CUSP Steps: An Overview

advertisement

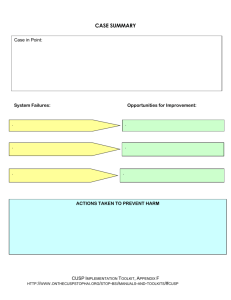

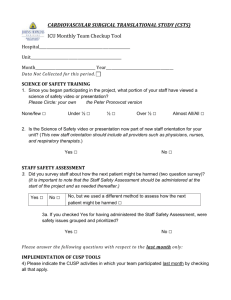

CUSP for Ventilator Associated Pneumonia (VAP) Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 CUSP is Local ............................................................................................................................... 3 How Does CUSP Change Local Culture?.................................................................. 4 CUSP Steps: An Overview ........................................................................................................... 4 Who is Accountable for CUSP? ............................................................................... 5 Pre-CUSP Work ........................................................................................................................... 5 Assemble a CUSP Team........................................................................................... 5 Assess your Culture of Safety (Baseline Assessment) ............................................ 6 CUSP Steps .................................................................................................................................. 7 Step 1: Science of Safety Training ........................................................................... 7 Step 2: Staff Identify Defects .................................................................................. 8 Step 3: Senior Executive Partnership ................................................................... 10 Step 4: Learning from Defects through Collective Sensemaking ......................... 11 Step 5: Use Tools to Improve ............................................................................... 12 CUSP is an Ongoing Process, Not an Endpoint ......................................................................... 14 Getting Help .............................................................................................................................. 14 Appendices................................................................................................................................ 15 References ................................................................................................................................ 17 Introduction Healthcare organizations around the world are increasingly focused on patient safety and healthcare quality. While healthcare providers are committed to improvement efforts, many struggle to create and sustain positive change. The Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program (CUSP) helps providers achieve the lasting improvements they seek. You can redesign your care system through technical and adaptive work to improve patient safety and eliminate preventable harm. Technical work changes procedural aspects of care that can be explicitly defined, such as the evidence to support a specific intervention or the definition for a VAP. Adaptive work changes the attitudes, values, beliefs and behaviors of the people who deliver care and determine whether patients receive the best available evidence-based care. Adaptive work can be discouraging and nebulous. Creating a protocol for elevating the head of the bed is far easier than managing staff’s attitudes and values, or engaging staff to use the protocol. You may be tempted to focus on technical work, and leave complex adaptive problems unaddressed. Yet many change efforts fail because adaptive work is neglected: An evidence-based protocol or checklist (technical work) will only impact outcomes if staff understand, value, and prioritize use of the checklist (adaptive work). The five steps of CUSP bring adaptive work into the change process and help your team improve your unit’s safety culture. By integrating CUSP with technical interventions, your team can achieve real and sustainable improvements in safety. The CUSP Toolkit in practice In 2004, more than 100 intensive care units in the State of Michigan implemented CUSP in their celebrated work to eliminate central line-associated bloodstream infections and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Since their success, thousands of units nationwide have used CUSP to target a wide range of safety problems: patient falls, hospital-acquired infections, medication administration errors, among others.1-8 Check out the list of references to learn more. CUSP is Local CUSP is perhaps the only intervention that has improved teamwork and safety culture on a large scale. Largescale change is achieved when multiple teams implement CUSP locally. Patient safety culture improvement at the local unit-level is crucial. Local norms have a powerful influence on the attitudes and behavior of care providers. Unit culture influences the extent to which providers participate in quality improvement efforts, adhere to evidence-based guidelines, or even speak up when they are concerned about the care of a patient. How Does CUSP Change Local Culture? Frontline providers cultivate wisdom by delivering care within their local systems. They encounter patient safety hazards on every shift and develop tactics to safeguard their patients against them. CUSP helps your team improve local safety culture by tapping frontline wisdom. It provides a mechanism to change systems and eliminate safety hazards for all patients. Far too often, frontline staff members feel like patient safety improvement efforts are done to them instead of done with them. When frontline providers own the improvement process, local safety culture improves. CUSP Steps: An Overview Though CUSP is comprised of five steps, the program is a continuous process designed to incorporate an evidence-based patient safety infrastructure into your unit. The steps are briefly described below: Step 1: Science of Safety Training Introduce your teams to the principles that promote and support patient safety and quality. Help them develop lenses to focus on system factors that can negatively impact care and lead to preventable harm. Step 2: Staff Identify Defects Identify patient safety defects in your work area. Your team can identify defects from incident reports, liability claims, or sentinel events. In this step, ask frontline staff how the next patient will be harmed through a short written survey. Step 3: Executive Partnership In this step, you’ll partner with a senior hospital executive to develop a shared understanding of local defects, build consensus and a plan for how to mitigate those defects, and develop shared accountability for implementing and evaluating the plan. Step 4: Learning from Defects through Collective Sensemaking Your teams will use a practical and valid tool to learn from defects, answering four basic questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. What happened? Why did it happen? What did you do to reduce risk? How do you know that risks were reduced? Step 5: Tools to Improve Use tools to improve teamwork and communication in the your unit. Teamwork and communication tools include Daily Goals, and tools from the national TeamSTEPPS program. Who is Accountable for CUSP? CUSP is a transdisciplinary process that incorporates the wisdom and unique perspectives of all providers and staff. However, in order to ensure timely completion of project activities, your team will need to choose a team leader. This leader will oversee the implementation of CUSP, and additional team members can help implement each of the steps. Pre-CUSP Work Assemble a CUSP Team The CUSP team transcends discipline silos. Transdisciplinary teams collaborate throughout the entire problem solving process, instead of developing solutions in isolation and then trying to align them. The CUSP team includes your team leader, a physician champion, a nurse champion, and a respiratory therapist champion. The CUSP team leader and transdisciplinary project champions must be able to dedicate time to this project. While the exact amount of time required will vary, we suggest a minimum of 2-4 hours per week to this program. Additionally, hospital epidemiology or infection control professionals are important CUSP team members, since they will contribute important expert advice and help with data collection for the project. Your CUSP team will be most effective if it includes frontline staff from across the intensive care unit. The CUSP team leader (or designee) should work with hospital management to connect with a senior executive, and secure his or her commitment to the CUSP program. When selecting a senior executive, ensure he or she is available to contribute meaningfully to the team and is approachable. Whether he or she has experience as a clinician or not, your senior executive partner should be comfortable having important discussions about difficult and sensitive topics. Tools you can use How you’ll use them CUSP for VAP Team Membership Form (Appendix A) List team member names and contact information in this form. Post the list in a visible location for staff reference. CUSP for VAP Team Roles and Responsibilities Form (Appendix B) Clarify mutual expectations for CUSP team members Our quality improvement department has worked on ICU improvement efforts for years. At first, we didn’t understand why our hospital CEO had signed us up for CUSP for VAP. We thought, “We are already doing this stuff.” After joining a few project calls, we began to understand that CUSP would require a different type of quality team that included frontline staff and administrators, and a fundamental restructuring of how our hospital did quality work. – CUSP for VAP Physician Champion How do you get physician buy-in and protected time? Join the conversation at the CUSP for VAP social networking