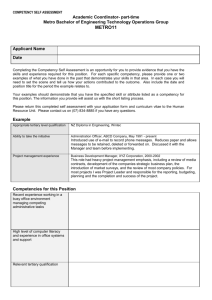

Performance Management 5440KB Nov 11

advertisement

A Description of Performance Management Within a Center Based Program for Children with Autism Presented by: Vincent J. Carbone, Ed.D., BCBA Margaret M. Hagerty, BCABA Emily J. Sweeney-Kerwin, BCABA Carbone Clinic Valley Cottage, NY www.carboneclinic.com NYS Association for Behavior Analysis 17th Annual Conference Verona, NY 1 Introduction • The purpose of this workshop is to provide a description of the application of evidence based procedures to manage staff performance and learner instruction within a center based educational program for children with autism. SETTING • The setting is a clinic for children with autism in Rockland County, NY. • The clinic serves children with autism between the ages of 2 years and 14 years. 2 • The mission of the clinic is to assess learner needs, provide instructional services and then train parents and community based educational providers to implement effective procedures so that the child may transition back to the home school environment. • The methodology is exclusively behavior analytic with an emphasis upon teaching learner cooperation, reducing problem behavior, and teaching language using B.F. Skinner’s analysis of verbal behavior as a conceptual guide. • Ten (10) instructors provide 1-1 instructional services. Most of the instructors are board certified behavior analysts. 3 • About 30 children are served on a weekly basis in the center with no child attending for more than 15 hours per week. • All of the children receive services in other educational settings or their homes during the other instructional hours of the day. • The setting is divided into two classrooms with five instructors and five children in each classroom. • A full time board certified behavior analyst supervisor is assigned to each classroom to manage the instructional environment. 4 Carbone Clinic Organizational Chart Evaluation Services Outreach Services Director Assistant to the Director Office Manager Assistant Supervisor of Education Lead Instructor Instructor Instructor Instructor Instructor Instructor Lead Instructor Instructor Instructor Instructor Instructor Instructor 5 PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT • The center staff have adopted a radical behavioral approach. • As a result, performance of staff behavior is analyzed according to the same principles that are implicated in the control of the learner’s behavior. • Since learner outcomes are directly related to the management of contingencies of reinforcement by the staff in an educational setting, precise management of staff performance may result in the best outcome for learners. 6 • Performance management has been defined by Aubrey and James Daniels (2004) as “ …a technology for creating a workplace that brings out the best in people while generating the highest value for the organization.” • In an educational setting the “highest value” is the learner’s outcomes. • In the past 40 years the principles of behavior analysis have been applied to the management of the behavior of persons within business and industry. 7 • This extension of the principles of behavior analysis to the behavior of persons within organizations has been called Organizational Behavior Management (OBM). • The research published in this area has led us to an understanding of the empirically verified methods and procedures of performance management. • It is this body of literature that we have relied upon to develop a performance management system to improve the quality of instruction within a center based program for children with autism. 8 EMPIRICAL SUPPPORT FOR PROCEDURES • The management of staff performance in settings designed to provide education and treatment to persons with developmental disabilities has been the focus of many research studies in the Organizational Behavior Management literature. (see Babcock, Fleming & Oliver, 1998 and Sturmey, 1998, for a review of these studies) • Reid, Parsons, Green, & Shepis (1991) state “The literature in organizational behavior management (OBM) offers a number of proven procedures for improving the quality of services for persons with developmental disabilities” (p.33) 9 • Organizational Behavior Management has the strongest scientific support for methods that are designed to influence staff performance (Sturmey, 1998). • Moreover, this field of study offers “a wide range of methods for changing staff behaviors” (Sturmey, 1998). • Reid and Parsons (1995) suggest that there are seven steps to effective training and management of the quality of staff performance within a human services delivery system. 10 • Sturmey (1998) refers to these steps as “prototypical OBM” methods. • The seven steps to effective performance management (Reid & Parsons, 1995) are : 1. Specify work skills 2. Provide staff with a checklist description of work skills 3. Describe the work skills 4. Model the work skill behaviors. 5. Observe staff practice the work skills 6. Provide feedback 7. Continue process until staff person is competent. 11 • This is the model of performance management that has been implemented in our center based program. • In addition monthly monetary incentives are provided for exemplary performance as measured by supervisory staff. 