File

James L. Roark ● Michael P. Johnson

Patricia Cline Cohen

●

Sarah Stage

Susan M. Hartmann

The American Promise

A History of the United States

Fifth Edition

CHAPTER 20

Dissent, Depression, and War,

1890-1900

Copyright © 2012 by Bedford/St. Martin's

•

A. The Farmers’ Alliance

I. The Farmers’ Revolt

1. Confronting economic challenges faced a banking system committed to the gold standard; a railroad rate system that was capricious and unfair; and rampant speculation that drove up the price of land.

2. Organizing politically

• as the alliance movement grew, the farmer groups consolidated into two regional alliances with more than 200,000 members: the Northwestern

Farmers’ Alliance and the more radical Southern Farmers’ Alliance.

3. Reaching African Americans

• Southern Farmers’ Alliance worked with the Colored Farmers’ Alliance, an

African American group founded in Texas in the 1880s; attempted to forge a common cause.

4. Appealing to the family

5. Alliance meetings

• picnic, parade, revival, country fair, and political convention; thousands attended Alliance meetings; distributed literature and used lectures to reach out to the illiterate.

6. Farmers’ cooperatives

• Alliance movement stood a series of farmers’ cooperatives that sought to negotiate better prices for their crops; met with stiff opposition from merchants, bankers, wholesalers, and manufacturers, who made it impossible for them to get credit; as the cooperative movement died, the Farmers’ Alliance moved toward direct political action; demanded railroad regulation, laws against land speculation, and currency and credit reform.

•

I. The Farmers’ Revolt

B. The Populist Movement

1. The People’s Party

• advocates of a third party movement had convinced members of the Farmers’ Alliance to form the People’s Party; launched the

Populist movement, which mounted a stinging critique of industrial society.

2. The subtreasury devised the idea of a subtreasury, a plan that would allow farmers to store nonperishable crops in government storehouses until market prices rose.

3. Land reform

• championed a plan to reclaim excessive lands granted to railroads or sold to foreign investors.

4. Currency reform

• endorsed platform planks calling for currency reform in the form of free silver and greenbacks.

5. Empowering the common people

• called for the direct election of senators, the secret ballot, and other electoral issues; also supported the eight-hour day and an end to contract labor; more than just a response to hard times,

Populism presented an alternative vision of American economic democracy.

II. The Labor Wars

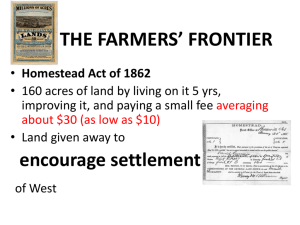

A. The Homestead Lockout

1. Amalgamated Iron and Steel Workers

2. Fort Frick

• Carnegie did not want to be directly involved with the union busting; sailed to

Scotland and left Henry Clay Frick, a tough antilabor man, in charge; Frick erected a fifteen-foot fence around the plant; hired 316 mercenaries from the

Pinkerton Detective Agency to defend what workers dubbed “Fort Frick.”

•

•

3. The lockout and the violence

June 28, Frick locked the workers out of the mills; they immediately rallied to the support of the union and blocked the Pinkertons from entering the plant; gunfire broke out; with more than a dozen Pinkertons and some thirty workers killed or wounded in the scuffle, the Pinkertons retreated to their barges; workers and their families continued to harass the Pinkertons on the barges; when they finally surrendered and came ashore, they were met with verbal and physical violence.

4. Public backlash

• workers took control of the plant; at first, public opinion favored the workers; but the workers’ actions struck at the heart of the capitalist system, pitting workers’ right to their jobs against the rights of private property; yielding to pressure from Frick, the governor of Pennsylvania called out the National Guard to protect Carnegie’s mills; allowed Frick to bring in strikebreakers.

5. Bitter defeat

Alexander Berkman, a Russian immigrant and anarchist, attempted to assassinate Frick; caused public opinion to turn against the workers, even though the Amalgamated and the AFL denounced his action; after four and a half months, the workers capitulated and returned to work to find their wages slashed, their workday lengthened, and 500 jobs eliminated; another forty-five years would pass before steelworkers, unskilled as well as skilled, successfully unionized; after Homestead, Carnegie’s profits tripled.

II. The Labor Wars

B. The Cripple Creek Miners’ Strike of 1894

1. Depression leads to a strike at the mines

• spring of 1893, less than a year after the Homestead lockout, a panic on Wall Street touched off a bitter depression; in the West, silver mines fell on hard times

• when conservative mine owners moved to lengthen the workday from eight to ten hours, the newly formed Western Federation of

Miners (WFM) protested

• some mine owners settled with the union, but others refused; provoked a strike in 1894.

2. Populist support

• striking miners received help from many quarters

• local businesses and grocers sympathized with the strikers

• the county sheriff called for troops to put down the strike, but

Populist governor Davis H. Waite refused, instead serving as arbitrator in the dispute; showed the pivotal power of the state in the nation’s labor wars

• mine owners eventually capitulated, agreeing to an eight-hour workday; but a decade later, mine owners, this time with support from state troops, took back control of the mines; defeated the

WFM and blacklisted all its members.

