Congestive Heart Failure

advertisement

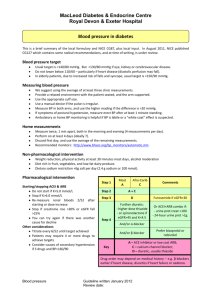

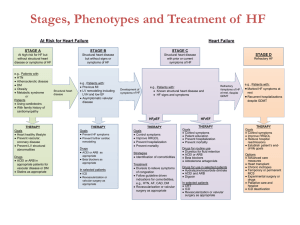

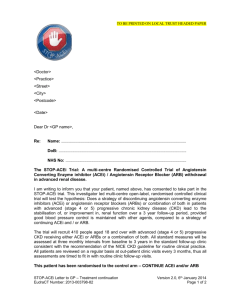

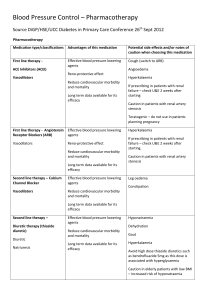

Michelle A. Hart MD CCFP M.Sc.C.H Sid Feldman MD CCFP FCFP Baycrest Health Sciences, Toronto, ON Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto Faculty/Presenter Disclosure • Faculty: Dr. Michelle Hart • Program: 51st Annual Scientific Assembly • Relationships with commercial interests: None Disclosure of Commercial Support • This program has not received financial support. • This program has not received in-kind support. • Potential for conflict(s) of interest: None Mitigating Potential Bias None Faculty/Presenter Disclosure • Faculty: Dr. Sid Feldman • Program: 51st Annual Scientific Assembly • Relationships with commercial interests: None Disclosure of Commercial Support • This program has not received financial support. • This program has not received in-kind support. • Potential for conflict(s) of interest: None Mitigating Potential Bias None Dr. Daphna Grossman 1. 2. 3. 4. By the end of this hour you will be able to: 1. Utilize best methods for accurate diagnosis of congestive heart failure 2. Apply current evidence for effective management of congestive heart failure and delay progression of heart failure 3. Employ resources in the community to support patients with strategies for selfmanagement 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Review on basics of heart failure Diagnosing Heart Failure Management of Heart Failure Future Directions: What’s coming down the pipeline for HF Management Advanced Care Planning, Prognostication and End-Of-Life Summary of Heart Failure Definition of Heart Failure Why is it important? How does it happen? Types of Heart Failure Staging and Classes of Heart Failure Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) “Complex syndrome in which abnormal heart function results in, or increases risk of clinical symptoms and signs of low cardiac output and/or pulmonary or systemic congestion” In North America, it is the fastest growing cardiac diagnosis for individuals > 65 years Average annual mortality rate of 10-35% in Canada Myocardial injury or stress on heart initiates the process of ventricular dysfunction Cardiac remodelling worsens function Progressive process Declining function exacerbates remodelling Neurohormonal activation: hemodynamic stresses, cardiotoxicity, myocardial fibrosis – ongoing remodelling and progression Two Categories: Left ventricular systolic dysfunction with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HF-REF) HF with preserved ejection fraction (HF-PEF) ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ½ the cases More often in older, female patients Often have hypertension, atrial fibrillation Less coronary artery disease Mortality less than for HF-REF Morbidity similar American Heart Association Treatment linked to objective criteria Uses risk factor and cardiac structure New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification Based on subjective clinical evaluation Changes with treatment response and disease progression Complementary with AHA Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) uses NYHA Fatigue Weakness Ankle edema Weight gain Exertional dyspnea Orthopnea Paroxysmal Nocturnal Dyspnea Cough Ascites/Abdominal Distension Enlarged liver Tachycardia Displaced, sustained apex beat 3rd or 4th heart sound Left parasternal heave Murmurs of mitral and/or tricuspid regurgitation Increased JVP Pulmonary crackles Pleural effusion Renal failure Obesity COPD Depression/anxiety Severe anemia Pulmonary embolism Atrial Fibrillation Hypoalbuminemia Dependent edema Fluid retention 2˚ to calcium channel blocker or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Class 1 Recommendation, Level C Evidence Clinical history Physical Exam Initial lab investigations Transthoracic Echocardiography Radionuclide Angiography Coronary Angiography Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Assessment of Functional Capacity: NYHA Figure 1 New York Heart Association Classification Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2013; 29:168-181) Copyright © 2013 Canadian Cardiovascular Society CCS Updated 2012 Guidelines Constellation of symptoms (eg, orthopnea and shortness of breath on exertion) and signs (eg, edema and respiratory crackles) Physical examination evaluates systemic perfusion and presence of congestion (cold or warm, wet or dry) Laboratory testing Electrocardiogram (ECG) Chest x-ray Echocardiogram Taken from: The Radiology Assistant http://www.radiologyassistant.nl/en/p4c132f36513d4 Taken from: The Radiology Assistant http://www.radiologyassistant.nl/en/p4c132f36513d4 PCWP = Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure A slight mild elevation of cardiac troponin is not infrequently observed in acute decompensation and not necessarily indicative of myocardial infarction (MI). The utility of natriuretic peptide (NP) to exclude (“rule out”) or confirm (“rule in”) the diagnosis in the appropriate clinical scenario is well established. NPs are best used when the diagnosis is uncertain BNP and prohormone (NT-proBNP) are synthesized and released from the heart in response to end-diastolic volume and pressure High negative predictive value BNP <100 pg/mL rules out HF in patients presenting with dyspnea in the acute care setting [level I-1 Evidence] BNP > 500 pg/mL confirms HF in patients with dyspnea Several clinical scoring systems have been derived and validated and combine commonly used clinical features with NP values to improve diagnosis and decision-making The most commonly used clinical scoring system was developed by Baggish et al. Table 1. A clinical scoring system for diagnosis of AHF Predictor Possible score Age > 75 y 1 Orthopnea present 2 Lack of cough 1 Current loop diuretic use (before presentation) 1 Rales on lung exam 1 Lack of fever 2 Elevated NT-proBNP 4 Interstitial edema on chest x-ray 2 14 Likelihood of heart failure Low Your patient's score Total = 0-5 Intermediate 6-8 High 9-14 Elevated NT-proBNP was defined as > 450 pg/mL if age < 50 years and > 900 pg/mL if age > 50 years Source: CCS Guidelines 2012 Age Sex Weight Medications Pulmonary Disease Renal disease Routine use of BNP in evaluation, diagnosis and management of HF in primary care awaits more research 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Risk factor management Patient education Treatment: Non-pharmacological Treatment: Pharmacological When to refer? Cardiovascular risk factor targets National guidelines, lifestyle, pharmacologic measures for patients with high risk of developing HF and for those already diagnosed with HF [Class I Evidence, Level A Recommendation] Elderly Patients (>80 years) with sitting BP > 160/90 mmHg and standing systolic BP > 140 mmHg lower sitting BP to 150/80 mmHg [Class I Evidence, Level A Recommendation] Patient with vascular disease or diabetes with end-organ damage, prescribe target-dose ACEi or ARB [Class IIa Evidence, Level B Recommendation] Critical for successful therapy Best way to maintain adherence/compliance Patient information/handouts -Eg. Canadian Heart Failure Network (CHFN) http://www.chfn.ca/patient-education-tools Self-management, meds (when applicable) Action plan – what to do if symptoms worsen Multidisciplinary interventions appear beneficial (studies from academic centres only) 1) Physical activity and exercise training 2) Salt and fluid restriction & weight management 3) Reducing risk of serious respiratory infections 1) Physical activity and exercise training - Earlier studies: reduction in mortality - Cochrane review (2010) >3500 patients: Risk of death (mild-mod HF) ↔ [Level I-1 Evidence) Hospital Admissions ↓ - All studies: health-related quality of life ↑ - Exercise programs mainly aerobic [Class IIa Recommendation, Level B Evidence] 1) Regular daily physical activity that does not induce symptoms, for all patients with stable HF symptoms and impaired LV systolic function; to prevent muscle deconditioning [Class IIa Recommendation, Level B Evidence] 2) All patients should have a graded exercise stress test to assess functional capacity, identify angina or ischemia, and determine optimal target HR for exercise training 3) Exercise training should be considered when symptoms have stabilized and patient is euvolemic [Class IIa Recommendation, Level B Evidence] 4) Referral to cardiac rehabilitation program should be considered for all stable NYHA I to II HF patients 5) Moderate-intensity aerobic (30-45 mins) and resistance training, 3-5 x/wk for NYHA II to III, with LVEF < 40% can be considered 2) Salt and fluid restriction & weight management Symptomatic patients: No-salt-added diet (total 2-3g daily) Patients with fluid retention: low-salt diet (1-2 g total daily) [Class I Recommendation, Level C Evidence] 2) Salt and fluid restriction & weight management Significant renal dysfunction/fluid retention not easily controlled with diuretics: Monitor daily morning weight Fluid restriction 1.5-2 L per day [Class I Recommendation, Level C Evidence) 2) Salt and fluid restriction & weight management Patients with recurrent fluid retention who are able to follow instructions can be taught to adjust their diuretic dose based on symptoms and changes in daily body weight 3) Reducing risk of serious respiratory infections Pneumococcal vaccination Annual influenza vaccination [Class I Recommendation, Level C Evidence] Some differences between how to (pharmacologically) manage