Homelessness The homeless are one of the most marginalized

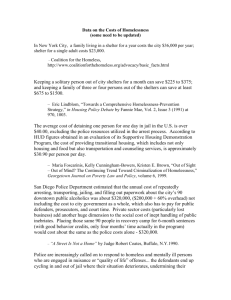

advertisement

1 Homelessness The homeless are one of the most marginalized groups in society. They are misunderstood and there is a stigma against them. Those under our overpasses, on our park benches, or pushing grocery cart filled with a hodgepodge of belongings, is what most people observe about the homeless. If you ever take the time to talk to one, or better yet a handful or more, you’ll never hear exactly the same story twice about how things got to be the ways things are. Some mention joblessness, domestic violence, addiction, or perhaps something I’m leaving out or a combination of these unpleasant circumstances. The homeless have reached the ultimate level of poverty in the United States. Possibly some are entirely to blame for their misfortunate or are exploiting every handout possible. Some homeless people will say that they don’t want help or that they prefer living on the street, but I see it more as they have received help and it didn’t work and that they’ve come to terms with it rather than go after a false-hope. This is a symptom of chronic homelessness. A tangible example of help that never worked is that there is currently about a forty-three year long waiting list for a studio apartment through the District of Columbia Housing Choice Voucher Program (formerly known as Section 8 Housing).1 Other frustrations could include struggling with an overpowering addiction or applying for a job at age 45 with a disability and resume saying that you dropped out in ninth grade. Despite these depressing situations various cities across the United States are making matters worse by passing legislation criminalizing homelessness. From a fiscal standpoint this makes no sense because it costs about three times as much to put someone in jail than it does to place someone in supportive housing according to the Federal Strategic Plan to End Homelessness, Congressional Budget Office, and the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness as shown in the graph below. 2 1 Wheeler, Candace. "For Many, D.C. Housing Waiting List Offers Little More than Hope." Washington Post. The Washington Post, 05 Nov. 2012. Web. www.washingtonpost.com/local/for-many-the-citys-housingwaiting-list-offers-little-more-than-hope/2012/11/04/e092348a-19f8-11e2-aa6f-3b636fecb829_story.html 2 Source: U.S. Interagency on Homelessness www.usich.org. 2 Despite this growing trend of criminalizing homelessness in the United States, it is nothing more than a quick-fix solution to remove homeless people from sight without thought for addressing the underlying causes of homelessness or an exit strategy for the homeless post incarceration. The National Coalition for the Homeless and the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty has identified the top twenty cities with the most anti-homeless legislation.3 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. Sarasota, Florida Lawrence, Kansas Little Rock, Arkansas Atlanta, Georgia Las Vegas, Nevada Dallas, Texas Houston, Texas San Juan, Puerto Rico Santa Monica, California Flagstaff, Arizona San Francisco, California Chicago, Illinois San Antonio, Texas New York City, New York Austin, Texas Anchorage, Alaska Phoenix, Arizona Los Angeles, California St. Louis, Missouri Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Examples of anti-homeless legislation includes Atlanta, Georgia, #4, has outlawed panhandling and supportive housing inside the city limits and Lawrence, Kansas, #2, has criminalized sitting on the sidewalk. These laws have targeted the homeless in a way that brings into question human rights violations. In Atlanta a Hurricane Katrina evacuee was arrested of asking for a few dollars outside a department store since it was in violation of their anti-panhandling law. The Helping Families Save Their Homes Act of 2009 signed by President Barack Obama requires the United States Interagency on Homelessness (USICH), an independent federal agency within the executive branch composed of nineteen cabinet secretaries and agency heads that coordinates the federal response to homelessness through national partnerships at every level on government and the private sector, to devise constructive alternatives to criminalization of homelessness. The first comprehensive federal legislative response was the McKinney-Vento 3 "National Coalition for the Homeless." National Coalition for the Homeless. Web. www.nationalhomeless.org/civilrights/crimpress2006.html. 3 Homeless Assistance Act of 1987 signed by President Ronald Reagan, created the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness and provided federal money for homeless shelter programs with special emphasis on assisting elderly persons, handicapped persons, and families with children, Native Americans, and veterans. Fortunately, the District of Columbia has not criminalized homelessness and instead made attempts to responsibly addressing people’s needs. The first comprehensive District of Columbia legislative response was the Homeless Services Reform Act of 2005 passed by Mayor Anthony Williams. Modeled after the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, this legislation established the DC Interagency on Homelessness (DCICH), facilitating interagency, cabinetlevel leadership in planning, policymaking, program development, provider monitoring, and budgeting for the Continuum of Care of homeless services. Considering the complexity and variety of experiences that led to homelessness, there is a consensus that it necessary to work multifaceted with government departments and agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and communities to alleviate the negative effects of homelessness on neighbors as well as the negative health outcomes that the homeless endure. To the left is a map of the Washington Metropolitan Area, shown below, demonstrating the serious problem with homelessness in the region. According to the annual Point-InTime Count conducted there were 13,205 people without homes, which is the eighth highest metropolitan in the country. 4 DCICH cabinet-level leadership includes: Chairman: City Administrator - Allen Y. Lew Agency Directors/District Officials Department of Human Services - David Berns Department of Mental Health - Stephen Baron Child and Family Services - Brenda Donald Department of Housing and Community Development - Michael Kelly Department of Health - Saul Levin District of Columbia Housing Authority - Adrianne Todman Department of Corrections - Thomas N. Faust Director of Employment Services - Lisa Mallory Office of the State Superintendent of Schools - Hosanna Mahaley Johnson District of Columbia Homeland Security and Emergency Management Agency Christopher Geldart Department of General Services - Brian J. Hanlon Metropolitan Police Department - Cathy Lanier (Diane Groomes) Fire and Emergency Medical Services - Kenneth B. Ellerbe (Ex-officio) District of Columbia Public Schools - Kaya Henderson Community Members - Representing the Homeless Donald Brooks Cheryl K. Barnes Brian Watson Scott McNeilly Nan Roman Margaret Riden Gary James Minter Continuum of Care Hilary Espinosa Polly Donaldson Kelly Sweeny McShane Jean-Michel Giraud Kimberly Black King Chapman Todd Sue Ann Marshall Michael Ferrell E. Schroeder Stribling Hannah M. Hawkins Deborah Shore Luis Vasquez Contact Information: Darrell Cason, DC Department of Human Services darrell.cason3@dc.gov 5 The alternative to criminalizing homelessness is to understand how people become homeless, while exploring policies that can be implemented to stabilize the homeless and prevent others from becoming chronically homeless in the future. Typically people become homeless by last resort. It starts will with a series of unfortunate circumstances. The individual or family loses their home and they either move in with a friend or family member. After an extended amount of time, they move into a shelter or onto the street. Below is list of leading reasons for homelessness.4 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Lack of Affordable Housing Low Paying Jobs/Loss of Job Physical or Mental Disability Alcohol Addiction Drug Dependence Family Issues/Domestic Violence Unemployment Poverty Prison Re-Entry Extended Illness Although homelessness has increased 13.1% from 2008-2012, chronic homelessness – having experienced repeated or lengthy episodes of homelessness or deep disabilities, has decreased by about 10% from 2008-2012. The District of Columbia has 6,954 homeless persons. Family homelessness has increased 73% from 2008-2012. This is shown in the graph and chart below. 4,500 Individuals & Persons in Families counted at Point in Time, 2008-2012 Persons in Individuals Families 2008 4,207 1,836 2009 3,934 2,294 2010 4,016 2,523 2011 3,858 2,688 2012 3,769 3,187 4,000 3,500 3,000 Individuals 2,500 2,000 Persons in Families 1,500 1,000 500 0 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 4 5 "Ten Causes of Homelessness Print PDF." Thrive DC. Web. 20 Nov. 2012. www.thrivedc.org/blog/ten-causes-of-homelessness. 5 Homeless in the District of Columbia: The Point in Time Enumeration. The Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness, 2012. Web. http://ich.