File - The Oasis: Just For Guides

advertisement

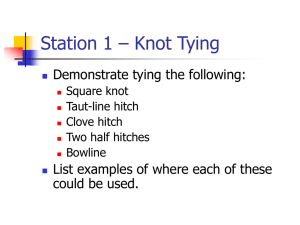

10. Technical Tips 10.1 Clothing and Equipment As experienced, qualified Odyssey guides, all of us have already developed our own packing system that works great for us. We’ve included an equipment list in the handbook to help you answer questions your trippers might have about what to bring, and to serve as a handy checklist when you’re exploding everyone’s packs on Day 0. We’ve also thrown in a few tips that you’ll want to remember both for your own packing and for your tripper letters. Cotton: Cotton soaks up water, takes forever to dry, loses all its insulating abilities, and chafes when wet. We recommend that nearly all of your clothes except t-shirts and possibly some underwear be made of wool or synthetics, which retain warmth even when wet. Of course, in the summer, there will be times when you’ll want to stay cool and wet during the day, so don’t necessarily cut out cotton completely. Make sure to emphasize the problems with cotton in your tripper letters; packing inadequate clothing is a very common beginner mistake in the backcountry. Layers: The best raingear in the world won’t keep you dry if you’re wearing too much stuff underneath it. Getting soaked from sweat can pose just as much of a threat to your warmth, comfort and safety as a driving rainstorm. Wearing several lighter layers that you can put on or take off as necessary will help you regulate your body temperature much more easily than a single bulky jacket. Pack a few warm layers near the top of your pack so you can throw them on quickly when you stop moving. Bring extra clothes: You might not carry them on a personal trip, but as a guide, you’re responsible for the safety of all your trippers, and someone is bound to forget that extra shirt or fall in a lake with their only pair of pants on. Personal clothing list Upper body 1 long underwear top 1 or 2 insulating layers 1 rain shell 1 to 2 cotton t-shirts bathing suit Lower body 1 long underwear bottom 1 lower body shell 1 pr. Shorts underwear bathing suit Head and hands warm hat 1 to 2 bandannas 1 pr. Mittens or gloves 1 baseball hat for sun (optional) Feet 1 to 2 pr. Liner socks, synthetic or wool and thin (optional) 2 to 3 pr. Wool or synthetic hiking socks 1 pr. Hiking boots, 1 pr. Comfortable, lightweight, close-toed camp shoes (no Keens or Crocs, either) Personal gear Frame backpack Sleeping pad Sleeping bag rated to 40-20 F Plastic bags and ziplocks Lighter and matches Small flashlight or headlamp Extra batteries 2 1-quart water bottles (and/or hydration bladders) cup/mug, bowl, spoon pocket knife Hygiene, etc. Chapstick, sunblock, sunglasses Toothbrush and small tube of toothpaste Tampons and pads (even if you don’t think you’ll need them. Being in the woods can affect a woman’s cycle, and someone else will probably need them even if you don’t. Carry used tampons in double ziplock (usually inside an opaque stuff sack) with crushed aspirin added to control the odor Contacts, solution, and glasses Medication (know what your trippers have) Whistle Money for emergencies Optional Journal Camera & film Watch- you might not want people to wear them, but you’ll probably want to carry one for logistical and first aid purposes Insect repellent Mountain Bikers — to the above list, add: bike in good condition bike shoes (in place of hiking boots) bike shorts bike gloves helmet eye protection spare tube and/or patch kit pump repair tools day pack (ability to carry 2 liters of water, lunch, an extra layer, repair tools) Canoers — to the above list, add: baseball hat for sun (required, not optional) sunglasses (required, not optional) 1 pr . Chaco/Teva style sandals or other water shoes (if you use Chacos/Tevas, they can ONLY be used in the canoe. The moment you step outside of the canoe, you MUST put on closed-toed shoes. Sorry, it’s COE policy.) 1 towel Canoers --- from the above list, delete: 1 pr. Hiking boots (only needed if going on a day hike, and then can replace camp shoes) Frame backpack (we use Duluths and dry bags) Finally, when packing your pack, remember what it feels like to carry all that stuff, and try not to carry anything more than necessary. As a guide, you want to be prepared both for yourself and for your trippers, but we all know that you can’t pack enough stuff to be prepared for everything. If you try, you’ll likely spend all your time staggering under your load with your eyes on the ground, and you won’t be able to appreciate your surroundings or pass on that appreciation to your trippers. Also, encouraging your trippers to do without certain comforts may help them in their transition to a new life by allowing them to realize their capacity to adapt to their environment. 