HF with reduced EF vs. preserved EF Treat probable HF ◦ Eg. Echocardiography results unavailable ◦ Use diuretic and nitrates for symptoms relief ◦ Consider ACEi and ß-blocker in the long-term 1. Type of heart failure: systolic or diastolic or mixed HF 2. NYHA class of symptoms 3. Renal function 4. Co-morbidities (e.g., COPD, anemia) 5. Life expectancy 6. Time needed to produce an effect 7. Goals of care or target symptom improvement including patient preferences 8. Goals of pulse and blood pressure reduction with HF medications 9. Common drug interactions (increase or decrease concentration) and side effects Drugs Aging (2013) 30:765–782 Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HF-REF) -Diuretic -ACEi (or ARB) and ß-blocker -Aldosterone antagonists -Digoxin -Nitrates/Vasodilators -Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids -Ivabradine -What about ASA/Antiplatelets? Diuretic Loop diuretic (eg. Furosemide) for congestive symptoms When symptoms clear, use lowest possible dose [Class I, Level C] If volume overload persists, despite optimisation of dose: add a second diuretic (eg. Metolazone or a Thiazide diuretic) [Class IIb, Level B] ACEi (or ARB) and ß-blocker All patients with HF and LVEF < 40% should receive target-dose combination therapy with an ACEi and ß-blocker [Class I, Level A] Asymptomatic patients with LVEF < 35% should receive an ACEi [Class I, Level A] ACEi (or ARB) and ß-blocker If cannot tolerate ACEi, substitute with ARB [Class I, Level A] Monitor serum Creatinine Patients optimally treated with ACEi and ßblocker with persistent HF symptoms, ↑ hospitalization Add ARB consult cardiologist/internist Addition of an ARB to ACE inhibitor and βblockade therapy modestly improves clinical outcome predominantly by reducing HF hospitalizations Monitor BP, K+, Renal function: use with caution! ONTARGET hypertension trial: 13% increased risk of renal dysfunction [Level I-1 Evidence] Aldosterone Antagonists/Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs) Spironolactone for patients with LVEF < 30% and severe HF symptoms HF symptoms despite optimal medical therapy Monitor renal function and electrolyte status [Class I, Level B] Aldosterone Antagonists/Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs) Eplerenone: up to 50 g reduces hospitalization and death in HF patients (NYHA II, LVEF < 30%) (EMPASIS-HF Trial) Digoxin Relieves symptoms Decreases hospitalizations In patients in sinus rhythm who have moderate-severe symptoms despite optimal medical therapy [Class I, Level A Evidence] Nitrates/Vasodilators Isosorbide Dinitrate plus Hydralazine added to standard therapy for African-American patients who have HF with reduced EF A-HeFT (African-American Heart Failure Trial) [Class IIa, Level A] Consider this combination for other HF patients who cannot tolerate recommended standard therapy [Class IIb, Level B] Source: Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2013; 29:168-181 (DOI:10.1016/j.cjca.2012.10.007 ) Copyright © 2013 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Recent study in patients with NYHA class II-IV symptoms and ejection fraction (EF) ≤ 40% Use of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (1 g daily) Modest reduction in cardiovascular mortality and hospitalization Ivabradine Inhibits the If channel Not yet approved Might be considered in patients who remain symptomatic with a heart rate > 70 bpm (despite optimal medical therapy eg.βblockers) to reduce hospitalizations and deaths because of HF On basis that resting HR independently predicts CV events, including HF hospitalization Antiplatelet agents such as aspirin should be administered ONLY to patients with HF who have a documented history of coronary artery disease and stroke or who are deemed high risk for CV events Treatment trials have been inconclusive, limited evidence-based recommendations Best available data is for ACEi and ARB therapy. Combo therapy for most patients (add ARB) [Class IIa, Level B] If HR is high, ß-blockers may be useful to prolong diastolic filling time and relieve pulmonary congestions Diuretics : for symptom control Once acute congestion cleared, use lowest dose compatible with stable weight and symptoms [Class I, Level C] Emphasis on management of comorbidities ◦ Diabetes ◦ Hypertension : Control diastolic and systolic as per Hypertension guidelines [Class I, Level A] ◦ Coronary Revascularization: CABG for patients whose ischemia affects cardiac function [Class IIa, Level C] Emphasis on management of comorbidities: ◦ Atrial Fibrillation: 50% of patients -ß-blocker or Digoxin to control ventricular rate -Restoration of sinus rhythm Thiazolidinediones Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors Common arrhythmia in HF Associated with higher rates of