medieval bestiary2

advertisement

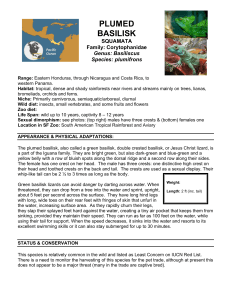

Here begins the book of the nature of beasts. Of lions and panthers and tigers, wolves and foxes, dogs and apes. ~ Aberdeen Bestiary Bestiary is a type of medieval book that was widely popular, particularly from the 12th to 14th cent. The bestiary presumed to describe the animals of the world and to show what human traits they severally exemplify. The bestiaries are the source of a bewildering array of fabulous beasts and of many misconceptions of real ones. They were the artist's guide to animal symbolism in religious building, painting, and sculpture. Unicorn, Dragon, Griffin, Hydra, & Chimaera Basilisk The mythical king of the serpents. The basilisk, or cockatrice, is a creature that is born from a spherical, yolkless egg, laid during the days of Sirius (the Dog Star) by a seven-year-old rooster and hatched by a toad. The basilisk could have originated from the horned adder or hooded cobra from India. Pliny the Elder described it simply as a snake with a golden crown. By the Middle Ages, it had become a snake with the head of a cock, and sometimes with the head a human. In art, the basilisk symbolized the devil and the antichrist. To the Protestants, it was a symbol of the papacy. According to legend, there are two species of the creature. The first kind burns everything it approaches, and the second kind can kill every living thing with a mere glance. Both species are so dreadful that their breath wilts vegetation and shatters stones. It was even believed that if a man on horseback should try to kill it with a spear, the power of the poison conducted through the weapon would not only kill the rider, but the horse as well. The only way to kill a basilisk is by holding a mirror in front of its eyes, while avoiding to look directly at it. The moment the creature sees its own reflection, it will die of fright. However, even the basilisk has natural enemies. The weasel is immune to its glance and if it gets bitten it withdraws from the fight to eat some rue, the only plant that does not wither, and returns with renewed strength. A more dangerous enemy is the cock for should the basilisk hear it crow, it would die instantly. The carcass of a basilisk was often hung in houses to keep spiders away. It was also used in the temples of Apollo and Diana, where no swallow ever dared to enter. In heraldry the basilisk is represented as an animal with the head, torso and legs of a cock, the tongue of a snake and the wings of a bat. The snake-like rump ends in an arrowpoint. Hydra The Hydra had the body of a serpent and many heads (the number of heads deviates from five up to one hundred there are many versions but generally nine is accepted as standard), of which one could never be harmed by any weapon, and if any of the other heads were severed another would grow in its place (in some versions two would grow). Also the stench from the Hydra's breath was enough to kill man or beast (in other versions it was a deadly venom). When it emerged from the swamp it would attack herds of cattle and local villagers, devouring them with its numerous heads. It totally terrorized the vicinity for many years. Griffin A legendary monster, halfeagle and half lion. The Griffin is a legendary creature with the head, beak and wings of an eagle, the body of a lion and occasionally the tail of a serpent or scorpion. Its origin lies somewhere in the Middle East where it is found in the paintings and sculptures of the ancient Babylonians, Assyrians and Persians. In Greek mythology, they took gold from the stream Arimaspias and, neighbors of the Hyperboreans, they belonged to Zeus. The later Romans used them for decoration and even in Christian times the Griffin motif often appears. Griffins were frequently used as gargoyles on medieval churches and buildings. In more recent times, the Griffin only appears in literature and heraldry. Questions for Teaching• What do you think is happening in this image? What do the expressions on the faces of the men tell you about what is happening? • What can you see on this page that tells you that it is part of a book? • This page is from a book called a bestiary, or book of beasts. It is filled with stories that teach moral lessons through images of real and imaginary beasts. What do you think the moral lesson of this story might be? • Are there any other stories you can think of that were created to teach lessons? (Possibly fables by Aesop, folktales, or parables.) • Compare illustrated books from today to this manuscript that was written over 700 years ago. In what ways are they similar? In what ways are they different?