Memoir_Storytelling

advertisement

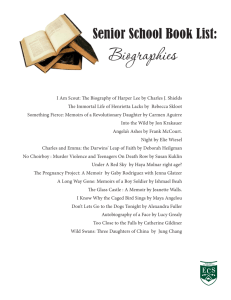

Spalding 1 Professor Spalding 29 December 2008 Making Life Meaningful Memoir. Autobiographical narrative. Storytelling. How does one go about it? I’m not altogether certain that I can tell you how stories are written. All I can do is tell you how I think stories evolve. And I would stress the word evolve. Very often the first telling of a story differs greatly from the later versions, because stories have a tendency to take on lives of their own— lives related to the original circumstances and event, certainly, but distanced from it in context, so that the story must adapt to new contexts and circumstances which require a reinterpretation and revision of the original tale. I well remember an experience once when we were lost on the Paris metro. My father by-passed the correct stop several times and was in a foul temper. My mother made a casual remark which I have never forgotten. “Oh, Chris, please. We’ll be telling this story down the road in a few months and laughing about it.” I suppose that what her words meant to me in that moment were that story does not necessarily reflect reality, but rather that it transforms reality, to the extent that frustration and anger can become mirth, or whatever else you want the story to mean. My grandmother was a storyteller, and I have often heard my father speak of curling up in the small of her back while she told him stories of her childhood. I remember some of those stories myself, and the images she created spring readily to mind—the little girl in the miniature goat-drawn carriage on her way to the general store to buy thread for her grandmother; the girl who searched among the ashes of her large-as-life dollhouse for the remains of her elastic-jointed china doll. Fed on such images, my father became in his own right a storyteller; and so, perhaps, Spalding 2 have I. When teaching students how to write memoir, I often feel inadequate to the task. It is, I think, impossible to tell anyone how memoirs are written. The only way to approach an understanding of memoir is to steep oneself in other people’s memoirs. There are certain techniques that writers use, and they can certainly be pointed out and discussed; but is there truly any way to explain how words cease to be mundane and become magical? To my mind, a story worth telling must pass from the realm of the everyday, and into the realm of myth. In other words, the story takes on a meaning that transcends what actually happened and becomes, instead, a teaching tool, which, when considered quietly and thoughtfully by the listeners, has the power to transform because it situates itself—in some inexplicable way—within the context of their own lives. Someone else’s story becomes personally relevant. Some memoirists refer to this phenomenon as the “universal I,” where the reader somehow becomes the “I” of the story, or at least identifies very closely with the central character. This requires skill on the part of the storyteller, who must decide what to leave in and what to leave out; but it also requires a certain amount of cooperation on the part of the reader or listener, who may just be irritated by the story if he or she is prone to reject advice, however subtly presented. One of the things I tell students in the classroom that actually seems useful is that memoir is classed as “creative non-fiction.” There is, in the world at large, a debate over whether autobiography is truthful when it is discovered that certain elements of the story didn’t happen or were confabulated. The thing about memoir, or about autobiography in general, is that it is related to memory, and memory is not always reliable. One of the great controversies of Hillary Clinton’s campaign for the presidency had to do with her claim that she ran across a foreign runway to escape rifle fire. However, footage of the event shows her very calmly walking across Spalding 3 the runway, surrounded by an entourage. People thought that Senator Clinton had lied; for my own part, I believe that she misremembered, or confused the occasion with another. When I look back over the course of my own life, I find it difficult sometimes to disentangle what happened and when, and I find myself combining memories, reinterpreting memories, and conflating memories. Is this tendency to change what happened necessarily lying? I don’t think so. I tell a story, sometimes, of wanting to set my sister on fire. During the course of the story I talk about marching, can of gasoline in hand, past the Lady Chancellor trees (poinsettias). To be honest with you, I cannot for the life of me remember how old I was, let alone the season of the year— so where does the detail about the poinsettias come from? It has nothing to do with reality; it has everything to do with verisimilitude. It lends credibility to the story, but is hardly central to the tale. I have noticed, in the stories my father tells, a certain tendency to streamline the shape of the story. This detail always gets a laugh, so it stays; this part of the story loses the audience’s attention, so it has to go; to be relevant and to require telling, the story needs to make a point, so it needs revision here and there; this version of the story has everyone sitting on the edge of the seat, so now it will be told this way. And so the story—a random event—evolves from meaningless to meaningful. I think, rather than asking whether or not a story is true, the question we ought to ask is whether it is truthful. Frankly, I do not believe that most of the stories in the Bible are true (at