Understanding Economics

6th edition

by Mark Lovewell

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Chapter 5

Perfect Competition

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.

Learning Objectives

After this chapter you will be able to:

distinguish the four market structures, and the main

differences among them

2. understand the profit-maximizing rule and how

perfect competitors use it in the short run

3. identify how perfect competitive markets adjust in the

long run, and the benefits they provide to consumers

1.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Market Structures

There are four main market structures:

perfect competition

monopolistic competition

oligopoly

monopoly

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Perfect Competition

Perfectly competitive markets have three main

features:

many buyers and sellers

a standard product

easy entry and exit

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Monopolistic Competition

Monopolistically competitive markets have three main

features:

many buyers and sellers

slightly different products

easy entry and exit

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Oligopoly and Monopoly

In an oligopoly a few businesses (protected by entry

barriers) provide standard or similar products.

In a monopoly a single business (protected by entry

barriers) provides a product with no close substitutes.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Entry Barriers

There are six main entry barriers in oligopolies and

monopolies:

increasing returns to scale

market experience

restricted ownership of resources

legal obstacles (such as patents)

market abuses (such as predatory pricing)

advertising (which is most common in oligopolies)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Market Power

Market power:

is a business’s ability to affect the price it charges

varies with market structure, such that monopolists

have the most and perfect competitors have the least

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

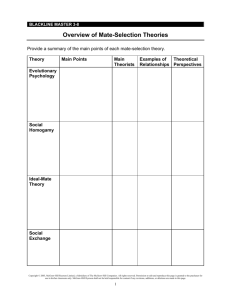

Attributes of Market Structures

Figure 5.1, Page 119

Perfect

Competition

Monopolistic

Competition

Oligopoly

Monopoly

very many

many

few

one

Type of

Product

standard

differentiated

standard or

differentiated

not

applicable

Entry and Exit of

New Business

very easy

fairly easy

difficult

very

difficult

none

some

some

great

farming

restaurants

automobile

manufacturing

public

utilities

Numbers of

Businesses

Market Power

Example

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Perfect Competitor’s Demand (a)

A perfect competitor has a demand curve different

from the market demand curve.

The business’s demand curve is horizontal at the

prevailing market price.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Perfect Competitor’s Demand (b)

Figure 5.2, page 121

Pure ‘n’ Simple T-Shirts’

Demand Curve

Market Demand and Supply

Curves for T-Shirts

6

Dm

0

Price ($ per T-Shirt)

Price ($ per T-Shirt)

Sm

27 000

Quantity of T-Shirts per Day

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

6

0

Quantity of T-Shirts per Day

Db

Average and Marginal Revenue

Total revenue is used to find two other revenue

concepts:

average revenue (total revenue divided by output)

marginal revenue (change in total revenue divided by

change in output)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Revenue Conditions for a Perfect

Competitor

Average revenue equals price, so that a perfect

competitor’s average revenue curve is its horizontal

demand curve.

A perfect competitor’s average revenue (price) is

constant so that marginal revenue and average revenue

are always equal.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Revenues for a Perfect Competitor

Price

(P)

($ per T-shirt)

$-6

6

6

6

6

Revenue Schedules for Pure ‘n’ Simple T-Shirts

Total Revenue Marginal Revenue

(TR)

(MR)

(P x q)

(ΔTR/Δq)

Quantity

(q)

(T-Shirts per day)

$ 0

80

200

250

270

280

$

0

480

1200

1500

1620

1680

Average Revenue

(AR)

(TR x q)

480/80 = $6

720/120 = 6

300/50 = 6

120/20 = 6

60/10 = 6

Revenue Curves for Pure ‘n’ Simple T-Shirts

$ per T-Shirt

Figure 5.3, page 122

6

Db = AR = MR

0

Quantity of T-Shirts per Day

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

480/80 = $6

1200/200 = 6

1500/250 = 6

1620/270 = 6

1680/280 = 6

The Profit-Maximizing Output

Rule

The profit-maximizing output rule states that profit is

maximized when marginal revenue equals marginal

cost. This means:

output should be increased if marginal revenue exceeds

marginal cost

output should be decreased if marginal cost exceeds

marginal revenue

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Profit Maximization for a Perfect Competitor