12 STEPS OF THE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM The specific steps of our performance management approach include the manipulation of antecedent and consequent variables: 1. Ten (10) days of staff training that explicitly describes the behaviors of instructing children with autism using the methods of applied behavior analysis (ABA). See an outline of the 10 days of training in Appendix A of this document. 13 2. Measurable competency checklists explicitly describing most of the relevant instructional skills to include, Discrete Trial Instruction, Natural Environment Teaching (NET), teaching selfcare skills, etc. 3. Demonstration of the skills 4. Required practice of the skills and measurement of skill competency on the checklists. 5. Unannounced monthly competency checklist skill assessment for the term of employment. 6. Contingency management of staff behavior through verbal feedback immediately following assessment, public posting of performance, monetary incentives for exemplary performance and remedial checks for all skills targeted for improvement. 14 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM • Following training and assignment to several learners, monthly assessments of performance are conducted by a supervisor. • The supervisor watches an instructional session with three to four relevant competency checklists on a clipboard and measures the quality of instruction across a range of instructional settings by recording the occurrence or non-occurrence of the list skills on the checklist. 15 • The competency checklists were developed to measure the accuracy of instructor implementation of various instructional practices and are derived from behavior analytic literature related to the effective treatment of children with autism and other developmental disabilities. • Competencies were developed to measure instructor performance related to: – – – – Natural environment teaching Discrete trial teaching Teaching adaptive living skills Implementation of behavior reduction protocols 16 • The following slides provide examples of competency checklists developed for Intensive Teaching, Natural Environment Teaching, and Teaching Vocal Manding. Copies of these competency checklists are provided in the handouts. 17 • When competency checklist sessions are complete the supervisor provides verbal feedback to the instructor regarding the quality of instruction. • While feedback alone can be effective, its effectiveness can be increased by adding other methods such as programmed consequences for performance (Balcazar, Hopkins, & Suarez, 1985; Alvero, Bucklin & Austin, 2001). • A score of 90 percent on each checklist is required to receive a “passing” score”. 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 • Any areas scored as non-occurrence or of poor quality are listed as targets to be re-checked and remediated within a week. • In addition, on each competency a number of skills have been identified as “critical” to effective instruction. Therefore failure to emit these “critical” responses or incorrect responses are considered “critical errors” and result in a failing score regardless of performance across other skill areas. • When the instructor receives a score of 90 percent or greater on all the competencies scored for that session their name is publicly posted in the staff dinning room indicating their exemplary performance (See Norstrom, Lorenzi, & Hall, 1990, for a review of the research on this topic). 34 • For those who do not meet the 90 percent criterion their names are omitted from the list. • Instructors whose names appear on the list also receive a check for $150.00. • This check is delivered by the instructor’s supervisor at the next Friday morning staff meeting. • Congratulatory applause by the entire staff occurs each time a check is distributed. 35 MONETARY INCENTIVE SYSTEM The monetary incentive system at the center conforms to the OBM research findings (See Bucklin & Dickinson, 2001) that suggests the most effective delivery of money as a consequence includes the following: • Incentives are based only on the employee’s performance. • Incentives are based upon clearly specified behaviors. • Incentives are certain; if the target behaviors occur they will receive the money. • Incentives are paid as soon as possible following the performance rating. 36 • In addition, the monthly performance scores for each instructor is referred to in the employee’s annual review and contributes largely in determining the size of the annual raise and future promotions. • Finally, a similar competency checklist system is used monthly to evaluate each child’s program/data book for accuracy. These competencies are referred to as book audits. • An additional $150.00 amount is awarded for exemplary performance across this measure. • A copy of the book audit checklist is provided in the supplementary packet. 37 Case Study • As an illustration of our system of performance management, a case study of one instructor’s performance on competency checklists during her initial 10 day training and on all subsequent monthly competencies through September 2007 will be presented. • Kristin has Masters in Education Degree from The Pennsylvania State University. She has completed all the coursework necessary for the national board certification in behavior analysis and is currently completing the supervision requirements. 