Notes on Imperialism - Lincoln Park High School

advertisement

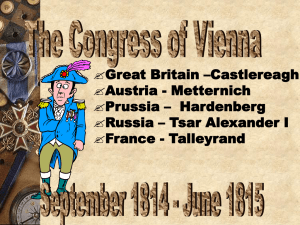

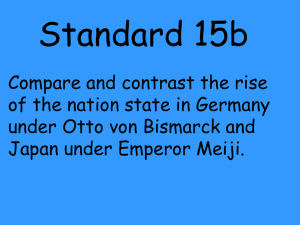

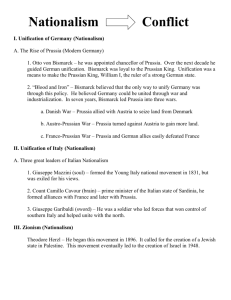

Notes on Imperialism Restructuring Europe After the defeat of Napoleon and the end of the era of French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the major European powers tried to restore peace by strengthening conservative traditional monarchies, which were inconsistent with the revolution ideas that had since been unleashed. The Congress of Vienna The meeting of European powers to settle the peace of Europe from Sept 1814 to June 1815. Participants The Austrian foreign minister, Prince Klemens von Metternich was the architect of the Congress of Vienna. He was generally supported by the other leaders, including Alexander I of Russia, King Frederick William III of Prussia, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand of France, and British foreign secretary Viscount Castlereagh. Metternich was adamantly opposed to revolutionary ideas and had the following goals for the conference: 1. Compensate the victors 2. Restore balance of power to ensure peace 3. Legitimacy (i.e. restoring governments that had ruled before Napoleon and the Revolution) Restoring Europe The Congress made the following changes to European territories in order to restore peace and stability to Europe: Restored French boundaries of 1792 (taking all territories gained in Rev. wars) Added buffer territories to French neighbors including the Netherlands (gained Belgium), Prussia (along the Rhine) German states organized into a loose German Confederation Restored Swiss independence – the country declared itself forever neutral Restored the monarchs of Portugal, Spain, Sardinia, and Kingdom of the Two Sicilies Austria gained territorial control over much of northern Italy (Lombardy, Venetia, Illyria and the Tirol) 1 Compromise The Congress could not agree on the fate of Poland, which Russia aimed to annex for itself. As a compromise, the Duchy of Warsaw was divided between Prussia and Russia. However the other three states (Britain, Austria and France) agreed in a secret alliance to oppose any aggression by either Russia or Prussia. The Concert of Europe The success of the Congress of Vienna was based on compromise and the arrangements by the great powers established to enforce the terms of the congress. In September 1815, Czar Alexander I of Russia called on his fellow monarchs to join him in a holy alliance, pledging to rule as Christian princes, hoping that it would prove to be a vehicle for maintaining international peace. Members were committed to helping each other put down any internal rebellion or revolution. Most states (with the exception of Britain the Papal States and the Ottoman Empire) joined the Holy Alliance Shortly afterwards Britain, Austria, Russia and Prussia, known as the Quadruple Alliance, agreed to meet regularly to maintain peace and discuss common interests The goals of this system became known as the Concert of Europe as designed by none other than Prince Metternich – hoping to combat the spread of revolutionary ideas and maintain peace through European cooperation and a return to enlightened despotism. Unification in Italy and Germany Despite the efforts of the Congress of Vienna, Europe was unable to return to the old order. A growing sense of nationalism and liberalism encourage many Europeans, especially the Italian and German peoples, to see the nation-state as the only way to guarantee individual liberties and national prosperity. The Growth of Italian Nationalism Since Roman times, Italy had been divided into various states with different governments, dialects, economies and customs. Briefly united by Napoleon, nationalist sentiment grew after the Congress of Vienna sought to divide Italy once again, and encourage Austrian control over several states. Early Nationalist Movements 2 Authors used their pen to call Italians to join together and liberate Italy from foreign rule. The nationalist movement became known as the Risorgimento or “resurgence”. In order to promote the cause, many secret societies formed. The Carbonari or “charcoal-burners” plotted to overthrow the Austrians The popular writers Giuseppe Mazzini, once exiled for outspoken nationalism, formed the Young Italy Movement in 1831. Threatened by this movement, Austria declared that members of the movement could be executed if caught. Revolution in Italy Many Italian States hesitated or opposed unification because it would mean giving up their individual power to one central government. In 1848, after Italian nationalists revolted across the peninsula, only Sardinia gained and maintained its independence. Italian Unification Italian nationals were unable to agree on how to achieve national unity – as a federation of states under the pope, a republic, or a constitutional monarchy. Cavour and Sardinia Count Camillo Benso di Cavour, the prime minister of Sardinia, believed that political and economic resurrection were tied. Therefore he promoted economic growth through the funding of railroad construction, industrial encouragement, and by negotiating free-trade agreements. He also strengthened the Sardinian army, dreaming of a kingdom strong enough to drive the Austrians out of Italy. To gain France as an ally against Austria, he transferred the provinces of Savoy and Nice to France in 1860. Garibaldi and the Red Shirts Giuseppe Garibaldi, a member of Mazzini’s Young Italy movement returned from exile in 1859 to lead part of the Sardinian army against Austria. The were able to