Data Types

advertisement

Types

Aaron Bloomfield

CS 415

Fall 2005

1

Why have Types?

• Types provide context for operations

– a+b what kind of addition?

– pointer p = new object how much space?

• Limit valid set of operations

– int a = “string” know error before run time

2

Computer Hardware & Types

• Remember CS216?

– Bits in data are generally untyped

– Bits interpreted as having a type, such as:

• Instruction

• Address

• Floating-point number

• Character

• High-level language interprets bits

3

Type assignment

• Language-dependent

• a+b example again:

– Ada: a and b declared with static types

– Perl: $a and $b are dynamically typed

– Scheme: checked at run-time

– Smalltalk: checked at run-time

– Bliss: completely untyped

4

Static vs. Dynamic Typing

• First, what does strongly typed mean?

– Prevents invalid operations on a type

• Statically typed: strongly typed and type

checks can be performed at compile time

– Ada, Pascal: almost all type checking done at

compile time, with just a few exceptions

– C, C++, Java, Ocaml

• Dynamically typed: type checking is

delayed until run time

– Scheme, Smalltalk, Perl

5

Defining/Declaring a Type

• Fortran: variable’s type known from name

– Letters I-N = integer type

– Otherwise = real (floating-point) type

• Scheme, Smalltalk: run-time typing

• Most languages (such as C++): user

explicitly declares type

– int a, char b

6

Classifying types

• A type is either one of a small group of built-in

types or a user-defined composite

• Built-in types include:

–

–

–

–

–

Integers

Characters: ASCII, Unicode

Boolean (not in C/C++)

Floating points (double, real, float, etc.)

Rarer types:

• Complex (Scheme, Fortran)

• Rational (Scheme)

• Fixed point (Ada)

7

Number precision

• Is the precision specified by the type in the

language implementation?

– Java, C, C++ Fortran: user specifies precision

• Java: byte, short, int, long

– Most other languages: implementation

– Is the precision consistent across platforms?

• Java: Yes

• C/C++: No

8

Number precision

• If user doesn’t specify type, code can lose

portability due to differences in precision

– In C/C++, precision is platform-dependent

• Neat example in Haskell

–

2 ^ 200

1606938044258990275541962092341162602522202993782792835301376

– Support for infinite precision types

– Java provides BigInteger and BigDecimal for this

purpose

9

Type Equivalence

• Determining when the types of two

values are the same

struct student { string name; string

address;}

struct school { string name; string

address;}

• Are these the same?

be?

Should they

10

Structural Equivalence

• The same components, put together the same

way = same type

• Algol-68, early Pascal, C (with exceptions)

– And ML, somewhat

• Straightforward and easy to implement

• Definition varies from lang to lang

– eg. Does the ORDER of the fields matter?

• Back to example: are they the same?

struct student { string name; string address;}

struct school { string name; string address;}

• Yes, they are (with structural equivalence)

11

Name Equivalence

•

•

•

•

More popular recently

A new name or definition = a new type

Java, current Pascal, Ada

Assume that: if programmer wrote two different

definitions, then wanted two types

– Is this a good or bad assumption to make?

• Back to example: are they the same?

struct student { string name; string address;}

struct school { string name; string address;}

• No, they are not (with name equivalence)

12

Problem! Aliases

• Modula-2 example:

TYPE celsius_temp = REAL;

TYPE fahren_temp = REAL;

VAR c : celsius_temp;

f : fahren_temp;

…

f := c;

• Modula has loose name equivalence, so this is

okay

– But normally it probably should be an error

13

Types of Name Equivalence

• Strict: aliases are distinct types

• Loose: aliases are equivalent types

• Ada has both:

– type test_score is integer;

– type celsius_temp is new integer;

type fahren_temp is new integer;

• A derived type is incompatible with its parent type

• now f := c will generate an error

14

Type Conversion

• Conversion needed when certain types

are expected but not received

• a+b expecting either 2 ints or 2 floats

• Switching between types may result in

overflow

– example: floating-point integer

15

Coercion

• Can automatically force values to another

type for the given context

• a+b revisited:

– Without coercion, if both aren’t the same type

then there’s a compile-time error

– With coercion, if either is floating-point, then

addition is floating-point; otherwise int addition

• Issue: Things are happening without you

asking them to occur! Good/Bad?

16

Data Types

Records (Structures)

Variants (Unions)

Arrays

Sets

17

Records

• Also known as ‘structs’ and ‘types’.

–C

struct resident {

char initials[2];

int ss_number;

bool married;

};

• fields – the components of a record,

usually referred to using dot notation.

18

Nesting Records

• Most languages allow records to be

nested within each other.