38 • Prior to her employment at the at our clinic, Kristin worked in the field of applied behavior analysis for a number of years but decided to apply for and accept a position at the clinic specifically for the purposes of receiving extensive training and supervision. • Kristin began her training at the clinic in June 2007. During her initial 10 day training, a variety of competency checklists were completed by a supervisor across instructional areas for the purposes of training and as a measure of her baseline performance. • Samples of the following completed competency checklists across these areas are presented below. – Effective Teaching Procedures During Intensive Teaching – Natural Environment Teaching – Teaching Vocal Manding 39 • The examples presented below are representative of the range of possible outcomes on the competency checklist including: • Passing score of 90% correct or greater without critical errors. • Failing score of 90% correct or greater with critical error. • Failing score below 90% correct. • One alternative outcome not presented here is a score 100% correct. • In addition, the samples below provide examples of target remediation. 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 • On the Effective Teaching Procedures competency checklist Kristin’s initially scored 91% correct and one critical error was identified. • Based on the competency checklist three skill areas were identified as in need of improvement and specific targets for remediation were developed. • Targets included: – Teacher uses prompts the reliably evoke the response – Varies elements of teaching procedures based on unique teaching situation – Delivers reinforcer immediately (critical error). • Remediation competencies were then conducted approximately one week later. Kristin remediated all previously identified targets and received a score of 100% correct. 47 • On the Natural Environment Teaching competency Kristin’s initial score was 94% correct and no critical errors were identified. • Although she received a passing score, one target was identified, which was varies elements of teaching procedures based on unique teaching situation. • A remediation competency was therefore conducted approximately one week later on which Kristin received a score of 100% correct. 48 • On the Vocal Manding competency Kristin received an initial score of 87% correct. • Based on the competency checklist two skill areas were identified as not occurring or in need of improvement. Specific targets for remediation were therefore developed. • Skills targeted for improvement included: – Stimulus control transfer is done properly – Varies elements of teaching procedures based on unique teaching situation • Remediation competencies were then conducted approximately one week later. All previously identified targets were remediated and Kristin received a score of 100% correct. 49 • Kristin’s competency scores during the 10 day training period and during subsequent monthly competency sessions are presented in the figure below as a demonstration of her performance over time. • Notice for the Effective Teaching Competency two symbols are presented. The open circles indicate that at least one critical error occurred during the competency. The closed circles indicate that there were no critical errors on this competency. 50 ● = % Correct on Effective Teaching Procedures Competency without critical error ○ = % Correct Effective Teaching Competency Procedures Checklist with critical error ▲ = % Correct Manding Competency Checklist without critical error ■ = % Correct Natural Environment Teaching Competency Checklist without critical error 51 Figure 1. The percentage of correct responses on Effective Teaching, Manding, and Natural Environment Teaching Competency Checklists during training and unannounced monthly competency sessions for Kristin. • As shown in Figure 1, during the 10 day training period in June Kristin’s score on the Effective Teaching Procedures competency checklist was 87% correct with one of critical error. Her score on the Natural Environment Teaching competency checklist was 87% correct and her score on the Manding Competency checklist was 80% correct. • In July Kristin’s score on the Effective Teaching Procedures competency improved to 97% correct without any critical errors. Her score on the Natural Environment Teaching also increased slightly to 89% correct and her score on the Manding competency increased to 87% correct. However, since the criterion for passing is a score of 90% correct across all competency checklist conducted she was not eligible for the monthly bonus during this month. 52 • In August she again scored 97% correct on the Effective Teaching Procedures competency but one critical error was identified and her score on the Manding competency checklist decreased slightly to 86% correct. She was again not eligible to receive the monthly bonus. Her score on the Natural Environment Teaching competency checklist did, however, improved to 100% correct and no critical errors were identified. • In the month of September Kristin received a passing score of 97% correct on the Effective Teaching Procedures competency checklist and no critical errors were identified. She also received passing scores of 94% correct on the Natural Environment Teaching checklist and 93% correct on the Manding checklist. Since Kristin received scores greater than 90% across all competency checklist conducted during the month of September she received a $150 bonus for exemplary performance. 53 • A check for that amount was delivered by her supervisor at a Friday morning staff meeting and her name was added to the publicly posted list of all “passing” instructors. • In addition, Kristin received passing scores on book audits conducted during the months of August and September. • During these months she therefore received an additional $150 bonus delivered publicly during a weekly staff meeting. 