wrest Lombardy from the Austrians Garibaldi’s followers were known as the Red Shirts because of their red uniforms. They went on to aid Sicily as guerrilla fighters against the Bourbon monarchy, while Cavour conquered central Italy. The Kingdom of Italy 3 The newly conquered and united Italian territories, under the control of King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia agreed to unification in 1861. The only territories that did not join were Venetia (controlled by Austria) and the Papal States (French troops defended the pope). The Italians were able to gain Venetia by siding with Prussia in its 1866 war against Austria, and the Papal States were added when a war between France and Prussia in 1870 forced the French troops to withdraw. Calls for German Unity Nationalism in Germany had been supported by Napoleon who first formed the Confederation of German States. The Congress of Vienna retained the German Confederation, granting Prussia territory that would make it the dominant power in the Confederation. The Zollverein High Tariffs between states impeded the unity of the German economy. So in 1818 the Prussian landed aristocrats (junkers) persuaded the Prussian king to abolish all tariffs by establishing the Zollverein, or customs union. German Liberalism German liberals sought German unity that would promote individual rights and liberal reforms (whether through a republic or constitutional monarchy). Their chance came in 1848, as revolution swept across Europe and Metternich was ousted in Vienna. King Frederick William of Prussia gave into nationalist demands to unite Prussia and Germany, although he continued to assert strong central power. Bismarck and Prussia In 1862, King William I of Prussia, appointed junker and conservative politician Otto von Bismarck as the head of the Prussian cabinet. Bismarck practiced realpolitik or “realistic politics”, pursuing policies based on Prussian interests rather than liberal ideas. He believed it was Prussia’s destiny to lead the German people to unification. When the parliament refused to grant him money for military expeditions he dismissed the assembly and collected taxes anyway. He built up the army into a powerful war machine that could forcibly unite Germany under Prussia. The Unification of Germany 4 Through war and diplomacy, “blood and iron”, Bismarck united the German states into an empire under the king of Prussia. Bismarck’s two main obstacles to growth were Austria’s position of leadership within the German Confederation and influence over the southern German states. During the Seven Weeks War of 1866, Prussia allied itself with Italy in order to provoke a war with Austria. The superior Prussia army was able to defeat the Austrians in only seven weeks, dissolve the German Confederation and annex all but three southern states. The Franco-Prussian war of 1870 allowed Bismarck to persuade the southern German states to join Prussia against the French. The Prussia victory led to the loss of the Alsace-Lorraine territory by France and a huge damages settlement. On January 18, 1871, at the palace of Versailles, the representatives of all the German states proclaimed King William I of Prussia emperor, or Kaiser, of the German Empire. Bismarck was named his chancellor. Motives of Modern Imperialism Imperialism: the policy of extending a nation’s authority by territorial acquisition or by the establishment of economic and political hegemony over other nations. Imperialism (the practice of dominating others through the establishment of great empires) has existed throughout history. During the 1800s, the technological advantages of the Industrial Revolution, as well as the rise of nationalism, allowed the Western world to commit itself to successful territorial expansion that would spread their empires across the globe. The advantages of industrialization (such as science, technology, industry, agriculture, transportation, communication and military) allowed the Western nations to overwhelm peoples who generally outnumbered them. Nationalism allowed states to command the loyalty, service and resources of their inhabitants. Their confidence and cultural arrogance further fostered this expansionist mood. Building New Empires Between 1870 and 1914 the nations of Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the United States engaged in formal empire-building, eventually controlling most of the world with their vast colonial holdings. Some European powers exercised their rule through settlement colonies in which large numbers of Europeans occupied the land (ex: Australia, Algeria, South Africa). 5 Dependent Colonies, on the other hand, were those in which European imperial officials ruled over non-European peoples The Rest of the world war controlled through Spheres of Influence, or territories in which the interest of a single outside nation were dominant. The “new” imperialism The “new” imperialism was not very different from old imperialism, that had been practiced since the late 1400s. Consistent motives included economic, political, strategic, religious and humanitarian. However, imperial expansion was intensified during the 1800s by the rise of nationalism and the spread of the Industrial Revolution. Underlying motives were government concerns for national security and people’s sense of national pride and identity. During this time, after 1870, Europeans spread their control over 10million square miles and 150 million people (a fifth of the world’s land area and a tenth of its population) National Competition and Imperialism Imperialism was spurred by the wave of nationalism