– Pascal

type two_chars = array [1..2] of char;

type married_resident = record

initials: two_chars;

ss_number: integer;

incomes: record

husband_income: integer;

wife_income: integer;

end;

end;

19

Memory Layout of Records

• Fields are stored adjacently in memory.

• Memory is allocated for records based on

the order the fields are created.

• Variables are aligned for easy reference.

Optimized for space

Optimized for memory alignment

4 bytes / 32 bits

4 bytes / 32 bits

initials

(2 bytes)

married

(1 byte)

initials

(2 bytes)

ss_number

(4 bytes)

ss_number

(4 bytes)

married

(1 byte)

20

Simplifying Deep Nesting

• Modifying records with

become bothersome.

deep

nesting

can

book[3].volume[7].issue[11].name := ‘Title’;

book[3].volume[7].issue[11].cost := 199;

book[3].volume[7].issue[11].in_print := TRUE;

• Fortunately, this problem can be simplified.

• In Pascal, keyword with “opens” a record.

with book[3].volume[7].issue[11] do

begin

name := ‘Title’;

cost := 199;

in_print := TRUE;

end;

21

Simplifying Deep Nesting

• Modula-3 and C provide better methods

for manipulation of deeply nested records.

– Modula-3 assigns aliases to allow multiple openings

with var1 =

var2 =

DO

var1.name

var2.cost

END;

book[1].volume[6].issue[12],

book[5].volume[2].issue[8]

= var2.name;

= var1.cost;

– C allows pointers to types

• What could you write in C to mimic the code above?

22

Variant Records

• variant records – provide two or more

alternative fields.

• discriminant – the field that determines

which alternative fields to use.

• Useful for when only one type of record

can be valid at a given time.

23

Variant Records – Pascal Example

type resident = record

initials: array [1..2] of char;

initials

(2 bytes)

married

(1 byte)

husband_income (4 bytes)

case married: boolean of

true: (

husband_income: integer;

wife_income: integer;

);

false: (

income: real;

);

id_number: integer;

end;

wife_income (4 bytes)

Case is TRUE

initials

(2 bytes)

married

(1 byte)

income (4 bytes)

Case is FALSE

24

Unions

• A union is like a record

– But the different fields take up the same space within

memory

union foo {

int i;

float f;

char c[4];

}

• Union size is 4 bytes!

25

Union example (from an assembler)

union DisasmInst {

#ifdef BIG_ENDIAN

struct { unsigned char a, b, c, d; } chars;

#else

struct { unsigned char d, c, b, a; } chars;

#endif

int intv;

unsigned unsv;

struct { unsigned offset:16, rt:5, rs:5, op:6; } itype;

struct { unsigned offset:26, op:6; } jtype;

struct { unsigned function:6, sa:5, rd:5, rt:5, rs:5,

op:6; } rtype;

};

26

void CheckEndian() {

union {

char charword[4];

unsigned int intword;

} check;

check.charword[0]

check.charword[1]

check.charword[2]

check.charword[3]

=

=

=

=

Another union example

1;

2;

3;

4;

#ifdef BIG_ENDIAN

if (check.intword != 0x01020304) {

/* big */

cout << "ERROR: Host machine is not Big Endian.\nExiting.\n";

exit (1);

}

#else

#ifdef LITTLE_ENDIAN

if (check.intword != 0x04030201) {

/* little */

cout << "ERROR: Host machine is not Little Endian.\nExiting.\n";

exit (1);

}

#else

cout << "ERROR: Host machine not defined as Big or Little Endian.\n";

cout << "Exiting.\n";

exit (1);

#endif // LITTLE_ENDIAN

#endif // BIG_ENDIAN

}

27

Arrays

• Group a homogenous type into indexed

memory.

• Language differences: A(3) vs. A[3].

– Brackets are preferred since parenthesis are

typically used for functions/subroutines.

• Subscripts are usually integers, though

most languages support any discrete type.

28

Array Dimensions

• C uses 0 -> (n-1) as the array bounds.

– float values[10];

// ‘values’ goes from 0 -> 9

• Fortran uses 1 -> n as the array bounds.

– real(10) values

! ‘values’ goes from 1 -> 10

• Some languages let the

define the array bounds.

programmer

– var values: array [3..12] of real;

(* ‘values’ goes from 3 -> 12 *)

29

Multidimensional Arrays

• Two ways to make multidimensional arrays

– Both examples from Ada

– Construct specifically as multidimensional.

matrix: array (1..10, 1..10) of real;

-- Reference example: matrix(7, 2)

• Looks nice, but has limited functionality.

– Construct as being an array of arrays.

matrix: array (1..10) of array (1..10) of real;

-- Reference example: matrix(7)(2)

• Allows us to take ‘slices’ of data.

30

Array Memory Allocation

• An array’s “shape” (dimensions and

bounds) determines how its memory is

allocated.

– The time at which the shape is determined also

plays a role in determining allocation.

