Overview of RWS100

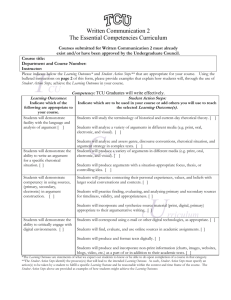

advertisement

Session 1: Welcome 9.30: Intro to RWS100 and the lower division writing program TA Introductions; photo session (program of assimilation and mind control revealed) Overview of RWS100 10.00: Overview of RWS100 The program, RWS100, ITC, Fall students, expectations, assignments, and options. RWS 100 and the lower division writing program See the handout for contact info A lot of material on the wiki (let us know if you need help finding) Argument is at the center of the writing program/100. We mostly focus on non fiction, argumentative texts. RWS 100 and the lower division writing program We ask students to interpret, analyze, evaluate and produce written arguments, because this is central to academic literacy, critical thinking, and civic life - Lasch: “argument is the essence of education,” and “central to democratic culture”; - Norgaard: Universities are “houses of argument.” - Graff: “Argument literacy” is key to higher education. We want students to be able to identify claims, evaluate evidence and reasons, locate assumptions, identify argumentative moves, pose critical questions, produce sophisticated arguments, etc. We do this not only because it’s good for their souls, critical thinking, ability to reason, deliberate, be engaged citizens, etc. But also because it’s key to their professional futures – every gateway requires it. Why We Fight! (4 your right to write, argue & analyze well) The ability to interpret arguments, locate claims and evidence, analyze moves and strategies, and evaluate arguments are crucial skills. They are central to business, law, professional life, and to academic study (including graduate school). Students tested for these skills in the WPA, the LSAT, GMAT, and GRE – all the gateways to professional life. Consider the LSAT… Sample LSAT Question FIND THE MAIN CLAIM Pediatrician: “Some parents have decided not to have their children receive the MMR vaccine because they fear that it may cause autism. They cite a study that found a possible link between the vaccine and the disease. However, two other much larger studies have found no link between the MMR vaccine and autism. These parents have, therefore, willfully put their own children and many others at risk of catching measles, mumps, and rubella, while failing to do anything to prevent their children from becoming autistic.” Which most accurately expresses the main claim of the pediatrician’s argument? (A) Parents should not pay attention to medical studies because they can’t understand them; instead, they should get advice from their pediatricians. (B) The study that found a link between autism and the MMR vaccine was unsound because the doctor who conducted it was being paid by a group of trial lawyers who wanted him to find a connection so they could carry out a lawsuit. (C) Public health needs require that parents have their kids vaccinated regardless of their fears about the procedure. (D) Parents’ refusal to have their kids take the vaccine is both medically unjustified and dangerous, because the vaccine has known disease-preventing benefits and refusing it will have no effect on whether their kids become autistic. (E) Despite the results of the two large studies, there is still some possibility that the MMR vaccine might cause autism. Analytical Writing Tasks Present Your Views on an Issue (45 minutes, choice of 2 topics) Analyze an Argument (30 minutes) Each essay is scored on a 0-6 scale using holistic scoring Two scores for each essay GRE Website presents directions, actual topics, scoring guide, and sample essays for both the Issue and Argument tasks (www.gre.org/gentest.html) Argumentation/Justification • In Wolfe’s 2010 study, assignments from a broad range of disciplines were collected and examined. Results? “A majority of writing assignments (59%) required argumentation. All engineering writing assignments required argumentation, as did 90% in fine arts, 80% of interdisciplinary assignments, 72% of social science assignments, 60% of education assignments, 53% in natural science, 47% in the humanities, and 46% in business. Argumentation is valued across the curriculum. • Example: Stockton found that the history faculty she interviewed unanimously, “agreed that argument is the key word for good writing and that the absence of argument constitutes the central problem in students’ written work” (Wolfe, p. 50). This finding was echoed in other fields. • Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa’s Academically Adrift, a comprehensive review of undergraduate education, identifies lack of argumentation skills as a major problem. (They also show that liberal arts degrees produce some of the most literate, sophisticated thinkers) • The Common Core State Standards Initiative of the National Governors’ Association – argument=key. • These aren’t so much “justifications” of our approach as points you may want to share with students, future employers, other academics who sometimes think teaching writing = comma placement. You will (not) be assimilated… You need to work within the course framework and assignment