site. https://armstrongresearch.hopkinsmedicine.org/vap.aspx Assess your Culture of Safety (Baseline Assessment) The ongoing measurement of safety culture using surveys or questionnaires is quickly becoming an industry norm in healthcare. If your organization has not conducted a safety culture survey, such as the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety (HSOPS), it should be done in your unit at the outset of this project. Safety culture questionnaires elicit frontline providers’ attitudes and perceptions about patient safety topics. Individual providers complete the questionnaire anonymously, and responses can be reported by job category (for example, nurse, physician, or respiratory therapist, etc.), by unit, or by hospital. Your team can reassess clinical area safety culture every year or so. Before administering a safety culture survey, explain its purpose to frontline providers. Emphasize that you want to tap into their wisdom, opinions, and perceptions of safety on their unit, and ensure that they will receive feedback on the results. All clinical and nonclinical providers who work in your ICU should be included in this culture assessment (for example, nurses, physicians, respiratory therapists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, and unit clerks). Tools you can use How you’ll use them HSOPS Manual 1: Planning and preparing for your survey Learn how to plan and administer your survey, and make use of the important data you collect. Quick Guide: HSOPS CoordinatorRoles and Responsibilities Find the HSOPS Coordinator who’s right for your project team. Quick Guide: Template Debriefing Plan Now that you’ve collected data, making it actionable is the important next step. A good debriefing plan will help. This template provides some important tips. We measure safety culture across the hospital every year, but when CUSP for VAP started, we saw an opportunity to really assess our ICU culture. Even though our staff is tired of taking surveys, we administered HSOPS through the online project platform. This time, we shared survey results and their interpretation with our staff. We told them that we needed their leadership to make things better. Our frontline started to realize that they were the center of our quality team. — ICU Nurse manager, CUSP for VAP Team Member How do you optimize HSOPS response rates and use your culture data? Join the conversation at the CUSP for VAP social networking site. https://armstrongresearch.hopkinsmedicine.org/vap.aspx CUSP Steps Step 1: Science of Safety Training A “system” is a set of parts interacting to achieve a common goal. All too often we assume that patient harm occurs because of inexperience, lack of supervision, or bad luck, when in fact care is delivered in imperfect systems. Clinical area teams must understand the system in which they work to enable change in their clinical setting. Rather than being the main instigators of an accident, operators tend to be the inheritors of system defects…their part is that of adding the final garnish to a lethal brew that has been long in the cooking. James Reason, Human Error What the CUSP team needs to do Have your staff view the Science of Safety video featuring Dr. Peter Pronovost. The CUSP team leader should ensure that all clinicians and staff members watch the Science of Safety presentation within the first month of CUSP implementation. Your CUSP champions can facilitate training for their respective disciplines. Training can be done in large groups, several smaller groups, or during individual sessions depending on what is practical for your clinical area. Tools you can use The Science of Safety Video (Watch the video) How you’ll use them This video will help your teams to: Science of Safety Training Attendance Sheet (Appendix C) Identify system failures that can impact patient safety Apply design approaches that can be used to improve patient safety and quality. Make CUSP steps an integral part of unit processes This form will help you track training completion When we introduced this project to our unit, clinicians were quick to blame each other for our VAP rates. The nurses blamed the doctors; the doctors blamed the nurses and respiratory therapists. We had to teach our staff that infection rates are the result of faulty systems, not bad clinicians. Our VAP rate is not going to budge if all we do is exchange blame. After the Science of Safety training, you could see a few lights go on. It’s definitely a journey, though. Clinicians take care so personally. – CUSP for VAP Nurse Champion How do you train your entire clinical area staff? Join the conversation at the CUSP for VAP social networking site. https://armstrongresearch.hopkinsmedicine.org/vap.aspx Step 2: Staff Identify Defects Frontline providers understand patient safety risks in their clinical areas and have great insight into potential solutions to these problems. Your team needs to tap into frontline providers’ knowledge and use it to guide your safety improvement efforts. The Staff Safety Assessment helps you access this wisdom by directly asking providers: How will the next patient be harmed in your unit? What do you think can be done to prevent this harm? How will the next patient develop a ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) on your unit? What do you think can be done to prevent this VAP? One of the strongest determinants of safety culture is whether local and hospital leadership respond to staff patient safety concerns. Therefore, it is important to follow up on the defects identified by your staff. What the CUSP team needs to do The CUSP team leader (or designee) should hand out a Staff Safety Assessment (SSA) form to all clinical and nonclinical providers in the unit. Timing: We strongly recommend that you hand out the Staff Safety Assessment form at the end of the Science of Safety training session. Logistics: One person should be assigned the task of handing out and collecting the safety assessment forms. To encourage staff to report safety concerns, it may work well to establish a collection box or envelope in an accessible location where completed forms can be dropped off. Collective Sensemaking: Group SSA responses by commonly identified defects (such as communication, medication process, equipment failure, supplies, etc.) and summarize defects (i.e., what percent of total responses were related to communication?). What comes first? Prioritize identified defects using the following criteria: Likelihood of the defect harming the patient Severity of harm the defect causes How commonly the defect occurs Likelihood that the defect can be prevented in daily work A tool you can use Staff Safety Assessment (Appendix D) How you’ll use it Gauge perceptions of risks in your unit and tap into team wisdom to proactively identify improvement targets Our compliance rates for oral care were great. However, when we reviewed our SSA data, we were surprised that so many staff were concerned about compliance. Their comments pointed out that surveillance using the EMR doesn’t work for this particular measure. Through the SSA we discovered that this part of care can be copied forward with several other care activities, and this is often done. However, because this is part of a ‘chunk’ of care activities, the care may not have been completed. As we had already changed to the tear off kits, staff were able to see that oftentimes not all kits were used at the end of the day and they were concerned that some patients were not receiving the care they should. This issue of carrying forward tasks had previously been brought up by staff and we didn’t act on it It became clear that we should have been listening.. – Quality Improvement Officer, CUSP for VAP Team Member How do you get honest feedback about patient harm? Join the conversation at the CUSP for VAP social networking site. https://armstrongresearch.hopkinsmedicine.org/vap.aspx Step 3: Senior Executive Partnership The senior executive and frontline staff partnership are crucial to the CUSP team’s success. These partners hold each other accountable for reducing risk to patients. At the unit-level, the senior executive stimulates discussions about safety, helps prioritize and solve safety concerns, and helps set goals for the clinical area. At the hospital-level, the senior executive may lobby for policy change, promote access to resources, or resolve inter-departmental issues. Additionally, the senior executive is a bridge to the hospital’s C-suite (CEO, CMO, CFO, etc.), and helps to share local wisdom with hospital administration and management. What the CUSP team needs to do The CUSP team leader (or designee) should schedule hour-long monthly safety rounds with the senior executive. He or she should also prepare the senior executive for meaningful participation in safety rounds. If the senior executive does not have a clinical background, offer a tour of your unit. Schedule time with your senior executive to discuss unit-specific information. Include in this information packet: 1. Safety culture survey results 2. The prioritized list of safety issues compiled from the Staff Safety Assessment 3. Pertinent information about the unit that the senior executive may not know (for example, staff turnover rate, compliance with process and policy measures and VAP rate). Executive Safety Rounds Executive safety rounds may begin with a senior executive walk-through of the clinical area, led by a frontline clinician. The focus of executive safety rounds, however, is collaboration between the senior executive, CUSP team, and frontline providers to address safety issues. Your team can solicit collaboration with sit-down discussions that are open to all staff. Review identified safety issues together. The senior executive can help prioritize your unit’s safety concerns. You can use quantitative (for example, numerically rating risk of harm) or informal (for example, discussion until group consensus) methods to prioritize the greatest risks. Informal methods tend to be less burdensome and can accurately reflect unit level risks. Tools you can use Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff Template (Appendix E) How you’ll use them That first meeting’s very important for engaging your senior executive. You can use this template for suggested activities and talking points. Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff Template (Appendix E) That first meeting’s very important for engaging your senior executive. You can use this template for suggested activities and talking points. Safety Issues Worksheet for Senior Executive Partnership (Appendix F) (or a tracking log of your choice) A worksheet you can use for listing and prioritizing risks you’ve identified. Our VAP rates have definitely not been zero. During our CUSP meeting, we discussed the possibility of changing over to the sub glottic endotracheal tubes as our next step to reduce our rates. Our executive was concerned about the additional cost per tube and how that would affect the bottom line. We shared the literature we were given by the CUSP for VAP: EVAP group regarding the cost savings associated with their use. He was impressed and decided to support us in this endeavor. Next step? Convince the rest of the physicians that the tubes are a good idea and that we need them to help us prevent VAP in our ICU.. – CUSP for VAP Team Leader How do you engage your senior executive? Join the conversation at the CUSP for VAP social networking site. https://armstrongresearch.hopkinsmedicine.org/vap.aspx Step 4: Learning from Defects through Collective Sensemaking Once defects are identified and prioritized, the CUSP team must learn from them and implement improvement efforts. The Learning from Defects through Sensemaking (LFD) worksheet (Appendix G) helps frontline providers investigate safety defects: It guides CUSP teams through a structured process to answer four questions: 1. 2. 3. 4. What happened? Why did it happen? What did you do to reduce risk? How do you know that risks were reduced? What the CUSP team needs to do Take a defect identified in your clinical area: an incident report, sentinel event, liability claim, or defect identified from the Staff Safety Assessment; and complete the LFD worksheet. You may want to start with ‘low hanging fruit’ and progress to more difficult problems as you gain experience with the LFD process. After you are comfortable using and explaining the LFD process, you should discuss your LFD projects during executive safety rounds. A tool you can use How you’ll use it Learning from Defects through Collective Sensemaking Worksheet (Appendix G) Use this tool to lead discussions that engage frontline staff in characterizing defects, uncovering system-level causes, and developing plans for improving patient safety and quality. We recommend learning from at least one defect a quarter. We purchased the subglottic endotracheal tubes and placed them in the ICU, rapid response team cart, the ED and the OR. We worked with the appropriate departmental heads and presented at Grand Rounds to assure that providers understood the change, the reasons for the change and to answer any questions. We thought we had covered all our bases. However, patients kept arriving from both the ED and OR with standard tubes. It was time to come up with a solution that worked. We invited representatives the directors from the departments of surgery and anesthesiology to our next monthly CUSP meeting. We used the Learning From Defects through Sensemaking at that meeting to determine the issue and to develop a solution. The surgeons and anesthesiologists felt that the tubes were too big and regardless of that, the expense too high if the patient would be extubated within 24 hours of surgery as planned. Through this process we decided to work with the stakeholders develop an algorithm to help determine which patients are more likely to need longer term intubation. We have already gone through several iterations of the algorithm, but everyone seems to feel that they have been heard and fewer patients are admitted to the unit with a normal ETT. It wasn’t easy to develop the algorithm and it is still being honed to meet the needs of the different stakeholders, but we are making strides in bringing this important intervention to our patients -- CUSP for VAP Senior Executive How do you develop and evaluate your intervention? Join the conversation at the CUSP for VAP social networking site. https://armstrongresearch.hopkinsmedicine.org/vap.aspx Step 5: Use Tools to Improve Throughout this document, we’ve identified tools you can use as you implement CUSP for VAP. In this section, we’ve listed some additional practical tools to help your team improve communication and teamwork. You can find them, and others, in the CUSP Toolkit on the CUSP for VAP project website. Each tool comes with detailed instructions. What the CUSP team needs to do Review your safety culture scores and determine which areas need improvement (for example, poor teamwork climate). Collaborate with frontline providers to select a tool that best addresses their concerns. More tools you can use How you’ll use them Daily Goals Improve team communication and role clarity while caring for a patient in the ICU. When to use? This tool should be used with every patient. Research shows it can make a big difference when used in a meaningful way. AM Briefing Tool Improve team communication regarding clinical area workflow with this tool. When to use? When staff believe that ICU workflow and communication are poorly-coordinated Shadowing Another Professional Identify and improve communication, collaboration & teamwork skills between different disciplines When to use? When ICU staff members believe that disciplines need to walk a mile in each other’s shoes. After a few project gains, we realized that we could tap frontline wisdom every morning by implementing the Daily Goals sheets. Now, as each case is discussed during rounds, a plan is developed for that patient’s care for that day. The goals can involve everything from ordering an MRI to decreasing pain meds, to performing an SAT. Goals are discussed with all staff present and documented. The documentation allows staff not present during rounds to help their patients progress. We have found that Daily Goals are very effective for the night shift. They essentially have a status check for the morning and directions on how to proceed for the night. We are not just ‘implementing CUSP’; we are building a patient safety infrastructure. -- CUSP for VAP Physician Champion How do you optimize Daily Goals? Join the conversation at the CUSP for VAP social networking site. https://armstrongresearch.hopkinsmedicine.org/vap.aspx CUSP is an Ongoing Process, Not an Endpoint CUSP is an ongoing process, and is never truly finished. For example, it will be helpful to have a process to ensure that new frontline providers, who join the unit after CUSP is underway, watch the Science of Safety video. One strategy is to include the Science of Safety presentation in their orientation. Additionally, though staff complete the Staff Safety Assessment in the second step of CUSP, you may consider completing the Staff Safety Assessment on a periodic basis (e.g., quarterly) or keep the forms readily available for staff to complete when they identify a patient safety risk. Getting Help We recognize that CUSP represents a lot of new material. You can access more learning materials, such as recorded project calls and slide sets, on the CUSP for VAP Project website (https://armstrongresearch.hopkinsmedicine.org/vap/vap.aspx). If you have additional questions, please post them to the CUSP for VAP Project social network or email us at CUSPEVAP@jhmi.edu. Appendices Appendix A CUSP for VAP Team Membership Form. Appendix B CUSP for VAP Team Roles and Responsibilities Form. Appendix C Science of Safety Training Attendance Sheet Appendix D Staff Safety Assessment Appendix E Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff Template Appendix F Safety Issues Worksheet for Senior Executive Partnership Appendix G Learning from Defects through Collective Sensemaking Tool Appendix H CUSP for VAP Daily Goals Appendix I Shadowing Another Professional Appendix J Briefing Tool. Appendix K Observing Rounds Tool Appendix L Barrier Identification and Mitigation Tool References 1. Berenholtz SM, Pham JC, Thompson DA, Needham DM, Lubomski LH, Hyzy RC, Welsh R, Cosgrove SE, Sexton JB, Colantuoni E, et al. Collaborative cohort study of an intervention to reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia in the intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011 Apr;32(4):305-14. 2. Cooper M, Makary MA. A comprehensive unit-based safety program (CUSP) in surgery: Improving quality through transparency. Surg Clin North Am 2012 Feb;92(1):51-63. 3. Dixon-Woods M, Bosk CL, Aveling EL, Goeschel CA, Pronovost PJ. Explaining Michigan: Developing an ex post theory of a quality improvement program. Milbank Q 2011 Jun;89(2):167-205. 4. Eliminating CLABSI: A National Patient Safety Imperative. AHRQ Publication No: 11-0037-EF, April 2010. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.ahrq.gov/qual/onthecusprpt/ 5. Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, Sinopoli D, Chu H, Cosgrove S, Sexton B, Hyzy R, Welsh R, Roth G, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2006 Dec 28;355(26):2725-32. 