Cognitive_Economics_.. - University of Michigan

advertisement

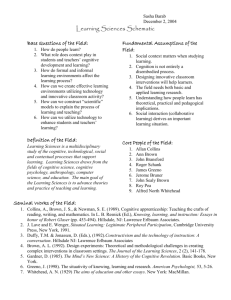

Cognitive Economics and Human Capital Robert J. Willis University of Michigan Presidential Address Society of Labor Economics, Chicago, May 4-5, 2007 Organizing Committee for 2007 SOLE Meeting • • • • • • • • • Martha Bailey John Bound Charlie Brown Mike Elsby Mike Hurd David Lam Justin McCrarry Bob Schoeni Gary Solon • Frank Stafford • Rebecca Thornton 1/65 Thanks for Helpful Discussions and Comments on this Talk • • • • Dan Benjamin Jim Heckman Miles Kimball Jack McArdle 2/65 Goal of My Talk • Describe a new research program integrating psychological and economic theories and new data collection that I am pursuing with colleagues. • The research that I describe has been motivated by my role during the past dozen years in overseeing the design of the Health and Retirement Study, a longitudinal survey of over 20,000 Americans over the age of 50 that began in 1992 with the support of the National Institute on Aging and Additional Support from the Social Security Administration 3/65 Goals (cont.) • The HRS has given me an appreciation of the value of embedding economics within the broad scope of the social, biological and medical sciences • On the one hand, among all of these sciences, economics offers the most coherent theoretical framework, including – life cycle theories of individual and family behavior – static and dynamic theories of markets, general equilibrium and economic growth – tight linkage of positive theories of behavior and normative theories of welfare and policy evaluation 4/65 Goals (cont.) • On the other hand, theory and measurements from other sciences can increase the power of economics to deal with the issues that the HRS is designed to address • In turn, I will argue, the power of cognitive psychology will be enhanced by integration with human capital theory • In this talk, I focus on the value of bringing theory and measurement from cognitive psychology and cognitive economics into the HRS 5/65 Why Cognition? • Increased complexity of decisions faced by older Americans – increased longevity, advances in medical technology – increased scope for choice due to decline of defined benefit pensions, growth of 401(k), etc. • Decisions concerning savings and wealth management, health care decisions, retirement decisions are cognitively demanding – The cognitive abilities of older Americans are highly heterogeneous and changing as they age 6/65 Cognition and Survey Data • Methodogical reason for measuring cognition – Information provided by survey responses to the HRS are related to cognitive status of respondent – Cognitive factors that influence survey response may also influence behavior in the real world – Implies need to jointly model behavior and survey response in analyzing data 7/65 Outline • • • • What is Cognitive Economics? Cognition and Probabilistic Thinking Cognition and Human Capital Use it or Lose It? Retirement and Cognition 8/65 Cognitive Economics The Economics of What is in People’s Minds Three Themes of Cognitive Economics 1. New Types of Data 2. Heterogeneity 3. Finite and Scarce Cognition 10/65 1. Innovative Survey Data • • • • • survey measures of expectations survey measures of preferences happiness data fluid intelligence data crystallized intelligence data 11/65 2. Individual Heterogeneity • • • • heterogeneous expectations heterogeneous preferences heterogeneous emotional reactions heterogeneous views on how the world works (folk theories) 12/65 3. Finite and Scarce Cognition • Finite cognition=the reality that people are not infinitely intelligent. • Scarce cognition=some decisions required by our modern environment—at work and in private lives—can require more intelligence for full-scale optimization than an individual has 13/65 Some Research Questions in Cognitive Economics • Seek to make innovations in economic theory and measurement to address: – What are people’s limitations in knowledge, memory, reasoning, calculation? – What is the role of emotion, social context, conscious vs. unconscious judgments and decisions? – What is the role of health as determinant, outcome and context for economic activity, decisions and well being? – What is connection between economic welfare and measures of well being? – Etc. 14/65 Cognition and Probabilistic Thinking What is the mapping between probability beliefs in people’s minds and the decisions they