File - BBA Group A 2010

advertisement

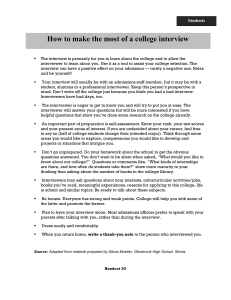

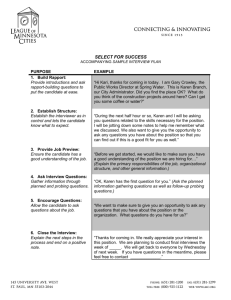

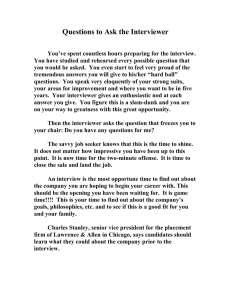

INTERVIEWS GOALS OF THE INTERVIEW Assess the candidate and determine whether there is a good fit between the candidate’s capabilities and the position requirements Describe the job and working conditions Create goodwill for the organization, whether or not the candidate is hired ELEMENTS OF GOOD INTERVIEWING Meeting the interview goals requires the following on the interviewer’s part: Interpersonal skills, which put a job candidate at ease and elicit the most accurate responses. Preparation helps an interviewer cover all job-related questions and avoid saying things that might violate antidiscrimination laws, create an implied employment contract, or misrepresent the job. Objectivity requires the interviewer to be impartial and unbiased. Interviewers must evaluate a candidate based on the factors that predict future job performance. Good recordkeeping supplies the information needed to compare different candidates and documents the screening process in case a rejected candidate challenges the hiring decision. INTERVIEW TYPES STRUCTURED INTERVIEWS The interviewer approaches the interview with an organized and well-planned questioning method while always staying on task. Some interviewers will ask the interview questions in a specific order while others take a more relaxed approach, though still addressing all pre-planned questions. Structured interviews generally provide the interviewer with the information needed to make the hiring decision. All candidates are asked the same questions, rather than tailoring the questions to target a specific individual. UNSTRUCTURED INTERVIEWS Unstructured interviews do not rely upon a prepared agenda. Instead, the candidate sets the pace of the interview. The lack of structure makes it difficult to compare and rank candidates because they do not respond to the same questions. However, unstructured interviews are sometimes used to make the selection between two, equally qualified, candidates. INTERVIEW QUESTIONS Interview questions should accomplish the following goals: Determine a candidate’s qualifications and general character, in relation to the job Expose undesirable traits Clarify information Provide other job-related data Reveal inconsistencies JOB-RELATED QUESTIONS Skills and abilities, including technical skills, communication ability, analytical ability, and specialized training Behavioral factors: motivation, interests, goals, drive and energy, reliability, stress tolerance. Performance is a function of skills and abilities multiplied by behavioral considerations; skills and abilities determine whether someone “can do” a job. Behavior determines whether they “will do” a job. Both must be measured. Corporate culture and job fit issues: team orientation, customer service focus, and accountability, for example. EVALUATING CANDIDATE RESPONSES The interviewer should not feel that a candidate’s first answer to any of the questions must be accepted as the only answer. When the interviewer feels an answer is lacking, the interviewer should ask layered questions until reaching an answer with a satisfactory amount of information. QUESTIONING TECHNIQUES The best interviewers employ a flexible questioning technique to elicit pertinent, accurate information. Employers should vary the questioning technique according to the goals of the interview. For example, an appropriate technique in one instance may yield false, incomplete, or misleading information in another. The best interviewers use some combination of the following techniques as the situation demands. CLOSE-ENDED QUESTIONS Close-ended questions are most commonly asked in interviewing and are the most commonly misused questions. “Can you work under pressure?” Only “Yes” and “No” are the possible answers. A closed-end question also helps interviewers in an attempt to refresh their own memory or in verifying information from earlier in the interviewing sequence: “You were with Company X for 10 years?” OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS Open-ended questions do not lend themselves to monosyllabic answers; instead, the question requires an explanation. “How do you succeed in working under pressure?” BEHAVIORAL QUESTIONS Behavioral questions are based on the premise that past behavior is the best predictor of future performance. “Share with me an experience when . . .” “Give me an example of . . .” NEGATIVE-BALANCE QUESTIONS Interviewers often assume, albeit incorrectly, that a candidate who is strong in one area is equally impressive in all areas. This is not always the case. To avoid this assumption, an interviewer may ask the following questions: “That is very impressive. Could you please describe an occasion when the situation did not work out to your advantage?” “Additionally, please offer an example of an aspect in this area where you struggle.” NEGATIVE CONFIRMATION When interviewers have sought and found negative balance, they may feel content that they are maintaining their objectivity and move on or that an answer they receive may be disturbing enough to warrant negative confirmation. Example ; “That is very interesting. Let’s talk about another time when you had to . . .” REFLEXIVE QUESTIONS Reflexive questions function to close a line of questioning and move the conversation