6. Sexton JB, Berenholtz SM, Goeschel CA, Watson SR, Holzmueller CG, Thompson DA, Hyzy RC, Marsteller JA, Schumacher K, Pronovost PJ. Assessing and improving safety climate in a large cohort of intensive care units. Crit Care Med 2011 May;39(5):934-9. 7. Timmel J, Kent PS, Holzmueller CG, Paine L, Schulick RD, Pronovost PJ. Impact of the comprehensive unitbased safety program (CUSP) on safety culture in a surgical inpatient unit. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2010 Jun;36(6):252-60. 8. Wick EC, Hobson DB, Bennett JL, Demski R, Maragakis L, Gearhart SL, Efron J, Berenholtz SM, Makary MA. Implementation of a surgical comprehensive unit-based safety program to reduce surgical site infections. J Am Coll Surg 2012 Aug;215(2):193-200. Appendix A: VAP Prevention Bundle 1. Identify and organize contact information for the members of your CUSP team. Your team may not have members in every category. Consider posting this list prominently, along with a photo of each champion, to build enthusiasm and team cohesion. Name & Title Role Phone & Email Address Senior Executive Partner (Vice President or above) ICU Director / Manager Team Leader Physician Champion Nurse Champion Respiratory Therapist Champion Physicians on team Nurses on team (List all) Respitatory Therapists on team (List all) 1. 2. 3. 4. etc. 1. 2. 3. 4. etc. 1. 2. 3. 4. etc 1. 2. 3. 4. etc. 1. 2. 3. 4. etc. 1. 2. 3. 4. etc 1. 2. 3. 4. 1. 2. 3. 4. Nurse Educator Hospital Patient Safety Officer or Chief Quality Officer Content Specialist (e.g., Infectious Disease Physician; Infection Preventionist) Name & Title Role etc. Staff from Safety, Quality or Risk Management Office Other team members (Fill in role below) 2. 3. Phone & Email Address etc. Appendix B: Team Roles and Responsibilities Purpose of this tool: The purpose of this tool is to help your CUSP team think through the core tasks of this project, and organize yourselves to get the work done. Just like clinical teams, effective improvement teams have clearly defined roles and responsibilities. Explicit delegation helps to share leadership, ownership, and accountability. Please adapt this tool: A teamwork expert designed this tool to help your CUSP for VAP team anticipate and manage project work. Please modify this tool to best fit your team’s needs. As always, we welcome your feedback and encourage you to share your experiences with other CUSP teams in the project. How to use this tool: For each task: Think about the amount of work involved. Do you have enough people? Think about the type of work involved. Do you have the right skill mix? CUSP for VAP tasks You can break each task down into subtasks. Project Tasks Content and coaching calls Who will participate in content and coaching calls? Who will ensure staff availability? Communicate call times to other staff members? Logistics Who will schedule meeting times/locations/conference lines? CUSP (Adaptive work) tasks Educate staff on the science of safety For each group of providers, who will ensure everyone receives training? Engaging executives Who will be the liaison to the executive team member ensuring participation at meetings and presenting CUSP team updates? HSOPS administration Who will be in charge of ensuring high response rates? Staff safety assessment Who will administer, analyze/review, and feedback results to frontline staff? Learning from VAPs and other defects through sensemaking Who will drive the investigation process and dissemination of findings? Implement teamwork tools Who will lead the implementation of Daily Goals Primary contact (initials) Who is accountable for moving this task forward? Supporting roles Who will else will be involved and how? Target due dates and milestones When will tasks or subtasks be completed? CUSP for VAP tasks You can break each task down into subtasks. and other teamwork and communication tools? VAP Prevention (Technical work) Tasks Daily Rounding Form Who will collect and enter the daily rounding data? Data reporting Who will generate reports for VAP process measures and VAE rates? Data feedback Who will provide feedback to frontline providers on VAP process measures and VAE rates? Board of directors, hospital executives, others? Implementation of practice changes Who will lead efforts to align current policies with VAP prevention bundle structural measures? Primary contact (initials) Who is accountable for moving this task forward? Supporting roles Who will else will be involved and how? Target due dates and milestones When will tasks or subtasks be completed? Appendix C: Science of Safety Training Attendance Sheet Clinical Area: _____________________________________ Staff member name Date of training Appendix D: Staff Safety Assessment Purpose of this form: The purpose of this form is to tap into your experiences at the frontlines of patient care to find out what risks jeopardize patient safety in your clinical area. Who should complete this form: All staff members. How to complete this form: Provide as much detail as possible when answering the 4 questions. Drop off your completed safety assessment form in the location designated by the CUSP team. When to complete this form: Any staff member can complete this form at any time. The information requested in this box is optional and not required to complete and submit the Staff Safety Assessment Name (Optional): Job Title: Date: Clinical Area: Assess Risk for Harm 1. Please describe how you think the next patient in your clinical area will be harmed. 2. Please describe what you think can be done to prevent or minimize this harm. Assess Risk for Ventilator Associated Conditions (VAC) 1. Please describe how you think the next patient will develop a ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). 2. Please describe what you think can be done to prevent this VAC/VAP? Appendix E: Executive Safety Rounds Kickoff Template Problem statement: The senior executive is a crucial member of your CUSP for VAP team. He or she has valuable leadership and problem solving skills. Yet the senior executive may not be familiar with your clinical area at the start of the project, and may even be intimidated by it. You can help engage your executive by familiarizing him or her with your clinical area and your team’s safety priorities. Purpose of this tool: You can use this tool at the beginning of your first Executive Safety Rounds to get your senior executive up to speed. It will help you present clinical area information and safety priorities in a concise way. Please adapt this tool: This tool was designed to facilitate communication with their senior executive. Please modify this tool to best fit your team’s needs. As always, we welcome your feedback and encourage you to share your experiences with other CUSP teams in the project. How to use this tool: The CUSP for VAP team lead or a designee should input clinical area information as indicated in this tool. (Examples are included to show you how the tool might look when it’s completed). Make copies of this tool and hand it out to everyone at the start of your first Executive Safety Rounds meeting. You can refer to it as you highlight your clinical area’s characteristics and safety priorities during the meeting. Clinical Area: CUSP for VAP Team Senior Executive Partner: Physician Champion: Nurse Champion: Respiratory Therapist Champion Other Champion: List Other Team Members 1. HSOPS Assessment Composite Scores Share your HSOPS Assessment scores with your senior executive. Examples of information you might share are described below. Survey Close Date: Number of respondents: Response Rate: Tip: You can find the number of respondents and response rate on page 3 of your HSOPS aggregate report. You can copy the composite scores graphs from pages 6 and 7 of your HSOPS aggregate report, below. (The graph on page 6 looks like this): Sensemaking Tip: Consider providing a brief summary of your HSOPS results, highlighting important points or culture score results that you’d like to bring to your senior executive’s attention. 2. Collated Staff Safety Assessment (SSA) Responses In Step 2 of the CUSP for VAP manual your team administered the SSA to your entire staff, and grouped responses by commonly identified defects. You can put that information in this table to help your senior executive get familiar with your clinical area’s safety priorities. Consider summarizing important take-homes in one or two sentences to help your senior executive focus on critical issues, and remember to provide your senior executive with a bit of background on the SSA. Prioritized Safety Issues (Based on Collated Staff Safety Assessment Responses) Response Category E.g., Communication & Teamwork E.g., Infection Control E.g., Equipment Total Number % Staff Safety Assesment Responses You can include some SSA responses here to give your senior executive a more nuanced understanding of your frontline staff’s perspective on safety issues. How the next patient will be harmed? How will the next patient develop a VAP? Category Comments E.g., Communication & Teamwork Ex: Lack of communication between physicians, nurses and anesthesia providers Ex: Everyone not sharing the same information E.g., Infection Control Ex: Oral care with chlorhexidine is not documented well in the patient record Ex: Non-invasive ventilatory equipment is only available through central supply. Ex: Subglottic endotracheal tubes are not readily available on the unit. E.g., Equipment/ Supplies How can we prevent this harm? How can we prevent the next VAP? Category Comments E.g., Communication & Teamwork Ex: Take the completion of Daily Goals and Briefings seriously and when conduct these when everyone is available Ex: Empower all team members to speak up when VAP process measures are being skipped. E.g., Infection Control Ex: Assure that chlorhexidine is used 2 x per day for oral careEx: Assure that everyone practices good hand hygiene before entering the patient’s room Ex. Equipment/ Supplies Ex: Assure that non-invasive ventilatory equipment is stored on the unit Ex: Assure that subglottic endotracheal tubes are well-stocked in the code cart and in the supply areas Sensemaking Tip: Consider building on staff’s suggestions for improvement with specific recommendations for your senior executive 3. Pertinent Clinical Area Information You can include a few bullet points or graphs here with information about your clinical area that your executive may not know. Information may include staff turnover rate, safety event rates, VAE/VAP infection rate, or other pertinent data. Sensemaking Tip: After completing this tool, consider supplementing it with a short summary on the safety issues that you will be exploring in your Executive Safety Rounds. This summary can identify your team’s objectives as you begin a partnership with your senior executive. Appendix F: Safety Issues Worksheet for Executive Partnership Date of Safety Rounds: Unit: Attendees: 1. 