make? Probabilistic Thinking and Behavior in the Economy and on Surveys • The HRS provides detailed measurement of the variables that enter into a broad life cycle economic model 16/65 HRS Measures Components of Lifetime Budget Constraint • Income – from labor, assets, government transfers, family transfers • Wealth/Portfolio Composition/Insurance – from personal assets, future streams of employer pensions, social security benefits, value of inheritances received or bequests given • Labor Supply and Earnings – hours, weeks, occupation, retirement • Consumption and Time Use – goods and services, out-of-pocket medical expenses, transfers to children and others 17/65 But Conventional Life Cycle Economic Models Include More Variables • Current decisions based on effect of decision on lifetime expected utility – Separation of Beliefs and Preferences • Product of utilities and probabilities in each period – Forward-Looking • Sum over time from now through (uncertain) end of life • Discounting by time preference – Feasible utilities depend on current and future resources – Future resources, in turn, depend on current decisions 18/65 Probabilistic Thinking • Traditionally, economists make assumptions about agent’s probability beliefs (e.g. rational expectations) • The HRS provides detailed questions about those probability beliefs that enter into a broad life cycle economic model • These questions have stimulated a growing body of research in which probability beliefs become part of the data of economic models 19/65 Direct Measurement of Subjective Probability Beliefs in HRS Probability questions use a format pioneered by Tom Juster and Chuck Manski (Manski, 2004) HRS Survival Probability Question: “Using a number from 0 to 100, what do you think are the chances that you will live to be at least [target age X]?” X = 80 for persons 50 to 70 and increases to 85, 90, 95, 100 for each five year increase in age 20/65 Two Key Findings From Previous Research on HRS Probability Questions 1. On average, probabilities make sense – Survival probabilities conform to life tables and are predictive of actual mortality (Hurd and McGarry 1995, 2002; Sloan, et. al., 2001 ) – Bequest probabilities behave sensibly (Smith 1999), Perry (2006) – Retirement incentives can be analyzed using expectational data (Chan and Stevens, 2003) – People can predict nursing home entry (Finkelstein and McGarry, 2006) – Early Social Security Claiming Depends on Survival Probability (Delevande, Perry and Willis, 2006) , (Coile, et. al., 2002) 2. Individual probabilities are very noisy with heaping on focal values of "0", "50-50" and "100“ (Hurd, McFadden and Gan, 1998) 21/65 Survival Probabilities: Accurate on Average with Heaping on Focal Values Figure 1. Distribution of Survival Probabilities to Target Age by Age of Respondent .15 50-64 0 .05 .1 Subjective Mean= 66% Life Table = 59% Subjective Mean= 57% = 58% 0 .05 .1 Life Table .15 75-90 Subjective Mean= 36% .1 Life Table = 23% 0 .05 Density .15 65-74 0 50 100 Survival Probability Graphs by Age 22/65 10 Year Mortality Rate vs. Subjective Survival Probability to Age 75 3.00 2.76 2.49 2.50 Odds Ratio (50%=1.0) Odds Ratio of Death by t+10 2.00 1.47 1.50 1.43 1.22 1.00 1.00 0.86 0.85 0.79 0.68 0.70 80 90 0.50 0.00 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 100 Probability of survival to age 75 Subjective Survival Probability at Time t Source: Mortality Computations from HRS-2002 by David Weir 23/65 10 Year Mortality Rate vs. Subjective Survival Probability to Age 75 3.00 2.76 Strongest relationship between subjective and objective risks for people with low subjective survival beliefs 2.49 2.50 Odds Ratio (50%=1.0) Odds Ratio of Death by t+10 2.00 1.47 1.50 1.43 1.22 1.00 1.00 0.86 0.85 0.79 0.68 0.70 80 90 0.50 0.00 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 100 Probability of survival to age 75 Subjective Survival Probability at Time t Source: Mortality Computations from HRS-2002 by David Weir 24/65 . Histograms of Responses to Probability Questions in the HRS .3 .2 .2 F r a c tio n Social Security less generous Double digit inflation F r a c tio n A. General Events .1 .1 0 0 0 100 0 .3 .2 .2 0 0 0 0 50 W ill L iv e T o B e 7 5 100 .3 .4 .2 100 .1 .2 Leave inheritance Work at age 62 50 In c o m e W ill K e e p U p W ith In fla tio n F r a c tio n .6 F r a c tio n C. Events with Personal Control 100 .1 .1 Survival to 75 Income increase faster than inflation 50 D o u