• At least 5 different cases for determining

memory allocation:

31

Array Memory Allocation

• Global lifetime, static shape:

– The array’s shape is known at compile time,

and exists throughout the entire program.

• Array can be allocated in static global memory.

• int global_var[30]; void main() { };

• Local lifetime, static shape:

– The array’s shape is known at compile time,

but exists only as locally needed.

• Array is allocated in subroutine’s stack frame.

• void main() { int local_var[30]; }

32

Array Memory Allocation

• Local lifetime, bound at elaboration time:

– Array’s shape is not known at compile time, and

exists only as locally needed.

• Array is allocated in subroutine’s stack frame and divided into

fixed-size and variable-sized parts.

• main() { var_ptr = new int[size]; }

• Arbitrary lifetime, bound at elaboration time:

– Array is just references to objects.

• Java does not allocate space; just makes a reference to

either new or existing objects.

• var_ptr = new int[size];

33

Array Memory Allocation

• Arbitrary lifetime, dynamic shape

– The array may shrink or grow as a result of program

execution.

• The array must be allocated from the heap.

• Increasing size usually requires allocating new memory,

copying from old memory, then de-allocating the old memory.

34

Memory Layout Options

• Ordering of array elements

accomplished in two ways:

can

be

– row-major order – Elements travel across

rows, then across columns.

– column-major order – Elements travel

across columns, then across rows.

Row-major

Column-major

35

Row Pointers vs.

Contiguous Allocation

• Row pointers – an array of pointers to an

array. Creates a new dimension out of

allocated memory.

• Avoids allocating holes in memory.

day[0]

day[1]

day[2]

day[3]

day[4]

day[5]

day[6]

S

u

n

d

a

y

d

a

y

T

u

M

o

n

e

s

d

a

y

W

e

d

n

e

s

d

a

y

T

h

u

r

s

d

a

y

F

r

i

d

a

y

S

a

u

r

d

a

y

t

Array =

57 bytes

Pointers =

28 bytes

Total Space =

85 bytes

36

Row Pointers vs.

Contiguous Allocation

• Contiguous allocation - array where each

element has a row of allocated space.

• This is a true multi-dimensional array.

– It is also a ragged array

S

u

n

d

a

y

M

o

n

d

a

y

T

u

e

s

d

a

y

W e

d

n

e

s

d

a

T

h

u

r

s

d

a

y

F

r

i

d

a

y

S

a

t

u

r

d

a

y

y

Array = 70 bytes

37

Array Address Calculation

• Calculate the size of an element (1D)

• Calculate the size of a row (2D)

– row = element_size * (Uelement - Lelement + 1)

• Calculate the size of a plane (3D)

– plane = row_size * (Urows - Lrows + 1)

• Calculate the size of a cube (4D)

:

:

38

Array Address Calculation

• Address of a 3-dimenional array A(i, j, k) is:

address of A

+ ((i - Lplane) * size of plane)

+ ((j - Lrow)

* size of row)

+ ((k - Lelement) * size of element)

A

A(i)

A(i, j)

A(i, j, k)

Memory

39

Sets

• Introduced by Pascal, found in most recent

languages as well.

• Common implementation uses a bit vector

to denote “is a member of”.

– Example:

U = {‘a’, ‘b’, …, ‘g’}

A = {‘a’, ‘c’, ‘e’, ‘g’} = 1010101

• Hash

tables

needed

implementations.

for

larger

– Set of integers = (232 values) / 8 = 536,870,912 bytes40

Enumerations

41

Enumerations

• enumeration – set of named elements

– Values are usually ordered, can compare

enum weekday {sun,mon,tue,wed,thu,fri,sat}

if (myVarToday > mon) { . . . }

• Advantages

– More readable code

– Compiler can catch some errors

• Is sun==0 and mon==1?

– C/C++: yes; Pascal: no

• Can also choose ordering in C

enum weekday {mon=0,tue=1,wed=2…}

42

Lists

43

Lists

• list – the empty list or a pair consisting of an

object (list or atom) and another list

(a . (b . (c . (d . nil))))

• improper list – list whose final pair contains two

elements, as opposed to the empty list

(a . (b . (c . d)))

• basic operations: cons, car, cdr, append

• list comprehensions (e.g. Miranda and Haskell)

[i * i

|

i <- [1..100]; i mod 2 = 1]

44

Recursive Types

45

Recursive Types

• recursive type - type whose objects may

contain references to other objects of the

same type

– Most are records (consisting of reference

objects and other “data” objects)

– Used for linked data structures: lists, trees

struct Node {

Node *left, *right;

int data;

}

46

Recursive Types

• In reference model of variables (e.g. Lisp,

Java), recursive type needs no special

support. Every variable is a reference

anyway.