5. 2. 6. 3. 7. 4. (Please use back of form for additional attendees.) Identified Issue Potential/Recommended Solution Resources 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. You can copy this form if more than 7 safety issues are identified. Appendix G: Learning from Defects through Collective Sensemaking Tool What is a defect? A defect is any event or situation that you don’t want to repeat. This could include an incident that caused patient harm or put patients at risk for harm, like a patient fall. Problem statement: If a patient is harmed in your care unit area, a typical first response is to help that individual patient, and perhaps even blame his or her providers. This is known as ‘first order’ problem solving because each situation is treated as if it were unique. First order problem solving focuses on the here and now, work-arounds, and ‘quick fixes’. Too few care teams take the opportunity to learn how the defect happened at a systems level, and how to stop it from happening again. This is known as ‘second order’ problem solving because it addresses the underlying causes of the defect. Purpose of this tool: This tool helps you with second order problem solving. Specifically, it helps your team organize ideas about how a defect happened, think about problems and solutions at a systems level, and follow-up with evaluation plans to ensure your solutions worked. Who should use this tool? You need diverse perspectives to assess and troubleshoot your care delivery system. All staff involved in the care system that produced a defect should be present when that defect is evaluated. At a minimum, this should include the nurse, physician, administrator, respiratory therapist and other specialized professionals as appropriate (e.g., for a medication defect, include pharmacy staff; for an equipment defect, include clinical engineering staff). How to use this tool: Complete the form below for at least one defect per quarter, asking the following questions. I. What happened? Provide a clear, thorough, and objective explanation of what happened. II. Why did it happen? Create a list of factors that contributed to the incident and identify whether they harmed or protected the patient. Rate them by how severe and how common they are. III. How will you reduce the likelihood of the defect happening again? Create a plan to reduce the likelihood of this defect repeating. Complete the tables to develop interventions for each important contributing factor, and rate each intervention for its strength. Choose the interventions that you will use based on strength and feasibility. List what you will do, who will lead the intervention, and when you will follow up to evaluate the intervention’s progress. IV. How will you know the risk is reduced? Describe how you will know if you have reduced the risk of a defect repeating. Survey frontline staff involved in the incident to determine whether the plan has been implemented effectively and whether risk has been reduced. I. What happened? Reconstruct the timeline and explain what happened. For this investigation, put yourself in the place of those involved – and in the middle of the event as it was unfolding – to understand what they were thinking and the reasoning behind their actions or decisions. I. Why did it happen? Investigate your care delivery system. Identify harmful and protective contributing factors at each level of your care system in the table. Harmful contributing factors contribute to patient harm; protective factors contribute to patient safety. System Level Patient characteristics Task factors Individual Provider factors Team factors Work Environment Departmental factors Hospital factors Institutional factors Harmful Contributing Factor Protective Contributing Factor II. How will you reduce the likelihood of this defect happening again? Focus your efforts on the most important contributing factors. Rate each harmful contributing factor by 1) How much it contributed to the defect, and 2) Whether it will likely show up again in the future. Harmful Contributing Factors Contributed to Defect 1 (A little) to 5 (A lot) Likely to show up again 1 (Not really) to 5 (Definitely) Conduct a brainstorming session about interventions to address the most important contributing factors. Refer to the Strength of Interventions Chart below for examples of strong and weak interventions. Also consider your protective contributing factors when designing your intervention. Strength of Interventions Weaker Actions Intermediate Actions Stronger Actions Double check Checklists or cognitive aid Architectural or physical plant changes Warnings and labels Increased staffing or reduced workload Tangible involvement and action by leadership in support of patient safety New policy or procedure Redundancy Training and education Enhance communication (e.g., check-back, SBAR) Simplify the process or remove unnecessary steps Additional study or analysis Software enhancement or modifications Standardize equipment and process of care map New device usability testing before purchasing Engineer forcing functions into work processes Eliminate look-alike and soundalike drugs Eliminate or reduce distractions Carefully consider your resources before implementing your intervention. Determine the level of attention your intervention requires by considering the level of support it is likely to receive, and how well the intervention addresses the contributing factor. You can use the following table as a worksheet. Interventions to Address the Harmful Contributing Factor Intervention Addresses the Factor 1 (not well at all) to 5 (really well) Key stakeholders* Level of stakeholder support 1 (strong opposition) to 5 (strong support) Level of attention needed 1 (not much) to 5 (a lot) * Who controls resources? Who needs to have input on your intervention? ** An intervention that addresses the factor really well but has strong opposition requires a lot of attention; an intervention that addresses the factor really well and has strong support requires less attention. You might pay some attention to an intervention that doesn’t address the factor well, if it has strong support; but probably very little attention to an intervention that doesn’t address the factor well and has strong opposition. Choose your interventions and develop an action plan. Improve your chances of success by anticipating and troubleshooting sources of resistance. Finally, ensure accountability by assigning responsibility for efforts, and establish a follow-up date to evaluate intervention success. Chosen Intervention Anticipated sources of resistance Opportunities to reduce resistance Who’s in charge of these efforts? Follow-up Date I. How will you know the risk is reduced? Ask frontline staff involved in the defect whether the interventions improved care. At your follow-up date, complete the “Describe Defect” and “Interventions” sections and have staff rate the interventions. Of course, opinions about the success of interventions are subjective. Your team will need to collect data to objectively measure how successfully an intervention was implemented and how well it reduced the risk of a defect from repeating. Describe Defect: Interventions Intervention Was Implemented Effectively 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree) Intervention Reduced the Likelihood of Defect Repeating 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Definitely) Appendix H: Daily Goals Room Number _____ MD/NP COVERING Pt today: Date ____/____/___ PM shift (7pm) AM shift (7am) **Note Changes from AM** Safety What needs to be done for patient to be discharged from the ICU? Patient’s greatest safety risk? How can we decrease risk? What events or deviations need to be reported? PSN’S? PSN Pain goal ____/10 w/___RASS goal ___w/____ Pain Mgt / Sedation CAM-ICU Daily lightening of sedation (__SAT) if not provider should document why not Patient Care CAM ICU Positive HR Goal_______ at goal Review EKGs ß Block_________ Volume status Net even Net positive Pt determined Net goal for midnight Net neg:____ w/_______ Pulmonary: Ventilator: (HOB elevated, Oral care q4, CHG q12), SAT/SBT) OOB/ pulm toilet/ambulation wean vent (___SBT) Maintain current support mechanics by __am FIO2 <_____ PEEP < ____ plan to extubate Wean as tol (__SBT) Swallow Eval PS/Trach trial ___h x __ Mechs before/after SIRS/Infection/Sepsis Evaluation no current SIRS/Sepsis issues SIRS Criteria Known/suspected infection: Temp > 38° C or < 36 ° C PAN Cx Bld x2 Urine HR > 90 BPM Sputum Other RR > 20 b/min or PaCO2 < 32 torr ABX changes: Initiate / D/C WBC > 12K < 4K or > 