b le -D ig it In fla tio n F r a c tio n .3 F r a c tio n B. Events with Personal Information 50 S o c ia l S e c u rity T o B e L e s s G e n e ro u s 0 0 0 50 W ill L e a ve In h e rita n c e > = 1 0 ,0 0 0 100 0 50 W ill W o rk A t A g e 6 2 100 25/65 Are Benefits of Greater Individual Choice Influenced by Quality of Probabilistic Thinking? • Trend of increasing scope for individual choice in public and private policy, especially as it affects those planning for retirement or already retired – Private sector shift from defined benefit to defined contribution pension plans – Proposals for “individual accounts” in Social Security – Choice of when/whether to annuitize – Choice of medical insurance plans and providers by employers and by Medicare, new Medicare Prescription Drug program • Economists generally view increased choice as a good thing, but … – General public wonders whether people will make wise use of choice – Decisions faced by older individuals balancing risks and benefits of alternative financial and health care choices are genuinely difficult 26/65 Quality of Probabilistic Thinking and Uncertainty Aversion • Lillard and Willis (2001) began to look at the pattern of responses to probability questions as indicators of the degree to which they indicate people’s capacity to think clearly about subjective probability beliefs • We explored the idea that focal answers of “0”, “50” and “100” were perhaps indicators of less coherent or well-formed beliefs than non-focal (or “exact”) answers. 27/65 Index of Focal Responses We treated the probability questions like a psychological battery and constructed an empirical propensity to give focal answers of “0”, “50” or “100” number focal answers Index of Focal Answers = total number of probability questions We found that people who had a lower propensity to give focal answers tended to have higher wealth, had riskier portfolios, and achieved higher rates of return, controlling for conventional economic and demographic variables 28/65 Uncertainty Aversion • We hypothesized that people who give more focal answers are more uncertain about the true value of probabilities • If the uncertainty is about a repeated risk, such as the return to a stock portfolio held over time, we show that people who have more imprecise probability beliefs (i.e. are more uncertain about the “true” probability) will behave more risk aversely • Intuition can be shown with coin flipping example 29/65 Example: Increasing Uncertainty about Pr(Heads) Leads to Increasing Risk with Repeated Coin Tosses, Causing Risk Averse Person to Prefer Coin with Known Risk Flip two coins. $100 prize for each heads Payoff Belief about “success parameter” $0 $100 $200 Fair coin 0.25 0.50 0.25 Uniform Distribution 0.33 0.33 0.33 Two Head or Two Tails 0.50 0.00 0.50 •Increased uncertainty causes mean-preserving spread in payoffs because payoff probability is a non-linear function of success parameter, ie.. Pr(200), P(0) are concave functions of p squared, q squared 30/65 Theory of Survey Response to Probability Questions • What is the relationship between the probability beliefs that people have in their head and the answer that they give to probability questions on the HRS? • To answer this question, requires a theory of survey response. • It would be convenient if people gave the expected value of their subjective prior belief. But this is cognitively difficult and the high fraction of focal answers seems inconsistent with this interpretation. 31/65 Modal Response Hypothesis • An alternative hypothesis is that when asked to give a single number between "0" and "100", the individual gives the "most likely" probability among all possible probabilities. This is the mode of the subjective prior. • Lillard-Willis (2001) • Under this hypothesis, people are more likely to give focal answers the greater their uncertainty about the true probability • Reversing this idea, under the MRH, we can estimate the degree of uncertainty from the pattern of probability responses on the survey. • Hill-Perry-Willis (2005) 32/65 Some Further Results on Subjective Probabilities • There is “optimism factor” common across all probability questions which is correlated with stock-holding and associated with being “healthy, wealthy and wise” • Kezdi and Willis (2003) • HRS has added direct questions on stock returns – stockholding is related to probability beliefs • Kezdi and Willis (2003) and Dominitz and Manski (2006) – most people do not believe that stocks have positive returns, despite the equity premium that economists know about • Persons who provide more precise probability answers also exhibit less risk aversion on subjective risk aversion questions in the HRS, and they save a higher fraction of their full wealth. • Sahm (2007), Pounder (2007) • In 2006, HRS added questions to those who answer “50” to see whether they mean “equally probable” or “just uncertain”. 