greek version and he glosses Nondum as “qui est à dire non pas encore.” Rosenthal (“Plus Ultra,” 223 n 83) quips, “Charles seems to have admitted that, though his motto was 'still further,' he had 'not yet' gone very far but, then, 'who could say' how far he would go?” 5 Rosenthal, “Plus Ultra,” 223 and pl 38c. 6 Ibid, 223-24 and pl 38b; Rafael Domínguez Casas, “Arte y simbología en el capítulo barcelonés de la Orden del Toisón de Oro (1519),” (Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2001), http://bib.cervantesvirtual.com/historia/CarlosV/graf/DguezCasas/8_3_dguez_casas_fotosmini.shtml, accessed 11 Apr 2012. 7 Rosenthal, “Plus Ultra,” 217-18, 224. For noch weiter see ibid, 224-25 with pl 40d; for ulterior ibid, 225 with pl 40b. Rosenthal also construes the possible influence of the pilgrim’s slogan Oltrée or Outrée (222). 8 Ángeles Jordano, “The Plus Oultra Writing Cabinet of Charles V: Expression of the Sacred Imperialism of the Austrias,” Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 9 (2011): 14-26, available at DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/jcms.91105, accessed 9 Apr. 2012. 9 Trans Robert Hollander and Jean Hollander, Princeton Dante Project, available at http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/pdp/. Accessed 9 Apr 2012. 10 See Rosenthal, “Plus Ultra,” 210-13, on these texts and the globe. 11 See ibid, 210-13, on the globe and ibid, 218-22, for Renaissance interpretations of this venturesome view of the columns of Hercules. By the early sixteenth century, “the Columns were no longer considered limitary markers but, rather, symbolic points of departure for the venturesome spirits of the day” (221). 12 So Rosenthal, “Plus Ultra,” 227. 13 Kathleen N March and Kristina M Passman, “The Amazon Myth and Latin America,” in The Classical Tradition and the Americas, vol 1: European Images of the Americas and the Classical Tradition, ed Wolfgang Haase and Meyer Reinhold (Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1994), 284-338. 14 W G I Randles, “Classical Models of World Geography and Their Transformation Following the Discovery of America,” in The Classical Tradition and the Americas, 5-76. Kathleen A Myers, “Imitation, Authority, and Revision in Fernández de Oviedo’s Historia general y natural de las Indias,” Romance Languages Annual 3 (1991): 523-30. 15 Gómara ch 17. On the Columbian and post-Columbian reception of the Senecan prophecy see James Romm, “New World and 'novus orbes': Seneca in the Renaissance Debate over Ancient Knowledge of the Americas,” in Classical Tradition and the Americas, 77-116, who also points out (78 n 2) that Gómara anachronises this debate, which Romm cannot otherwise find attested before 1527. Romm lists the available classical reports of contact with western lands at 79 nn 5-8, and Gabriella Moretti offers an exhaustive survey: “The Other World and the 'Antipodes': The Myth of the Unknown Countries between Antiquity and the Renaissance,” in The Classical Tradition and the Americas, 241-84. 16 Romm, “New World and 'novus orbes,'” 81-85, discusses Columbus's prophetic take on the Senecan passage in his Libro de las Profecías. He goes on to point out (101-112) that until the turn of the seventeenth century scholars had to take seriously ancient accounts seemingly relevant to the discoveries; that they had their geography so wrong either puzzled Renaissance scholars or demonstrated the limitations of divine revelation among the pagans. On interpretations of the Medea passage cf Sabine MacCormack, On the Wings of Time: Rome, the Incas, Spain, and Peru (Princeton: Princeton Univ Press, 2007), 248-49. For the text see Cristobol Colón, Libro de las profecías, intr, trans, and notes by Kay Brigham (Barcelona: Libros CLIE; Fort Lauderdale: TSELF, 1992). See also the discussion of Moretti, “The Other World and the 'Antipodes,'” 275-82. 17 Romm, “New World and 'novos orbes,'” 96, 112-13; Bartolomé de Las Casas, Historia de las Indias, ed Agustín Millares Carlo and Lewis Hanke, 3 vols, 2d ed (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1965), 1.10. Gómara, Historia general de las Indias, ch 219. 