54 • Although not an experimental investigation, this case study is offered as an example of both the implementation of our performance management system and the effectiveness of this system in improving the instructional practices of staff. • Since its formal introduction in January 2005 similar results as those presented in the case study have been found across a number of new and existing instructors with whom the performance management system has been used. • Since January 2005 competency sessions have been conducted 308 times with a total of over 924 individual competency checklists completed. During that time a total of 308 book audits have also been conducted. • The cumulative number of competency sessions and the cumulative number of book audits conducted from January 2005 to September 2007 are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3 respectively. 55 Competency Checklists Year Figure 2. The cumulative number of competency sessions conducted per year from January 2005 through September 2007. 56 Book Audits Year Figure 3. The cumulative number of book audits per year from January 2005 through September 2007. 57 • During the first year of the performance management systems implementation, 2005, 120 competency checklist sessions and book audits were conducted. • In 2006, 119 competency checklist sessions and book audits were conducted. • As of September in 2007, 69 competency checklist sessions and books audits have been conducted. 58 • Data collected during competency sessions and books audits have also been summarized across all staff to allow for an overall analysis of staff performance. • The percentage of monthly competencies and book audits passed across all staff during the years of 2005, 2006, and through September 2007 are presented in Figure 4, 5, and 6 respectively. 59 2005 Month Figure 4. The percentage of monthly competencies and book audits passed across all instructors during 2005. 60 2006 Month Figure 5. The percentage of monthly competencies and book audits passed across all instructors during 2006. 61 2007 Month Figure 6. The percentage of monthly competencies and book audits passed across all instructors from January 2007 to September 2007. 62 • As shown in the figures, a significant percentage of instructors pass both their competencies and book audits each month. • Analysis of these data in comparison to employment records suggests that months during which the percentages of passing scores are the lowest correspond with the promotion of previous instructors to other positions and the hiring of new staff. • For example during May, June, and July 2005, four new instructors were hired to replace two lead instructors and two additional instructor who were being promoted to other positions within the organization. 63 • During 2006, however, few new instructors were hired which may account for the higher percentages of passing competencies and book audits. The lowest percentage of passing rates during this year was in March. It was during this month that one new staff member was hired which may account for the slight drop in percentage of passing scores. • In 2007 the percentage of competencies passed decreased during the months of June and July. It was during these months three new instructors were again hired to replace previous instructors who had received promotions. • Kristin, from the case study presented above is an example of one of the new instructors hired during this time. 64 • Due to scheduling changes learners are also occasionally assigned to new instructors. Since a number of highly individualized competency checklists have been developed based on the specific needs of some learners, the assignment of new learners to instructors may also account for lower percentages of passing scores during some months. • In addition, it is the goal of the clinic to provide extensive training and supervision to our staff and to adequately prepare them for a career in behavior analysis. To this end the competency checklists are completed diligently by the supervisor to ensure continued improvement by each instructor for the term of their employment. Only exemplary performances are reinforced. 65 • For those instructors who receive passing scores on either or both the monthly competency checklists and book audits, the performance management system provides a sizable increase in pay from their base salaries. • In total instructors have the opportunity to receive up to $300 a month or $3600 a year in bonuses. • As of September 2007 a total of $54,900 has been paid to staff in monthly bonuses since the introduction of the performance management system. • The cumulative dollar amount paid to staff per month for the years 2005, 2006 and through September 2007 are presented in Figures 7, 8, and 9 respectively. 66 2005 Month Figure 7. Cumulative dollar amount paid to staff per month for performance management during 2005. 67 2006 Month Figure 8. Cumulative dollar amount paid to staff per month for performance management during 2006. 68 2007 Month Figure 9. Cumulative dollar amount paid to staff per month for performance management from January 2007 to September 2007. 69 • During 2005 a total of $19,500 was paid to the staff through the performance management system. This total includes all money awarded to instructors based on exemplary performance on competency checklists and book audits. • In 2006 a total of $23,250 was paid to staff through the performance management system. • As of September in 2007 an additional $12,000 has been paid in performance management bonuses. 