10% bands Can catheters/tubes/lines be removed/rewired? ie:foley,CL. (___SAT) Negative Cardiac Wean sedation for extubation in AM Y N If foley cannot be removed provider must document a note why not GI / Nutrition / Bowel regimen NPO TF Type______goal _____ (TPN line, NDT, PEG needed?) TPN INSULIN REQ___ Adj needed y/n DVT: TEDS/SCDs Is this patient receiving DVT/PUD prophylaxis? Hep q8 / q12 / gtt (protocol?) LMWH PUD: PPI H2B N/A Can any meds be discontinued, converted to PO, adjusted? D/C: PO: Renal: Liver: N/A Consents needed/obtained Tests / Procedures/ OR today Scheduled labs N/A (Reassess need q12h) To Do: CMP BMP H8 Coags ABG AM lab needed CXR? Order for restraints? Lactate Core 4 CXR Ordered Wed: Transferrin Iron Prealb 24h urine YN Consultations Does pt meet criteria for mobility protocol? PT/OT/SLP consult Is the primary service up-to-date? Disposition Y N Has the family been updated? Social issues addressed (LT care, palliative care) ICU status ___ IMC status: vitals q______ Y N Family meeting today? Y N N/A Fellow/Attg Initials: ______ Nursing Initials: ______ line change Appendix I: Shadowing Another Professional Problem Statement: Health care delivery is a multidisciplinary practice that requires coordination of care among different professions and provider types. However, health care providers often do not understand other disciplines’ daily responsibilities, teamwork, and communication issues. This disconnect may inhibit the effective coordination of patient care. How does shadowing another profession benefit the participant? Shadowing another provider allows the “shadower” to gain a broader perspective of the role other professions play in patient care. The shadower will observe communication practices, and reflect on the impact they have on collaboration and teamwork. Shadowers can identify communication and teamwork defects that may lead to poor patient outcomes. Purpose of tool: This tool offers a structured approach to identify, and then improve, communication, collaboration, and teamwork defects that impact patient care delivery. Who should use this tool? Staff unfamiliar with responsibilities and practice domains of another profession. How to use this tool: Review this tool before your shadowing experience to help you recognize important teamwork and communication issues. Use this document to identify problems observed in patient care areas within the practice setting of the individual you are shadowing. Spend as much time as possible within another practice domain. At the end of your shadowing experience: I. Review your list of observed communication and teamwork problems. Be objective and use a systems approach to look at patient care delivery. II. Collaborate with the provider you shadowed to reduce communication errors and teamwork problems that impact patient care. III. Prepare a draft of the problems identified and your proposed solutions. Meet with your CUSP for VAP team to discuss your findings. Date: Shadowing Another Provider I. What happened during the shadowing exercise? (Outline your observations. For this experience, put yourself in the place of the other provider and try to view the world as he or she does.) II. Put the pieces together. Below is a framework to help you identify communication and teamwork issues that affect patient care and the teamwork climate in the unit. Please read and answer the following questions. Yes 1. Were any health care providers difficult to approach? How did that affect the effectiveness of the health care provider you shadowed (e.g., order ignored)? (Write some notes, below) What was the final outcome for the patient (e.g., delay in care)? (Write some notes, below) Did this unapproachable provider detract from the teamwork climate in the unit? Did the provider you shadowed seem comfortable working with this difficult provider? 2. Was one provider approached more often for patient issues? If yes, was it because another health care provider was difficult to work with? If one provider was approached more often, what patient care issues evolved (e.g., delay in care delivery, provider overwhelmed)? (Write some notes, below) 3. Did you observe any error in transcription of orders by the provider you shadowed? 4. Did you observe any error in the interpretation or delivery of an order? 5. Were patient problems identified quickly? No N/A Yes Were they handled as you would have dealt with them? Why or why not? (Write some notes, below) Were there obstacles that prevented effective handling of the situation (e.g., lack of staff, equipment)? Did the providers involved seek help from a supervisor? 6. If you shadowed a nurse: Was the nurse’s page or phone call returned quickly when there was an important issue? If yes, what was the outcome for the patient? (Write some notes, below) Were patient medications available to the nurse when they were due? If no, what was the average wait time? (Write some notes, below) How did the nurse react if the medication was late (e.g., anxious, angry, upset)? (Write some notes, below) If the medications were delayed, could this affect the patient’s outcome (e.g., delay in discharge)? 7. If you shadowed a physician: Did the physician face obstacles in returning calls or pages? If yes, what were the obstacles? (Write some notes, below) Did other factors affect the physician’s ability to see patients? If yes, what were they? (Write some notes, below) Did the physician receive clear information or instructions? 8. If you shadowed a pharmacist: Did the pharmacist face obstacles in dispensing on time? If yes, what were the obstacles? (Write some notes, below) No N/A Yes No N/A 9. How would you assess: Hand-offs: During the hand-off, were verbal or written communications clear, accurate, clinically relevant, and goal directed? (That is, did the outgoing care team debrief the oncoming care team regarding the patient’s condition?) If no, explain why. (Write some notes, below) Communication during a crisis: During a crisis, were verbal or written communications clear, accurate, clinically relevant, and goal directed? (That is, did the team leader quickly explain and direct the team regarding the plan of action?) If no, explain why. (Write some notes, below) Provider skill: Did the provider you shadowed seem skilled at all procedures he or she performed? If no, did he or she seek out a supervisor for assistance? (Write some notes, below) Staffing: Did staffing affect care delivery? If yes, explain why. (Write some notes, below) III. Now that you have shadowed a person in another profession, what will you do differently in your clinical practice to communicate more effectively? IV. What suggestions do you have for improving teamwork and communication? Specific Recommendations Actions Taken Appendix J: Briefing Tool Problem Statement: Communication between ICU physicians and nursing staff does not always results in efficiently and effectively prioritization of patient care delivery and ICU admissions and discharges. What is a Briefing? A briefing is a dialogue between 2 or more people using concise and relevant information to promote effective communication prior to rounds in the inpatient unit. Purpose of Tool: The purpose of this tool is to provide a structured approach to assist physicians and charge nurses in identifying the problems that occurred during the night and potential problems during the clinical day. Who Should Use this Tool? Physicians who conduct patient rounds. Charge nurses and nurse managers who make patient assignments and are responsible for the entire patient population and staff within the inpatient unit. How to Use this Tool: Complete this tool daily prior to starting patient care rounds by meeting with the charge nurse. Briefing Process I. What happened overnight that I need to know about? After an update on the patients proceed to question II unless there was an adverse event involving one of the patients. IF an adverse event occurred you may implement How to investigate a defect? II. Where should I begin rounds? Below is a framework to help review your patient population, planned admissions and discharges. Based on your assessment after reviewing the following questions, you should be able to identify if you start rounds because of patient acuity or if you start rounds with the first patient to transfer out to more efficiently prepare for the units first admission. 1. IS THERE A PATIENT THAT REQUIRES MY IMMEDIATE ATTENTION SECONDARY TO ACUITY? 2. Which patients do you believe will be transferring out of the unit today? 3. Who has discharge orders written? 4. How many admissions are planned today? 5. What time is the first admission? 