Here - WordPress.com

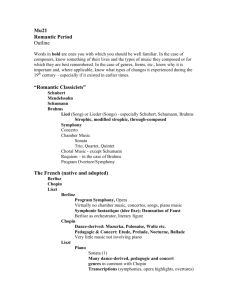

advertisement

Kristine Nowlain, soprano Senior Voice Recital, 4/7/2012 Program Notes Für Männer uns zu plagen (1782) by Corona Schröter, text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) Born into a musical family in Guben, Poland in 1751, Corona Schröter’s family moved to Leipzig, Germany in 1763 after years of touring. There she studied music theory, languages, and vocal technique with Johann Adam Hiller, who was frustrated with the lack of education available to women. She was also a gifted student of acting and painting. With musical talents that surfaced early on and a touring schedule comparable to Mozart’s childhood touring, her voice was slightly damaged but not so much that it kept her from singing throughout her whole life to great acclaim. In 1776 she moved to Weimar, Germany, when poet and author Johann Wolfgang van Goethe came to Leipzig to offer her a job in Weimar as Höfsangerin (court singer) in the court of Duchess Anna Amalia. She was offered a generous and steady salary, rare for a woman. It kept her financially independent and living comfortably until the end of her life. Schröter’s move to Weimar was the beginning of a great friendship with Goethe, as she acted in many of his works in the city’s Privattheater and they saw each other almost daily between 1776 and 1783. After 1782, she began to focus primarily on composing, producing nearly 400 vocal works (most of them lost). She collaborated with Goethe on the Singspiel, Die Fischerin (The Fisherwoman), writing all the incidental music and starring as the leading role of Dortchen, the fishergirl of the work’s title. The opening song, Der Erlkönig, predates Franz Schubert’s famous – and dramatically different – setting of the same text by 30 years. Für Männer uns zu plagen (For Men We Torment Ourselves) was the second song in this dramatic Singspiel, and conveys the character’s frustrations toward her father and husband. In this scene complex (a continuous musicodramatic work made up of smaller units of music and dialogue), Dortchen hides from her brother and father generating a dramatic panic and search for her which includes waking the neighbors to join the search. The unstable raised fourth scale degree in the opening measures signals her intense frustration and symbolizes her writhing irritation at how tired she is of changing herself for the men in her life. It is almost taunting in its repetition, as she moves into a swirling phrase that also expresses elevating frustration as she wishes only for men’s gratitude. A shift into the relative D minor exposes how worn down she is by the constant need to please men. After the climactic embellishment when she consoles her own heart, the piece moves into a repeated and resolute statement with parallel thirds in the piano part. She declares that she will no longer follow men, but her own head instead! Schwanenlied, from Sechs Lieder, Opus 1 (1846) by Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, text by Heinrich Heine (17971856) Frühling, from Sechs Lieder, Opus 7 (1846), text by Joseph Freiherr Eichendorff (1788-1857) With only about 40 of her 400 works published in her lifetime, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel was a classic example of an extremely talented composer and musician stifled by her gender, religion, social class, and family tradition. Fanny and Felix, her younger brother by almost four years, both received the same musical education as children. They studied piano with their mother, briefly with Marie Bigot, and finally with Ludwig Berger and composition and theory with Carl Friedrich Zelter. When they reached their teenage years, their paths split dramatically. When she was fifteen, Fanny’s father wrote her: “Music will perhaps become [Felix’s] profession while for you it can and must always be only an ornament, never the root of your being and doing…” Seven years later, reminding her of her place, he wrote her again: “You must prepare yourself more seriously and diligently for your real calling, the only calling for a young woman—to be a housewife.” Unlike many of her fellow female composers, particularly her friend Clara Schumann, she did not suffer from lack of self-confidence. On the contrary, she knew she was quite talented and wished that she could make enough money to support herself and her encouraging husband so that he could focus on his own painting. Her father and brother strongly frowned upon her publishing her work, the main reason being that a woman of her high class was not supposed to have an income. She was in perpetual conflict: her desire to preserve her brother’s adoration and her own gender ideology of being a privileged woman expected to tend to her