for Social Work with a Focus on Child Protection

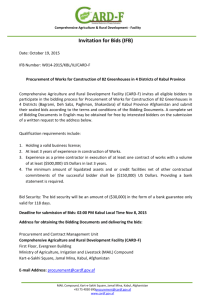

advertisement

Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work FINAL PROJECT REPORT Development of National Occupational Skills Standards for Social Work with a Focus on Child Protection Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Contract #: AFGA/RFP/2010/009 June 2011 to August 2012 1 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Project Summary Traditionally, Afghan children received protection and care within the extended family. When family supports proved insufficient, elders and community leaders stepped in to insure child and family wellbeing (Bragin, 2002). However, since 1979, Afghanistan has been the site of both armed conflict and natural disaster, placing enormous stress on children, families and communities (International Crisis Group 2010). Afghanistan, once a country that prided itself caring for its children, today ranks among the riskiest countries in the world on every indicator of child survival (UNICEF-CSO, 2012). In the other countries of the region and in many around the world, child protection risks are addressed through the provision of services by trained and qualified social workers. However, in Afghanistan, there has been no systematic education of or qualification for a professional child protection social work workforce. Further, government has not been able to use indigenous social work research to direct resources according to need. Instead, social services have been provided by agency staffers and volunteers without specific qualifications. In many cases external donors determined where resources have been directed, in the absence of university level social research on child protection (CPAN 2012). In order to tackle these problems on a systemic level, the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Martyrs, and Disabled (MoLSAMD) recognized that a formal system of social work for children and families would be needed, and that such a system should be based on both strong Afghan traditions and the contemporary research establishing factors that support child and family resilience in times of adversity. To this end, MoLSAMD, supported by UNICEF, launched the National Strategy for Children at Risk (NSFCAR) in 2006. NFSCAR provides a road map for building sustainable community-based child protection and family support systems. One of the key elements of NSFCAR is the development of a corps of professionally qualified social workers specialized in the area of child protection (MoLSAMD, 2006). In 2011, MoLSAMD, under the aegis of its National Skills Development program (NSDP,) contracted with Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York and Boston College Graduate School of Social Work (HC/BC) to begin the process of developing National Skills Standards for the profession along with curricula and syllabi necessary to cultivate a culturally relevant professional social work for children and families in Afghanistan. The one-year project was designed to initiate a process that has taken many years in other countries in the region where the academic standards for social work were developed first and the National Occupational Standards developed later. The objectives of the program were: Objective 1: Develop National Occupational Skills Standards (NOSS) for social work at three competency levels with a focus on child protection Objective 2: Develop, based on the NOSS, national syllabi and training manuals for child protection social work 2 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Objective 3: Support the establishment of a national training and certification program in social work for child protection The Scope of Work for the program required Hunter College/Boston College to: Finalize the development of National Occupational Skills Standards in line with the competency based training approach used by NSDP (DaCUM Methodology) Develop, on the basis of the agreed NOSS, national training curricula and syllabi Develop, in consultation with all stakeholders, a strategy for implementing the curricula through a national training and certification program; Convene and consult with an Advisory Committee comprised of organizations with social work training expertise in the Afghan context, first generation social work practitioners and representatives of the institution that will implement the NOSS/curricula 3 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Methodology The DaCUM Methodology The NSDP utilizes the DaCUM methodology to develop national skills standards for all occupations in Afghanistan. “DACUM” is an acronym for “developing a curriculum.” It “is an occupational analysis method aimed at the achievement of results that may be immediately applied to the development of training curricula” (ILO CINTERFOR). A participatory method, the requirements to succeed in a given occupation are identified, described and analyzed by the men and women who use them, in