forward. Reflexive questions help interviewers calmly maintain control of the conversation no matter how talkative the interviewee. An interviewer may accomplish this by adding phrases, such as the following, to the end of a statement: Don’t you? Couldn’t you? Wouldn’t you? Didn’t you? Can’t you? Aren’t you? LOADED QUESTIONS Loaded questions are inappropriate as they may lead to manipulation by the interviewer. Loaded questions are fundamentally problematic because questions require the interviewee to decide between equally unsuitable options. For instance, the following is a loaded question: “Which do you think is the lesser evil, embezzlement or forgery?” LEADING QUESTIONS Leading questions allow interviewers to lead the listener toward a specific type of answer. . Leading questions often arise accidentally when the interviewer explains what type of organization the interviewee will be joining. For instance, the interviewer might proudly exclaim, “We’re a fast-growing outfit here, and there is constant pressure to meet deadlines and satisfy our ever-increasing list of customers”, then ask, “How do you handle stress?” QUESTION LAYERING A good question poorly phrased will be ineffectual and provide the interviewer with incomplete or misleading information. For example, when an interviewer wants to determine whether a candidate could work well under pressure the basic line of questioning (“Can you work under pressure?”) may prove to be the wrong approach because the question: requires only a yes or no answer, which fails to provide adequate information for the interviewer leads the interviewee toward the type of answer the individual knows the interviewer wants CONTI….. Instead, interviewers can use a combination of all the questioning styles and techniques to examine the topic from every angle. For example, to examine all angles of a topic the interviewer may ask: Who? What? When? Where? Why? How? CONTI…… The following sequence demonstrates how much more relevant information an interviewer can glean through question layering: Tell me about a time when you worked under pressure. (Open-ended.) So, it was tough to meet the deadline? (Mirror statement.) How did this pressure situation arise? (Question layering.) Who was responsible? (Question layering.) Why was this allowed to occur? (Question layering.) Where did the problem originate? (Question layering.) ADDITIONAL INPUT QUESTIONS Interviewers can use the following techniques to gain more information from an initial question: If the interviewer wants to hear more — whether dissatisfied with the first answer or interested in obtaining more information — the interviewer could say, “Can you provide more detail about that? It’s very interesting,” or, “Can you give me another example?” Perhaps the best technique for gathering more information is for an interviewer to simply sit quietly, while maintaining eye contact with the interviewee and saying nothing. If the conversation lulls, the interviewee may instinctually attempt to fill the silence and provide more information and/or details. Although an interviewer may initially find the silence difficult to manage, patience and allowing the interviewee to speak without encumbrance can be effective. ADDITIONAL QUESTIONS Employers should try to include questions that go beyond a candidate’s technical competence or knowledge. The interviewer should probe for qualities needed to succeed at the job: Organizational skill Willingness to put in the extra time and effort necessary to complete a project RELEVANT AND JOB-RELATED QUESTIONS MIGHT TARGET THE FOLLOWING Incomplete information on application form Work experience or education Gaps in work history Geographic preferences Normal working hours Willingness to travel Reasons for leaving or planning to leave previous job Job-related achievements Signs of initiative and self-management IMPROPER INTERVIEW QUESTIONS Do not solicit information that employers are legally barred from considering in the hiring process. For example, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and similar state laws, hiring decisions cannot be based on an the following: Race Religion Creed Sex, pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions Marital status National origin Ancestry PERSONAL DATA "What is your maiden name?" "Do you own or rent your home?" "What is your age?" "Where do you live?" "What is your date of birth?" "Are you married?" Questions which tend to identify an applicant's age as over 40. EDUCATION The dates of attendance or completion of elementary or high school. CITIZENSHIP Birthplace of applicant or of applicant's parents, spouse or other relative. "Are you a U.S. Citizen?" or "What is your citizenship or that of your parents, spouse or other relative?" Questions as to race, nationality, national origin, or descent. "What is your mother's tongue?" or "What is the language you speak at home?" FAMILY Applicant's marital status. The number or ages of children or dependents. Provisions for child care. Pregnancy, childbearing or birth control. MEDICAL Questions which indicate an applicant's sex. The applicant's height and weight. Applicant's general medical condition, state of health, or illness. Questions regarding HIV, AIDS, and related questions. "Have you ever filed a workers compensation claim?" "Do you have any mental or physical disabilities or handicaps?" ASSOCIATIONS "Have you ever been arrested?" Applicant's credit