family and be relatively unseen and unheard were at odds with her natural creativity and talent. The song cycle of six lieder from which Schwanenlied comes was the first music she published, but it was done so under her brother’s name to preserve her modesty. Despite Felix’s complex influence, they had a very strong relationship of mutual understanding, inspiration, and trust. They had a mutually giving relationship; she often asked for his advice and valued his opinion and he asked the same of her. They gave one another constructive criticism of their compositions and discussed the ways in which they could improve. Schwanenlied resembles a lullaby, with its melody rocking back and forth with frequent octave leaps and descending thirds. Like most of Fanny’s settings, this piece has two strophes with a slight change in the repetition. This change is an elongation of the word grab (grave), as the swan dives into the depths of the dark water as if it were a grave. Here the subject of the text returns once again to the star of love that fell from the sky (from the first verse) and it is implied that the swan never returned. The natural subjects of the piece representing love and death are common in most Romantic lieder from the 19th century. Frühling is a piece celebrating the coming of spring, making use of the senses: smelling the scents of spring, hearing migratory birds, seeing the blossoming flowers, and feeling the breeze. The quick sixteenth note pattern in the accompaniment seems to sparkle and dance, eager to express the jovial energy brought about by spring. Mendelssohn Hensel makes use of text painting in various moments of her pieces. On the text und die Nachtigallen schlagen (and the nightingales sing), the melody soars above the staff to imitate the nightingales’ vocal outpouring. Sérénade Printanière (1883) by Augusta Holmès Very much inspired by Richard Wagner and greatly supported by her godfather, Augusta Holmès wrote most of her texts herself and composed in secret. She had to hide from her mother who strongly opposed her musical pursuits and was not free to study music until after her mother’s death when Holmès was thirteen. Born in Paris and raised in Versailles by an Irish father and English mother, her music was often considered “an exception to the rule” – the rule that women could not possibly compose. Sérénade Printanière is another song for spring. It focuses not on the freshness of spring’s natural bounty, but is a narrative of a courting couple. The gently rolling, syncopated accompaniment is consistent through the whole piece, even as the vocal line transitions through many moods: adoration, existential questioning, love for life, personal connection, and finally the narration of a passionate kiss. The key change from D major to C major presents a heightened desire to end the confusion in their hearts by uniting them. It returns to D major to finish the piece in an expressive shedding of inhibitions to succumb to the fiery fever in the lovers’ eyes. Les Filles de Cadix (1887) by Pauline Viardot García, text by Alfred de Musset (1810-1857) Born in Paris to a famous Spanish family of musicians, Pauline Viardot García began her musical career with a piano concert debut as a talented fifteen year-old and two years later her operatic debut as Desdemona in Gioachino Rossini’s Otello. Members of the García family often starred in Rossini’s operas, as the father Manuel García was a famous tenor and voice teacher and her older sister Maria Malibran was a famous mezzo-soprano. Pauline also starred in many operas by Mozart before retiring from the stage in 1863, when she began to paint, write plays and compose operettas and songs. Robert Schumann was moved to tears at one of her performances. She also hosted salons in her home in Paris, to which high-profile musicians of the time were invited: Camille Saint-Saëns, Clara Schumann, Franz Liszt, Berlioz, and Alfred de Musset. Les filles de Cadix is a strophic song in French with heavy Spanish influences. The tempo, major key, trills, and triplets contribute to the playful and excited emotion of this song, depicting the three coy girls of Cadiz, Spain flirting and dancing a boléro with three boys in the first verse. In the second verse, a man who wants to seduce them offers the girls gold and they quickly turn him down. The key change in the middle of each verse (from F major to A major) denotes the dialogue in which the two parties engage. Visa en vårmorgon and En vacker höstdag by Elfrida Andrée (1881) One of Sweden’s first female organists and telegraphists, Elfrida Andrée was an important activist in the Swedish women’s movement. Born on Sweden’s largest island, Gotland, Andrée and her sister Fredrika Stenhammar (who became a famous opera