a particular setting and locale. A competency based framework, it lays out the knowledge skills and personal qualities as well as tools and machinery needed to get a particular job done (DeOnna, 2002). For the purpose of this document, the term competency will refer to the knowledge, skills and personal qualities necessary to accomplish the tasks of the profession (Bragin and Garcia 2009). Normally, DaCUM has been applied only to vocational standards, as it is best suited to a step by step breakdown of tasks that may be repetitive, sequential and prescribed. It is designed for the production of curricula for training manuals, rather than university level syllabi (ILO CINTERFOR, 2011). In order to utilize the methodology for the social work profession, while remaining firmly within the competencies framework, it was necessary to make some modifications to insure that the information gathered reflected the breadth and range of participant experience as discussed by Key (2008). The DaCUM methodology was used, as agreed with NSDP, to develop the standards and curricula required by the contract. Data Gathering Process The project began with a thorough desk review of the many assessment documents completed by national and international participants regarding child protection social work in Afghanistan in order to insure a comprehensive and inclusive approach and that maximum advantage was taken of existing studies and materials. The next step was the formation of an advisory committee comprising as many of the stakeholders in child protection social work as could be identified and engaged quickly. Included in the advisory committee were Government Ministries that employed or wished to employ social workers for children and families, including the Ministries of the Interior, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Culture Youth and Sports, Ministry of Public Health and the sponsoring Ministry, MoLSAMD. Also included were Afghan and international non-governmental organizations who employed people to provide social work services to children and families on the community level and in institutions, in coordination with the Ministries and UNICEF. Working with the advisory committee, key informants were identified as well as participants for focus groups in four provinces and Kabul city, including Balkh (north), Nangahar (east), Herat (west), Kabul city in the central region and Kandahar (south). Unfortunately, the team was unable to travel south for security reasons therefore a limited number of participants were seen in Kabul. 4 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Relying on the advice of the advisory committee members, representatives from the three levels of social work were recruited to participate; community workers, social workers, and social work managers or supervisors. Service users were also recruited on two levels, grass roots service users, and also those professionals and administrators who needed professional social workers to support their own work. Because of the distinct and strong regional differences in Afghanistan, the team travelled to centrally located cities in three of the four main regions of the country in addition to Kabul to be sure to include a more diverse perspective. DaCUM Sessions Demographic Information from DACUM Sessions # of Participants Jalalabad 73 Mazar-i-Sharif 70 Herat 94 Kabul 82 TOTAL 319 Total participants for each level Community Social Worker 142 Social Worker 102 Social Work Manager 75 Total number of participants for each level by gender Community Social Worker Male 78 Female 64 Male 56 Female 46 Male 54 Female 21 Social Worker Social Work Manager 5 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work The Key Informant Interviews The key informants were selected by the advisory committee for their singular and expert knowledge of the need for and practice of child protection social work in their area of experience. Included were members of service organizations, religious experts, and lawyers for children. They represented both practitioners and officials whose work required social work expertise. The key informants were briefed on the purpose of the project and asked to comment in general before being asked to define social work as they saw it. Subsequently, they then described the role of social workers and the knowledge, skills, and personal qualities that a social worker would need to be successful. While the key informants are included in the overall DaCUM Session data on participants, they are listed separately here. Nineteen were managers, officials or members of the judiciary, two were social workers, six were women, and 15 were men. Key Informant Interviews Kabul Social Work Manager Level CiC CFA Save the Children Aschiana Medica Terre des Hommes Social Worker Level Aschiana Ministerial and Allied Professionals Working with Social Workers International Legal Foundation Ministry of Haj Directorate of Orphanage UNDP – Ministry of Culture, Youth