rating. Ownership of a car. Organizations, clubs, societies or lodges which an applicant belongs to. Religious obligations that would prevent an individual from being available to work on Friday evenings, Saturdays, Sundays or holidays. Asking an applicant the origin of their name. "Do you speak __________________?" (unless a requirement for the job). "Do you have any physical or mental disability/handicap that will require reasonable accommodation?" STRUCTURING THE INTERVIEW In structuring the interview, interviewers may mistakenly use a job candidate’s resumé as a guide for structuring the interview. Generally, the resumé only provides information the candidate wants to reveal. Following the resumé throughout the interviewing process allows the candidate to control the interview, not the interviewer. Interviewers must establish a set structure, to be applied consistently, for each interview to accomplish efficient and accurate interviews. SET THE TONE Interviewers may set the tone of the interview by first greeting the candidate and then engaging the candidate in casual conversation to create a calm and relaxed atmosphere. Comfortable and secure candidates may communicate more honestly. Interviewers may ask about the person’s hobbies, interests, travel, or city of residence. However, interviewers must remember to avoid sensitive areas like children, marital status, or church activities. The formal interview may then begin through a simple transition question, such as, “What do you know about the organization?” or “How did you hear about this job opening?” PROVIDE AN OVERVIEW Interviewers should provide the candidate with an overview of the interview process. For example, how the interview will proceed and what will be covered — job experience, education, interests. DISCUSS WORK EXPERIENCE AND EDUCATION In discussing a candidate’s work experience and education, the interview should ask prepared questions first, following up any responses that deserve further inquiry. CANDIDATE’S INTERESTS AND SELFASSESSMENT After discussing a candidate’s education and work experience, the interview may then ask a few questions about a candidate’s activities and interests to get a broader perspective. Candidates may also be asked to provide a self-assessment, summarizing personal and professional strengths, as well as “developmental needs” or qualities that the individual might want to change or improve. REVIEW THE JOB Interviewers would be wise to not discuss details of the job until the interview has covered a candidate’s qualifications ; otherwise, a candidate may exaggerate certain skills required by the position. An interviewer should review the organization, the job, salary, benefits, location, and any other pertinent data CLOSE THE INTERVIEW In the final portion of the interview, the candidate should be given an opportunity to ask questions about the organization and the job Interviewers should thank the candidate for the time spent on the interview and review the next steps in the hiring process. INTERVIEWING PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES Employers with 15 or more employees must comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The ADA protects persons with disabilities from discrimination in hiring and treatment on the job. CHECKLIST FOR CONDUCTING A HIRING INTERVIEW The person conducting the interview should be well prepared and knowledgeable on the company’s interviewing and hiring practices. When conducting the interview, the interviewer should use the following outline: Establish Rapport Control the Interview Document the Interview CONDUCTING EFFECTIVE MEETINGS What is Meeting? Two or more people come together for the purpose of discussing a (usually) predetermined topic such as business or community event planning, often in a formal setting. WHAT IS MEETING? What is the Purpose of the Meetings? To socialize, network and build relationships To present information that cannot be presented in any other way To obtain input and feedback from people where there will be greater richness of idea through interaction To make decision where the group is truly the decision-maker To celebrate success MEETING MANAGEMENT A set of skills Very expensive activities because the cost of labor for the meeting …. 5 MINUTES FOR PREPARATION 5 MINUTES FOR PRESENTATION WHY MEETING IS IMPORTANT Meetings are important because that is where an organization’s culture and climate perpetuates itself Meetings are one of the ways that an organization tells its workers: “You are a member.” If you have bad, boring, and timewasting meetings, then the people begin to believe that this is a bad and boring company that does not care about time great meetings tell the workers, “This is a GREAT organization to be working for!” Also, remember that bad meetings lead to more bad meetings which cost even more money DO YOU REALLY NEED A MEETING? If you can accomplish your goal without a meeting don't have one” Unnecessary or less than productive meetings are costly and ineffective. Can this be done any other way? o One on one over lunch o A Quick phone call or email Unnecessary meetings can have even worse effects than the waste of money MEETING CAN BE EXPENSIVE Work hours--Calculate combined salaries of attendants + annual overhead + various costs / Working hours per year (2080) After hours--Calculate cost of being away from family or other functions Annual Salaries Annual