Figure 5.4, page 124

Profit Maximization Table for Pure ‘n’ Simple T-Shirts

Total

Product

(q)

Price

(P)

(=AR)

0

80

200

250

270

280

$6

6

6

6

6

6

Marginal

Revenue

(MR)

Marginal

Average

Cost

Variable Cost

(MC)

(AVC)

(ΔTC/Δq)

(VC/q)

$6

6

6

6

6

$1.75

1.33

2.50

5.50

10.50

$1.75

1.50

1.70

1.98

2.29

Average

Cost

(AC)

(TC/q)

Total

Revenue

(TR)

$

$12.06

5.63

5.00

5.04

5.24

0

480

1200

1500

1620

1680

Total

Cost

(TC)

Total

Profit

(TR - TC)

$ 825

965

1125

1250

1360

1465

$-825

-485

75

250

260

215

Profit Maximization Graph for Pure ‘n’ Simple T-Shirts

MC

6.00

a

Db = MR = AR

Profit = $260

5.04

AC

$ per T-Shirt

b

AVC

0

270

Quantity of T-Shirts per Day

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

The Breakeven and Shutdown

Points

The breakeven point is where a business breaks even

while maximizing profit.

For a perfect competitor this occurs where price equals

minimum average cost.

The shutdown point is the lowest price at which a

business will choose to operate in the short run.

It occurs where price equals minimum average variable

cost.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

A Perfect Competitor’s Supply

Curve

A perfect competitor’s supply curve is its marginal cost

curve above the shutdown point.

The market supply curve can be found by horizontally

adding the supply curves for all the businesses in the

industry.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Supply Curve for a Perfect

Competitor

Figure 5.5, page 126

Supply Curve for Pure ‘n’ Simple T-Shirts

Supply Schedule for

Pure ‘n’ Simple T-Shirts

($ per T-Shirt

$6.00

5.00

1.50

1.40

Quantity

Supplied

(q)

(T-Shirts per day)

270

250

200

0

a

6.00

$ per T-Shirt

Price

(P)

MC(=Sb)

5.00

b

MR1

AC

MR2

AVC

c

1.50

1.40

d

0

200

Quantity of T-Shirts per Day

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

250 270

Supply Curves for a Perfectly Competitive Business

and Market

Figure 5.6, page 127

Business and Market Supply Schedules for T-Shirts

Price

(P)

Quantity Supplied

(q)

(Q)

(Sb)

(Sm)

(T-Shirts per day)

($ per T-Shirt)

$6.00

5.00

1.50

270

250

200

Supply Curve for T-Shirt Market

Sb

6.00

5.00

1.50

0

200

250 270

Price ($ per T-Shirt)

Price ($ per T-Shirt)

Supply Curve for

Pure ‘n’ Simply T-Shirts

27 000

25 000

20 000

Sm

6.00

5.00

1.50

0

Quantity of T-Shirts per Day

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

20 000 25 000 27 000

Quantity of T-Shirts per Day

Perfect Competition in the Long

Run

Entry and exit by businesses in the long run drives a

perfectly competitive market to the breakeven point.

Businesses enter markets where economic profits are

made so that supply shifts right and price falls.