• In value model of variables (e.g. Pascal,

C), need pointers.

47

Value vs. Reference

• Functional languages

– almost always reference model

• Imperative languages

– value model (e.g. C)

– reference model (e.g. Smalltalk)

• implementation approach: use actual values for

immutable objects

– combination (e.g. Java)

48

Pointers

• pointer – a variable whose value is a

reference to some object

– pointer use may be restricted or not

• only allow pointers to point to heap (e.g. Pascal)

• allow “address of” operator (e.g. ampersand in C)

– pointers not equivalent to addresses!

– how reclaim heap space?

• explicit (programmer’s duty)

• garbage collection (language implementation’s

duty)

49

Value Model – More on C

• Pointers and single dimensional arrays interchangeable,

though space allocation at declaration different

int a[10]; int *b;

• For subroutines, pointer to array is passed, not full array

• Pointer arithmetic

– <Pointer, Integer> addition

int a[10];

int n;

n = *(a+3);

– <Pointer, Pointer> subtraction and comparison

int

int

int

int

a[10];

* x = a + 4;

* y = a + 7;

closer_to_front = x < y;

50

Dangling References

• dangling reference – a live pointer that

no longer points to a valid object

– to heap object: in explicit reclamation,

programmer reclaims an object to which a

pointer still refers

– to stack object: subroutine returns while some

pointer in wider scope still refers to local

object of subroutine

• How do we prevent them?

51

Dangling References

• Prevent pointer from pointing to objects

with shorter lifetimes (e.g. Algol 68, Ada

95). Difficult to enforce

• Tombstones

• Locks and Keys

52

Tombstones

• Idea

– Introduce another level of indirection: pointer contain the address of the

tombstone; tombstone contains address of object

– When object is reclaimed, mark tombstone (zeroed)

• Time overheads

– Create tombstone

– Check validity of access

– Double indirection

• Space overheads

– when to reclaim??

• Extra benefits

– easy to compact heap

– works for heap and stack

53

54

Locks and Keys

• Idea

– Every pointer is <address, key> tuple

– Every object starts with same lock as pointer’s key

– When object is reclaimed, object’s lock marked (zeroed)

• Advantages

– No need to keep tombstones around

• Disadvantages

– Objects need special key field (usually implemented only for

heap objects)

– Probabilistic protection

• Time overheads

– Lock to key comparison costly

55

56

Garbage Collection

• Language implementation notices when

objects are no longer useful and reclaims

them automatically

– essential for functional languages

– trend for imperative languages

• When is object no longer useful?

– Reference counts

– Mark and sweep

– “Conservative” collection

57

Reference Counts

• Idea

– Counter in each object that tracks number of

pointers that refer to object

– Recursively decrement counts for objects and

reclaim those objects with count of zero

• Must identify every pointer

– in every object (instance of type)

– in every stack frame (instance of method)

– use compiler-generated type descriptors

58

Type descriptors example

myFunc type descriptor at 0x104

public class MyProgram {

public void myFunc () {

Car c;

}

}

i

offset

address

0

0 (Car)

0x018

Car type descriptor at 0x018

public class Car {

char a, b, c;

Engine e;

Wheel w;

}

public class Engine {

char x, y;

Valve v;

}

i

offset

address

0

4 (Engine)

0x0A2

1

5 (Wheel)

0x005

Engine type descriptor at 0x0A2

i

offset

address

0

3 (Valve)

0xB05

public class Wheel {...}

public class Valve {...}

Wheel type descriptor at 0x005

Valve type descriptor at 0xB05

59

Mark-and-Sweep

•

Idea

… when space low

1. Mark every block “useless”

2. Beginning with pointers outside the heap,

recursively explore all linked data structures

and mark each traversed as useful

3. Return still marked blocks to freelist

•

Must identify pointers

– in every block

– use type descriptors

60

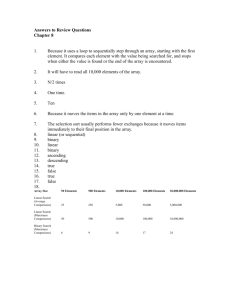

Garbage Collection Comparison

• Reference Count

– Will never reclaim

circular data structures

– Must record counts

• Mark-and-Sweep

– Lower overhead

during regular

operation

– Bursts of activity

(when collection

performed, usually

when space is low)

61

Conservative collection

• Idea

– Number of blocks in heap is much smaller than number of

possible addresses (232) – a word that could be a pointer into

heap is probably pointer into heap

– Scan all word-aligned quantities outside the heap; if any looks

like block address, mark block useful and recursively explore

words in block

• Advantages

– No need for type descriptors

– Usually safe, though could “hide” pointers

• Disadvantages

– Some garbage is unclaimed

– Can not compact (not sure what is pointer and what isn’t)

62