6. How many open beds do we have? 7. Are there any patient having problems on an inpatient unit? YES/NO NAME/ROOM NUMBER III. Do you anticipate any potential defects in the day? Problem identified Specific things to consider? Patient scheduling Equipment availability/ problems Outside Patient testing/Road trips Physician or nurse staffing Provider skill mix Person assigned to follow up Action taken Appendix K: Observing Rounds Tool Problem Statement: Interdisciplinary rounds are in the best interest of patients. Communication is a root cause of many patient adverse and sentinel events. Communication among disciplines could be improved if viewed through the objective eye of a non-participant. What is Observational Rounds? Observational rounds is a teamwork and communication tool to objectively assess and improve (1) teamwork dynamics across and between disciplines, (2) identify areas where communication could be more concise and relevant in setting daily patient goals, and (3) provide a method to continually improve communication skills. Purpose of Tool: The purpose of this tool is to provide a structured approach for improving teamwork and communication behaviors across and between disciplines that negatively affect staff morale and patient care delivery. Who Should Use this Tool? Physicians who conduct patient rounds. Administrators, house officers, nurses, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, medical and nursing students should use this tool to: (1) better understand the dynamics of multidisciplinary rounds, (2) identify defects in communication, (3) foster collaboration among disciplines or practice domains, and (4) target areas where communication can be improved in the rounding process and in setting patient daily goals. How to Use this Tool: Complete this tool while observing patient care rounds. Discuss your findings with the multidisciplinary team at the end of rounds. You may use this for one patient or the entire unit. There are leading questions and prompts to encourage teamwork and communication assessment from a broad perspective on the attached page. Observation Process: Questions to consider III. Identify communication that was explicit (clearly stated and measurable), versus implicit (suggested, but not clearly expressed). a. Who was explicit in their communication? b. Were care directives ever implied, but not clearly expressed? If yes, by whom? And, within which practice domain? Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Dietary, Respiratory IV. Did anyone ask for clarification? If yes, what team members spoke up? Were rounds conducted in an open forum (all team members could participate and make suggestions) or closed (led by the attending, dealt with the primary resident caring for the specific patient)? If rounds were in an open forum, were team members encouraged to offer opinions/ suggestions? If the rounds were in a closed forum, would input from other team members benefit the patient or the plan of care? Was there something missing in the patient care goals? If so, fill-in below: Patient Room Patient system, goal not addressed V. Were conflicts identified in a patient’s plan of care? How were the conflicts resolved? Was hierarchy, attending physician over resident an issue? Was change in plan of care supported by evidence-based medicine (literature)? Did the interaction style and/or communication change between providers? VI. Were you able to identify assertive behavior or communication? Was it appropriate for the situation? VII. Were team members able to maintain situational awareness (Aware of activities going on in the unit) Where changes in the average day clearly identified? How were these changes resolved? Effective vs. Ineffective? VI. At the end of rounds, what do you wish you would have said that you did not say? Below is a framework to help review your findings with members of the team. Based on your observations and after reviewing the preceding questions, list any teamwork and communication problems you identified during the course of patient rounds. Points for Discussion with team Problem Team members affected Patient care not addressed Suggestions/Actions Appendix L: Barrier Identification and Mitigation Tool Tool Overview Problem Statement: Guidelines summarizing evidence exist to help ensure that patients receive recommended interventions. In addition, consistent guideline adherence may significantly improve patient safety. However, adherence to these evidence-based guidelines remains highly variable both within and between units, hospitals, and states. Tools to identify factors which hinder guideline adherence (i.e. barriers) and approaches to mitigating these barriers within individual clinical units are also lacking. What Types of Barriers Exist? Barriers to achieving consistent adherence to evidence-based guidelines are commonly related to provider, guideline, and system characteristics. Purpose of Tool: Since particular barriers and the corresponding solutions may differ between individual clinical units, the Barrier Identification and Mitigation (BIM) Tool was designed to help frontline staffs systematically identify and prioritize barriers to guideline or intervention adherence within their own care setting. This tool also provides a framework for developing an action plan targeted at eliminating or mitigating the effects of the identified barriers. By providing both a practical and interdisciplinary approach to recognizing and addressing barriers, the BIM tool may serve as an aid to quality and safety improvement efforts. Who Should Use this Tool? Both frontline clinicians (e.g., physicians and nurses) and nonclinicians (e.g., unit administrator, unit support staff, hospital quality officer) within the care setting being targeted by a particular quality improvement initiative, such as CUSP for VAP, may utilize this tool. Frequently, BIM Team members are a subcommittee of the unit’s quality improvement team (e.g., CUSP Team) as identified in the unit’s Background CUSP Team Information Form. In addition, all BIM Team members should be trained in the CUSP Toolkit and have viewed the Science of Improving Patient Safety video. How to Use this Tool: The BIM tool is best applied within the context of a comprehensive quality and safety improvement effort, such as CUSP for VAP. This tool should be used periodically (every three to six months or so) to identify barriers if adherence to a guideline or therapy is poor. This document summarizes the 5 step process and provides more detailed explanations and sample forms for each step. Summary of Barrier Identification and Elimination/Mitigation Process Step 1: Assemble the interdisciplinary team: Compose a diverse team with an array of associates from the targeted unit’s Quality Improvement (QI) Team. BIM Team Information Form (Form 1): Gathers contact information for the BIM team members and is completed by the designated BIM Team leader. Step 2: Identify Barriers: Several different team members should work independently to identify and record barriers to guideline adherence in the targeted clinical area. They should do this by way of observing the process being impacted by the guideline, asking about this process, and actually walking through a simulation of the process or, if appropriate, real clinical practice. Barrier Identification Form (Form 2): Provides a framework for identifying and recording barriers, contributing factors to barriers, and potential actions to ameliorate those barriers. Completed by individual team members engaged in observing, asking about, or walking the process impacted by guideline Step 3: Compile and summarize the barrier data: Upon completion of all data collection, an assigned team member should compile all of the barrier data recorded by the several investigators. This team member should then summarize this information and record any suggestions provided by observers to improve adherence. Barrier Summary and Prioritization Table (Form 3): Template for summarizing barriers, specifying each barrier’s relation to the guideline, identifying method of data collection, and rating each barrier with a likelihood, severity, and priority score. Completed during team meeting. Step 4: Review and prioritize the barriers: The Barrier Identification and Mitigation (BIM) Team should then review and discuss the barrier summary. Next, the BIM Team should rate each barrier on the likelihood of the barrier occurring within the unit and the severity of the barrier’s impact on guideline adherence if it should occur. By multiplying the likelihood and severity scores together to arrive at a priority score, the QI team will have an understanding of how imperative it is to address each barrier. Step 5: Develop an action plan for each targeted barrier: The BIM team should review all suggested actions to eliminate/mitigate the selected high priority barriers. Then, the BIM team should collectively select individual actions for the next improvement cycle based on the potential impact of each action on the eliminating or ameliorating the barrier and the feasibility of effectively implementing the action based on available resources. Based on these two factors, an action priority score is calculated such that the higher the score, the higher the priority. Action Plan Development Table (Form 4): Framework for compiling high priority barriers, potential actions to eliminate/mitigate barriers, and evaluation measures to assess those actions. Framework also provides mechanism to score potential actions as far as their potential impact, feasibility and priority. This may be completed during a team meeting. STEP 1: ASSEMBLE INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAM First, compose a diverse team to examine a specific quality problem. This BIM Team should be a subcommittee of the unit’s Quality Improvement (QI) Team (e.g., CUSP Team). Throughout this BIM process, investigators will be viewing the targeted care setting as the “patient” in order to identify any barriers to providing evidence based care that may be occurring. Thus, make sure the team is interdisciplinary and includes members of differing levels of experience and training to more validly characterize local barriers, develop an action plan to overcome these difficulties, and achieve consistent guideline adherence. Perhaps provide an open invitation to join the team at a quality improvement staff meeting or through an email to the QI Team for the targeted care setting. Within the QI Team, encourage clinical staff that work in the unit (e.g., physicians, nurses), support staff (e.g., unit administrators, technicians), and content experts (e.g. hospital quality officers) to join the BIM team. Then, by group consensus, assign team members to necessary roles and responsibilities including a chair of