sequence, but you can be creative and adapt it – we’re interested in hearing your ideas (esp. for the start and end of the semester). RWS100 represents just one way to design a writing course – many others are possible (genre, critical literacy, cultural studies, expressivism, etc.) Writing programs often serve many masters, since general education programs are collaborative enterprises. Had we world enough and time (and money and control) I like the idea of a hybrid WID-based approach. You will (not) be assimilated… But even so, your experience in this program will be valuable as a) it’s an influential model, b) the trend is toward aligning k-12 and higher ed. around argument, and c) SDSU’s program is regionally influential. Our program is fairly “mainstream.” Our mission statement and learning outcomes are similar to WPA and NCTE statements on teaching writing. CSU-wide articulation efforts shaped by work at SDSU. You will (not) be assimilated… In other words, in the future, you may go on to teach writing in an entirely different way – and that’s great. But it will be useful to have familiarity with a program like this, which is large, multi-leveled, comprehensive and tightly designed. This semester there will be more opportunity to customize texts and assignments. We’ve assigned short texts you can supplement, as there will be more focus on evaluation of strengths and weaknesses. ITC: Expectations ITC = an important part of your work. You are expected to attend. You get credit for it. Wednesdays @ 1.00 – 1.50 in AH 2103 More importantly, it’s part of collaboration, professional development, and networking. Modest home work is assigned but it’s all to prepare for your class. Meetings are 50 minutes. Your contribution is important and most welcome. We provide a lot of support, but you are welcome to adapt & remix, or add your own materials. TA contributions have improved 100 a lot – many TA ideas are on the wiki. Teaching in a time of budget cuts… Class sizes are 30 - big for a writing class Most professional organizations say writing classes should have at most 20 students. Our pedagogies aren’t really designed for classes this big. We may wish to share coping strategies. We may want to “jigsaw” the work of preparing class plans, etc. You will likely teach RWS200 next semester, where learning curve is steeper, and you may benefit from the support of your fellow TAs. Meet your audience Fall semester students are often quite well prepared. Some may be fairly sophisticated writers, but you’ll be presenting them with a new, challenging way of approaching texts You may have some 3rd semester students who have come through 92a and 92b. If you do, roster will say level “1,” as opposed to “0”. They register late, tend to come in clusters, will be weaker writers; some will be ESL. You may have some ESL/international students. You can refer them to LING100 if you think they’ll struggle. About 500 students will have done “early start” classes over summer as college prep. They tend to be serious, hard working students, and are often grouped in a few classes. Main Texts 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Diamond, Carey, LaPierre/Harris RWS 100 Reader Graff et al. They Say/I Say: The Moves That Matter in Academic Writing. Little Seagull Handbook Short texts in the Reader: Kristof, Rifkin, Parry, etc. You can select your own, and other short texts on the wiki. Use to introduce the course/key concepts Texts for unit 2 and 3– you can select, or use ones on wiki. Some texts can be used repeatedly. E.g. you may wish to consider Parry’s “The Art of Branding a Condition” for introducing rhetoric, and also in the strategies unit. • • • • BUT - in a sense the “central” text in the class = the students’ texts. (Your fabulous teaching performance vs. their written performance) You may want to delve deep into the issues raised in texts. You may want to perform brilliantly, and model your teaching on the last class you took (a grad class). Student writing is the key text, and teaching them how to read their own writing practices (reflexivity) is important “The ability to reflect on what is being written seems to be the essence of the difference between able and not so able writers from their initial writing experience onward”(Yancey 4) Assignment Sequence 1. produce an account and analysis of a single argument (Diamond) 2. gather sources, situate an argument within a field of other texts, map out and analyze relationships between them (extend, complicate, illustrate, etc.) (Carey) 3. identify, analyze and evaluate rhetorical strategies LaPierre/Harris 4. an optional 4th assignment Optional Final Assignment (Assignment 3.5/4) ■ For the final assignment, you can select from a number of options. We recommend one of the following, although you are welcome to suggest alternatives. ■ Some TAs chose to extend the strategies assignment – so 3 & ½ major assignments. They do a formal written strategies assignment, plus a presentation (sometimes in groups) and self analysis of rhetorical choices. Assignment Options 1. Portfolio: Students have done small writing assignments over the semester. You can assign further short writing assignments in the final part of the course, and give students an aggregate grade for the completed portfolio. 