II. The Labor Wars

C. Eugene V. Debs and the Pullman Strike

1. The model town: Pullman

• company town of Pullman on the outskirts of Chicago, where workers were forced to pay high rents and lived under the constant threat of eviction.

•

2. Wage cuts

• saw their wages slashed five times in 1893, with cuts totaling at least 28 percent, while their rent remained constant; at the heart of the labor problems at Pullman lay not only economic inequity but also the company’s attempt to control the work process; substituted piecework for day wages and undermined skilled craftsworkers.

3. Worker revolt workers rebelled, flocking to the ranks of the American Railway Union (ARU), led by the charismatic

Eugene V. Debs; George Pullman responded to his workers’ grievances by firing three union leaders the day after they led a delegation to protest wage cuts, leading 90 percent of Pullman’s 3,300 workers to strike.

4. A nationwide boycott

• Pullman strikers appealed to the ARU for help and the conflict quickly escalated; ARU membership voted to boycott Pullman cars, and switchmen in other states refused to handle any train carrying

Pullman cars; prompted the General Managers Association (GMA) to recruit strikebreakers and fire protesting switchmen; the boycott/strike spread to more than fifteen railroads and affected twentyseven states and territories.

5. Manipulating the press

• strike remained surprisingly peaceful; however, management distorted and misrepresented the strike; sent out press releases describing the violence supposedly engaged in by the strikers.

6. The government breaks the strike

• Washington, D.C., Attorney General Richard B. Olney, a lawyer with strong ties to the railroad, convinced President Cleveland that federal troops should intervene to protect the U.S. mails (the governor of Illinois saw a peaceful boycott and refused to call out troops); two Chicago judges issued an injunction that prohibited Debs from speaking in public and made the boycott a crime punishable by jail sentence for contempt of court; strategy worked; Cleveland called out the army, Debs was jailed, and in the resulting violence, the strike was broken; Pullman hired new workers to replace many of the strikers; Pullman strike demonstrated that workers had little recourse when the government and courts sided with industrialists in defense of property rights.

III. Women’s Activism

A. Frances Willard and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union

1. Temperance politics

2. Willard’s tactics

• Willard radically changed the direction of the WCTU; moved it away from religiously oriented programs to a campaign that stressed alcoholism as a disease rather than a sin and poverty as a cause rather than a result of drink; joined with labor unions to press for better working conditions for women workers.

•

3. Mobilizing women around a women’s issue

Willard argued that women needed the vote to protect home and family. Willard worked to create a broad reform coalition in the 1890s, embracing the Knights of Labor, the People’s Party, and the

Prohibition Party; WCTU had over 200,000 members in the 1890s; gave women valuable experience in political action.

B. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and the Movement for Woman Suffrage

1. Division and reconciliation

• Stanton and Anthony launched the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869, demanding the vote for women; a more conservative group, the American Woman Suffrage Association, formed the same year, believed that women should vote in local but not national elections; by 1890, the split had healed, and the newly united National American Woman Suffrage Association launched campaigns at the state level to gain the vote for women.

2. New era for women’s rights movement

• won victories in Colorado in 1893, as well as Idaho and Utah in 1896; although it would take another two decades for all women to gain the vote with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, the unification of the two woman suffrage groups in 1890 signaled a new era in women’s fight for the vote.

IV. Depression Politics

A. Coxey’s Army

1. Unemployed march to Washington

• spring of 1894, masses of unemployed Americans marched to

Washington, D.C., to call attention to their economic plight and to urge Congress to enact a public works program to end unemployment

• Jacob S. Coxey from Massilon, Ohio, led the most publicized contingent

• Coxey’s “army” started in Ohio with one hundred men, swelling as it marched east through the Allegheny Mountains

• on May 1, Coxey’s army arrived in Washington and defiantly marched onto the Capitol grounds; they were met by police using nightsticks; Coxey was jailed for his efforts, and by August, the leaderless, tattered armies of the unemployed dissolved.

2. Plight of the unemployed

• Coxey’s army brought attention to the plight of the unemployed; though unsuccessful in forcing federal relief legislation, it called into question the underlying values of the new industrial order; demonstrated how ordinary citizens turned to means outside the regular party system to influence politics in the 1890s.

IV. Depression Politics

B. The People’s Party and the Election of 1896

1. Threat to party unity

• captured more than a million votes in the presidential election of 1892, a respectable showing for a new party; but sectional and racial animosities threatened party unity, especially Populists’ willingness to form common cause with black farmers, which made them hated in the white South.

2. Cries for reform

• Republicans nominated Ohio governor William McKinley on a platform pledging the preservation of the gold standard, western advocates of free silver representing miners and farmers walked out of the convention; open rebellion also split the Democratic Party as vast segments in the West and South repudiated President Grover Cleveland because of his support for gold.