Total Number of Key Informants 6 Total By Gender 3 2 2 4 1 2 2-F, 1-M 1-F. 1-M 1-F, 1-M 4-M 1 -F 2-M 2 2-M 2 1 1 1 21 1-F, 1-M 1-M 1-M 1-M 6-F, 13-M Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Achievements Hunter College/Boston College have achieved the overall objectives of the project and have delivered the following outputs: Inception Report (July 2011) A Baseline Review of the Literature (March 2012) National Occupation Skills Standards at three levels- Community Social Work Associate (Level 5), Social Worker (Level 6), and Social Work Manager/ Administrator (Level 7) - including an imbedded competency based evaluation system suitable for University accreditation. The NOSS were developed, in consultation with members of the Advisory Board based on data gathered utilizing the DaCUM methodology and key informant interviews. (August 2012) Curricula and syllabi which meet the requirements of and are pegged to the NOSS, at the Associates, BSW and MSW level. The draft curricula were revised based on MoHE standards and are available in English, Dari and Pashto. (August 2012) Three CD-ROMs containing all of the necessary readings required for each of the curricula. (April 2012) An agreement from the Ministry of Higher Education to take social work education forward, beginning with the BSW, through Kabul University. (July 2012) An academic paper on methodology, insuring that the work is transparent, traceable and replicable by others. (submitted September2012) 7 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Modifications and Responses to Challenges Initiating the process of establishing the foundation for a fully developed profession in one year’s time required adaptation as the partners, together, learned from experience in the field. This included understanding the nature of professional education in Afghanistan and the needs and resources originating from the field. Therefore, some modifications were necessary and agreed to by the parties in order to insure that the actual output took the development of professional social work for child protection forward in the specific context of Afghanistan. EU Technical Cooperation in Social Protection Project Upon arrival in Kabul in July 2011, it was immediately apparent during initial meetings with UNICEF and NSDP that an important aspect of project implementation would include close coordination with a recently launched initiative, the EU Technical Cooperation in Social Protection Project, which was being implemented in collaboration with MoLSAMD. Discussions between the two project teams ensued and it was agreed that, since the two projects had shared goals, it would be critically important to work together. The Development of National Occupational Skills Standards for Social Work with a Focus on Child Protection Project had a narrower, more specific remit and fit well as a component of the larger EU Technical Cooperation in Social Protection Project. Members of the Hunter College/Boston College Project Team participated in the EU project’s Executive Committee and Working Group in order to facilitate coordination and cooperation and to avoid duplication. Additionally, the Child Protection Advisory Committee for this project became a sub-committee of the EU project’s Executive Committee and its members were drawn from the Executive Committee’s membership, supplementing where specialists in children or social work were needed. This project focused exclusively on those aspects that pertained to post-secondary education and performance standards for social work in child protection. NOSS Levels The level numbers assigned to the NOSS developed by Hunter College/Boston College evolved over the course of the project. Initially, the discussions focused on developing NOSS for Levels 3, 4 and 5. This changed over the course of project implementation and after much discussion with NSDP, UNICEF and other key stakeholders, it was agreed that the NOSS developed by Hunter College/Boston College were for Levels 5, 6 and 7. Level 5, a post –secondary paraprofessional qualification under the auspices of NSDP, was reviewed by a team including an international senior advisor, an expert from NSDP, an Afghan MSW and an Afghan child protection specialist to insure the utility of the standards. Level 5, an associate’s level qualification, was completed to the satisfaction of NSDP. For Levels 6 and 7, the agreement to have Kabul University serve as Implementing Partner required modifications to the project plan in order to comply with the rules, procedures and by-laws of MoHE regarding curriculum development. This included separating out the NOSS for levels 6 and 7, the academic levels, for a lengthy academic vetting process through MoHE and Kabul University. International experts including the President of the International Association of Schools of Social Work have been contacted and have agreed to provide supportive mentoring to the university upon request. 