2. Reflection essay – have students write a paper that asks them to reflect on the writing work they have done, what they have learned, the way they approach writing, the things they still need to work on, etc. Managing the Final Paper 3. Group projects/presentations where students get to make an argument that draws from one of the issues raised in the class, or which focuses on one of the texts covered. If you choose this option, we suggest you construct a group assignment with clearly defined roles for each student, so that individual grades can be assigned and you minimize “free riding” and conflict. 4. Lens paper: the “traditional” 4th assignment was to use the “lens assignment” (see past 100 syllabi, assignments, materials etc. for details.) This paper involves taking one of the texts we’ve read and using it as a “lens” through which to analyze another text or a contemporary issue. The student can present an original argument, interpretation or analysis. (e.g. “Characteristics of Demagoguery” and Wallace or LaPierre.) 5. Roll your own assignment Overview of RWS100 Sample syllabi, schedules and assignment sequences are on the wiki 11.00 The First Week(s): The first day: crashers, scheduling, class management (Jamie) 11.30 Reading Diamond Glen McClish 12.30-1.00 Admin 1.00 – 2.00 LUNCH 2.00 – 3.30 • Introducing rhetoric, the course, and working with short texts • Overview: common classroom activities Common Class Activities & Patterns [See p. 3 of handout] Pre-reading and “pre-discussion” work (questionnaires to get at assumptions, surveys, etc.) “Jig saw” work (students share researching key parts of text and share in class) Class discussion, group work Critical reading/rhetorical reading – posing questions, interrogating assumptions, reading actively and critically (modeling qns to ask) Charting – what is the text doing; what/how/why moves are made PACES (project, argument, claims, evidence, strategies) Pre-writing exercises + templates, rhetorical precis, metadiscourse, transitions, quotations, mechanics Drafting, peer review, student “read alouds,” conferencing Assessment and response Analysis (single argument, relationship between texts, strategies, “lens” work, evaluation of arguments) and presentation of student arguments Reflection and reflective practice (applying concepts to students own writing – e.g. charting, analyzing students’ moves and strategies, etc.) Example: pre-reading exercises 1. In Class test “Careful, you might run out of planet: SUVs and the exploitation of the American myth,” by Goewey. Questions: 1. Is Goewey critical or complimentary of SUVs? 2. Does the author believe that there is time to make a change? 3. Does the author put more emphasis on car quality or social issues in assessing the value of SUVs? 4. Is the author likely to be a supporter of major oil companies? 5. Was this essay written in 1979, 1989, or 1999? Pre-reading Examining Titles Carefully: Chua - Chua’s article “A World on the Edge” is part of her book World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability. Consider the Source: “A Variety of Religious Experience” is a chapter from a book titled The Meaning of Sports: Why Americans Watch Baseball, Football, and Basketball, and What They See When They Do Surveys/Questionnaires ■ Diamond asks why Eurasian peoples, rather than peoples of other continents, conquered much of the world. What factors do you think are relevant - how would you rank Geography, Culture, Natural resources, Intelligence, Institutions, Religion? ■ Why did the Spanish come to invade and take over South America, rather than the other way around? What were the key factors that allowed a relatively small group of Spanish soldiers to do this? ■ Do you agree with the statement that regarding a civilization’s ability to gain power, wealth, and strength, “...what’s far more important is the hand that people have been dealt, the raw materials they’ve had at their disposal.” Why or Why not? Always, or at certain points in history? ■ Etc. 2. Modeling close reading strategies – annotating, posing questions, reading actively and critically. Unit 1: Common Activities cont. 3. Charting – what is the text doing (what, how, why moves are made). Students chart their own and their peers’ writing Showing that this claim really is in the text, and why E. makes it. An important part of Ehrenreich’s argument is that the poor are invisible to affluent people. She suggests that the affluent “are less and less likely to share public spaces and services with the poor,” that political parties are unwilling to “acknowledge that low-wage work doesn’t lift people out of poverty” (217) and that media attention focuses more on “occasional success stories” than on the rising numbers of poor and hungry people (218). The fact that the poor are invisible contributes to the lack of attention that the problem of low wages is getting. Writer telling reader one piece of E.’s argument, one claim. Explaining why the “invisibility claim” is significant Common Activities