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ich/publication/attachments/2012%20PIT%20Fact%20Sheet.pdf 6 6 Single Homeless People Homeless living in Families – most often headed by sole female adult • • 33% are chronically homeless • 14.5% have chronic health problems. 69% are chronically homeless • 29.1% have chronic health problems. • 25% formerly lived in foster care, jail, prison, hospital, substance abuse or psychiatric treatment facility in the past. • 23.7% are physically disabled. • 20% lived outside of the District of Columbia prior to becoming homeless. • 19.2% are employed. • 17.5% were formerly institutionalized. • 15.1% are chronic substance abusers. • An insignificant percentage formerly lived in foster care, jail, prison, hospital, substance abuse or psychiatric treatment facility in the past. • An insignificant percentage is physical disabled. • Most lived in Ward 7 or Ward 8 prior to becoming homeless. • 16.7% are employed. • 8.6% are formerly institutionalized. • 4.2% are chronic substance abusers. • 13.4% are U.S. Military Veterans. • An insignificant percentage is a U.S. Military Veteran. • 13.3% are mentally ill. • • 11.8% are a language minority. • An insignificant percentage is a language minority • Men are three times more likely than women to be single while homeless. • Average Male Age to be single while homeless: 48 • Women are about one-third as likely as men to be single while homeless. • Average Female Age to be single while homeless: 39 12.7% are severely mentally ill. • Women are four times more likely than men to be homeless living in a family. • Average Female Age to be homeless living in a family: 30 • Men are about one-fourth as likely as women to be homeless living in a family. • Average Male Age to be homeless living in a family: 33 Source: "The Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness." The Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness. Web. www.community-partnership.org/cp_dr-fastf.php. 7 Homeless Families vs. Single Homeless People Homeless families and single homeless persons are the two distinctly different groups each accounting for approximately equal proportions of the homeless population. As the facts on the previously page show homeless families statistically are better off in terms of health, wellbeing, and chances of overcoming homelessness, than single homeless persons. The ambiance of family or community promotes safety and security that is an essential pathway to creating more stable people. Something major to note is that women are four times more likely to be living with a family than men. Considering that there is a 73% growth in homeless families from 2008 and 2012 this is especially concerning. The majority of these homeless families once lived in Wards 7 and 8, where unemployment is 15% and 22% respectively,7 which is the highest in the District of Columbia and one of the highest in the United States. The District of Columbia is starkly different from the western to eastern quadrants of the city. In Northwest, specifically Wards 2 and 3, people enjoy prosperity in terms of income and education, while those living in Wards 7 and 8 are afforded the least social mobility. While affordable housing and jobs should be at the forefront of the homelessness debate, quality education should be close behind since it is one of the greatest equalizers in terms of providing opportunity to people. This will most help homeless families. Single homeless people may need additional services to deal with physical or mental disability and alcohol or drug addiction. Each situation is case by case. Considering that affordable housing, job creation, and quality education is expensive and largely more broad-sweeping policies, transportation costs are an immediate need of the homeless today. The homeless spend a significant portion of their day traveling throughout the District seeking resources. In an ideal world the homeless would not prioritize transportation, because there would be small, efficient operations throughout the District of Columbia that provide wraparound services such as healthcare, career resources, meal services, housing, counseling, and alcohol and drug resources/rehabilitation. Additional resources that may be helpful for further research include the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness (www.usich.gov), DC Interagency Council on Homelessness (www.ich.dc.gov), and the Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness (www.community-partnership.org). 7 "Falling D.C. Unemployment 'good News,' Not Great." The Washingtion Times. N.p., n.d. Web. <http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2012/sep/23/falling-dc-unemployment-good-news-not-great/>.