8 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Security situation in Afghanistan The security situation in Afghanistan was constantly changing throughout the course of project implementation. This had the greatest impact on the location and duration of the DaCUM sessions which were conducted between October 2011-January 2012 in Jalalabad, Mazar-e-Sharif, Herat and Kabul. The team was unable to travel to Kandahar to conduct DaCUM sessions on site so, instead, information was gathered in Kabul. Additional Deliverables During the course of project implementation, additional deliverables were requested in order to support the breadth of data gathered, transparency and replicability of the methodology utilized. In order to ensure that the work was contextually appropriate and that it built upon those competencies already established for child protection social work in Afghanistan, a baseline literature review was conducted which focused on knowledge and information regarding social work education, training and coaching projects implemented in Afghanistan over the previous 10 years. Secondly, a publishable paper on the use of the DaCUM methodology was produced and submitted for publication to a professional social work journal . Field Testing of Curricula The ‘field testing’ of the curricula and syllabi was accomplished by having the Faculty of Social Science, Kabul University thoroughly review and discuss in detail the draft documents with the project team so that members of the Faculty could make the adaptations needed to meet university requirements. System of Evaluation A competency based system of evaluation was imbedded in the NOSS, curricula and syllabi on all three levels. For Level 5, a social work expert in international evaluation standards worked alongside the NSDP team and an Afghan social work expert to develop appropriate criteria based on the Afghan context. For Levels 6 & 7, the project team worked closely with the Faculty of Social Sciences at Kabul University to ensure that imbedded in the curricula was a competency based evaluation system suitable for University accreditation, that will be reviewed by the proper authorities at the MoHE and Kabul University, going forward. 9 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Recommendations and Way Forward I. From MoLSAMD to MoHE: making the connection The NOSS Levels 6 and 7 are a critical part of the policy document that is required by the MoHE in order for a new department to be added to a University faculty. The NOSS along with the curriculum answer the important questions that the MoHE requires to be addressed including: 1- What skills and knowledge do the graduates need to do the job of a social worker? 2- What subjects are the faculty going to offer to meet these needs? In order for this to happen, the NOSS must be translated into Dari, preferably by University approved translators, including Afghan MSWs who are familiar with both the language and nature of the work. II. Assisting Kabul University, Faculty of Social Sciences Steering Committee to Move Forward It has been recommended to the Faculty Steering Committee that they contact the International Association of Schools of Social Work to request assistance in developing the needs assessment for the Faculty of Social Sciences. Follow-up with the Faculty Steering Committee will help expedite this process. It is anticipated that further assistance to the Faculty of Social Science would be dependent on their needs as identified in their needs assessment. III. Developing Afghan champions for the Social Work profession Below are some key elements that may be important for social work to become an integral part of the Afghan educational system and a recognized profession in Afghanistan: Financial support for study tours and exchanges in cooperation with IASSW, so that academics and members of MoLSAMD can engage with social work educators and social work practitioners around the region and, if possible, in other parts of the world; Financial support for two people to complete MSW degree’s , possibly one person from the University and one person from MoLSAMD; Translate the NOSS and develop the policy document for presentation to the Curriculum Commission of the MoHE; Utilize the AA curriculum for Community Social Work Associate(already pegged to the NOSS and to the Coaching Agencies’ training programs) to begin to develop a certificate in social work at the MoLSAMD Institute by offering credit bearing courses and creating a career ladder for community workers; When the MSW candidates return with their degrees they will be in a position to lead the process of developing the social work education, going forward. 