cont. 4. PACES (project, argument, claims, evidence, strategies) Identifying claims – a good rule of thumb is to look for the following cues: - question/answer pattern - problem/solution pattern - self-identification (“my point here is that…”) - emphasis/repetition (“it must be stressed that…”) - approval (“Olson makes some important and long overdue amendments to work on …”) - metalanguage that explicitly uses the language of argument (“My argument consists of three main claims. First, that…”) Identifying and sorting claims Common Activities cont. Drafting: models, outlines, templates, rhetorical precis; metadiscourse, quotations 6. Drafting: peer review, workshops, review plans, student “read-alouds,” conferencing 7. Assessment and response 8. Reflection and reflective practice (applying concepts to students own writing – e.g. charting, analyzing students’ moves and strategies, etc.) 5. They Say/I Say Templates – verbs for talking about arguments Templates: The Graff & B Template One of our templates There are handouts, class exercises, and class plans based on each of these key activities (see wiki or Blackboard). Introducing rhetoric We ask that you tell students that RWS 100 is a rhetoric class. Some may base their expectations on high school English classes/literary analysis. Emphasize that the interpretation, analysis and production of argument is central, that they will be reading non-fiction texts, doing a lot of analysis. You may find “Content is king” - locate, remember and deliver content. You may encounter a “textbook mentality” in the reading practices of many of your students, and an “information processor” model of writing. Textbooks are often “anti-rhetorical” - presenting knowledge in terms of a decontextualized, disembodied voice of authority, a “view from nowhere,” and of knowledge as “settled,” unified and authoritative The contested, contingent, contextual, community-centered, argument-driven…in short, the RHETORICAL dimensions of knowledge – of academic discourse, are largely absent. Nudging students toward a rhetorical stance… We want to move students from a focus on what texts say (content) to what they do and how they do it (rhetoric). Rhetorical self consciousness = achieving a kind of double vision – of looking “at” as well as through language. Rhetorical self consciousness – understanding what texts do - is an important skill for students. Revealing the rhetorical moves that writers make, the strategies they draw on, is part of achieving academic literacy, and of acculturation into disciplinary communities. When you recognize the moves you not only understand the disciplinary conversation better, you are better equipped to join it. In the first week of class we’d like you to introduce key concepts through the analysis of some short texts. There is a folder on Blackboard to help you with this. Focusing on strategies and what texts do = good ways of introducing rhetoric. Basic Rhetorical Strategies How do texts position readers? What point of view do they adopt? From what perspective do they invite us to view the world? Consider these chewing gum ads: Rhetoric Is “Everywhere” & an “Everyday” Thing When a politician tries to get you to vote for them, they are using rhetoric. When a lawyer tries to move a jury, they are using rhetoric. When a government produces propaganda, they are using rhetoric. When an advertisement tries to get you to buy something, it is using rhetoric. When the president gives a speech, he is using rhetoric. But rhetoric can be much subtler (and quite positive) as well: When someone writes an office memo, they are using rhetoric. When a newspaper offers their depiction of what happened last night, they are using rhetoric. When a scientist presents theories or results, they are using rhetoric. When you write your mom or dad an email, you are using rhetoric. Thought itself is rhetorical - when you think, you engage in “inner argument,” or “inner persuasion” in order to reach a decision or act. HEADLINES DESCRIBING MEDICAL MARIJUANA DECISION Salon Magazine “Court rules against pot for sick people” New York Times: “High Court Allows Prosecution of Medical Marijuana Users” USA Today: “MEDICAL MARIJUANA BAN UPHELD” San Diego Union Tribune: “Court OKs Marijuana Crackdown” L.A. Times: “Justices Give Feds Last Word on Medical Marijuana” Christian Science Monitor: “US Court Rules Against Pot For Sick People” Christian News Source: “Medical Marijuana Laws Don't Shield Users From Prosecution” Telemarketing Strategies Script Pre-introduction: (Ask to speak to the decision-maker) Introduction: (Introduce yourself and the reason for your call) Attention Getter: (Mention the key features of the offer and qualify them for eligibility) Probing Questions: (Always ask for information that will be useful for rebuttals) Offer: (Explain the product/service and terms of commitment) Close: (ALWAYS ASK FOR THE SALE) Rebuttal (deal with objections) Sales Continuation: (Agree, use rebuttals, sell benefits, CLOSE) Up/down/cross-sell: (If there is another product of less-price this is the time to sell it.) Confirmation Close: (Review the terms of the offer to