Monopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, And Strategic Pricing

advertisement

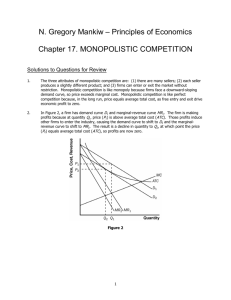

Monopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, and Strategic Pricing Chapter 13 Introduction • In discussing real-world competition, the focus quickly becomes market structure. • Market structure is the physical characteristics of the market within which firms interact. Introduction • Market structure involves the number of firms in the market and the barriers to entry. • Perfect competition, with an infinite number of firms, and monopoly, with a single firm, are polar opposites. Introduction • Monopolistic competition and oligopoly lie between these two extremes. – Monopolistic competition is a market structure in which there are many firms selling differentiated products. – Oligopoly is a market structure in which there are a few interdependent firms. Introduction • Most U.S. industry structures fall almost entirely between monopolistic competition and oligopoly. • Perfectly competitive and monopolistic industries are nearly nonexistent. Problems Determining Market Structure • Defining a market has problems: – What is an industry and what is its geographic market -- local, national, or international? – What products are to be included in the definition of an industry? Classifying Industries • One of the ways in which economists classify markets is by cross-price elasticities. – Cross-price elasticity measures the responsiveness of the change in demand for a good to change in the price of a related good. Classifying Industries • Industries are classified by government using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). – The North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) is a classification system of industries adopted by Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. in 1997. Classifying Industries • When economists talk about industry structure the general practice is to refer to three-digit industries. – Under the NAICS, a two-digit industry is a broadly based industry. – A three-digit industry is a specific type of industry within a broadly defined twodigit industry. Two- and Four- Digit Industry Groups Three-Digit Subsectors Two-Digit Sectors 44-45 Retail trade 48-49 Transportation and warehousing 513 Broadcasting and 51 Information telecommunications 52 Finance and Insurance Determining Industry Structure • Economists use one of two methods to measure industry structure: 1. The Concentration Ratio 2. The Herfindahl Index Concentration Ratio • The concentration ratio is the percentage of industry output that a specific number of the largest firms have. Concentration Ratio • The most commonly used concentration ratio is the four-firm concentration ratio. • The higher the ratio, the closer to an oligopolistic or monopolistic type of market structure. The Herfindahl Index • The Herfindahl index is an alternative method used by economists to classify the competitiveness of an industry. • It is calculated by adding the squared value of the market shares of all firms in the industry. The Herfindahl Index • Two advantages of the Herfindahl index is that it takes into account all firms in an industry as well as giving extra weight to a single firm that has an especially large market share. The Herfindahl Index • The Herfindahl Index is important because it is used as a marker by the Justice Department for allowing or disallowing mergers to take place. – If the index is less than 1,000, the industry is considered competitive thus allowing the merger to take place. Concentration Ratios and the Herfindahl Index Industry Meat packing Book publishing Greeting card publishing Soap and detergent Men’s footwear Computing equipment Burial caskets Four-firm Herfindahl concentration index ratio 29 17 84 60 28 43 52 325 190 2,840 1,306 378 793 1,247 Conglomerate Firms and Bigness • Neither the four-firm concentration ratio or the Herfindahl index gives a complete picture of corporations’ size. Conglomerate Firms and Bigness • This is because many firms are conglomerates—huge corporations whose activities span various unrelated industries. The Importance of Classifying Industry Structure • Classifying industry structure is important because structure affects firm behavior. – The greater the number of sellers, the more the likelihood the industry is competitive. The Importance of Classifying Industry Structure • The number of firms in an industry plays a role in determining whether firms explicitly take other firms’ actions into account. • Oligopolies take into account the reactions of other firms; monopolistic competitors do not. The Importance of Classifying Industry Structure • In monopolistic competition, the large number of firms makes it unlikely that an individual firm will explicitly take into account rival firms’ responses to their decisions. The Importance of Classifying Industry Structure • In oligopoly, with fewer firms, each firm explicitly engages in strategic decision making. • Strategic decision making – taking explicit account of a rival’s expected response to a decision you are making. Monopolistic Competition • The four distinguishing characteristics of monopolistic competition are: – – – – Many sellers. Differentiated products. Multiple dimensions of competition. Easy entry of new firms in the long run. Many Sellers • When there are many sellers as in monopolistic competition, they do not take into account rivals’ reactions. • The existence of many sellers