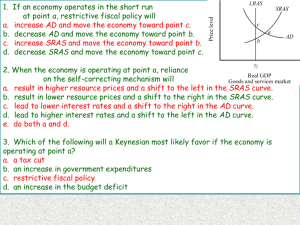

AD 1

advertisement

Spending Plan – formal or informal • Types of budgets: 1. Balanced: Expenditures = Revenues 2. Surplus: 3. Deficit: Expenditures < Revenues Expenditures > Revenues How the Federal Government Spends Defense Social Security 19% Net Interest 22% 6% Transportation 3.1% 15.5% 10.4% 24% Other Income Security Medicare and health A breakdown of the government expenditures at the federal level. Federal Government Spending • (Source: Economic Report of the President, Tables B-2 and B-22, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/ERP-2014/content-detail.html) How State & Local Governments Spend Insurance trusts Public welfare & Health 7.7% Education 32.2% 22.3% 7.9% Police & Fire Protection 12.2% 6.3% 7.1% 4.3% Transportation Utilities & liquor stores Interest on debt Administration & other State and Local Government Spending Spending by state and local government increased from about 10% of GDP in the early 1960s to 14–16% by the mid-1970s. The single biggest spending item is education. Source: (Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.) State & local taxes: Federal taxes: Property 15% Payroll 34% Payroll 12% Personal income 46% Other 3% Customs duties 1% Corporate income 12% User charges a 24% Excise taxes 4% Sales and excise 17% Personal income 10% From federal government 16% Other 4% 1997 Corporate income 2% Taxes vary by state1994 FL. MI, NH, TN Government (?) – no Income Tax How Taxes: NH motto: Live free or die... but they have a tax on parachute jumps Federal Tax Receipts Federal tax revenues have been about 17–20% of GDP during most periods in recent decades (Source: Economic Report of the President, 2015. Table B-21, https://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/cea/economic-report-ofthe-President/2015) Taxes!!!!! A. Types of Taxes or how the tax changes with income changes Progressive tax is one in which the average tax rate rises with income. - tax brackets, Federal Income Tax Proportional tax is one in which the average tax rate stays the same across income levels. - flat tax, Social Security, Medicare, sales tax? Regressive tax is one in which the average tax rate falls with income. - sales tax – higher income spend lower proportion on taxable goods • • • • • • • A sales tax of 7 % on medicine A state income tax with 3 tax brackets A property tax of $2.85 per $100 of assessed property value A tax of $8 on room occupancy in all city hotels A tax of 3 % on all wages earned in the city A sales tax of 5% on utilities A federal tax of $2 per pack of cigarettes. Expenditures > Revenue Expenditures < Revenues Discretionary changes in taxes and/or spending affect the Budget Debt/GDP Ratio Annual deficits do not always mean that the debt/GDP ratio is rising. During the 1960s and 1970s, the government often ran small deficits, so the debt/GDP ratio was declining over this time. In the 2008–2009 recession, the debt/GDP ratio rose sharply. (Source: Economic Report of the President, Table B-20, http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/ERP2015/content-detail.html) 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 (estimate) 2011 (estimate) 2012 (estimate) -377 -413 -318 -248 -161 -459 -1413 -1556 -1267 -829 1. Generally small deficits except during recessions. 2. Budget deficits generally increased during recessions and shrank during expansions, (automatic stabilizers, not discretionary policy) 3. Reductions in income tax rates and sharp increases in defense expenditures led to large deficits during the 1980s. 4. The deficits replaced by surpluses in the 1990s. 5. Real economic growth was strong and the inflation rate low during 80s and 90s 6. The combination of: -the 2001 recession -the economy’s sluggish recovery -the Bush Administration’s tax cut, and -increases in defense spending quickly moved the budget from surplus to deficit at the beginning of the new century. Federal Expenditures