3. Nominating Bryan

• spirit of revolt animated the Democratic National Convention as thirty-six-year-old William Jennings

Bryan whipped the crowds into a frenzy with his “Cross of Gold” speech, a passionate call for free silver; the People’s Party met a week later, and many western Populists urged the party to ally with the

Democrats and endorse Bryan; but the Democrats’ vice presidential candidate, Arthur M. Sewall, a railroad director and bank president, posed significant obstacles to Populists who advocated fusion with the Democrats; to deal with the issue of fusion, the People’s Party convention selected the vice presidential candidate, Tom Watson of Georgia, before selecting the presidential candidate; nomination of Watson undercut opposition to Bryan’s candidacy, and the fusionists triumphed when the People’s

Party convention nominated Bryan for president.

4. A fierce election -

Bryan delivered more than six hundred campaign speeches in 3 months.

5. Sectional divisions

• silver states of the Rocky Mountains lined up for Bryan, while the Northeast stood solidly for McKinley; much of the South, with the exception of the border states, abandoned the Populists and returned to the Democratic fold; midwestern farmers, less receptive to the call for free silver, and eastern workers, who would not gain many benefits from the inflation that free silver would bring, did not rally behind

Bryan, costing him crucial votes.

•

6. Populist agenda

McKinley won twenty-three states and 271 electoral votes to Bryan’s twenty-two states and 176 electoral votes; biggest losers in the election of 1896 turned out to be the Populists; the People’s Party was crushed, and with it died the agrarian revolt, but Populism nevertheless set the domestic political agenda for the United States in the next decades; highlighted issues such as banking and currency reform, electoral reform, and an enlarged role for the federal government in the economy.

V. The United States and the World

A. Markets and Missionaries

1. Economy and expansion-looked abroad

2. Religious zeal

3. The Boxer Rebellion missionary activity and Western enterprise touched off a series of antiforeign uprisings in China that culminated in the Boxer uprising of 1900; Boxers terrorized missionaries and Christian converts throughout northern China; in August 1900, 2,500 U.S. troops joined an international force sent to rescue foreigners besieged in Beijing; put down the rebellion the following year; in the aftermath of the Boxer uprising, missionaries voiced no concern at the paradox of bringing

Christianity to China at gunpoint.

B. The Monroe Doctrine and the Open Door Policy

1. Protecting American hegemony

• the Monroe Doctrine and Open Door policy; American diplomacy worked to buttress the

Monroe Doctrine’s assertion of American hegemony in the Western Hemisphere.

2. American business in Central America

• risked war with Great Britain over America’s role in a conflict between Venezuela and British

Guiana; in Central America, American business triumphed in a bloodless takeover that saw

French and British interests routed by behemoths such as the United Fruit Company of

Boston.

3. The U.S. in the Far East

4. An open door to China

• Secretary of State John Hay wrote a series of notes to Britain, Germany, Russia, France,

Japan, and Italy, calling for an “open door” policy; would ensure access to all and maintain

Chinese sovereignty; by insisting on the Open Door policy, the United States secured access to Chinese markets, expanding its economic power while avoiding the problems of maintaining a far-flung colonial empire on the mainland of Asia.

V. The United States and the World

C. “A Splendid Little War”

1. The Cuban rebellion

2. Yellow journalism

• Journalism—Newspapers fueled public outcry at Spain; circulation war raged in New York

City between William Randolph Hearst’s Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s World; sensational stories called yellow journalism, named for the colored ink used in a popular comic strip.

3. Economic and territorial Interests

• American business had more than $50 million invested in Cuban sugar; American trade with Cuba, a brisk $100 million a year before the rebellion, had dropped to near zero; to expansionists such as Theodore Roosevelt, more than Cuban independence was at stake, because war with Spain opened up the prospect of expansion into Asia as well—Spain controlled not only Cuba and Puerto Rico but also Guam and the Philippine Islands.

4. The Maine

• McKinley slowly moved toward intervention; in a show of American force, he dispatched the armored cruiser Maine to Cuba; a mysterious blast destroyed the ship, killing 267 crew members and prompting cries for war back home.

5. A brief war in Cuba

• declared war in April, and five days after McKinley signed the war resolution, the U.S.

Navy, under Commodore George Dewey, destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay; war in Cuba ended almost as quickly as it began.

6. Roosevelt’s Rough Riders

• Theodore Roosevelt a bona fide war hero; he formed the Rough Riders, a regiment composed of Ivy League polo players and western cowboys; played a role in the decisive battle of San Juan Hill; brought Roosevelt to the attention of prominent independent

Republicans.

V. The United States and the World

•

D. The Debate over American Imperialism

1. The American empire

the American people found themselves in possession of an empire stretching halfway around the globe, including

Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines.

•

2. The fate of Cuba

• the United States directed the writing of a new constitution in 1900; included the so-called Platt Amendment, which granted the United States the right to intervene in Cuban affairs, oversee Cuban debt, and keep a naval base at

Guantánamo.

3. The Treaty of Paris and war in the Philippines

formal Treaty of Paris that ended the war with Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States along with Spain’s former colonies in Puerto Rico and Guam; Filipino revolutionaries bitterly fought American troops, engaging the United States in a nasty guerrilla war that lasted seven years.

4. The politics of imperialism