also makes collusion difficult. • Monopolistically competitive firms act independently. Differentiated Products • The “many sellers” characteristic gives monopolistic competition its competitive aspect. • Product differentiation gives monopolistic competition its monopolistic aspect. Differentiated Products • Differentiation exists so long as advertising convinces buyers that it exists. • Firms will continue to advertise as long as the marginal benefits of advertising exceed its marginal costs. Multiple Dimensions of Competition • One dimension of competition is product differentiation. • Another is competing on perceived quality. • Competitive advertising is another. • Others include service and distribution outlets. Easy Entry of New Firms in the Long Run • There are no significant barriers to entry. • Barriers to entry prevent competitive pressures. • Ease of entry limits long-run profit. Output, Price, and Profit of a Monopolistic Competitor • A monopolistically competitive firm prices in the same manner as a monopolist— where MC = MR. • But the monopolistic competitor is not only a monopolist but a competitor as well. Output, Price, and Profit of a Monopolistic Competitor • At equilibrium, ATC equals price and economic profits are zero. • This occurs at the point of tangency of the ATC and demand curve at the output chosen by the firm. Monopolistic Competition Price MC ATC PM MR 0 QM D Quantity Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Perfect Competition • Both the monopolistic competitor and the perfect competitor make zero economic profit in the long run. Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Perfect Competition • The perfect competitors demand curve is perfectly elastic. • Easy entry, zero economic profits, and a uniform product means that the perfect competitor produces at the minimum of the ATC curve. Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Perfect Competition • A monopolistic competitor faces a downward sloping demand curve, and produces where MC = MR. • The ATC curve is tangent to the demand curve at that level, which is not at the minimum point of the ATC curve. Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Perfect Competition • Increasing market share is a relevant concern for a monopolistic competitor but not for a perfect competitor. Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Perfect Competition • In the real world of monopolistic competition, increasing output and market share lowers average total cost. Comparing Perfect and Monopolistic Competition Perfect competition Price Price MC ATC D PC 0 Monopolistic competition QC Quantity MC ATC PM PC 0 QM MR D QC Quantity Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Monopoly • The difference between a monopolist and a monopolistic competitor is in the position of the average total cost curve in long-run equilibrium. Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Monopoly • For a monopolist, the average total cost curve can be, but need not be, at a position below price so that the monopolist makes a long-run economic profit. Comparing Monopolistic Competition with Monopoly • For a monopolistic competitor, the average total cost curve is tangent to the demand curve at the price and output chose by the monopolistic competitor so that there are zero economic profits in the long run. Advertising and Monopolistic Competition • Firms in a perfectly competitive market have no incentive to advertise: they can sell all they produce at the market price. • Monopolistic competitors have a strong incentive to do so. Advertising and Monopolistic Competition • The primary goals of the advertiser is to 1. move the demand curve to the right and 2. make it more inelastic. Advertising and Monopolistic Competition • Advertising shifts the demand curve shifts out and shifts the ATC curve up. • That way the firm can sell more, charge more, or both. Advertising & the Creation of Name Brands • There is a sense of trust in buying brands we know. • Advertising creates Name Brand Recognition. • Consumers are sometimes willing to pay more to reduce their uncertainty about the quality of the product. • Companies that develop name brands can often charge more than for “no name” homogeneous products. Oligopoly • Oligopoly is a market structure where there are a small number of mutually interdependent firms. • Each firm must take into account the expected reaction of other firms to its profit maximizing output decision. Models of Oligopoly Behavior • No single general model of oligopoly behavior exists. • Two models of oligopoly behavior are the cartel model and the contestable market model. Models of Oligopoly Behavior • In the cartel model, the firms in the industry (oligopolies) collude to set a monopoly price. • In the contestable market model, an oligopolistic firm with no barriers to entry sets a competitive price. The Cartel Model • A cartel (sometimes called a trust) is a combination of firms that acts as it were a single firm. • A cartel is a shared monopoly. The Cartel Model • If oligopolies can limit the entry of other firms and form a cartel, they can increase the profits going to the combination of firms in the cartel. The Cartel Model • The model assumes that oligopolies act as if they were monopolists that have assigned output quotas to individual member firms so that total output is consistent with joint profit maximization. Implicit Price Collusion • Formal collusion is illegal in the U.S. while informal collusion is permitted. • Implicit