Businesses leave markets where economic losses are

made so that supply shifts left and price rises.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Long-Run Equilibrium for a

Perfectly Competitive Business

Figure 5.7, page 129

Pure ‘n’ Simply T-Shirts

T-Shirt Market

MC

S0

6

b

a

5

MR

$ per T-Shirt

$ per T-Shirt

AC

S1

d

6

5

e

c

D0

0

250 270

Quantity of T-Shirts per Day

0

25 000 27 000 30 000

Quantity of T-Shirts per Day

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

D1

The Benefits of Perfect

Competition

Perfectly competitive markets in long-run equilibrium

meet two conditions that benefit consumers:

minimum-cost pricing (price = minimum average cost)

marginal-cost pricing (price = marginal cost)

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

How Resource Markets Operate

Marginal Productivity Theory

The demand for resources is based on the demand for

the products that these resources are used to produce.

According to marginal productivity theory, businesses

use resources based on how much extra profit each of

these resources provides.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

How Resource Markets Operate

The Determinants of Demand

Three factors are important in determining the

demand for a resource:

a resource’s marginal cost

a resource’s marginal product

the marginal revenue of new units of output

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

How Resource Markets Operate

A Product and Resource Price-Taker

If a business is a price-taker in its product and resource

markets:

the resource’s marginal cost is constant

the resource’s marginal product is variable

the marginal revenue of new units of output is constant

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

How Resource Markets Operate

The Profit-Maximizing Employment Rule

The profit-maximizing employment rule states that

profits are maximized when marginal revenue product

equals marginal resource cost.

Marginal revenue product is the change in total revenue

when employing a new unit of a resource.

Marginal resource cost is the change in total cost when

employing a new unit of a resource.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

How Resource Markets Operate

Labour Demand and Supply for a Product and Resource Price-Taker

Figure A

Labour Demand and Supply Schedules for a Strawberry Farm

Labour Total Product

(L)

(P)

(no. of

(q)

workers) (kilograms)

0

10

18

24

28

30

$2

2

2

2

2

2

10

8

6

4

2

Marginal

Marginal

Revenue

Resource Cost

Product

(MRC = W)

(MRP = ΔTR) ($ per hour)

$0

20

36

48

56

60

$20 (a)

16 (b)

12 (c)

8 (e)

4 (f)

Labour Demand and Supply Curves for a Strawberry Farm

Wage ($ per hour)

0

1

2

3

4

5

Marginal Product

Output Price

Total

(MP)

(P)

Revenue

(Δq/ΔL)

(TR)

(kilograms)

($ per kilogram) (P x q)

20

16

a

b

12

c

MRC = Sb

d

8

e

4

0

f

1

2

3

4

No. of Workers

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

MRP = Db

5

$10

10

10

> (d)

10

10

How Resource Markets Operate

Market Demand and Supply

In a competitive labour market:

the market demand curve is found by horizontally

summing the labour demand curves for all businesses in

the industry

the market supply curve shows the total number of

workers offering their services in this industry at each

wage

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

How Resource Markets Operate

Demand and Supply in a Competitive Labour Market

Figure B

Labour Demand and Supply Curves

for Strawberry Farm Workers

Labour Demand and Supply Schedules

for Strawberry Farm Workers

$18

14

10

6

2

Labour Demanded

(DM)

(no. of

workers)

(farm)

(no. of

workers)

(market)

Labour

Supplied

(SM)

(no. of

workers)

(market)

1

2

3

4

5

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

5000

4000

3000

2000

1000

SM

18

Wage ($ per hour)

Wage

(W)

($ per

hour)

14

10

e

6

2

0

DM

1000 2000 3000 4000 5000

No. of Workers

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

How Resource Markets Operate

Demand for Other Resources

Marginal productivity theory is not always applicable

to other resources.

The theory can be employed for labour and for natural

resources, because these resources are measured in

standardized units.

It is harder to calculate marginal revenue product for

capital goods, because one investment project differs

from another.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Can Capitalism Survive?