least, in the factual sense). Nor do I believe that truth is the point of most of those stories. However, the stories are certainly truthful. Were Adam and Eve literally individuals who lived in the Garden of Eden? I find it unlikely. If they didn’t exist, what validity does the story of the Fall of Adam have? Simply said, the story is myth. It points out to me that over the course of Spalding 4 life, individuals move from states of innocence to states of experience. In other words, people do things that they ultimately regret. In that sense, all human beings are flawed, as represented in the idea of the first parents in Eden—and so all fall short of God’s expectations. Intrinsically, Man is flawed and in need of redemption. Whether or not the story is true is not my hang-up, although it may be a fundamentalist’s; but for me the story is altogether truthful, which is the real reason it continues to be told. Perhaps the most perplexing thing about scripture is that it does not tend to interpret itself. Most of the Jewish canon seems, at least to me, to provoke thoughtful debate. I often think about the story of Job, whose patience is legendary. In my view, Job was hardly patient at all, and whoever coined the phrase never understood the story. That aside, the story forces a reader to think. What kind of God enters into a bet with the Devil and allows him to toy with a man just to see if he will remain faithful? Is such a God worthy of worship? Are Job’s so-called comforters, in their blind adherence to the tenets of their religion, justified in their faith, and in their accusations against him? Are there times when my own adherence to the rules is as ignorant and stupid as theirs? Would God castigate me for the way I live my religion? Do I have a right to be indignant at the Deity’s behavior? Does my indignation amount to a hill of beans? The story doesn’t answer those questions for us; the story simply allows us to ask the questions, and to draw our own conclusions. I think all good stories do the same thing. The teller relates the tale; but he doesn’t interpret the story. (Fairy tales, for example, never state their purpose. Imagine how ineffective Little Red Riding-Hood would be if it included an explanation.) A good story is replete with sensory detail, with dialogue, and with plot—but it doesn’t cheapen itself with explanation. It is in this respect that many storytellers fail; they are unable to show adequate restraint, and feel a Spalding 5 need to interpret the story. Jesus, when asked why he spoke to the people in parables, gave his disciples an unsettlingly cryptic answer: “Therefore speak I to them in parables: because they seeing see not; and hearing they hear not, neither do they understand. And in them is fulfilled the prophecy of Esaias, which saith, By hearing ye shall hear, and shall not understand; and seeing ye shall see, and shall not perceive” (King James Version of the Bible Matt. 13:13-14). A powerful story opens itself to interpretation and should therefore be experienced rather than explained. For superb examples of memoir, I would recommend Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Walden, Maya Angelou’s “Graduation in Stamps,” Truman Capote’s “A Christmas Memory,” Peter Godwin’s Mukiwa: A White Boy in Africa, Paul Watkins’s Stand Before Your God, and virtually anything by Augusten Burroughs. The first time I read Mukiwa, which is a Rhodesian soldier’s memoir, I was astonished by the minor details he remembered—things I had long since forgotten about: the contents of his ration pack, particular brand names, code words, etc. I marveled that he, an expatriate himself, could recollect such things. Later, as a teacher, I was able to suggest that my students use a method called “sketching,” where they close their eyes and call to mind a place they once knew. Typically, I lead them through an exercise where I recall my parents’ kitchen. I’d arrive home from school, lean my bicycle against the white-washed garage wall, and walk up the back steps. Generally, the top half of the door was already open, so I’d reach over and unlatch the lower half, then walk into the kitchen. In my mind’s eye, I would stand there and survey the room. I remembered that the refrigerator had a logo on it, but in recalling the room during the “sketching” process, I could see the words “Electrolux” on the door, a detail which I had forgotten. After imagining the room, and opening each of the cupboards and the refrigerator, I Spalding 6 would rapidly jot down everything I recalled: my father’s ugly faded yellow water-bottle (which he kept beside the bed at night), the five foil-capped glass milk bottles, the yellow bowl filled with dripping, the strawberry imprinted cereal bowls, the gold-dust dinner service, etc. It is remarkable what a walk through the memory will bring back to mind. Although not all of these details will make it into the story, it is important to populate the mind with actual detail. One thing that each of the above-named memoirs has in common is a richness of sensory detail. It is important, in story-telling, to conjure up images and to include textures and colors, sounds and odors. Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdus, the great pivotal work that stands between the 19th and 20th centuries, begins when an old Jewish homosexual dips a madeleine into a cup of tea and the flavor transports him back to a particular afternoon in his childhood. Who, having read or seen Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles, can forget the scene where Tess slips her letter under the door, or the tragic difference it makes? Sensory details are essential to good story-telling. I sat listening, one morning, to Gregory Maguire’s Wicked, and was captivated by his description of a pond where the children were skating: The villagers had cleared the snow off the center of the pond. It was a ballroom dance floor of silver plate, engraved with the flourishes of a thousand arabesques, mounded round with pillows and bolsters of snow to provide a safe repose for skaters who forgot how to brake or turn. In the fierce sunlight, the mountains looked razor sharp against the blue; great snowy egrets and ice griffons wheeled high above. The ice rink was already noisy with screaming urchins and lurching adolescents (taking every opportunity to tumble and heap each other cozily in suggestive positions). Their elders moved more slowly, processionally around the ice. The crowd fell silent as the household of Kiamo Ko approached, Spalding 7 but, children being children, the silence didn’t last for long. (Maguire 270) The mistake that most novice writers seem to make, when writing their story, is to give a purely narrative account—that is, a blow-by-blow chronology of what took place, from the pregame prayer to the final touchdown. Narrative is essential to every story, but it is brief, no more than the bare bones of a story. Consider the following versions of the same event, and decide for yourselves which is better, the documentary version, or the descriptive one. Here is the documentary version: Evan Berrett came by the office one afternoon. I was very glad to see him. He wanted to know how my dating situation was going. I was, of course, very non-commital. He told me that he was going to set me up with a blind date. I didn’t take him very seriously, but a week later he showed up with two tickets to the international cinema. He said his friend Melanie would be expecting me at 6:00 p.m. on Friday. When I met her, she was kind of funny-looking. Now here is the descriptive version of the same story: In the midst of my research, Evan Berrett showed up at the office one afternoon. I hadn’t seen him since our mission, so I was delighted to see him. He seemed happy and, like all good returned missionaries, was married (and anxious that the rest of us should also tie the knot). When he asked me how the dating scene was going, my response was non-commital. “Oh, come on!” he said. “What are you waiting for? I suppose you think that you’re going to find the one in a bookstore or a library!” He threatened to set me up with a blind date. I didn’t take him terribly seriously, but a week later he showed up with tickets in hand. Spalding 8 “I got you a date,” he said, under the albeit mistaken impression that he was doing me a favor. “Her name is Melanie, and she will be expecting you at 6:00 p.m. on Friday. Don’t let me down. You’re going to see a French movie at the International Cinema.” On Friday night I dutifully showed up at Melanie’s. I rang the doorbell, which was opened by Melanie’s roommate, Barbara Mink [whom I later married, but that’s another story]. When Melanie came to the door I was a little taken aback. She was a thin wisp of a girl, with lank blonde hair. She wore milk-bottle spectacles, and her general pallor was off-set by a tasteless pale-blue neck clasp. There was something about her temples—an almost translucent thinness—which reminded me of the inner membrane which surrounds the yolk and the white of the egg when its shell is missing. Indeed, I rather suspected that had I tapped her forehead lightly with a pencil, our date would have been tragically concluded. Even less appealing was the large mole precariously perched on her upper lip. She was, nevertheless, a pleasant person and an excellent conversationalist. We visited several times beyond the first date and talked for hours. How does one make stories of everyday events? I’m not sure that I am truly qualified to say. However, if pressed to it, my general guidelines would be as follows: Limit your focus. By that, I mean be brief. Choose a particular moment or event and be sure that it makes a definite point. Be certain that it is something other people would relate to, perhaps because it is the kind of experience they may themselves have had; or because it is the kind of experience they might have. Be certain that you enjoy telling the story, and that you toy with it in the re-telling. Be Spalding 9 sure that every word and every detail counts. Leave out what doesn’t need to be said. Include sensory details, and use your words skillfully. Remember, words are like paint, and the storyteller is an artist who creates pictures for his audience. The fat woman at the all-you-caneat champagne brunch at Marie Callender’s isn’t just a fat woman carrying an overloaded plate, she is three-hundred pounds of quivering flesh, whose butt-crack extends above the stretch-waist of her track suit pants, and whose underarms swing while she precariously balances what looks like the Pyramid of Cheops in her right hand. Make the story memorable, so that the point will never be forgotten—but don’t explain the story. Like the incomparable writer of the Book of Jonah, be humorous, or tender, or sincere; but always be believable, so that your audience will want to continue reading (or listening) for what comes next. I’ve always liked foreign film, because the endings are never predictable or necessarily happy, but they always, always make me think. So does good memoir. Spalding 10 Works Cited Holy Bible. King James Version. Maguire, Gregory. Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West. 1993. New York: HarperCollins, 1996. 270-1.