70 Limitations • Although we have collected some data in support of the effectiveness of our performance management system, without an experimental investigation of its effect this conclusion is tentative. • We take the replication of the results presented in the case study above across a large number of additional instructors as at least minimal evidence of the effectiveness of this program. • In addition the procedures included in our performance management system are supported by a large body of empirical research within the organizational behavior management literature. 71 • An additional limitation is that we do not have outcome data related to changes in learner behavior as a result of improved instructor performance. • To address this limitation we are currently developing a system that will directly determine the relationship between staff performance and learner outcomes. • We have, however, developed a data based decision making system to evaluate learner progress and to ensure that our interventions are producing the desired changes in the behavior of the children we serve. 72 References Alvero, A. M., Bucklin, B. R., & Austin, J. (2001). An objective review of the effectiveness and essential characteristics of performance feedback in organizational settings (1985-1998). Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 21, 3-29. Babcock, R. A., Fleming, R. K., & Oliver, J. R. (1998). OBM and quality improvement systems. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 18(2/3), 33-59. Balcazar, F., Hopkins, B. L., & Suarez, Y. (1985). A critical, objective review of performance feedback. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 7 65-89. Baer, D., Wolf, M., & Risley, T. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavioral analysis. Journal of Applied Behavioral Analysis, 1, 91-97. Baer, D. (1977). Perhaps it would be better not to know every. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10, 167-172. Bucklin, B. R. & Dickinson, A. M. (2001). Individual monetary incentives: A review of different types of arrangements between performance and pay. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 21, 45-137. Daniels, A. C., & Daniels, J. E. (2004). Performance management: Changing behavior that drives organizational effectiveness (Rev. 4th ed.). Atlanta, GA: Aubrey Daniels International, Inc. Fuchs, L.S., Deno, S. L., & Mirkin, P. K. (1982). Effects of frequent curriculm-based measurement and evaluation on student acheivement and knowledge of performance: An experimental study. (Research Report No. 96) November 1982. Lindsley, O.R. (1971). From Skinner to precision teaching: The child knows best. In J.B. Jordan & L.S. Robbins (Eds.), Let’s try doing something else kind of thing. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children. 73 Michael, J. (1974). Statistical inference for individual organism research: Mixed blessing or curse? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 7, 647-653. Nordstrom, R. R., Lorenzi, P., Vance, H. R. (1990). A review of public posting of performance feedback in work settings. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 11, 101.123. Parsonson, B. S. & Baer, D. M. (1992). The visual analysis of data, and current research into the stimuli controlling it. In T. R. Kratochwill & J. R. Levin (Ed.) Single-case research design and analysis: New directions for psychology and education. Hillsdale, N.J. : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Reid, D.H., Parsons, M.B., Green, C.W., & Shepis, M.M. (1991). Evaluation of components of residential treatment by Medicaid ICF-MR survey: A validity assessment. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24, 293-304. Reid, D.H. & Parsons, M.B. (1995). Motivating Human Services Staff. Supervisory Strategies for Maximizing Work Effort and Work Enjoyment. Morganton, NC: Habilitiative Management Consultants, Inc. Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms. New York: Appleton-Century. Skinner, B.F. (1953). Science and human behavior: New York: Macmillan. Sturmey, P. (1998). History and contribution of organizational behavior management to services for persons with developmental disabilities. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 18(2/3), 7-32. White, O. R. (1986). Precision teaching – Precision learning. Exceptional Children, 52, 522-534. Yssledyke, J. E., Thurlow, M. L., Graden, J. L., Wesson, C., Deno, S. L., & Algozzine, B. (1982). Generalizations from five years of research on assessment and decision making. Research Report No. 100) November 1982. 74 Teaching Independence & Life Skills • Effective educational programs prepare young adults for life after school by teaching independence and life skills. • Applied Behavior Analysis research literature is replete with demonstrations of effective methods to teach life skills. • A repertoire of life skills prepares an individual for a life of independence and a happy and productive life. Life Skills include: 1. Working independently on a task for a substantial period of time 2. Washing hands, brushing teeth, eating independently. toileting, dressing, etc. 3. Following schedules of work, leisure or self-care activities without prompting • On the following page is a description of how these important skills are taught using task analysis and S-R chaining. 75