adverse clinical events Increased risk of thromboembolism including stroke Manage and classify according to current AF guidelines General approach : control rate Limited data to support a specific upper heart rate target Current CCS AF guidelines target rate < 100 bpm β-Blockers are preferred over digoxin for rate control Rate-lowering CCBs are acceptable alternatives in patients with HF-PEF Combination of β-blocker and digoxin is more effective than β-blocker alone When rhythm control is required because of symptoms, Amiodarone is preferred Unless contraindicated, oral anticoagulants should be initiated in patients deemed high risk for stroke as per current AF guidelines Primary Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD) therapy improves survival in patients with NYHA II-III ischemic and non-ischemic HF with EF ≤ 35% and in patients with a previous MI with EF ≤ 30%.91 ICD therapy does not provide any survival benefit early after an MI Cardiac Resynchronisation Therapy (CRT) Devices (aka Biventricular pacing) In combination with Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator (ICD) in less symptomatic HF patients [Level I-1 Evidence] CCS recommends combination for HF patients on optimal therapy with: NYHA II symptoms LVEF < 30% QRS duration > 150 msec [Level I, Class A] CCS recommendation: At initial HF diagnosis After HF hospitalization HF associated with any of the following: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Ischemia Hypertension Valvular disease Syncope Renal Dysfunction Other comorbidities Unknown etiology Treatment intolerance Poor compliance [Class I, Level C] Vasopressin Antagonists: improve volume overload and hyponatremia Eg. Tolvapatan is approved by the US FDA for hospitalized hypervolemic and euvolemic hyponatremia in HF Adenosine A1 Receptor Antagonists: arteriolar vasodilatation, improved renal function, natriuresis without activation of tubuloglomerular feedback Eg. Rolofylline Selective Phosphodiesterase Type 5 Inhibitors: vascular smooth muscle dilatation, role in the reversal of ventricular hypertrophy (inhibiting downstream hypertrophy signaling and improving ventricular function) Eg. Sildenafil Patients with HF-REF: Ryanodine receptor stabilizers, Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase isoform (SERCA) activators, blockers of the RAAS (direct renin inhibitors, aldosterone synthase inhibitors) Patients with HF-PEF: strategies target specific structural and functional abnormalities that lead to increased myocardial stiffness. ◦ Eg. Dicarbonyl-breaking compounds reverse advanced glycation-induced cross-linking of collagen and improve the compliance of aged and/or diabetic myocardium. Patient-centred decision making Open communication with patients and their families: critical concepts in high quality care Description of underlying condition + prognosis Exploration patient’s values, needs, goals + expectations of treatment. Discussion must take into account the psychosocial, cultural and spiritual and/or informational needs by patient or proxy Options for treatment and expected outcome - benefit vs. harm Explanation of conclusion of holding or withdrawing treatment Explain that patient will not be abandoned palliative care Likely to Benefit - reasonable likelihood that life support will restore/maintain organ function or likelihood of returning to prearrest status is moderate Unlikely to Benefit - there is almost certainly no chance that the person will benefit from CPR either because the underlying illness makes recovery or improvement unprecedented. Person unlikely to experience permanent benefit. Good End of Life care includes ongoing communication between the health care providers and the patient/POA What are we addressing? Code status Aggressiveness of management “along the way” Admissions to acute care vs. care at home and end-of-life planning When is the right time to have the discussion? Exploring end-of-life preferences, expectations Quality of life as a valuable goal of therapy Treatment modality: Improve symptom + prognosis vs. Symptom relief (at expense of survival) Brunner-La Rocca et al (2012) “End-of-Life preferences of elderly patients with chronic heart failure” ~75% not willing to trade survival time for excellent health 25%: equal groups willing to trade up to 6 months, >6 mo-1yr, >1yr Patients ≥ 75 slightly more willing to trade than younger patients During follow-up, patients willing to trade any survival time decreased Brunner-La Rocca et al (2012) continued: Who were the patients willing to trade survival time for symptom-free living? Older More females Lived alone Not married More signs and symptoms of CHF and poorer quality of life The next slides have some tools that may help with prognostication, and informing your discussions