singer) were musically trained by their father. Elfrida graduated from Stockholm’s Kungliga Musikaliska Akademien in 1857 as Sweden’s first female organist. She later studied composition in Copenhagen, Denmark. She was appointed the organist in Gothenburg Cathedral in 1867, leading to a position at the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. She composed over one hundred works in the style of contemporary Scandinavians influenced by the Leipzig School (Felix Mendelssohn, Robert Schumann, and Johannes Brahms). She wrote a number of organ symphonies, an opera based on the libretto by Selma Lagerlöf titled Fritiofs saga, several works for orchestra, many for piano trios, quartets and quintets, a number of violin and piano sonatas, and two Swedish masses. I found a recording of Andrée’s songs by Swedish-Egyptian singer Hélène Lindqvist and German pianist Philipp Vogler on their Art Song Project blog. The only known copy of this sheet music was in a library in Stockholm, Sweden. How exciting it was to receive this music through library networking! Both of these pieces are celebratory pieces of two seasons: fall and spring. Visa en vårmorgon is the third and final song in Andrée’s Opus 8. It is a jovial and springy song with rhythmic grace notes to signify a playfulness and delight in what spring brings. The text’s mention of a lone bird, set to the lowered sixth scale degree, adds uncertainty, suggesting the unpredictability of spring. This is then resolved on the high, extended tonic and the piece finishes back in its original key. The first song in the cycle, En vacker höstdag is a lush ode to fall. Andrée crafts leaping phrases, making frequent use of major sixths and melodies that stretch up or skip down, suggesting the falling leaves of autumn and movement on currents of air. The indulgent phrasing suggests a peaceful and humble appreciation of the life still in fall that is soon to fade in the coming winter. The jump of a perfect fifth on the word “himmel” (sky) and use of steady quarter notes is a reference to church psalms, which often make use of this stable interval, as well as textpainting the height and grandeur of the heavens above. Und ob die Wolke sie verhülle from Der Freischütz (1821) by Carl Maria von Weber, libretto by Friedrich Kind (1768-1843) Carl Maria von Weber grew up in a small town in Germany with a father who held many musical directorship positions and a professional singer as a mother. At the age of fourteen Weber wrote his first opera, which was performed at a theater in Freiberg where the family was residing at the time. Later it was performed in Vienna, Prague and St. Petersburg. Der Freischütz was premiered in Berlin on June 21, 1821 and eventually was performed all through Europe to great acclaim. Much of the music was based on German folk songs and it was considered one of the first German nationalist operas. This opera was very popular in Berlin because of its use of folk melodies and became a symbol of resistance to the Franco-Italian style pushed by the king’s unpopular protégé, Spontini. Weber was known as one of the leading German opera composers for many reasons, including that his operas moved beyond the limitations of the singspiel. Like many French operas, Der Freischütz was based on existing literature, Johann August Apel and Friedrich Laun's Gespensterbuch, and Weber made use of a choir. At the age of 39, Weber died of tuberculosis and was buried in London. Richard Wagner performed the eulogy at his reburial in Vienna 18 years after his death. “Und ob die Wolke si verhülle” is Agathe’s cavatina (a short aria without a recapitulation of the first section), in which she reaffirms her faith in God. She had just awoken from a dream in which she was a white dove and her fiancé, Max, fired a gun and hit her. She fell and before she hit the ground she was transformed into her human form but a bleeding blackbird lay at her feet. The frequent leaping ascending vocal lines seem to reach for the heavens and sustain, then fall back down to earth. In the B section, Agathe suggests her acceptance to the possibility of death and finds solace in being in God’s hands. This is portrayed by a brief shift into E-flat minor and denser harmonies that darken the tone. Calvin Lesko, a fellow music student majoring in Composition, has arranged this piece for piano, bass clarinet and flute. This ensemble was made possible with the guidance of Stephanie O’Keefe. Una donna a quindici anni from Così fan tutte (1790) by W.A. Mozart, libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte (1749-1838) Despina, the character who sings this sassy aria, is the maid of the young sisters Fiordiligi and Dorabella, who are put to the test by their fiancés. Set in 18th-century Vienna, the two