10 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work Appendices Appendix A: Appendix B: Appendix C: Appendix E. Appendix F. Inception Report Literature Review National Occupation Skills Standards for Community Social Work Associate (Level 5), Social Worker (Level 6), and Social Work Manager/ Administrator (Level 7) Curricula and syllabi at the Associates, BSW and MSW level (English, Dari and Pashto) An English-Dari lexicon of social work terminology A publishable article on utilization of the DaCUM methodology Appendix G: Final Financial Report Appendix D: In addition three CD-ROMs containing all of the readings required for each of the curricula have been delivered to UNICEF, NSDP, and the Faculty of Social Sciences of Kabul University. 11 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work References Adams, R. E. (1975). DACUM: Approach to curriculum, learning, and evaluation in occupational training. Ottawa, Canada: Department of Regional Economic Expansion. Bragin, M. (2002). Lost and Found: Addressing the needs of young people affected by the conflict in Afghanistan: needs assessment and program recommendations. Kabul: UNICEF Afghanistan Bragin, M., and Garcia M. (2009). Competencies required to design and implement programs for children and adolescents affected by violence and disaster: are these competencies those of international social work? Journal of Global Social Work Practice 2 (2), http://www.globalsocialwork.org/vol2no2.html Conway, A., and Jeris, L. (2006). Models, Models Everywhere and Not a One that Fits? Cross-cultural Implementation of a DACUM-inspired Process: Unpublished conference presentation: Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education, University of Missouri-St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, October 4-5, 2006. Retrieved July 2011 from: http://www.umsl.edu/continuinged/education/mwr2p06/pdfs/A/Conway_&_Jeris_Models.pdf deOnna, J. (2002). DaCUM: A versatile competency-based framework for staff development. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 18 (1) 5-13. Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder. Ohio State DACUM Process Page. (2006). Retrieved July 2012, from http://www.dacum.com/ohio/dacumpro.htm Healy, L. & Links, R. (2011). Handbook of international social work: Human rights development and the global profession. Oxford, Hugman, R, Nguyen Thi Thai Lan & Nguyen Thuy Hong (2007). Developing social work in Vietnam. International Social Work.50 (2):197-211. International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW) and International Federation of Social Work (IFSW) (2004). Global standards for the education and training of the social work profession. Adopted at the General Assemblies of IASSW and IFSW in Adelaide, Australia. Retrieved September, 2009, from http://www.ifsw.org/cm_data/GlobalSocialWorkStandards2005.pdf International Crisis Group (2011). Aid and conflict in Afghanistan. Asia Report Number 10. http://www.crisisgroup.org/en/regions/asia/south-asia/afghanistan/210-aid-and-conflict-inafghanistan.aspx 12 Hunter College School of Social Work, City University of New York Boston College Graduate School of Social Work ILO CINTERFOR (2011). Basic Concepts in Labour Competency. Retrieved June 2011 from http://www.buildproject-management-competency.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/ILOs-FAQs-for-CompetencyDevelopment.pdf Key, L. (2008) The development of culturally relevant social work practice in Sarawak, Malaysia. In M. Gray, J. Coates & M. Yellowbird, (Editors) (2008) Indigenous social work around the world: Towards culturally relevant education and practice. Farnham, England & Burlington, VT: Ashgate. Miller, K. (2012). When you need to know quickly: the efficiency and versatility of focus groups for NGOs in conflict and post conflict settings. Intervention, 10 (2) 168-170. Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Martyrs and Disabled (MoLSAMD). (2006). National strategy for children ‘at-risk’: A better future for Afghanistan’s vulnerable children and their families. Available from http://lib.ohchr.org/HRBodies/UPR/Documents/Session5/AF/AFG_Afghanistan_National_Strategy_f or_Children_at-risk.pdf Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Martyrs and Disabled (MoLSAMD). (2008). Strategic plan: 2008–2013. (Draft Plan, 3 January 2008). Afghanistan, Author. Norton, R. (1997). DaCUM Handbook (2nd edition). Columbus: OH: The Ohio State University Muhmad, W. H. (2010). Child protection system, prevention, and response to child protection in Afghanistan. Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs, Martyrs and Disabled. Available from http://www.unicef.org/eapro/DM_shanghi_CPAN_meeting.pdf UNICEF & CSO (2012).Afghan Mutliple Indicator Cluster Survey: Monitoring the situation of women and children 2010-2011. Xu, Q. (2006). Defining International Social Work: A Social Service agency perspective. International Social Work, 49(6), 679-692. Yuen-Tsang A. & Ku, B. (2008). A journey of a thousand miles begins with one step: The development of culturally relevant social work education; In M. Gray, J. Coates & M. Yellowbird, (Eds) (2008) Indigenous social work around the world: Towards culturally relevant education and practice (pp.177-179). Farnham, England & Burlington, VT: Ashgate. 13