reduce buyer remorse) Final Close: (End on a positive note. Thank the customer and leave a dial free number for customer support) Everyday words, names, definitions, categories – how they are selected or constructed = rhetorical. Consider: Cash advance (vs. high interest loan) Second Mortgage vs. Home equity loan “War on terror,” vs. “war against Islamic extremists,” vs. “fight against Al Queda” (scope, agents involved, action) “The 1%,” “job creators” Military contractors, mercenaries “War on drugs”’ “Axis of Evil”; “Body bags” vs. “transfer tubes” “Doctor assisted suicide” vs. “death with dignity” “Defense of marriage” vs. “marriage equality” “French Fries/Freedom fries” “Death Tax/Estate Tax” “Habit forming” vs. “addictive” “Erectile dysfunction” vs. “impotence” “Halitosis” vs. “bad breath” “Male pattern baldness” vs. “losing your hair” “Viagra!” Common expressions reveal rhetorical moves “TO BE HONEST/FRANK/FRANKLY/TO TELL YOU THE TRUTH..” "Parrhesia" or "sincere style.” Most common strategies: False sincerity (sales pitch) To establish intimacy/insider status (because we are close, I can confide in you). To signal seriousness. To signal shift to serious topic – politeness or performance is being set aside in favor of frankness To establish emphasis. I want to really emphasize what comes next. E.g. Obama & “look” as emphasis marker. He’ll say to audiences, “Look, the reality is…” = I’m dropping out of performance mode and speaking to you plainly and seriously. Confess to potentially unpopular position, and manage “face” - may effect other’s opinion of you (status-threatening) (“To be honest, I voted for Ralph Nader in 2000; “To be honest, I thought Paradise Lost was a bore.” "To tell you the truth, I'm not going to make the deadline." When ads used a lot of logos Today’s ads often use different appeals WE CAN READ MATERIAL CULTURE RHETORICALLY “By reading…we mean something more than simply lifting information out of books and articles. To read a text or event is to do something to it, to make sense out of its signals and clues…Reading is thus not something we do to books alone. Or, to put it another way, books and other printed surfaces are not the only texts we read. Rather, a ‘text’ is anything that can be interpreted, that we can make meaning out of or assign value to. In this sense, all culture is a text and all culture can be read.” Joseph Harris and Jay Rosen. Strategies in Sculpture: Maya Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial Why these choices for a memorial – what strategies might they represent? The Vietnam war memorial is black It is made of reflective black granite. When a visitor looks at the wall, she will see the engraved names and her own reflection The monument is built along a pathway that requires people to move along the small corridor of space Unlike many monuments, it lists all the names of U.S. soldiers who died, and it does so in chronological rather than alphabetic order (Lin has she wanted the wall to read “‘like an epic Greek poem’ and ‘return the vets to the time frame of the war’) Information about rank, unit, and decorations are not given The wall is V-shaped, with one side pointing to the Lincoln Memorial and the other to the Washington Monument. Lin's conception was to create an opening or a wound in the earth to symbolize the gravity of the loss of the soldiers The rise of the “bum-proof” bench in Los Angeles "One of the most common, but mindnumbing, of these deterrents is the [L.A.] Rapid Transit District’s new barrelshaped bus bench that offers a minimal surface for uncomfortable sitting, while making sleeping utterly impossible. Such ‘bumproof’ benches are being widely introduced on the periphery of Skid Row. Another invention...is the aggressive deployment of outdoor sprinklers. Several years ago the city opened a ‘Skid Row Park’ along lower Fifth Street, on a corner of Hell. To ensure that the park was not used for sleeping--that is, to guarantee that it was mainly utilized for drug dealing and prostitution--the city installed an elaborate overhead sprinkler system programmed to drench unsuspecting sleepers at random times during the night. The system was immediately copied by some local businessmen in order to drive the homeless away from adjacent public sidewalks.“Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles, p. 233. Introducing rhetoric You may wish to use short texts, visual texts, advertisements, op-eds and other texts that students are probably familiar with in order to introduce rhetoric. Email communication is a good place to start – students are familiar with the genre, and may find it easier to recognize strategies, acts of persuasion, positioning, performance, etc. This YouTube animation is a good text to start a discussion about rhetoric – about audience, purpose, persuasion, strategies, genre, ethos, rhetorical situation, etc. Using a YouTube Animation to introduce rhetorical concepts SubText – animation showing a guy composing an email to a girl he likes. The man “thinks aloud” as he writes, and we glimpse what goes on “in his head” as he composes http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=400w4XnjElI