75% indicate they are uncertain. 33/65 Measurement of Cognition in the HRS • HRS has included cognitive measures from the outset, but mostly focused on memory in order to trace cognitive decline. • Re-engineering HRS cognitive measures – Led by Jack McArdle, a cognitive psychologist and HRS co-PI, we have begun a project to “re-engineer” our cognitive measures in order to improve our understanding of the determinants of decision-making about retirement, savings and health and their implications for the well-being of older Americans 34/65 Measurement of Cognition in the HRS (cont.) • Separate HRS-Cognition Study – Begins with a separate sample of 1200 persons age 50+ who will receive about three hours of cognitive testing of their fluid and crystallized intelligence plus parts of the HRS questionnaire on demographics, health and cognition – Followed a month later by administration of an internet or mail survey of questions designed by economists on financial literacy, ability to compound-discount, hypothetical decisions about portfolio choice, long term care – Finally, telephone follow-up with HRS cognition items and subjective probability questions – Analysis of data will guide re-engineering of cognitive items for HRS-2010 35/65 Cognition and Human Capital integration of cognitive psychology and human capital theory Cognition and Human Capital • Understanding the connection between how people think and their economic behavior has recently emerged as an important topic in behavioral economics, experimental economics and neuroeconomics. It has even provoked a counter-reaction in the recent case for “Mindless Economics” by Gul and Pesendorfer • Cognitive economics, the term I shall use for this broad area, emerged as an important theme in labor economics nearly half a century ago with the theory of human capital 37/65 Cognition and Human Capital (cont.) • Cognitive capacity is producible human capital – Indeed, much of the theory of human capital is a theory of the demand and supply of cognitive capacity • Cognitive psychology has a theory of the development of “fluid and crystallized” intelligence over the life cycle which is largely unknown to economists • Cognitive psychologists who work in this field appear never to have heard of the theory of human capital • In the last portion of this talk, I want to identify the potential gains from trade of the two theories 38/65 Theory of Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence (Gf/Gc) • (Near) consensus theory of intelligence is embodied in Woodcock-Johnson battery of cognitive tests used in HRS-cognition study. – McArdle, et. al. (2002), Horn and McArdle (2007) • Primary abilities structured into two principal dimensions – Fluid intelligence (Gf) represents measurable aspects of the outcome of biological factors on intellectual development (i.e., heredity, injury to the central nervous system) – Crystallized intelligence (Gc) is considered the main manifestation of influence from education, experience and acculturation 39/65 What is fluid intelligence? • Fluid cognitive functioning can be thought of as all-purpose cognitive processing not necessarily associated with any specific content domain • Aspects of fluid cognition – Working memory – Executive function or cognitive control – Ability to abstract, to do hypothetical thinking 40/65 numerical How fluid intelligence is related to psychometric g or IQ Ravens matrix score is most loaded on g. Figure shows correlation of other tests with g. Colors indicate nature of test Distance from center indicates progressively weakening correlations verbal visual Source: J. R. Gray and P. M. Thomson (2004) Nature, reproduced 41/65 From Snow, et. al. (1984) Life Cycle Pattern of Fluid and Crystallized Intelligence Me 42/65 Life Cycle Earnings by Education and Ability Me Source: L.A. Lillard, “Earnings vs. Human Wealth,” American Economic Review, 1977 43/65 Data from NBER Thorndike, tests designed by one of pioneers of multiple intellingence Cross-Fertilization of Human Capital and Gc/Gf Theory • Biological fixity is implicit in many discussions of intelligence, most notoriously in HerrnsteinMurray’s Bell Curve • Human capital theory allows for ability differences, but primary emphasis is on malleability of human agent and role of choice and incentives in determining skills • Key idea in human capital theory going back to Ben Porath is the human capital production function. 