and Revenues Federal Government Expenditures and Revenues (as a share of GDP) 24% Expenditures 22% 20% Surplus Deficits 18% Revenues 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 • Note the growth of budget deficits during the 1980s and the movement to surpluses during the 1990s. • Since 2002, the deficits have been sizeable and they soared to peacetime highs during the recession of 2008-2009. Growth of Real Federal Government and Defense Expenditures Percent rate of change 8% 6% Total 4% 2% 0% Defense -2% -4% 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 • During the 1980s, rapid growth of defense spending pushed federal spending upward and contributed substantially to the large deficits of the decade. • During the 1990s, defense cuts retarded the growth of federal spending and thereby helped shift the budget to surplus. Fiscal Policy & Economic Performance: • In the 1960s, most economists believed fiscal policy was highly potent and could be used to smooth out the business cycle. • Confidence in the ability of policy makers to implement countercyclical fiscal policy has waned. • Most now believe that fiscal policy exerts only a modest impact on aggregate demand, much like the crowding-out and new classical models imply. • Since 1980, real growth has been strong during periods of both expanding (1980s and 2002-2006) and contracting (1990s) deficits. Price Level market selfadjustment may be a lengthy process. LRAS SRAS1 SRAS2 E2 P2 P1 e1 P3 E3 directs the Economy to full-employment AD1 AD2 Y 1 YF Goods & Services (real GDP) • Equilibrium below full employment. Two options 1. Wait for SRAS1 to shift out to SRAS2 2. Shift AD1 out to AD2 Expansionary Fiscal Policy This graph shows that since the economy was originally producing below potential GDP, any inflationary increase in the price level from P0 to P1 that results should be relatively small. Price Level SRAS2 LRAS SRAS1 P3 E3 P1 P2 e1 E2 restrains demand and helps control inflation. AD2 AD1 YF Y 1 Goods & Services (real GDP) • Equilibrium above full employment at Y1. 1. Will lead to the long-run equilibrium E3 at a higher price level as SRAS shifts to SRAS2. or 2. Reduce demand to AD2 and lead to equilibrium E2. Contractionary Fiscal Policy The economy starts above potential GDP. The extremely high level of aggregate demand will generate inflationary increases in the price level. A contractionary fiscal policy can shift aggregate demand down from AD0 to AD1, leading to a new equilibrium output E1, which occurs at potential GDP, where AD1 intersects the LRAS curve. There is a larger effect on the Price level with this case Decline in private investment Increase in budget deficit Higher real interest rates Inflow of financial capital from abroad Appreciation of the dollar Decline in net exports Price Level LRAS SRAS1 P0 P1 E0 e1 AD1 Y1 Y0 AD0 Goods & Services (real GDP) 1. Equilibrium at E0 2. AD decreases to AD1 and output falls to Y1 Price Level LRAS SRAS1 P0 P1 E0 e1 AD2 AD1 Y1 Y0 AD0 Goods & Services (real GDP) 3. While policy is being enacted, private investment has begun to recover. 4. AD has begun shifting back to AD0 on its own, the effects of fiscal policy over-shift AD to AD2. Price Level LRAS SRAS2 SRAS1 P3 E3 P2 e2 P0 P1 E0 e1 AD2 AD0 AD1 Y1 Y0 Y2 Goods & Services (real GDP) • The price level in the economy rises (from P1 to P2) as the economy is now overheating. • Unless the expansionary fiscal policy is reversed, wages and other resource prices will eventually increase, shifting SRAS back to SRAS2 (driving the price level up to P3). Price Level LRAS SRAS1 P2 P0 e2 E0 AD2 AD0 Y0 Y2 Goods & Services (real GDP) 1. Demand shifts AD out to AD2, and prices upward to P2. 2. Restrictive Fiscal Policy is considered Price Level LRAS SRAS1 P2 e2 P0 P1 E0 e1 AD2 AD0 AD1 Y1 Y0 Y2 Goods & Services (real GDP) 2. The price level falls (from P2 to P1) as the economy is thrown into a recession. 