that spread through Europe in the 1800s, that had caused the emergence of new German and Italian states (realigning the balance of power in Europe). This caused growing tensions between nation-states that would be played out all over the world. After the loss of French territory in the Franco-Prussian War, Bismarck encouraged France to make up for their losses by expanding their influence in Africa (also thus diverting their attention and desire for revenge in Europe) Modern industrial warfare depended on new technologies such as railroads, repeating rifles and improved artillery. The growth of Industrialization to encourage military growth required access to raw materials and markets. Thus European competition for empires was fueled by the desire to wage modern industrial warfare. Free trade and Empire Each country was interested in developing their own industrial capacity, therefore they shut themselves and their markets off from other countries – a policy known as protectionism. The rise of protectionism and new imperialism represented a return to old mercantilist principles. 6 Technology and Empire During the 1850s, new advances in shipbuilding allowed Europeans to travel safely anywhere in the world. Steamships replaced sailing ships. However the need for coal led to a need for fueling stations – bases where ships could be re-supplied with coal. New medicines allowed Europeans to penetrate areas full of unfamiliar diseases. Humanitarian and Cultural Imperialism Westerners tended to believe that their own civilization (shaped by Christian values and Enlightenment rationalism) was the best in the world – the culmination of human achievement and development. Europeans became concerned with the moral consequences of imperialism. The presence of liberal democracy and human rights at home was inconsistent with the practice of imperialism abroad. Therefore, many adopted the moralist tone of missionaries in describing and advocating imperialism. Imperialism did not lead solely to greater prosperity or good fortune. The overwhelming outcome was competition and hostility among the powers of Europe which would ultimately lead to the Great War. Hanes, et al. World History: Continuity and Change [Holt, Rinehart and Winston: Austin, 1999] pages 536545, 566-678. Craig, Graham, Kagan, Azment, Turner. The Heritage of World Civilizations. Fifth Edition. Combined Volume. [Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2000] pages920-929. 7 Lecture Notes: On Imperialism What is Imperialism: i. the policy of extending a nation’s authority by territorial acquisition or by the establishment of economic and political hegemony over other nations. ii. the practice of dominating others through the establishment of great empires This has existed throughout history. During the 1800s, the technological advantages of the Industrial Revolution, as well as the rise of nationalism, allowed the Western world to commit itself to successful territorial expansion that would spread their empires across the globe. The advantages of industrialization (such as science, technology, industry, agriculture, transportation, communication and military) allowed the Western nations to overwhelm peoples who generally outnumbered them. Nationalism allowed states to command the loyalty, service and resources of their inhabitants. Consider the influence of Nationalism on Europe in the 1800s: After the defeat of Napoleon and the end of the era of French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the major European powers tried to restore peace by strengthening conservative traditional monarchies, which were inconsistent with the revolution ideas that had since been unleashed. The goals of the Congress of Vienna, designed by none other than Prince Metternich hoped to combat the spread of revolutionary ideas and maintain peace through European cooperation and a return to enlightened despotism. 8 Despite the efforts of the Congress of Vienna, Europe was unable to return to the old order. A growing sense of nationalism and liberalism encourage many Europeans, especially the Italian and German peoples, to see the nation-state as the only way to guarantee individual liberties and national prosperity. Case 1: German Unification Nationalism in Germany had been supported by Napoleon who first formed the Confederation of German States. The Congress of Vienna retained the German Confederation, granting Prussia territory that would make it the dominant power in the Confederation. Prussia was not satisfied by being merely a player in the Confederation, but desired complete control of the German state. Which they achieved under Bismarck Bismarck: In 1862, King William I of Prussia, appointed junker and conservative politician Otto von Bismarck as the head of the Prussian cabinet. He believed it was Prussia’s destiny to lead the German people to unification. When the parliament refused to grant him money for military expeditions he dismissed the assembly and collected taxes anyway. He built up the army into a powerful war machine that could forcibly unite Germany under Prussia. Through war and diplomacy, “blood and iron”, Bismarck united the German states into an empire under the king of Prussia. Bismarck’s two main obstacles to growth were Austria’s position of leadership within the German Confederation and influence over the southern German states. During the Seven Weeks War of 1866, Prussia allied itself with Italy in order to provoke a war with Austria. The superior Prussia army was able to defeat the Austrians in only seven weeks, dissolve the German Confederation and annex all but three southern states. The Franco-Prussian war of 1870 allowed Bismarck to persuade the southern German states to join Prussia against the French. The Prussia victory led to the loss of the Alsace-Lorraine territory by France and a huge damages settlement. 