Examine how this trivial act is full of rhetorical issues. The character is asking, how does this language present me? What persona does it construct? What tactic will be most effective? What moves should I make, how will this make me seem? How should I think of my audience? What is my purpose? How do I avoid embarrassment? Have students take the concepts of rhetorical situation, persuasion, construction of ethos, strategies, etc., and apply to this visual text. Rewrite these rhetorically tone deaf student emails “Hey prof, sorry I didn’t turn in my paper yesterday in class. I had a science test to study for that was really important. Is there any way I can turn it in late just this once? Let me know by tonight that way I don’t waste my time doing it if you won’t.” “Dear professor, I am writing you cuz unfortunately I won’t be able to make it to our appointment today. yesterday was my 21st bday and I’m still hangover and don’t think I should drive. let me know when you can make another appointment.” List strategies Introduce self Apologize Take responsibility Establish ethos Elicit sympathy/pathos Build a defense Present evidence (doctor’s note, note from coach, etc.) Initiate action/repair Etc. Charting & Analyzing Sample Short Texts. Rifkin and Kristof Sample syllabi, schedules and assignment sequences are on the wiki. Reader contains plagiarism “agreement” – should also be section covering this in syllabus. Schedule some evaluation/feedback fairly early Outcomes should be listed on your syllabus, and it’s useful to include them in your assignments They can be used as part of student reflections, and to help prime students for evaluations. Learning Outcomes: What they are, why they matter, how to use them to your advantage. If things get ugly, the outcomes and syllabus provide you with backup. In disputes, they matter. Our outcomes are now explicitly framed in terms of the general education program and its “capacities” and goals (meta-outcomes) This language adds a certain amount of institutional authority to your course. You can point students to the section that states how important our courses and outcomes are to the educational mission of the university (i.e. the university’s carefully researched conclusion as to what constitutes “essential undergraduate academic skills.”) Discussion & Participation Prime with a questionnaire, survey or questions Call by name Put in groups and assign responsibility Jig saw work “Pyramids” (alone, in pairs, 4s, etc.) Freewrite (give students time to assemble thoughts, so they feel more confidant contributing Wait….at least 7 seconds. Try not to get stuck in the habit of answering your own questions. Have students post responses and homework to Blackboard, so you can bring to class and use to get discussion going. Author Interview, Panel or Role-Playing One student assumes the role of the writer and answers question from the audience about the article’s main claim, choices regarding supporting evidence, and the writer’s view of his/her audience at the time of writing. Students assigned to play role of author for 10-15 minutes. You may choose to let that student greet the class “in character,” and provide a brief summary of the argument that he/she wrote, which everyone else in class has read. After that, the exercise consists of class members asking the “writer” questions about the argument itself. CAN ALSO be used with assignment 2 (sources) in which students are responsible to assume the role of different authors, and you can set up a debate with Pinker. Seth Taylor’s Seven Tips for Discussion 1) Beware of cold starts. Consider directed freewriting, journaling, or the “Brain Dump” at the start of class. Quick responses can both kickstart discussions, and eventually help students question where their responses come from. 2) Be wary of asking the BIG questions first: “So… what do you think about the reading?” “So what’s the point of the chapter?” Active Learning: Seven Tips for Discussion 3) Let your first question be easy, possibly about their reading process: “How long did it take to read this?” “Where does it get interesting (or boring)?” Were there any passages you found difficult, interesting or unusual? 4) Open-ended questions will require students to think. Yes/No questions require very little of them, and can often shut down discussion before it starts. Active Learning: Seven Tips for Discussion 5) Encourage students to explain, support, their responses to a text. Almost every answer can be followed up with a “Why?” question from the instructor. Active Learning: Seven Tips for Discussion 6) Encourage students to talk to each other, rather than simply fire answers back to you: Re-directing students to respond to each others ideas Group breakout exercises Let students teach Active Learning: Seven Tips for Discussion 7) At the end of class, try to re-cap or summarize the ground that was covered. You do not need the discussion to come to a grand conclusion, but some sort of review will help increase retention. 4.00 Surviving the First Day • Classroom Dynamics • What to do on the First Day • The inside scoop from your fellow TAs