men pretend to be sent off to war and then, in disguise, they try to seduce the other sister to prove that all women are “like that:” fickle, easily won over, and attention-seeking. They have made a bet with a cynical old bachelor, Don Alfonso, that all women are alike, as stated in the literal translation of the opera title: “Thus do all [women].” There is money in it for Despina, who is bribed by Don Alfonso to convince the sisters to live a little, learn to lie without blushing, cry on command, and flirt to get what they want. There is an expansive gender/feminist discourse surrounding this opera concerning the generalization of women as characteristically fickle, readily conquered, gullible, and easily manipulated for male attention. Some argue that the message of this opera (that all women are “like that”) is Mozart’s criticism of the gendered generalizations we are all faced with, as men also experience gendered stereotypes. However, it is the comedic gendering of these traits that is found problematic: that it was not because of any problems in the relationships or their characters that lead them to cheat, but the mere fact that they are women. Women are also set up against each other, with Despina not pausing to question the ethics of leading the sisters astray for money and male approval by versing them in how a fifteen year-old girl should be, which is the point of her aria, “Una donna a quindici anni.” Despina’s convincing aria makes use of syncopation, embellishments and chromatic patterns to show flirtatiously where she believes a woman’s power lies – in manipulating others (especially men) to follow her wishes. The grand, sweeping phrases at the coda with elevated and extended rhyming vowels (i.e. alto, soglio, posso, voglio) demand authority and obeisance as she claims her dominant status. Finishing with a sweeping repetition on “Long live Despina, who knows how to serve you!” she balances the advice she is giving her employers with acknowledging her subservient position by reminding them that she is their servant. She tells them how to demand attention as if she knows quite well how to achieve it, but distances herself by maintaining her position of servitude and opening a space for them to fulfill her idea of a fifteen year-old girl. Se spiegar (ca. 1820) by Maria Szymanowska Most famous for her piano playing, Maria Szymanowska was said to have made the piano speak and sing. She was born in Poland, toured throughout Europe, and eventually settled in St. Petersburg. There she hosted salons, which were attended by the Polish and Russian aristocracy and artists, such as M. Glinka, S. Pushkin, and A. Mickiewicz. Her compositions were often described as “pre-romantic,” leaning more towards classical style, as one can hear in the simplicity of form and texture in both the accompaniment as well as the vocal parts. Most of her vocal compositions could be classified as romantic, which is a precursor to the lied and a broad term classifying songs in strophic or modified strophic form. In Poland and Russia, she is said to have been an important forerunner of Chopin, especially in her use of Polish folk music and the forms of concert etude, mazurka and nocturne. “Se spiegar” was never meant for public performance, only to be sung in the salons of the aristocracy. This style of song was the beginning of solo art song in Polish music. It is the last of a six-song cycle, titled Six Romances, written in the style of Cherubini. Each of the songs of this cycle is characterized by few ornaments, conventional cadences, and material that varies as it repeats. Verlaine (1954) by Alicia Terzian Why are there no female Bachs? According to Alicia Terzian, it is because history was written and acted out by men in Western Europe. South American composers have long been left outside discussions of music of the Western tradition. This is changing, as Argentina has been considered the leading South American proponent of Western music education and piano pedagogy since the turn of the 20th century. This tradition has included women and nurtured Alicia Terzian into an award-winning composer and musical leader of Argentina. Born in Córdoba, Argentina in 1934, she identifies as a composer, orchestra conductor and musicologist of Armenian descent. In 1954, she graduated with a degree in piano and four years later in composition from the National Conservatory of Music and Performing Arts of Buenos Aires. Terzian is a strong supporter of composers from her home country and travels the world with Grupo Encuentros, which includes violin, cello, flute, clarinet & piano works with their regular singer Marta Blanco (mezzo-soprano) and guest players. She founded the Fundación Encuentros Internacionales de Música Contemporánea festival