price collusion exists when multiple firms make the same pricing decisions even though they have not consulted with one another. Implicit Price Collusion • Sometimes the largest or most dominant firm takes the lead in setting prices and the others follow. Cartels and Technological Change • Cartels can be destroyed by an outsider with technological superiority. • Thus, cartels with high profits will provide incentives for significant technological change. Why Are Prices Sticky? • Informal collusion is an important reason why prices are sticky. • Another is the kinked demand curve. Why Are Prices Sticky? • When there is a kink in the demand curve, there has to be a gap in the marginal revenue curve. • The kinked demand curve is not a theory of oligopoly but a theory of sticky prices. The Kinked Demand Curve Price a P b MC0 c D1 MC1 d MR1 D2 0 Q MR2 Quantity The Contestable Market Model • According to the contestable market model, barriers to entry and barriers to exit determine a firm’s price and output decisions. – Even if the industry contains only one firm, it could still be a competitive market if entry is open. The Contestable Market Model • The stronger the ability of the oligopolists to collude and prevent market entry, the closer it is to a monopolistic situation. • The weaker the ability to collude is, the more competitive it is. Strategic Pricing and Oligopoly • Both the cartel and contestable market models use strategic pricing decisions— they set their prices based on the expected reactions of other firms. Strategic Pricing and Oligopoly • Cartelization strategy is limited by entry of new firms because the newcomer may not want to cooperate with the other firms. Price Wars • Price wars are the result of strategic pricing decisions gone wild. • Sometimes a firm engages in this activity because it hates its competitor. Price Wars • A firm may develop a predatory pricing strategy as a matter of policy – A predatory pricing strategy involves temporarily pushing the price down in order to drive a competitor out of business. Game Theory and Strategic Decision Making • Most oligopolistic strategic decision making is carried out with explicit or implicit use of game theory. • Game theory is the application of economic principles to interdependent situations. The Prisoner’s Dilemma and a Duopoly Example • The prisoner's dilemma can be used to illustrate the behavior of a duopoly. • The prisoner’s dilemma is one well-known game that demonstrates the difficulty of cooperative behavior in certain circumstances. The Prisoner’s Dilemma and a Duopoly Example • The prisoners dilemma has its simplest application when the oligopoly consists of only two firms—a duopoly. The Prisoner’s Dilemma and a Duopoly Example • By analyzing the strategies of both firms under all situations, all possibilities are placed in a payoff matrix. • A payoff matrix is a box that contains the outcomes of a strategic game under various circumstances. Firm and Industry Duopoly Cooperative Equilibrium MC ATC $800 700 700 600 600 500 500 Price 575 Price $800 400 300 D 100 100 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Quantity (in thousands) (a) Firm's cost curves Competitive solution 300 200 1 MC 400 200 0 Monopolist solution 0 MR 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Quantity (in thousands) (b) Industry: Competitive and monopolist solution Firm and Industry Duopoly Equilibrium When One Firm Cheats $900 $800 $800 800 700 700 700 600 550 500 600 550 500 600 550 500 400 300 A 400 Price A Price Price MC ATC MC ATC 300 200 200 100 100 100 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Quantity (in thousands) (a) Noncheating firm’s loss 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Quantity (in thousands) (b) Cheating firm’s profit B A NonCheating 400 cheating firm’s firm’s output 300 output 200 0 C 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Quantity (in thousands) (c) Cheating solution Duopoly and a Payoff Matrix • The duopoly is a variation of the prisoner's dilemma game. • The results can be presented in a payoff matrix that captures the essence of the prisoner's dilemma. The Payoff Matrix of Strategic Pricing Duopoly A Does not cheat A Cheats A +$200,000 A $75,000 B Does not cheat B $75,000 B – $75,000 A – $75,000 A0 B Cheats B +$200,000 B0 Oligopoly Models, Structure, and Performance • Oligopoly models are based either on structure or performance. – The four-fold division of markets considered so far are based on market structure. – Structure means the number, size, and interrelationship of firms in the industry. Oligopoly Models, Structure, and Performance • A monopoly is the least competitive, perfectly competitive industries are the most competitive. Oligopoly Models, Structure, and Performance • The contestable market model gives less weight to market structure. – Markets in this model are judged by performance, not structure. – Close relatives of it have previously been called the barriers-to-entry model, the stay-out pricing model, and the limitedpricing model. Oligopoly Models, Structure, and Performance • There is a similarity in the two approaches. – Often barriers to entry are the reason there are only a few firms in an industry. – When there are many firms, that suggests that there are few barriers to entry. – In such situations, which make up the majority of cases, the two approaches come to the same conclusion. Monopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, and Strategic Pricing End of Chapter 13