OverheadCost Total Work Hours per Equals year 240,000 150,000 400 390,400 2080 187.7 Combined Salaries + Overhead + meeting Costs / Work Hours per Year Overhead is equal to company overhead per year. Additional Costs are associated w/ Briefing Rooms, Refreshments, Paper, Equipment and etc. NON-FINANCIAL COST Intangible costs include Missed Time with Family Fuel Bumping Schedules Reaction Time Frustration SOME USEFUL TOOLS Outlook Express Meeting Organizers TYPES OF MEETINGS Annual General Meeting (AGM) Weekly Committee Meeting Monthly Committee Meeting Quarterly Members Meeting Event Planning Meeting - Hallowen Night - Deepavali Celebration - Bowling Inter College Competition DOCUMENTS FOR MEETING Notice of Meeting Previous Meeting Minutes Attachment for Discussion NOTICE OF MEETING AGENDA A list of meeting activities in the order in which they are to be taken up, beginning with the call to order and ending with adjournment. It usually includes one or more specific items of business to be considered/ discussed. DEVELOPING AGENDAS Think of what overall outcome you want from the meeting and what activities need to occur to reach that outcome • Design the agenda and circulate to all participants so that they get involved early by having something for them to do right away and so they come on time. DEVELOPING AGENDAS Ask participants if they’ll commit to the agenda. Keep the agenda posted at all times Do not overly design meetings, be willing to adapt the meeting agenda if members are making progress in the planning process. DEVELOPING AGENDAS Think about how you label an event, so people come in with that mindset. Give participants a chance to understand all proposed major topics – circulate the agenda and previous meeting minutes at least one week before the meeting. EXERCISE 1 1. Form a group of committee consists of President, Secretary and other committee members 2. Develop an agenda on the “Teambuilding Event” – first meeting. OPENING MEETINGS Always start on time; this respects those who showed up on time and reminds late-comers that the scheduling is serious. Welcome attendees and thank them for their time. OPENING MEETINGS Clarify your role (s) in the meeting Review the previous minutes at the beginning of each meeting before further to the agenda TIME MANAGEMENT TIME MANAGEMENT One of the most difficult facilitation tasks is time management – time seems to run out before tasks are completed. Therefore, the biggest challenge is keeping momentum to keep the process moving. You might ask attendees to help you keep track of the time. EVALUATIONS OF MEETING PROCESS It’s amazing how often people will complain about a meeting being a complete waste of time – but, they only say so after the meeting. Get their feedback during the meeting when you can improve the meeting process right away. EVALUATIONS OF MEETING PROCESS Evaluating a meeting only at the end of the meeting is usually too late to do anything about participants’ feedback In a round-table approach, quickly have each participant indicate how they think the meeting is going. EVALUATING THE OVERALL MEETING Leave 5 – 10 minutes at the end of the meeting to evaluate the meeting; don’t skip this portion of the meeting Have each member rank the meeting from 1 – 5, with as the highest and have each member explain their ranking. Evaluating the Overall Meeting Evaluation Areas: 1. Content (Agenda) 2. Time 3. Outcome 4. Efficiency 5. Problem Solving 6. Action CLOSING MEETINGS Always end meetings on time and attempt to end on a positive note. CLOSING MEETINGS At the end of a meeting: 1. Review actions and assignments 2. Set the time for the next meeting (ask each person if they can make it or not – to get their commitment Clarify that meeting minutes and/ or actions will be reported back to members in at most a week (this helps to keep momentum going) MEETING MINUTES 1. 2. 3. 4. Draft the minutes and send to President/ Advisor for verification (5 days) President/ Advisor to verify the minutes before sending to all members (3 days) Circulate the approved minutes to all members Members to feedback on the minutes before the next meeting MEETING MINUTES Minutes should cover four elements: 1. Attendance - What were the date and location? - Who showed up? 2. Decisions - What was the purpose of the meeting? - What decisions were made and why? MEETING MINUTES 3. Responsibility - Who’s taking responsibility to implement the decision? 4. Progress - What progress have the people made who took responsibility toward achieving the decisions made in past meetings? MINUTES OF MEETING Heading Present Attendance Absent Agenda according to the Notice of Meeting Confirmation of the previous meeting minutes as correct Person in-charge MINUTES OF MEETING Any topics that not in the agenda Meeting finish at 6.10pm needs to be recorded Secretary of the meeting to write the minutes of meeting Chairperson of the meeting to vet the minutes of meeting OUTLOOK MEETING ORGANIZER MEETING CHECKLIST Material Resources Meeting worksheets (action plans or barrier & solution worksheets) List of members with phone numbers and addresses for any new members present Name tags for large meetings of new groups Overhead Projector, PowerPoint Projector Directional signage Laptop Computer List of Members Saad Khan Manager HRContact S.No Name 1 Faraz Assit 2 Fahd Faraz 3 Zohaib Kamran Iqbal Finance0342-4652578 Manager Mirza0301-5457644 Manager Admin 0304-4572487 MEETING CHECKLIST Flip Charts Paper, Notepads, Pens Board, Chalk/Markers Sitting Arrangements Podium with microphone Banquets/Refreshments MEETING PLANNER’S CHECKLIST CATEGORY NUMBERS Meeting Rooms Exhibit hall General Session Room Meal Function Room Hospitality Room Other Food & Beverage Breakfast Lunch Hi-Tea Dinner .. Audio/Visual Equipments Flipcharts Microphones & speakers Projection Equipment Pads Pens/Markers Telephone/Internet Other Decoration Banners Banquet set-up Special Signs Printing Agenda forms Participants List Workbook & Handouts Other AMOUNT OUTCOME OF MEETING 1. 