9 On January 18, 1871, at the palace of Versailles, the representatives of all the German states proclaimed King William I of Prussia emperor, or Kaiser, of the German Empire. Bismarck was named his chancellor. Case 1: Italian Unification Since Roman times, Italy had been divided into various states with different governments, dialects, economies and customs. Briefly united by Napoleon, nationalist sentiment grew after the Congress of Vienna sought to divide Italy once again, and encourage Austrian control over several states. Mazzini: the heart The popular writers Giuseppe Mazzini, once exiled for outspoken nationalism, formed the Young Italy Movement in 1831. Threatened by this movement, Austria declared that members of the movement could be executed if caught. Cavour: the brain Count Camillo Benso di Cavour, the prime minister of Sardinia, believed that political and economic resurrection were tied. Therefore he promoted economic growth through the funding of railroad construction, industrial encouragement, and by negotiating free-trade agreements. He also strengthened the Sardinian army, dreaming of a kingdom strong enough to drive the Austrians out of Italy. To gain France as an ally against Austria, he transferred the provinces of Savoy and Nice to France in 1860. Garibaldi: the sword Giuseppe Garibaldi, a member of Mazzini’s Young Italy movement returned from exile in 1859 to lead part of the Sardinian army against Austria. The were able to wrest Lombardy from the Austrians Garibaldi’s followers were known as the Red Shirts because of their red uniforms. They went on to aid Sicily as guerrilla fighters against the Bourbon monarchy, while Cavour conquered central Italy. 10 The newly conquered and united Italian territories, under the control of King Victor Emmanuel II of Sardinia agreed to unification in 1861. The only territories that did not join were Venetia (controlled by Austria) and the Papal States (French troops defended the pope). The Italians were able to gain Venetia by siding with Prussia in its 1866 war against Austria, and the Papal States were added when a war between France and Prussia in 1870 forced the French troops to withdraw. The “new” imperialism The “new” imperialism was not very different from old imperialism, that had been practiced since the late 1400s. Consistent motives included economic, political, strategic, religious and humanitarian. However, imperial expansion was intensified during the 1800s by the rise of nationalism and the spread of the Industrial Revolution. Underlying motives were government concerns for national security and people’s sense of national pride and identity. During this time, after 1870, Europeans spread their control over 10million square miles and 150 million people (a fifth of the world’s land area and a tenth of its population) Styles of Imperialism: Some European powers exercised their rule through settlement colonies in which large numbers of Europeans occupied the land (ex: Australia, Algeria, South Africa). Dependent Colonies, on the other hand, were those in which European imperial officials ruled over non-European peoples The Rest of the world war controlled through Spheres of Influence, or territories in which the interest of a single outside nation were dominant. Motives for Imperialsim a. National Competition 11 Imperialism was spurred by the wave of nationalism that spread through Europe in the 1800s, that had caused the emergence of new German and Italian states (re-aligning the balance of power in Europe). This caused growing tensions between nation-states that would be played out all over the world. After the loss of French territory in the Franco-Prussian War, Bismarck encouraged France to make up for their losses by expanding their influence in Africa (also thus diverting their attention and desire for revenge in Europe) Modern industrial warfare depended on new technologies such as railroads, repeating rifles and improved artillery. The growth of Industrialization to encourage military growth required access to raw materials and markets. Thus European competition for empires was fueled by the desire to wage modern industrial warfare. b. Free trade and Empire Each country was interested in developing their own industrial capacity, therefore they shut themselves and their markets off from other countries – a policy known as protectionism. The rise of protectionism and new imperialism represented a return to old mercantilist principles. Technology and Empire During the 1850s, new advances in shipbuilding allowed Europeans to travel safely anywhere in the world. Steamships replaced sailing ships. However the need for coal led to a need for fueling stations – bases where ships could be re-supplied with coal. New medicines allowed Europeans to penetrate areas full of unfamiliar diseases. c. Humanitarian and Cultural Imperialism Westerners tended to believe that their own civilization (shaped by Christian values and Enlightenment rationalism) was the best in the world – the culmination of human achievement and development. 12 Europeans became concerned with the moral consequences of imperialism. The presence of liberal democracy and human rights at home was inconsistent with the practice of imperialism abroad. Therefore, many adopted the moralist tone of missionaries in describing and advocating imperialism. 13