the BIM Team. Brief the BIM team on the types of barriers to guideline adherence (e.g. provider, guideline or system level), the importance of overcoming these barriers, the evidence surrounding the utility of the tool, and on the BIM tool itself. Additionally, all BIM Team members should be trained on the science of patient safety (e.g., having viewed the Science of Improving Patient Safety video and be familiar with the overall process for improving quality (e.g., reviewed the CUSP Toolkit). List the team member names and responsibilities on the Background BIM Team Information Form (below). BIM TEAM INFORMATION FORM Step 1: Assemble the Interdisciplinary Team and indicate the persons designated as BIM Team Members (fill in as applicable). Your team may not have people in all of these categories. ROLE Medical director of unit Additional Physician Additional Physician Nurse Practitioner/ Nurse Specialist Nurse manager for unit Additional nurse Non-clinical administrator for unit Hospital administrator Quality improvement specialist Human factors engineer Technician for unit Other unit support staff member Other content experts NAME & TITLE RESPONSIBILITIES WITHIN BIM TEAM STEP 2: Identify Barriers Several team members should work independently to identify barriers to consistent guideline adherence in the targeted clinical area. Utilizing different modes of data collection facilitates obtaining an accurate and complete picture of the factors influencing guideline adherence. Observe: Observe a few clinicians engaged in the tasks related to the guideline. Remember that your role is to observe, so cause as little distraction as possible. Focus more on observing than documentation during the observation period. Jotting a few notes is okay, but wait to complete the Barrier Identification Form until immediately following the observation period. Along with recording the barriers to achieving consistent adherence to the guideline that were witnessed, indicate any steps in the process that were skipped and workarounds (i.e., improvised process steps or factors that facilitated guideline adherence) Discuss: Ask various staff members about the factors influencing guideline adherence. This may include informal discussions, interviews, focus groups, and brief surveys. Assure the confidentiality of staff responses Also ask staff about the problems they face and any ideas they have regarding potential solutions for improving guideline adherence. 1) Are staff aware that the guideline exists? 2) Do staff believe that the guideline is appropriate for their patients? 3) Do staff have any suggestions to improve guideline adherence? Walk the Process: Consciously follow the guideline during a simulation, or if appropriate, during real clinical practice. Investigators should continue collecting data until no new barriers are identified upon new data collection, and a comprehensive understanding of good practices and barriers to guideline adherence is achieved. This process should take approximately 3 to 6 hours. The investigators should record all potential reasons that clinicians were experiencing difficulties with adhering to the guideline (i.e. guideline barriers), and factors encouraging guideline adherence (i.e. guideline facilitators) in the Barrier Identification Form. Additionally, within the Barrier Identification Form, investigators should indicate the method of data collection (e.g. observation, survey, focus group, informal discussion, interview, or walking the process), the associate who collected the data, and the clinical unit from which the data was collected. BARRIER I DENTIFICATION FORM Step 2: Identify Barriers to guideline adherence by observing, asking about and walking the process. GUIDELINE: DATA COLLECTION MODE : INVESTIGATOR: FACTORS PROVIDER Knowledge of the guideline What are the elements of the guideline? Attitude regarding the guideline What do you think about the guideline? Current practice habits What do you currently do (or not do)? Perceived guideline adherence How often do you do everything right? GUIDELINE Evidence supporting the guideline How “good” is the supporting evidence? Applicability to unit patients Does the guideline apply to the unit’s patients? Ease of complying with guideline How does adherence affect the workload? SYSTEM Task Who is responsible for following the guideline? Tools & technologies What supplies & equipment are available/used? Decision support How often are aids available and used? Physical environment How does the unit layout affect adherence? Organizational structure How does the organizational structure (e.g. staffing) affect adherence? Administrative support How does the administration affect adherence? Performance monitoring/feedback How does the unit know it is following the guideline? Unit culture How does the unit culture affect adherence? OTHER UNIT: BARRIER (S) POTENTIAL ACTIONS Step 3: Compile and summarize the barrier data Once data collection is complete, a team member should compile all of the data from the various investigators in the above Barrier Identification Form. The information should then be summarized in columns 1, 2, and 3 of the Barrier Summary and Prioritization Table. In column 1, briefly summarize each barrier; in column 2, provide a brief description of the part of the guideline to which the particular barrier pertains; then in column 3, provide the source of data collection (i.e. observation, survey, interview, informal discussion, focus group, walking the process). Finally, this team member records any suggestions provided by observers to improve guideline adherence in the Framework for the Development of an Action Plan. Step 4: Review and prioritize the barriers As a team, review and discuss the barrier summary. Then, in columns 4, 5, & 6 of the Barrier Summary and Prioritization Table, rate each barrier on the likelihood of the barrier occurring in the unit (likelihood score) and the probability that it, if encountered, would lead to guideline nonadherence (severity score). Each barrier is scored from 1, indicating a low likelihood or severity, to 4, indicating a high likelihood or severity. The priority score for each barrier is then calculated by multiplying the likelihood and severity scores. The higher the priority score for a barrier, the more critical it is to eliminate or mitigate the effects of that barrier. As a team, develop your own criteria for determining which barriers to target during this Quality Improvement cycle. For instance, you could set a priority score threshold to decide which barriers to target (e.g. barriers with a priority score ≥ 9) or target the top 3 barriers. BARRIER SUMMARY AND PRIORITIZATION T ABLE Step 3 & 4: Compile, summarize, review as a team, and prioritize the barrier data collected from the investigators. BARRIER RELATION TO GUIDELINE SOURCE LIKELIHOO D SCORE * SEVERITY SCORE** BARRIER PRIORITY SCORE*** TARGET FOR THIS QI CYCLE? * Likelihood score: How likely is it that a clinician will experience this barrier? 1. Low 2. Moderate 3. High 4. Very High ** Severity score: How likely is it that experiencing this particular barrier will lead to non-adherence with the guideline? 1. Low 2. Moderate 3. High 4. Very High *** Barrier priority score = (likelihood score) x (severity score) Step 5: Develop an action plan for each targeted barrier As a team, list and review the potential actions to eliminate/mitigate the selected high priority barriers in the Framework for the Development of an Action Plan - as suggested by the observers in Step 2. Next, identify any additional potential actions using brainstorming techniques and record these in the Framework for the Development of an Action Plan as well. Then, collectively select individual actions for the next improvement cycle based on the potential impact of each action on the barrier as far as improving guideline adherence (if the action is successfully implemented) and the feasibility of effectively implementing the action based on the resources currently available. Thus, rate each suggested action with a potential impact score and a feasibility score. As in Step 4, each action is scored from 1, indicating a low impact or feasibility, to 4, indicating a high impact or feasibility. The action priority score for each potential action is then calculated by multiplying the potential impact score and the feasibility score together. Teams should consider setting a threshold action priority score for which actions to pursue during the upcoming quality improvement (QI) cycle. It is critical to closely examine the feasibility of implementing an action. For example, placing a sink within each patient’s room may increase the frequency of clinicians washing their hands, but may not be as cost effective as placing a dispenser for hand sanitizer within each patient’s room. For each action, the group should assign an appropriate leader, performance measures, and follow-up dates to evaluate progress. This information should be recorded in the Framework for the Development of an Action Plan as well. FRAMEWORK FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN ACTION PLAN Step 5: Develop an action plan for each targeted barrier. PRIORIT POTEN IZED BARRIE RS TIAL ACTION S POTEN SOU RCE TIAL IMPACT SCORE * ACTIO FEASIBI LITY SCORE * * N PRIOR ITY SCOR E*** SELE CT FOR THIS QI CYCL E? ACTI PERFORM ON LEAD ER ANCE MEASURE (METHOD) FOLL OW UP DATE *Potential impact score: What is the potential impact of the intervention on improving guideline adherence? 1. Low 2. Moderate 3. High 4. Very high **Feasibility score: How feasible is it to take the suggested action? 1. Low 2. Moderate 3. High 4. Very high ***Action priority core = (Potential impact score) x (feasibility score)