in 1968, is the Vice President of the International Women's Council of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), is the Vice-President of the Argentine Composers Association, the general secretary of the Argentine Society for Musicology, and the founder of the Latin-American Music Council. “Verlaine” is the third song in a series of three works titled Tres Retratos (Three Portraits) named after Claude Debussy, Juan Ramón Jiménez and finally Paul Verlaine. Verlaine (1844-1896) was a French poet whose texts were frequently set as melodies (French art songs) by French composers. This piece swings between 6/8 time (duple meter) and 3/4 time (triple meter), sometimes switching off from measure to measure. Although both time signatures are subdivided into six submetrical pulses, the two time signatures create subtle yet important changes in interpretation and mood of the piece. The relatively simple piano and vocal part is made complicated by the harmonies, changing time signatures and the dynamics, signaling an intimacy that comes in passionate waves. Canción de cuna para mi corazón solitario from Cánticos para soñar (1993) by Irma Urteaga, poetry by Ofelia Sussel-Marie Irma Urteaga studied choral and orchestral conducting and piano at the National Conservatory of Buenos Aires and the Instituto del Teatro Colón. She later taught at both institutions. She studied composition at the Conservatorio Nacional de Música “Carlos López Buchardo,” where she studied briefly under Alicia Terzian. Between 1974-78 she was the director of the opera studio and house répétiteur (or vocal coach) of the Teatro Colón. She worked for the Ecuador Opera for the following two seasons. Urteaga has held positions in the Association of Argentine Composers Secretary, Second Vice President, then First Vice President. She is an active member of the United Composers of Argentina (CUDA). She also served as Vice President of the Argentine Forum of Composers (FADEC). She has composed mainly vocal works in a neo-romantic style, speckled with contemporary techniques such as atonality and fluid phrasing that freely suit her expressive needs. Her compositional style has changed significantly over the years, from vanguard-influenced atonality to more tonal and legato Post-Romanticism. “Canción de cuna para mi corazón solitario” is the first movement of a song cycle called Cánticos para soñar. A lullaby to the singer’s own heart, it has a haunting quality about it, leaving the listener to wonder what happened to cause her to require such consolation. The arpeggiations that begin the piece suggest a child’s mechanical music box, sounding almost wrong and unsettling due to the half-step dissonances in the chords on the second beat of each measure. The constantly changing time signatures also create an unsettled feeling that permeates the piece. The lowered second scale degree in the second phrase puts the piece briefly into Phrygian mode, which changes the mood dramatically when it is later raised. The extended note that finishes the verse and rises in pitch each time it is repeated represents a heightened emotion, suggesting anxiety or grief. It is soothed by the end to finish the piece in the peaceful and resolved parallel major key, with lyrics showing faith in the heavens to cure the singer’s broken heart. La Rosa y El Sauce (1942) by Carlos Guastavino, text by Francisco Silva (b. 1927) Sometimes called the “Schubert of the Pampas,” Argentinean composer Carlos Guastavino was heavily influenced by 19th century Romanticism. He kept an intentional distance from his contemporaries producing modern and avant-garde music. Guastavino often referenced the gauchesco tradition through his incorporation of Argentinean folkloric tunes, scales, and rhythms that fit naturally with his lush romantic style. Gauchos are an important symbol of Argentina and can be equated with the U.S.’s role of the cowboy – a landless, wandering man of the Argentine plains. Guastavino composed over 500 works, most of them for piano and voice, but published only 162. He toured Latin America, the United Kingdom, Ireland, China and the former Soviet Union. His most productive period came in the 1940s, when most of Latin America was experiencing a strong nationalist sentiment. Many of his pieces feature nature, such as La Rosa y El Sauce, which personifies a weeping willow tree that fell in love with a rose. The winding and melismatic melody seems to portray the branches of the willow tree blowing in the wind, and the waves of emotion that the willow experiences over the “robbing” of the beautiful rose that was by its side. One can easily trace Guastavino’s Romantic influences in his lush harmonies, the natural subjects of the text, and the emotive voice leading that lends