Meeting EAC Human Resource Needs

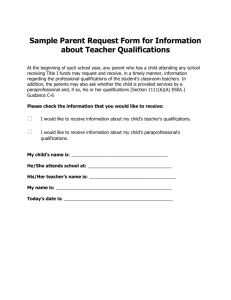

advertisement