2. Establishing a desired outcome provides two things It gives a focus a "benchmark" against which actual outcomes can be measured MEETING PURPOSE Problem-solving meeting To share information Data gathering meeting A decision-making meeting To receive reports To discover, analyze, solve a problem To gain acceptance for an idea or program To resolve a conflict To obtain reactions To gain understanding SELECT THE PARTICIPANTS Who needs to be there? Who will this affect? Should I invite someone just for a fresh perspective? Will the parties work well together? Have you invited the right people? INFORM THE PARTICIPANTS Date, time and place Purpose and desired outcome Information to bring with them What is expected of them at the meeting Meeting length Special arrangements SEND OUT AN AGENDA Written plan for the meeting Order of subjects and time for each “If people are to prepare for a meeting, they need to know what it is about. Let them know. Send out an agenda a few days in advance Keep the agenda simple as possible AL AWWAL MANAGEMENT CONSULTANCY MEETING AGENDA Date: Tues 3rd November 09 Location: Al Awwal House Venue: Conference Hall Timings: 9:00 hrs-12:00 hrs Dept: Human Resources Meeting called by: Faisal Anwar Type of meeting: Monthly Progress meeting Facilitator: Faisal Khan Please Bring: Individual Progress Report Please Read: Time Keeper: Minute Taker: Kamran Saeed Naveed Khan AGENDA ITEMS Agenda Topics Presenter Time allotted Business Overview Faisal Anwar 9:00hrs -10:00 hrs Recruitment services for Mobilink Faraz Mirza 10:00hrs -11:00 hrs Open discussion on business issues All Participants 11:00 hrs-13:00 hrs Attendees: Syed Zohaib,Faisal Anwar,Kamran Iqbal,Saad Khan,Faraz Mirza, Naveed,liaqat,Rizwan WHO DOES WHAT? Facilitator - This is the person designated to direct the group session, by leading members through the activities required to achieve their outcomes. The facilitator ensures all members participate, reviews the outcomes, processes progress and summarizes discussions, decisions and consensus. In most instances the meeting leader retains this responsibility. Timekeeper - One team member should be assigned the task to monitor the agreed-upon time frames for agenda items and give updates to the group on time usage. WHO DOES WHAT? Minute Taker - This person's job is to capture and distribute proceedings of the session, which at a minimum must include "who has agreed to do what, by when." Scribe - Another participant records key ideas and issues, verbatim, on flip charts, and posts them on the meeting room walls for the whole group to see and refer to . ATTENDANCE Make sure everyone attends Send a notice in advance. Include the purpose of the meeting, the list of participants and whom to contact if there are questions Provide agenda in advance Schedule a meeting on a day and time that is convenient to participate START ON TIME “A nine o’clock start means a nine o’clock start Facilitators, don’t start a minute later If you start on time habitually, people will get the message that they must be punctual as well Don’t repeat things for those that arrive late. No need to penalize the many for the tardiness of an attendee or two Latecomers can pick up what they missed from someone after the meeting, or from the meeting minutes” 5 MINUTES FOR PREPARATION 5 MINUTES FOR PRESENTATION OPENING THE MEETING Start on time Welcome the group Establish a friendly atmosphere Set the ground rules: when the meeting will end, how each member will be heard, what is expected Communicate the purpose and desired outcomes to all participants Introduce the situation or problem Stay focused on the agenda topics. Do not wander off topic or become distracted OPENING THE MEETING Bring everyone up to date Open with an attention getter Show that you value their ideas, opinions and questions Record ideas and notes on a flip chart Assign next steps throughout the meeting. Make all next steps specific assignments INTRODUCING THE SITUATION OR PROBLEM How it arose Why it is important Ask how it affects them Point out how they can help Explain the group’s responsibility HANDLING THE MEETING – LEADER QUALITIES Poise Sensitivity Impartiality Tact Sense of Humor Good Judgment Good Listening Skills HANDLING THE MEETING – HOW TO’S Get everyone participating Promote an open atmosphere Summarize Use transitions Ask questions Test possible solutions Keep the discussion on track Work for consensus Plan for future action TIME MANAGEMENT Establish ground rule to make sure the meeting is effective. Ask Attendees to actively participate, to stay focused and to look for closure on discussion whenever possible. This will help to keep the meeting from getting too long and to keep discussion on topic TIME MANAGEMENT If the allocated time for topic is being consistently exceeded, the chair should ask the group for input