itself well to a passionate interpretation. The first half of the piece is in F# minor, but when the “cheeky” young girl enters, he switches to the relative A major to portray the mood of the young girl as she thoughtlessly picks the beloved rose that the willow has seen grow and bloom. On the text “…crying for [the rose],” it goes back to F# minor, to finish the song on long, weeping phrases as the tree cries in its loneliness. Along with clues given in the music, Guastavino’s expressive indications written in the music—“Intense, but contained” and “very delicate”—make his intentions clear. This piece is reminiscent of Schubert’s famous Lied Heidenröslein (1815) and might very well be based on it. Heidenröslein is about a young boy who sees a beautiful rose and breaks it for the sake of hurting the beautiful flower, which is personified and gendered as female. Guastavino changed the story, removing the gendered implications of men intentionally hurting women for the sake of their helpless beauty. Canción al árbol del olvido (1938) by Alberto Ginastera, text by Fernán Silva Valdés (1887-1975) Born to an Italian mother and a Catalan father in Buenos Aires, Alberto Ginastera studied at the National Conservatory in Buenos Aires, graduating in 1938 – the same year that he published Canción al árbol del olvido. He was also an influential teacher and among his students was Astor Piazzolla, who is considered another of the most successful Latin American composers. Ginastera taught at the San Martín National Military Academy from 1941-45 before he was forced to resign by the Peronist regime for signing a petition in support of civil liberties. Like many Argentine musicians and composers during the 20th century, his political stance combined with his status as a public figure made him an easy target during this tumultuous political period, swinging back and forth between democracy and dictatorship. After his forced resignation, he left the country like many other threatened public figures. He studied with Aaron Copland at Tanglewood during a visit to the United States, funded by a Guggenheim fellowship in 1945-47. He returned to Buenos Aires to teach, compose, and build up the Western musical tradition in Argentina, frequently traveling internationally for performances and collaborative projects and organizations. He lived in the United States for a number of years, before moving to Geneva where he resided until his death at age 67. Ginastera wrote Canción al árbol del olvido during the first of his three self-determined stylistic periods, his ‘objective nationalism’ (1934-47), in which he often incorporated Argentinean folk themes and was greatly inspired by the Gauchesco tradition, like Guastavino. His music often alluded to the guitar (an important gaucho instrument), contained folkloric rhythms and scales, and created images of the geography of Argentina and greater Latin America. The rhythms of this piece, like many of Ginastera’s works, are rooted in Argentinean dance traditions. Riner Scivally has transcribed this version of Canción al árbol del olvido for guitar. The original piano part is imitative of the texture of a guitar in the rhythm and suggestion to plucking. Scivally mentioned that transcribing a piece from piano to guitar is like translating a poem into another language, as the guitar and the piano are drastically different instruments. The Cherry-Blossom Wand (1929) by Rebecca Clarke, text by Anna Wickham (1884-1947) Born to a German mother and North American father in England, Rebecca Clarke spent much of her adult life in both United States and England, as she claimed both nationalities. In 1903, she enrolled as one of the few women in the Royal College of Music in London to study violin, but in 1905 she withdrew from the institution when her harmony teacher, Percy Miles, proposed marriage. She returned in 1907 to study composition, a very rare field for women to study, and was the first woman to study composition with Sir Charles Stanford, who convinced her to switch her primary instrument to viola. In 1910 she was forced to give up her studies when her abusive father banished her from the family home after a quarrel. He did not approve of her professional ambitions. She made a career by playing in three all-female chamber music ensembles. When Clarke visited New York, she won second place in Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge’s 1919 competition under a male pseudonym. Mrs. Coolidge wrote, “You should have seen the faces of the jury when it was revealed that the composer was a woman!” Although as she grew older she gained more acclaim for both her professional career playing viola and her compositions, she always struggled with her conflicting love for composing and her doubts