with patients and families Medical Care of the Dying 2006 No clear “transition point” When do you start PC? Costly and invasive therapies When do you say “no”? Sudden death (50%) Poor patient understanding of illness Reviewed 38,702 consecutive patients with first time admissions for heart failure Overall: 30 day fatality rate – 12% 1 year fatality rate – 33% If >75 y.o. and co-morbidities: 30 day fatality rate – 24% 1 year fatality rate – 60% Jong et al Arch Int Med (2002) EFFECT Score (http://www.ccort.ca/CHFriskmodel.aspx) Prediction score to stratify the risk of death in heart failure patients Enter age in years, RR and Systolic BP at hospital presentation, BUN, Sodium and list of comorbidities including: CVA, Dementia, COPD, Cirrhosis, Cancer and Anemia. Calculate EFFECT Score: http://www.ccort.ca/CHFriskmodel.aspx Mortality risk at 30 days: 30-Day Score 30-Day Mortality Rate (%) < 60 0.4 61-90 3.4 91-120 12.2 121-150 32.7 > 150 59.0 Mortality risk at one year: One-Year Score One-Year Mortality Rate (%) < 60 7.8 61-90 12.9 91-120 32.5 121-150 59.3 > 150 78.8 http://depts.washington.edu/shfm/index.php Insert age, gender, weight, EF, systolic BP, NYHA class level, medications and lab data Graph will appear showing mortality risk over 1,2, and 5 years SOB Pain (>70%!) Depression (60%) Myopathy Cachexia Cognitive impairment Goodlin J Am Coll Cardiology (2009) Consensus panels advocate provision of palliative care concurrent with efforts to prolong life in heart failure ACC/AHA Practice Guidelines Sudden death Arrhythmia Progressive Heart Failure Importance of communication with patient early in the disease: prognosis, advanced medical directives (living will), resuscitation wishes, identifying a substitute decision maker/power of attorney 1. 2. 3. 4. A clinical syndrome: impaired cardiac output and/or volume overload, concurrent cardiac dysfunction Progressive Associated with poor quality of life – frequent hospitalizations, poor survival Educate patients: communication, communication, communication! Teach patients to: -weigh themselves daily -recognize worsening symptoms -adjust diuretic dose, in appropriate patients -monitor salt and fluid intake Monitor clinical status of all patients with HF Monitor renal function, electrolytes Monitor BP, HR Perform medication reviews -q6months (minimum) -If status change, qfew days-2 weeks Delayed progression/prolong survival through early diagnosis, optimized pharmacotherapy, non-pharmacological treatments Manage side-effects Adherence, self-management strategies Complex cases – manage with support of cardiology consultation, specialty heart failure clinics Titrate doses slowly -ß-blocker increases slowly – double the dose every 2-4 weeks -ACEi increases slowly – double the dose every 1-2 weeks Optimize ß-blocker and ACEi -Decrease doses of diuretics, nitrates and other antihypertensives Refer to an interprofessional HF clinic for patient education and management Refer to a cardiac rehab program for individualized exercise training for all stable NYHA I to III HF patients Advanced care planning is an important part of patient care Disease trajectory difficult to follow Prognostication tools can be helpful Quality of life and exploration of patient preferences and expectations important part of high quality care Drug ACE Inhibitors Captopril Enalapril Lisinopril Perindopril Ramipril Trandolapril Beta-blockers Bisoprolol Carvedilol Metoprolol CR/XL** Start Dose Target Dose 6.25-12.5 mg TID 1.25-2.5 mg BID 2.5-5 mg OD 2-4 mg OD 1.25-2.5 mg BID 1-2 mg OD 25-50 mg TID 10 mg BID 20-35 mg OD 4-8 mg OD 5 mg BID 4 mg OD 1.25 mg OD 3.125 mg BID 12.5-25 mg OD 10 mg OD 25 mg BID* 200 mg OD * 50 mg BID if weight is >85 kg ** Not available in Canada Drug ARBs Candesartan Valsartan Start Dose 4 mg OD 40 mg BID Aldosterone Antagonists Spironolactone Eplerenone Vasodilatators Hydralazine Isorbide dinitrate Target Dose 32 mg OD 160 mg BID 12.5 mg OD 25 mg OD 50 mg OD 50 mg OD 37.5 mg TID 20 mg TID 75 mg TID 40 mg TID * 50 mg BID if weight is >85 kg ** Not available in Canada Class and Definition I Evidence or general agreement that a given procedure or treatment is beneficial, useful and effective II Conflicting evidence or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness or efficacy of the procedure or treatment IIa Weight of evidence is in favour of usefulness or efficacy IIb Usefulness or efficacy is less well established by evidence or opinion III Evidence or general agreement that the procedure or treatment is not useful or effective and in some cases may be harmful. Level and Definition A Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analysis B Data derived from a single randomized clinical trial or non-randomized studies C Consensus of opinion or experts and/or small studies.