Use Conditions - The Carter Center

advertisement

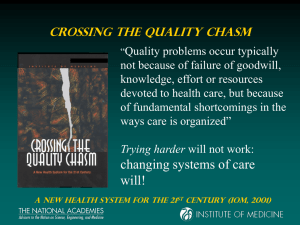

Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions A Report in the Quality Chasm Series Study Sponsors • Annie E. Casey Foundation • CIGNA Foundation • National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism • National Institute on Drug Abuse • Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration • Robert Wood Johnson Foundation • Veterans Health Administration COMMITTEE ON CROSSING THE QUALITYCHASM: ADAPTION TO MENTAL HEALTH AND ADDICTIVE DISORDERS MARY JANE ENGLAND (Chair) - Regis College, Weston, MA. PAUL S. APPELBAUM - University of Massachusetts Medical School SETH BONDER - Consultant in Systems Engineering, Ann Arbor ALLEN DANIELS - Alliance Behavioral Care, Cincinnati BENJAMIN DRUSS - Emory University, Atlanta SAUL FELDMAN - United Behavioral Health, San Francisco RICHARD G. FRANK - Harvard Medical School THOMAS L. GARTHWAITE - Los Angeles County Dept of Health Services GARY GOTTLIEB - Brigham and Women’s Hospital & Harvard Medical School KIMBERLY HOAGWOOD - Columbia University & NY Office of Mental Health JANE KNITZER - National Center for Children in Poverty, New York. COMMITTEE ON CROSSING THE QUALITYCHASM: ADAPTION TO MENTAL HEALTH AND ADDICTIVE DISORDERS A. THOMAS MCLELLAN - Treatment Research Institute, Philadelphia. JEANNE MIRANDA - UCLA. LISA MOJER-TORRES - Attorney in civil rights and health law, Lawrenceville, NJ. HAROLD ALAN PINCUS - University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and RAND - University of Pittsburgh Health Institute ESTELLE B. RICHMAN - Pennsylvania Department of Public Welfare JEFFREY H. SAMET - Boston University Schools of Medicine and Public Health and Boston Medical Center TOM TRABIN - Consultant in behavioral healthcare and informatics, El Cerrito, CA. MARK D. TRAIL - Georgia Department of Community Health. ANN CATHERINE VEIERSTAHLER - Nurse, advocate, person with bipolar illness. Milwaukee, WI CYNTHIA WAINSCOTT Chair, National Mental Health Association, Cartersville, Georgia. CONSTANCE WEISNER - University of California, SF, and Northern California Kaiser Permanente. Crossing the Quality Chasm a new HEALTH system for the 21st century (IOM, 2001) M/SU Health Care Compared to General Health Care • Increased stigma, discrimination, & coercion • More separate care delivery arrangements • Patient decision-making ability not as anticipated /supported • Less involvement in the NHII and use of IT • Diagnosis more subjective • More diverse workforce and more solo practice • A less developed quality measurement & improvement infrastructure • Differently structured marketplace Overarching Recommendation The aims, rules, and strategies for redesign set forth in Crossing the Quality Chasm should be applied throughout M/SU health care on a day-to-day operational basis but tailored to reflect the characteristics that distinguish care for these problems and illnesses from general health care. Mental, substance-use, and general health • Mental and substance-use conditions are frequently intertwined; • Both highly influence general health; • Improving care delivery and health outcomes for any one of the three depends upon improving care delivery and outcomes for the others. Mental and substance-use problems are pervasive, often unrecognized, and if not resolved, ultimately make themselves known – if not initially as mental or substance use problems, then as general health conditions. Overarching Recommendation Health care for general, mental, and substance-use problems and illnesses must be delivered with an understanding of the inherent interactions between the mind/brain and the rest of the body. Improving M/SU health care requires actions by: • Clinicians • Health care organizations • Health plans • Purchasers • State policy officials • Federal policy officials • Accrediting bodies • Institutions of higher education • Funders of research Individual clinicians should: • Support consumer decision-making and treatment preferences; • Use illness self-management practices; • Have effective linkages with community resources; • When coercion unavoidable, make the process transparent; • Screen for co-morbid conditions; • Routinely assess treatment outcomes; • Routinely share clinical information with other providers; • Practice evidence-based care coordination; and • Be involved in designing the National Health Information Infrastructure (NHII). Organizations providing care should: • Have polices to enable and support all actions required of clinicians (on prior slide); • Involve patients / families in design, administration, and delivery of services; • If serving a high-risk population (e.g., child welfare, criminal and juvenile justice) screen all entrants for M/SU problems • Involve leadership and staff in developing the National Health Information Infrastructure (NHII). Health plans and purchasers should • For consumers with chronic M/SU illnesses, pay for peer support and illness self-management programs that meet standards; • Use and provide consumers with comparative info on the quality of M/SU services to select providers; • Remove payment, service exclusion, benefit limits and other coverage barriers to accessing effective screening, treatment and coordination; • Support development of a quality measurement and reporting infrastructure; Health plans and purchasers (cont.) • Require all contracting organizations to appropriately share patient information; • Provide incentives for the use of electronic health records and other IT; • Use tools to reduce adverse risk selection of M/SU treatment consumers; and • Use measures of quality and coordination of care in purchasing / and oversight. • Associations of purchasers work to reduce variation in reporting / billing requirements. State policy-makers should: • Make coercion policies transparent, use info on comparative quality of providers and evidence-based treatment, and afford consumers choice; • Revise laws and other policies that obstruct communication between providers; • Create high level mechanisms to improve collaboration and coordination across agencies; • Use purchasing practices that incentivize use of EHRs and other IT; • Enact parity for coverage of M/SU treatment; • Reorient state procurement processes toward quality; and • Reorient state purchasing to give more weight to quality and reduce emphasis on grant-based mechanism DHHS to charge or create entities to: • Identify evidence–based practices; • Develop procedure codes for administrative data sets; • Use evidence–based approaches to dissemination and promote uptake of evidence-based practices; • Assure use of general health care opinion leaders (e.g., CDC, AHRQ) in dissemination; • Fulfill essential quality measurement and reporting functions; • Provide leadership in quality improvement activities; and • Improve coordination among federal agencies. Federal Government also should • Revise laws, rules, other polices that obstruct sharing of information across providers; • Fund demonstrations to transition to evidence-based care coordination; • Ensure that the emerging NHII addresses M/SU health care; • Authorize and fund an ongoing Council on the Mental and Substance-Use Health Care Workforce similar to the Council on Graduate Medical Education (Congress); • Support M/SU faculty leaders in health profession schools; • Provide leadership, development support and funding for R&D on QI in M/SU health care. Accreditors of M/SU health care organizations should: Adopt standards requiring: • Patient-centered decision-making throughout care; • Involvement of consumers in design, administration, and delivery of services; • Effective formal linkages with community resources; and • Use of evidence-based approaches to coordinating mental, substance-use and general health care. Institutions of higher education should: • Increase interdisciplinary teaching and learning to facilitate core competencies across disciplines; and • Facilitate the work of the Council on the Mental and Substance-Use Health Care Workforce. Funders of research should support: • Development and refinement of screening, diagnostic, and monitoring instruments to assess response to treatment; • A set of M/SU “vital signs”: a brief set of indicators—for patient screening, early identification of problems and illnesses, and for repeated use to monitor symptoms and functional status. • Research approaches that address treatment effectiveness and quality improvement in usual settings of care. • Research designs in addition to randomized controlled trials, that involve partnerships between researchers and stakeholders, and create a “critical mass” of interdisciplinary research partnerships involving usual settings of care.