10.2 Packs and Pack fitting Trying to get all of your tripper’s packs sized and adjusted correctly can be a real challenge. Its also something you want to deal with before you go into the field- this will save you a ton of headaches and sore shoulders down the road. Here are a few tips to making sure everyone’s pack works for them. Pack fitting: 1. Before you have your trippers try on packs, inspect each one for damage or wear. On external frames, make sure all the ring and pin assemblies are in place and intact, and make sure you have extras in your repair kit. 2. Have your tripper put the pack on and check to see how it matches their torso length. Ideally, the frame stays should extend from the center of the hipbone to 2-4 inches above the shoulders on an internal frame pack. Check the shoulder straps- they should rejoin the pack two or three inches below the top of the shoulders, and should hug the curve of the shoulders closely. Most packs from COE will be external frame, but their shoulder straps should have adjustable attachment points. 3. Put some weight in the pack, and have your tripper put it on with all the straps loose. Tighten the waist belt first, then the shoulder straps, then the load lifters and the sternum strap. Make sure their hips are bearing most of the weight, and check for any pressure spots. Packing the pack: Everyone has their own system for this, and most guides will probably prefer theirs to anything we write in here. But there are still a few important guidelines we’d like to stress which you and your trippers might find helpful. 1. Pack in reverse order of what you are going to need. Put what you are going to need (water, snack, raincoat, compass, trowel, flashlight, etc) towards the top or in an outside pocket, and put the things you won’t need while on trail, such as sleeping bags and extra clothes, on the bottom. 2. Line your pack. You can either get official pack liners or you can just put your sleeping bag and anything else you don’t want getting wet in trash bag liners (don’t forget to buy these at the store when grocery shopping). If you have a pack cover, that works too, but it is always better to be safe than sorry. 3. Heavy gear should be placed close to the back, and relatively high, to direct most of the weight onto the hips on flatter terrain. On steep terrain, heavy gear should be packed lower and closer to the middle of the back to lower your center of gravity. Women naturally have a lower center of gravity than men, so many women may prefer to carry heavy gear near the bottom all the time. 4. Lightweight, bulky clothes should be stuffed into the pack loosely or in stuff sacks instead of being folded or rolled. This fills the space of the pack more efficiently, and keeps things from shifting around. 5. Fuel should always be packed upright, and below your food. You do NOT wanting it spilling all over and ruining your lunch. 6. Food should be on top, right under the things you are going to need, to keep it from getting squashed and to make stopping for lunch much more efficient. Pots are great for packing food in. 7. Packs should be balanced from left to right, with as little hanging off the outside as possible. Anything that is attached externally should be lashed down securely to keep it from swinging around or falling off. A fun way to check and see if your pack is balanced is to set it upright on a flat surface and let go. If it falls one way or another, you know it is too heavy in that direction (although be aware of weight factors such as water bottles that are going to significantly change throughout the day). 8. No one should be carrying more than 25% of his or her body weight. Trippers who aren’t used to carrying a loaded pack should probably be carrying much less. Be sure to explode everyone’s pack on day 0 and prune out anything unnecessary. Guides will probably want to pack lightly themselves in case trippers need help with their loads – although guides should bring a few more extra warm layers in case you have cold trippers. Packing frugally will also leave you enough room for the monstrous amounts of food that most guides seem to end up with after their shopping runs at Tops. Putting on a pack: The easiest way to load a pack without straining your shoulders or back is to lift the pack on to one knee with the straps facing towards you. Slide one arm through the shoulder straps and shift the weight of the pack onto that shoulder. Then slide your other arm in, and bounce the pack into position before buckling and tightening the strap. As an alternate method, find a buddy! Find someone to help you lift the pack, straps towards you, and help you put it on by giving you a little extra stability. It promotes team work and prevents back injuries. Five Straps to Pack Enlightenment: You’ve been fitted to the pack and filled it with stuff, but now you need