18 Lucan 10.48-51: Licet usque sub Arcton / Regnemus, Zephyrique domos terrasque premamus /50 Flagrantis post terga Noti: cedemus in ortus / Arsacidum domino. Ver Aen 1.278-79: His ego nec metas rerum nec tempora pono; / imperium sine fine dedi (of the Romans); 1.287: imperium oceano, famam qui terminet astris (of Augustus). In particular see Moretti, “The Other World and the 'Antipodes,'” 257-62; in general see Claude Nicolet, L'inventaire du monde: Géographie et politique aux origines de l'Empire romain (Paris: Fayard, 1988). 19 6.16, 20-21; Cicero, The Dream of Scipio—Somnium Scipionis, trans W. D. Pearman (1883), available at http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/cicero_dream_of_scipio_02_trans.htm, accessed 21 March 2012. Boethius echoes the sentiment: Cons 2.7. 20 Hans-Joachim König, “Plus Ultra: ¿Emblema de conquisto e imperio universal? América y Europa en el pensamiento político de la España de Carlos V,” in Carlos V / Karl V. 1500-2000, ed Alfred Kohler (Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Conmemoración de los Centenarios de Felipe II y Carlos V, 2001), 577-99. Ramón Menéndez Pidal, “Formación del fundamental pensamiento político de Carlos V,” in Charles-Quint et son temps (Paris: Éditions du Centre National de la 3 14 Recherche Scientifique, 1959), 1-8, a shorter version of the synonymous article in Karl V.: Der Kaiser und Seine Zeit, ed Peter Rassow and Fritz Schalk (Köln: Böhlau, 1960), both distillations of Idea imperial de Carlos V (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1940). J Vicens Vives, “Imperio y administración en tiempo de Carlo V,” in Charles-Quint et son temps, 9-21. Frances A Yates, “Charles Quint et l'idée d'empire,” in Fêtes et cérémonies au temps de Charles Quint, ed. Jean Jacquot (Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1960), 57-97. Alfred Kohler reviews the principle theories in Neue deutsche Biographie 11 (Munich: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1977), 191-211 sv “Karl V. 1500-1558,“ at 182-93; and id, Quellen zur Geschichte Karls V. (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1990), 11-16. König, “Plus Ultra,” offers the only study of Charles's imperial idea that concerns itself with the New World extension. 21 König, “Plus Ultra,” 581-82; Yates, “Charles-Quint,” 59-69. 22 Karl Brandi, Kaiser Karl V. : Werden und Schicksal einer Persönlichkeit und eines Weltreiches, 8th ed (Munich: SocietätsVerlag, 1986), 110. 23 König, “Plus Ultra,” 582-85 24 John M Headley, The Emperor and His Chancellor: A Study of the Imperial Chancellery under Gattinara (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 11-12, notes that Gattinara supplemented other arguments in support of Charles's imperial power with the effective power of centralizing institutions; Luigi Avonto, Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara e l’America (Vercelli: Società storica vercellese, 1981), shows how Gattinara treated the New World as an administrative problem. 25 Catholicum opus imperiale regiminis mundi (1525), discussed by König, “Plus Ultra,” 586-88. 26 Valdés, Diálogo de Mercurio y Carón (1528); Guevara, Libro Áureo del Emperador Marco Aurelio (1528); discussed by König, “Plus Ultra,” 588-91. 27 Alonso de Santa Cruz, Crónica del Emperador Carlos V, ed Ricardo Beltrán y Róspide y Antonio Blázquez y Delgado Alguilera, 5 vols (Madrid: Imprenta del Patronato de huérfanos de intendencia é intervención militares, 1920-1925), 3.45458. R Menéndez Pidal argued that Guevara wrote this speech for Charles: “Antonio de Guevara y la idea imperial de Carlos V,” Archivo Ibero-Americano 6 (1946): 131-38. 28 A Morel-Fatio, “L’espagnol langue universelle,” Bulletin hispanique 15 (1913): 207-225, at 212-15. Prudencio de Sandoval, Historia de la vida y hechos del emperador Carlos V, ed Carlos Seco Serrano (Madrid, Atlas, 1955-56), 23.5, Santa Cruz Crónica, 5.19. 29 Eg, Contarini’s report in Eugenio Alberi, Relazioni degli ambasciatori veneti, 1.3 (Florence: Tipograpfia e Calcografia all’insegna di Clio, 1840), 178 = Louis Prosper Gachard, Relations des ambassadeurs vénitiens sur Charles-Quint et Philippe II, 2 (Brussels: M Hayez, 1855): XV-XVI. 30 Santa Cruz, Crónica, 1.205-6. 31 Cortes de los antiguos reinos de León y de Castilla, 4 (Madrid: Real Academia de Historia, 1882): 293-98. 