44/65 Human Capital Production Function Ben Porath (1967) Increment to Human Capital in Period t Ability Parameter % Time Spent Learning Stock of Human Capital Purchased Inputs Optimal Life Cycle Pattern of Time Allocation s = 1 during school s<1 on-the-job training during labor market career 1-s time spent earning s declines over career, reaching 0 at retirement 45/65 Relationship to Gf/Gc Theory of Intelligence Learning? Increment to Human Capital in Period t Fluid intelligence? Ability Parameter Crystallized intelligence? % Time Spent Learning Stock of Human Capital Environment? Purchased Inputs human capital is self-productive 46/65 Two Important Qualifications Learning? Increment to Human Capital in Period t Fluid intelligence? Ability Parameter Crystallized intelligence? % Time Spent Learning Stock of Human Capital Environment? Purchased Inputs 1. Heckman and colleagues, in a series of papers, have shown that the sequence of investments matters in early childhood- K t is not homogenous stuff. Creates irreversibility in investments, making remediation difficult 47/65 Cunha-Heckman Model • Proposes human capital technology that goes beyond Ben-Porath in a number of ways – multiple abilities • cognitive (fluid/crystallized) • non-cognitive (motivation, self-discipline, time preference) – self-productive – allows dynamic complementarity • implies that time sequence of investment matters – consistent with variety of empirical evidence on child development Detailed Summary: Cunha and Heckman, “Interpreting the Evidence on Life Cycle Skill Formation,” In Hanushek and Welch, eds. Handbook of the Economics of Education, 2006 48/65 Second Qualification Learning? Increment to Human Capital in Period t Fluid intelligence? Ability Parameter Crystallized intelligence? % Time Spent Learning Stock of Human Capital Environment? Purchased Inputs 2. James Flynn has shown that mean intelligence has risen across cohorts. Suggests average 0 is not a constant in the population. Recently, Flynn and Dickens (2001) suggest gene-environment interaction to account for this. I will argue that their explanation is consistent with theory and evidence from human capital 49/65 The Flynn Effect: Secular Change in IQ (note: there is little cross-cohort change in crystallized intelligence) source: Blair, et. al. (2005) Intelligence 50/65 The Flynn Effect: Secular Change in IQ (note: there is little cross-cohort change in crystallized intelligence) However, many psychologists (including Flynn) increasingly believe a substantial part of this growth may artifactual, due to growing “test-wiseness” source: Blair, et. al. (2005) Intelligence 51/65 “Heritability Estimates Versus Large Environmental Effects: The IQ Paradox Resolved” Dickens and Flynn, Psychological Review (2001) • Cross-cohort growth in IQ is not consistent with hereditarian view nor with plausible environmental change within additive G + E model. • Can resolve paradox within model of GxE interaction in which environments are correlated with genes and amplify genetic effects • Correlation generated by matching of genetic abilities and environments conducive to reinforcement of these abilities. • Show how these interactions can lead to cross-cohort growth in IQ that is consistent with high heritability. 52/65 Human Capital and Gene-Environment Interaction • Human capital theory provides a model, supported by a huge empirical literature, of the kind of environmental amplification of genetic differences of the type hypothesized by Dickens and Flynn • Competitive markets in the presence of a population with heterogeneous abilities leads to a matching of innate ability and training opportunities that amplifies skill differentials • However, human capital is never mentioned in this paper (even though Dickens is an economist) nor is it mentioned elsewhere in the cognitive psychology literature 53/65 Self-Selection Matches Environment and Abilities in Acquisition of Skills – Marriage and Family via Quality/Quantity of Children • Willis (1973), Becker-Lewis (1973), Becker-Tomes (1976) – Formal Schooling, Occupational Choice and On-the-Job Training • Becker (1962), Willis-Rosen (1979) • Rosen (1972), Johnson (1978), Jovanovic (1979) – Migration • Sjastaad (1962) 54/65 Economic Growth and Increasing Cognitive Ability • Striking new element in Dickens-Flynn is endogenous growth in IQ across cohorts, somewhat reminiscent of Fogel’s analysis of secular growth in height • Related theoretical and empirical work in economics by Galor and Moav (2000) and Taber (2001) suggests that economic growth is “ability biased” in the sense the rising return to education, is an increase in the return to ability rather than to college • The Dickens-Flynn argument suggests that the aggregate supply of ability has a positive elasticity in the long run 55/65 “Use it or Lose it?” Retirement and Cognition Does being on the job prevent cognitive decline? “Use or Lose It” Retirement and Cognitive Reserve • The HRS is now being replicated around the world, with the ELSA study in England, the SHARE project in 15 countries in Europe, new studies in Korea, Japan and planned ones in China and India • Availability of cross-nationally comparable data promises to create many new research findings • I will illustrate this promise with some recent research by a Belgian team of economists and psychologists who use the SHARE, ELSA and HRS data to investigate the idea that people can avoid cognitive decline at older ages by being in a more stimulating work environment 57/65 “Use or Lose It” (cont.) • They use a cross-country, cross-sectional analysis to examine the relationship between early retirement for men and cognitive decline between age 50-54 and 60-64 • For each country, they calculate the mean values of Early Retirement = LFPR(60-64)/LFPR(50-54) Cognitive Decline = Cog(60-64)/Cog(50-54) 58/65 Use it or Lose It: Cognitive Reserve Employment rate and cognitive performance Relative difference between 60-64 and 50-54 years old men 0% Cognitive performance (relative difference) Decreasing Cognition United States -5% Denmark Greece Germany Belgium -10% The Netherlands Italy Sweden Switzerland Spain United Kingdom Austria -15% Earlier retirement France -20% -25% -100% -90% -80% -70% -60% -50% -40% -30% -20% -10% 0% Employment rate (relative difference) Source: S. Adam, E. Bonsang, S. Germain and S. Perelman (2007), “Retirement and cognitive reserve: A stochastic frontier approach applied to survey data”, CREPP DP 2007/04, University of Liège. 59/65 Is the Relationship Causal? • Plausibly, yes. – Very strong cross-country relationship between retirement rates and government policy found by Gruber and Wise (1999) – Policy variations are likely to be exogenous to the country-specific average cognitive status of men age 50-54 relative to those age 60-64 60/65 What Will Happen to Retirement for the Early Boomers? (cont.) • Trend toward lower labor force participation at older ages is much sharper in a number of European countries Source: J. Gruber and D. Wise, Social Security Programs and Retirement Around the World, U. Chicago Press, 1999. 61/65 Retirement Policy Shapes Retirement Behavior Percent Early Retirement 70 Belgium France Italy Holland 60 UK 50 Germany Spain Canada 40 US Sweden 30 20 40 60 80 100 Percent Penalty for Continued Work Source: J. Gruber and D. Wise, Social Security and Retirement Around the World (NBER, 2000) 62/65 Recent Cohorts of Americans in HRS Expect to Work Longer Expectations of Working After Age 65 Males and Females Age 51-56 40 42.4 36.4 30 33.0 29.5 24.5 0 10 20 22.7 1992 1998 Male 2004 1992 1998 2004 Female 63/65 Maybe that will be good for their brains as well as their wallets Expectations of Working After Age 65 Males and Females Age 51-56 40 42.4 36.4 30 33.0 29.5 24.5 0 10 20 22.7 1992 1998 Male 2004 1992 1998 2004 Female 64/65 Conclusions • Human capital theory points to the importance of finite, but not fixed cognition • Cognitive economics argues for using new types of data to measure cognition in many dimensions and to understand the mapping between what is in people’s minds and decision making • This will enrich the traditional concerns of human capital theory: – Determining the value of cognition at home and at work – Understanding the market and non-market determinants of the match between cognitive endowments and learning environments – Exploring the demand and supply of cognition in the short and the long run 65/65