as to how to resolve the problem Simply build a plan for the session, step by step, and assign times to each step IF IT’S WORTH HAVING, IT’S WORTH RECORDING “Take minutes. They don’t have to be extravagant. Keep it simple While it is best to have an experienced minute taker at each meeting, it is typically a luxury, so more often than not, the responsibility falls on the facilitator. It’s not easy for the facilitator to be effective in both roles, but it can be done IF IT’S WORTH HAVING, IT’S WORTH RECORDING Rotating meeting minute responsibilities among attendees for regularly scheduled meetings can ease the burden on the facilitator” The Minutes should be provided to each participant shortly after the meeting NO GRANDSTANDING PLEASE! “Some (typically manager types), use meetings to show that they are on top of things. They feel absolutely obligated to pipe up to show that they are the boss. Bosses, there is really no need to do this. These attempts to impress typically backfire and actually demonstrate a lack of knowledge. Others use valuable meeting time to try to impress the boss. Try to refrain from doing this as well. The meeting is about getting things done, not about brown-nosing. Offer up your opinions when you think they will truly help accomplish something. Spend the rest of the time listening” CLOSING Review the problem briefly The chair should try to end the meeting on time on a positive note Any action to be taken and assignments resulting from the meeting should be reviewed Indicate time to conclude If there is to be another meeting, the group should agree on the date and time CLOSING Summarize the progress made Mail out notes or action lists as appropriate Follow up with any meeting participant who made a commitment Emphasize agreements Inform of developments Thank the group CONCLUSION Conducting an effective business meeting requires the efforts of all parties involved Careful and diligent planning, written agendas, and prompt and focused conduct will help to ensure that the meeting’s goals are met in an effective manner Determining early in the planning process which participants are necessary and keeping meeting size minimal are also important factors in meeting management ROLE PLAY ROLE PLAY Split into 2 Groups Select the topic for meeting e.g. Cost Control, Discipline, New business developments, Monthly Sales Target review etc.. Plan,Organise,Manage and close the meeting using effective meeting tools and techniques One Group perform and other group evaluate then Vise Versa THE ART OF CONDUCTING EFFECTIVE MEETINGS Name: ACTION BENEFIT TIMINIG REVIEW DATE EDITING AND PROOFREADING STRATEGIES Main Page Editing and proof reading are writing processes different from revising. Editing can involve extensive rewriting of sentences, but it usually focuses on sentences or even smaller elements of the text. Proofreading is the very last step writers go through to be sure that the text is presentable. Proofreading generally involves only minor changes in spelling and punctuation. EDITING STRATEGIES Always Think About Your Target Audience Start with Sentences Consider Words Check Grammatical Details Don't Forget Punctuation and Spelling Try a Sample PROOFREADING STRATEGIES Start with Problem Areas Start with Problem Areas Read from the End to the Beginning Look Just for Typos A Proofreading Checklist Final Advice Try a Sample REPORT WRITING Reports are a highly structured form of writing often following conventions that have been laid down to produce a common format. Structure and convention in written reports stress the process by which the information was gathered as much as the informa- tion itself. DIFFERENT TYPES OF REPORTS Reports vary in their purpose, but all of them will require a formal structure and careful planning, presenting the material in a logical manner using clear and concise language. STAGES IN REPORT WRITING The following stages are involved in writing a report: • clarifying your terms of reference • planning your work • collecting your information • organizing and structuring your information • writing the first draft • checking and re-drafting. TERMS OF REFERENCE The terms of reference of a report are a guiding statement used to define the scope of your investigation. You must be clear from the start what you are being asked to do. You will probably have been given an assignment from your tutor but you may need to discuss this further to find out the precise subject and purpose of the report. Why have you been asked to write it ? Knowing your purpose will help you to communi- cate your information more clearly and will help you to be more selective when collecting your informa- tion. PLANNING YOUR REPORT Careful planning will help you to write a clear, concise and effective report, giving adequate time to each of the developmental stages prior to submis- sion. Consider the report as a whole Break down the task of writing the report into various parts. How much time do you have to write the report? How can this be divided up into the various planning stages? Set yourself deadlines for the various stages. COLLECTING INFORMATION There are a number of questions you need to ask yourself at this stage : What is the information you need ? Where do you find it ? How much do you need ? How shall you collect it ? In what order will you arrange it ? ORGANISING INFORMATION One helpful way of organising your information into topics is to brainstorm your ideas into a ‘spider diagram.’ Write the main theme in the centre of a piece of paper. Write down all the ideas and keywords related to your topic starting from the centre and branching out along lines of connecting ideas. Each idea can be circled or linked by lines as appropriate. When you have finished, highlight any related ideas and then sort topics. Some ideas will form main headings, and others will be sub-sections under these headings. You should then be able to see a pattern emerging and be able to arrange your main headings in a logical order (see diagram below). STRUCTURING YOUR REPORT • • • • • • • • • • . The following common elements can be found in many different reports: Title page Acknowledgements Contents Abstract or summary Introduction Methodology Results or findings Discussion Conclusion and recommendations References Appendices ILLUSTRATION CHECKLIST • Are all your diagrams / illustrations clearly labeled? • Do they all have titles? • Is the link between the text and the diagram clear? • Are the headings precise? • Are the axes of graphs clearly labelled? • Can tables be easily interpreted? • Have you abided by any copyright laws when including illustrations/tables from published documents? LAYOUT Most reports have a progressive numbering system. The most common system is the decimal notation system. The main sections are given single arabic numbers 1, 2, 3 and so on. Sub-sections are given a decimal number - 1.1, 1.2,1.3 and so on. An example structure would look as follows; 1. Introduction 1.1 ———————1.11 ———————1.2 ———————1.21 ———————2. Methodology 2.1 ———————2.11 ———————2.12 ———————- PRESENTATION The following suggestions will help you to produce an easily read report: • Leave wide margins for binding and feedback comments from your tutor. • Paragraphs should be short and concise. • Headings should be clear - highlighted in bold or underlined. • All diagrams and illustrations should be labelled and numbered. • All standard units, measurements and technical terminology should be listed in a glossary of terms at the back of your report. REDRAFTING AND CHECKING Once you have written the first draft of your report you will need to check it through. It is probably sensible to leave it on your desk for a day or so if you have the time. This will make a clear break from the intensive writing period, allowing you to view your work more objectively. Assess your work in the following areas: • Structure • Content • Style Look at the clarity and precision of your work. SUMMARY The skills involved in writing a report will help you to condense and focus information, drawing objec- tive findings from detailed data. The ability to express yourself clearly and succinctly is an important skill and is one that can be greatly enhanced by approaching each report in a planned and focused way. PROPOSAL WRITING The general purpose of any proposal is to persuade the readers o do something, whether it is to persuade a potential customer to purchase goods and/or services, or to persuade your employer to fund a project or to implement a program that you would like to launch. GATHERING BACKGROUND INFORMATION You will require background documentation in three areas: concept, program, and expenses. If all of this information is not readily available to you, determine who will help you gather each type of information. If you are part of a small nonprofit with no staff, a knowledgeable board member will be the logical choice. If you are in a larger agency, there should be program and financial support staff who can help you. Once you know with whom to talk, identify the questions to ask. CONCEPT It is important that you have a good sense of how the project fits with the philosophy and mission of your agency. The need that the proposal is addressing must also be documented. These concepts must be well-articulated in the proposal. Funders want to know that a project reinforces the overall direction of an organization, and they may need to be convinced that the case for the project is compelling. You should collect background data on your organization and on the need to be addressed so that your arguments are well-documented. PROGRAM Here is a check list of the program information you require: the nature of the project and how it will be conducted; the timetable for the project; the anticipated outcomes and how best to evaluate the results; and staffing and volunteer needs, including deployment of existing staff and new hires. EXPENSES You will not be able to pin down all the expenses associated with the project until the program details and timing have been worked out. Thus, the main financial data gathering takes place after the narrative part of the master proposal has been written. COMPONENTS OF A PROPOSAL Executive Summary: umbrella statement of your case and summary of the entire proposal 1 page Statement of Need: why this project is necessary 2 pages Project Description : nuts and bolts of how the project will be implemented and evaluated 3 pages Budget: financial description of the project plus explanatory notes 1 page Organizati on Informatio n: history and governing structure of the nonprofit; its primary activities, audiences, and services 1 page Conclusion : summary of the proposal's main points 2 paragraphs THE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Problem A brief statement of the problem or need your agency has recognized and is