3. With the timing lag, fiscal policy does not work instantaneously. Price Level LRAS SRAS1 P2 P0 e2 Suppose that shifts in AD are difficult to forecast. E0 AD2 AD0 AD1 Y0 Y2 Goods & Services (real GDP) 4. Investment returns to its normal rate (shifting AD2 back to AD0). 5. The effects of fiscal policy over-shift AD to AD1. Price Level SRAS1 G H G P1 AD1 Y1 AD2 Goods & Services (real GDP) • Government deficit would shift AD1 to AD2. • Household saving keeps demand unchanged at AD1. Loanable Funds Market Real interest rate S1 S2 e1 no effect on the interest rate, real GDP, and unemployment. e2 r1 D1 Q1 Q2 D2 Quantity of loanable funds 1. Government borrows from the loanable funds market, increasing the demand (to D2). 2. People save for expected higher future taxes (raising the supply of loanable funds to S2.) 3. Loans increase, but interest rate doesn’t. Price Level LRAS1 LRAS2 SRAS1 SRAS2 P0 E1 E2 AD1 YF1 YF2 With time, lower tax rates promote more rapid growth (shifting LRAS and SRAS out to LRAS2 and SRAS2). AD2 Goods & Services (real GDP) 1. Lower marginal tax rates shifts AD1 out to AD2, and SRAS & LRAS shift to the right. 2. If the tax cuts are financed by budget deficits, AD may expand by more than supply, bringing an increase in the price level. Share of personal income taxes paid by top ½ % of earners 30 % 28 % 26 % 24 % 22 % 20 % 1964-65 Top rate cut from 91% to 70% 2001-2004 Top rate cut from 39.6% to 35% 1990-93 Top rate raised from 30% to 39.6% 1986 Top rate cut from 50% to 30% 1997 Capital gains tax rate cut 18 % 1981 Top rate cut from 70% to 50% 16 % 14 % 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 • Their share of taxes paid has increased as the top tax rates have declined. • This indicates that the supply side effects are strong for these taxpayers. O b a m a “Soaking the Rich?” • Since 1986 the top tax rate has been less than 40% . • The top one-half percent of earners have paid more than 25% of the personal income tax every year since 1997. • Well above the 14% to 19% from the 1960s and 1970s. 1. If an economy operates in the short run at point a, restrictive fiscal policy will a. increase AD and move the economy toward point c. b. decrease AD and move the economy toward point b. c. increase SRAS and move the economy toward point b. d. decrease SRAS and move the economy toward point c. 2. When the economy is operating at point a, reliance on the self-correcting mechanism will a. result in higher resource prices and a shift to the left in the SRAS curve. b. result in lower resource prices and a shift to the right in the SRAS curve. c. lead to lower interest rates and a shift to the right in the AD curve. d. lead to higher interest rates and a shift to the left in the AD curve. e. do both a and d. 3. Which of the following will a Keynesian most likely favor if the economy is operating at point a? a. a tax cut b. an increase in government expenditures c. restrictive fiscal policy d. an increase in the budget deficit 4. If the output of the economy is Y1, which of the following would a Keynesian economist be most likely to favor? a. a reduction in government expenditures b. an increase in government expenditures c. an increase in taxes d. continuation of the current tax and expenditure policies 5. If the output of the economy is Y1, which of the following would a new classical economist be most likely to favor? a. a reduction in government expenditures b. a reduction in taxes c. an increase in taxes d. continuation of the current tax and expenditure policies 6. When government expenditures exceed revenue from all sources, a. a budget deficit is present. b. the supply of money will increase. c. the government’s outstanding debt will decline. d. all of the above are true. 7. According to the Keynesian view, which of the following would most likely decrease aggregate demand? a. a decrease in tax rates b. a decrease in government expenditures c. an increase in transfer payments d. an increase in the budget deficit