32 Sandoval, Historia de Carlos V, 1.61. 33 Hernán Cortés, Letters from Mexico, trans and ed Anthony Pagden (New Haven and London: Yale Univ Press, 1986), 99 with 467-69 n 42. 34 Cortés, Letters, 444-45. 35 Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, Memoriales o, Libro de las cosas de Nueva España y de los naturales de ella, ed Edmundo O'Gorman (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1971), 411; described and analyzed by Carmen Corona, “El auto La conquista de Jerusalén: Hernán Cortés y la transgresión de la figura,” in El escritor y la escena III: Estudios en honor de Francisco Ruiz Ramón, ed Ysla Campbell (Juárez: Universidad Autónoma, 1997), 79-87. 36 Ángeles Jordano, “The Plus Oultra Writing Cabinet.” 37 Jordano, “The Plus Oultra Writing Cabinet.” 38 Ludovico Ariosto, Orlando Furioso: A New Verse Translation, trans David R Slavitt (Cambridge: Harvard Univ Press, 2009), 15.23. 39 Batillon, “Plus Ultra,” 23-24. Bibliography Alberi, Eugenio. Relazioni degli ambasciatori veneti. 1.3. Florence: Tipograpfia e Calcografia all’insegna di Clio, 1840. Ariosto, Ludovico. Orlando Furioso: A New Verse Translation. Trans David R Slavitt. Cambridge: Harvard Univ Press, 2009. 15 Avonto, Luigi. Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara e l’America. Vercelli: Società storica vercellese, 1981. Batillon, Marcel. “Plus Oultre: La cour découvre le Nouveau Monda.” In Fêtes et cérémonies au temps de Charles Quint, ed. Jean Jacquot, 13-27. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1960. Brandi, Karl. Kaiser Karl V. : Werden und Schicksal einer Persönlichkeit und eines Weltreiches. 8th ed. Munich: Societäts-Verlag, 1986. Cicero. The Dream of Scipio—Somnium Scipionis. Trans W. D. Pearman (1883). Available at http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/cicero_dream_of_scipio_02_trans.htm. Accessed 21 March 2012. Colón, Cristobol. Libro de las profecías. Intr, trans, and notes by Kay Brigham. Barcelona: Libros CLIE; Fort Lauderdale: TSELF, 1992. Corona, Carmen. “El auto La conquista de Jerusalén: Hernán Cortés y la transgresión de la figura.” In El escritor y la escena III: Estudios en honor de Francisco Ruiz Ramón , ed Ysla Campbell, 79-87. Juárez: Universidad Autónoma, 1997. Cortés, Hernán. Letters from Mexico. Trans and ed Anthony Pagden. New Haven and London: Yale Univ Press, 1986. Cortes de los antiguos reinos de León y de Castilla. Vol 4. Madrid: Real Academia de Historia, 1882. Dante. Inferno. Trans Robert Hollander and Jean Hollander. Princeton Dante Project. Available at http://etcweb.princeton.edu/dante/pdp/. Accessed 9 Apr 2012. Domínguez Casas, Rafael. “Arte y simbología en el capítulo barcelonés de la Orden del Toisón de Oro (1519).” Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2001. Available at http://bib.cervantesvirtual.com/historia/CarlosV/graf/DguezCasas/8_3_dguez_casas_fotosmi ni.shtml. Accessed 11 Apr 2012. Gachard, Louis Prosper. Relations des ambassadeurs vénitiens sur Charles-Quint et Philippe II. Vol 2. Brussels: M Hayez, 1855. Headley, John M. The Emperor and His Chancellor: A Study of the Imperial Chancellery under Gattinara. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. Jordano, Ángeles. “The Plus Oultra Writing Cabinet of Charles V: Expression of the Sacred Imperialism of the Austrias.” Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies 9 (2011): 14-26. Available at DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/jcms.91105. Accessed: 9 Apr 2012. Kohler, Alfred. Neue deutsche Biographie 11 (Munich: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1977): 191-211 sv “Karl V. 1500-1558.“ ________. Quellen zur Geschichte Karls V. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1990. König, Hans-Joachim. “Plus Ultra: ¿Emblema de conquisto e imperio universal? América y Europa en el pensamiento político de la España de Carlos V.” In Carlos V / Karl V. 1500-2000, ed Alfred Kohler, 577-99. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal para la Conmemoración de los Centenarios de Felipe II y Carlos V, 2001. Las Casas, Bartolomé de. Historia de las Indias. Ed Agustín Millares Carlo and Lewis Hanke. 3 vols. 2d ed. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1965. 