prepared to address (one or two paragraphs). Solution A short description of the project, including what will take place and how many people will benefit from the program, how and where it will operate, for how long, and who will staff it (one or two paragraphs). Funding requirements An explanation of the amount of grant money required for the project and what your plans are for funding it in the future (one paragraph). Organization and its expertise A brief statement of the history, purpose, and activities of your agency, emphasizing its capacity to carry out this proposal (one paragraph). THE STATEMENT OF NEED If the grants decision-maker reads beyond the executive summary, you have successfully piqued his or her interest. Your next task is to build on this initial interest in your project by enabling the funder to understand the problem that the project will remedy. You want the need section to be succinct, yet persuasive. Like a good debater, you must assemble all the arguments. Then present them in a logical sequence that will readily convince the reader of their importance. As you marshal your arguments, consider the following six points. First, decide which facts or statistics best support the project Second, give the reader hope Third, decide if you want to put your project forward as a model. Fourth, determine whether it is reasonable to portray the need as acute. You Fifth, decide whether you can demonstrate that your program addresses the need differently or better than other projects that preceded it. Sixth, avoid circular reasoning. THE PROJECT DESCRIPTION This section of your proposal should have five subsections: objectives, methods, staffing/administration, evaluation, and sustainability. the five subsections present an interlocking picture of the total project. OBJECTIVES Objectives are the measurable outcomes of the program. They define your methods. Your objectives must be tangible, specific, concrete, measurable, and achievable in a specified time period. Grantseekers often confuse objectives with goals, which are conceptual and more abstract. For the purpose of illustration, here is the goal of a project with a subsidiary objective METHODS The methods section describes the specific activities that will take place to achieve the objectives. It might be helpful to divide our discussion of methods into the following: how, when, and why. STAFFING/ADMINISTRATION "Staffing" may refer to volunteers or to consultants, as well as to paid staff. Most proposal writers do not develop staffing sections for projects that are primarily volunteer run. Describing tasks that volunteers will undertake, however, can be most helpful to the proposal reader. Such information underscores the value added by the volunteers as well as the costeffectiveness of the project. EVALUATION An evaluation plan should not be considered only after the project is over; it should be built into the project. Including an evaluation plan in your proposal indicates that you take your objectives seriously and want to know how well you have achieved them. There are several types of formal evaluation. One measures the product; others analyze the process and/or strategies you've adopted. Most sound evaluation plans include both qualitative and quantitative data. THE BUDGET The budget for your proposal may be as simple as a one-page statement of projected revenue and expenses. Or your proposal may require a more complex presentation, perhaps including a page on projected support and notes explaining various items of expense or of revenue. SUPPORT AND REVENUE AND STATEMENT For the typical project, no support and revenue statement is necessary. The expense budget represents the amount of grant support required. But if grant support has already been awarded to the project, or if you expect project activities to generate income, a support and revenue statement is the place to provide this information. BUDGET NARRATIVE A narrative portion of the budget is used to explain any unusual line items in the budget and is not always needed. If costs are straightforward and the numbers tell the story clearly, explanations are redundant. ORGANIZATIONAL INFORMATION Normally a resume of your nonprofit organization should come at the end of your proposal. Your natural inclination may be to put this information up front in the document. But it is usually better to sell the need for your project and then your agency's ability to carry it out. LETTER PROPOSAL Sometimes the scale of the project might suggest a small-scale letter format proposal, or the type of request might not require all of the proposal components or the components in the sequence recommended here. The guidelines and policies of individual funders will be your ultimate guide. Many funders today state that they prefer a brief letter proposal; others require that you complete an application form. In any case, you will want to refer to the basic proposal components as provided here to be sure that you have not omitted an element that will support your case. CONCLUSION Every proposal should have a concluding paragraph or two. This is a good place to call attention to the future, after the grant is completed. If appropriate, you should outline some of the follow-up activities that might be undertaken to begin to prepare your funder for your next request. Alternatively, you should state how the project might carry on without further grant support.