of how appropriate it was for her to compose as a woman. Instead of actively pushing up against this idea of the woman’s place, she internalized it as many women do, struggling her whole life with feelings of inadequacy and displacement. She has been quoted as saying, “I always feel that each thing I do is going to be the last thing I’m capable of doing, it always seems sort of a little bit accidental.” She even said that she did not deserve to be the only woman to have “passed through the hands of Stanford,” who also trained the likes of Gustav Holst and Ralph Vaughan Williams. In her later years, she finally began to change her negative self-image, after experiencing great discrepancies in the popularity in her pieces published under either her name or her pseudonym Anthony Trent. Clarke met poet Anna Wickham through their mutual friend, cellist May Mukle. Wickham and Mukle were acknowledged feminists, and Wickham was further determined to expand her freedom of expression when her husband disapproved of the publication of her poems. The Cherry-Blossom Wand was written to be set to music, although Clarke’s is the only known setting. While at first hearing this piece seems romantic and pleasant with the imagery of flowers and nature, it takes on a darker, more cynical tone. Using sweeping melodic phrases, Clarke complicates the idea of an appreciation for fleeting beauty that will not last. In driving away her love with the beautiful cherry-blossom wand, the couple spares one another other the pain of finding out the tragic impermanence of beauty. With great variety in tempi, meter and tonalities speckled with chromaticism, this piece shows some influences of impressionism. Once I thought (Laurie’s Song) from The Tender Land (1954) by Aaron Copland, libretto by Erik Johns (19272001) Inspired by the Depression-era photos of Walker Evans and James Agee’s book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Aaron Copland set The Tender Land in the U.S. Midwest in the 1930s during harvest time. Commissioned by the League of Composers for their 30th anniversary, it was originally intended as an opera for television but was turned down. It was performed first by the New York City Opera in 1954 under the direction of Jerome Robbins and conducting of Thomas Schippers. Born in Brooklyn to parents of Lithuanian Jewish descent, Copland is often referred to as the “Dean of American Composers” for his emphasis on U.S. folk music and geography. His family encouraged him musically; he felt most connected to his sister Laurine because she gave him his first piano lessons and strongly supported him through his musical education and later his career. After graduating from high school, Copland moved to Paris to study at Fontainebleau School of Music with Nadia Boulanger. He was initially reluctant to study with a woman, but since he did not get along with the other male teacher available to him, he agreed to work with her. He strongly valued her sharpness and wide musical knowledge “from Bach to Stravinsky” and her appreciation of dissonances. Although he only planned to spend one year abroad, he spent three years studying with Boulanger. When Copland was commissioned to write The Tender Land, he was skeptical of the opera form, mainly for the common criticisms of unsatisfactory librettists and production values. His fears were warranted: the opera was criticized most for its libretto, and Copland regretted never writing a “grand opera” before his death. The Tender Land, however, is seen today as one of the few U.S. operas in the standard repertoire. Laurie is the first in her family to graduate from high school and is anticipating her need to go out into the “wide world” and explore its meaning on her own terms, not those of her protective family. Sung in Act I, Once I thought is the first clue to conflict and a big change, as it expresses her desire to leave her small hometown and experience what the world has to offer. The recurring motive of the first six measures of the piece is built on B-minor and Cmajor arpeggiations, a duality which does not suggest a stable tonal center. The song travels through many keys and tempo changes, showing Laurie’s excitement and anxiety for what is to come. Copland is known for writing simple chords that vary in intervals and space, and these chords are outlined in the recurring motive. It is used twice more, and the final time is closest to its original form. The final return to the original motive seems to resettle Laurie after singing a chromatic and tonally unstable passage that shows her uncertainty. The chords return to B-minor and Cmajor, as in the beginning; however, the return to reality is short, as the piece finishes in an ethereal and unanswered search for what is to come.