16 López de Gómara, Francisco. General History of the Indies. 1st ed. Zaragoza: Miguel de Zapila, 1552. MacCormack, Sabine. On the Wings of Time: Rome, the Incas, Spain, and Peru. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press, 2007. March, Kathleen N, and Kristina M Passman. “The Amazon Myth and Latin America.” In The Classical Tradition and the Americas. Vol 1: European Images of the Americas and the Classical Tradition, ed Wolfgang Haase and Meyer Reinhold, 284-338. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1994. Menéndez Pidal, Ramón. Idea imperial de Carlos V. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1940. ________. “Antonio de Guevara y la idea imperial de Carlos V.” Archivo Ibero-Americano 6 (1946): 131-38. ________. “Formación del fundamental pensamiento político de Carlos V.” In Charles-Quint et son temps, 1-8. Paris: Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1959. ________. “Formación del fundamental pensamiento político de Carlos V.” In Karl V.: Der Kaiser und Seine Zeit, ed Peter Rassow and Fritz Schalk. Köln: Böhlau, 1960. Mexía, Pedro. Historia del emperador Carlos V. Ed Juan de Mata Carriazo y Arroquia. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1945. Morel-Fatio, A. “L’espagnol langue universelle.” Bulletin hispanique 15 (1913): 207-225. Moretti, Gabriella. “The Other World and the 'Antipodes': The Myth of the Unknown Countries between Antiquity and the Renaissance.” In The Classical Tradition and the Americas. Vol 1: European Images of the Americas and the Classical Tradition, ed Wolfgang Haase and Meyer Reinhold, 241-84. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1994. Myers, Kathleen A. “Imitation, Authority, and Revision in Fernández de Oviedo’s Historia general y natural de las Indias.” Romance Languages Annual 3 (1991): 523-30. Nicolet, Claude. L'inventaire du monde: Géographie et politique aux origines de l'Empire romain. Paris: Fayard, 1988. Randles, W G I. “Classical Models of World Geography and Their Transformation Following the Discovery of America.” In The Classical Tradition and the Americas. Vol 1: European Images of the Americas and the Classical Tradition, ed Wolfgang Haase and Meyer Reinhold, 5-76. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1994. Roa-de-la-Carrera, Cristián A. Histories of Infamy: Francisco López de Gómara and the Ethics of Spanish Imperialism. Trans Scott Sessions. Boulder: Univ of Colorado Press, 2005. Romm, James. “New World and 'novus orbes': Seneca in the Renaissance Debate over Ancient Knowledge of the Americas.” In Classical Tradition and the Americas, Vol 1: European Images of the Americas and the Classical Tradition, ed Wolfgang Haase and Meyer Reinhold, 77-116. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1994. Rosenthal, Earl. “Plus Ultra, Non Plus Ultra, and the Columnar Device of Emperor Charles V.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 34 (1971): 204-228. ________. “The Invention of the Columnar Device of Emperor Charles V at the Court of Burgundy in Flanders in 1516.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 36 (1973): 198-230. Sandoval, Prudencio de. Historia de la vida y hechos del emperador Carlos V. Ed Carlos Seco 17 Serrano. Madrid, Atlas, 1955-56. Santa Cruz, Alonso de. Crónica del Emperador Carlos V. Ed Ricardo Beltrán y Róspide y Antonio Blázquez y Delgado Alguilera. 5 vols. Madrid: Imprenta del Patronato de huérfanos de intendencia é intervención militares, 1920-1925. Toribio de Benavente Motolinia. Memoriales o, Libro de las cosas de Nueva España y de los naturales de ella. Ed Edmundo O'Gorman. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1971. Vicens Vives, J. “Imperio y administración en tiempo de Carlo V.” In Charles-Quint et son temps, 9-21. Paris: Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1959. Vital, Laurent. “Premier Voyage de Charles-Quint en Espagna de 1517 a 1518.” In Collection des voyages des souverains de Pays-Bas. Ed Louis P Gachard and Charles Piot. Vol 3. Brussels: Commission Royale d'Histoire, 1881. Yates, Frances A. “Charles Quint et l'idée d'empire.” In Fêtes et cérémonies au temps de Charles Quint, ed. Jean Jacquot, 57-97. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1960. 18