Joseph Schumpeter:

believed that entrepreneurs are the driving force of

economic progress in capitalism

predicted that capitalism was doomed because of the

growing dominance of government bureaucracy

antagonistic to capitalism

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Resource Demand (OLC)

A Product Price-Maker/ Resource Price-Taker (a)

If a business is a price-maker in its product market and

a price-taker in its resource market, then:

the resource’s marginal cost is constant

the resource’s marginal product varies

the marginal revenue of the new units of output falls as

quantity rises

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Resource Demand (OLC)

A Product Price-Maker/ Resource Price-Taker (b)

Just as in the case of a business that is a price-taker in

its product market, the profit-maximizing rule also

applies in this case of a product price-maker.

In other words, the business should use a resource up

to the point where its marginal revenue product and

its marginal revenue cost intersect.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Resource Demand (OLC)

Labour Demand and Supply for a Product PriceMaker/Resource Price Taker Figure A

Labour Demand and Supply Curves

for Nirvana Cushions

Labour Demand and Supply Schedules

for Nirvana Cushions

0

1

2

3

4

Total

Marginal Output

Total

Product

Product

Price Revenue

(P)

(MP)

(P)

(TR)

(q)

(Δq/ΔL)

(P x q)

(no. of

(no. of

cushions) cushions)

0

4

7

9

10

4

3

2

1

$10

8

6

5

4

$0

32

42

45

40

Marginal

Revenue

Product

(MRP =

ΔTR/ ΔL)

$32 (g)

10 (h)

3 (j)

-5 (k)

Marginal

Resource

Cost

(MRC = W)

($ per hour)

$7

7

> (i)

7

7

Wage ($ per hour)

32

Labour

(L)

(no. of

workers)

g

h

10

7

3

0

-5

i

MRC = Sb

j

1

2

3

k4

5

MRP = Db

No. of Workers

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Resource Demand (OLC)

Market Demand and Supply

If the resource market this business is

operating in is competitive, the degree of

competition in the product does not affect

how market demand in the resource market

is determined.

As before (as shown in the text appendix),

the resource demand curves of all businesses

are combined to find the market demand

curve.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Resource Demand (OLC)

Changes in Resource Demand (a)

There are three main resource demand

factors: product prices, resource prices, and

technological change.

Resource demand is affected by changes in

product prices. For example, a rise in a

product price causes the MRP for relevant

resources to rise, shifting demand for these

resources to the right.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Resource Demand (OLC)

Changes in Resource Demand (b)

To identify the effect of other resources

prices, we must distinguish two types of

resource combinations.

Complementary resources are used together

(e.g. steam shovels and steam-shovel

operators). The price for one of these

resources and the demand for the other have

an inverse relationship. For example, a drop in

the price of steam shovels increases the

demand for steam shovel operators.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Resource Demand (OLC)

Changes in Resource Demand (c)

Substitute resource are used in place of one

another (e.g. steam shovels and manual

labour). The price for one of these resources

and the demand for the other have a direct

relationship. For example, a drop in the price

of steam shovels decreases the demand for

manual labour.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Resource Demand (OLC)

Changes in Resource Demand (d)

Technological innovation has two possible

effects. If a new or more productive type of

machine is introduced, for example,

complementary resources will increase in

demand, while demand for substitute

resources will decrease.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

A Measure of Justice (OLC) (a)

The ancient philosopher Aristotle:

stated that trade should be based on an ‘equality of

proportion’ between the two items being exchanged

was the first to point out the potential injustices caused

by monopoly power

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

A Measure of Justice (OLC) (b)

Aristotle distinguished two types of value:

Use value relates to a good’s intrinsic characteristics.

Exchange value relates to how much a good can fetch in

return for other goods.

Aristotle saw these values as distinct, based on the socalled paradox of value, whereby some rare goods such

as gold are worth more than useful goods such as iron.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

A Measure of Justice (OLC) (c)

According to Aristotle and his followers (both

historical and present-day), a overemphasis on the

exchange values of products diminishes our ability to

recognize real worth.

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson

Limited. All rights reserved.

Chapter 5

The End

Copyright © 2012 by McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited. All rights reserved.