to adjust. This is important for everyone, regardless of whether or not you own the pack or whether or not you have a ton of experience, to at least start your trip with. One of the greatest sources of discomfort from backpacking is carrying an ill-adjusted pack. This technique, designed by Ben Blakeley, master outfitting wizard, helps to adjust keep the weight on your hips and not your shoulders, prevent pinch points, and provide for optimal comfort. To begin, loosen every strap on the back of the pack. Now, tighten: 1. The shoulder straps. Tighten them down to comfort level – they should be fairly tight but you should still be able to feel your arms. This part, with the loosening and tightening is awkward, so it is best done with a buddy. 2. The hip belt. Tighten to the point when you feel most of the weight on your hips, but can still breath, drink water, and snack. 3. The side tensioners on the hip belt. Although the might not seem like they do much, you can see how much of a difference this can make. 4. The top pulls on the shoulder straps. Pull this to a comfort level, but keep in mind that as you change in terrain, you will want to change the tension in these. When going uphill, you will want to tighten these straps down, in order to keep the weight into your body instead of wanting to pull you back down the hill. When going down hill, you might want them looser, in order to prevent the feeling that you are going to topple down head-first. 5. The chest strap. Although some people may not like to use this at all because they like to breathe deeply, it is a great way to pull some of the weight off the shoulders. How tight you pull this one all comes down to personal preference. This procedure should theoretically be done every time you put the pack on, but it is easy to forget about it. You should do this at least every day, as your pack weight distribution and belly fullness will be always changing. Diagram of ideal weight distributions in an internal frame pack. As noted above, women may prefer to keep weight low and close to the back even on trail due to their low center of gravity. Picture taken from Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills 10.3 Map and Compass for the Outdoor Odyssey Guide By Jerry Carter ‘04 Map and compass skills are essential for any wilderness guide. As an Odyssey guide you need to know and be able to teach at least the following: How to identify what map(s) you need (Could you figure out what USGS map you need if your trip runs off the west side of your map?) How to read and fully understand a USGS topographic map (Do you know how to tell the difference between a stream on a map that is present all-year-around versus one that dries up in August?) How to relate a map to the landscape around you (On the top of a mountain could you roughly orient a map without using your compass?) The proper usage of a compass (Could you shoot a bearing of 34 degrees N?) The meaning and significance of declination (Could you correct for the difference between magnetic north and true north?) How to orient a map (Could you teach your trippers how to orient a map with a compass?) How to measure a bearing on a map (Could you teach your trippers how to take a bearing from point A to point B on a map?) How to take and follow bearing in the field (Could you travel on a straight line bearing through a fog-filled forest with no trail?) If you answered “no” to any of the questions above, you should review the appropriate topics in this chapter of the Odyssey Handbook. In addition it would be helpful to understand the following skills: triangulation intentional offset and following a “handrail” bushwhacking navigation without map and compass Part 1: Some Basic but Important Terms and Concepts If you understand all of these concepts you can skip down to “Part 2: Map and Compass Navigation for Odyssey Guides.” A map is a two-dimensional representation of the three-dimensional world you'll be hiking in. A topographic map uses markings such as contour lines to simulate the three-dimensional topography of the land on a two-dimensional piece of paper. All maps will list their scales in the margin or legend. A scale of 1:250,000 (be it inches, feet, or meters) means that 1 unit on the map is the equivalent of 250,000 units in the real world. So 1 inch measured on the map would be the equivalent of 250,000 inches in the real world. Most USGS maps are either 1:24,000, also known as 7 ½ minute maps, or 1:62,500, known as 15 minute maps (the USGS is no longer issuing 15 minute maps although the maps will remain in print for some time). Standard topographic maps are usually published in 7.5-minute quadrangles. The map location is given by the latitude and longitude of the southeast (lower right) corner of the quadrangle. The date of the map is shown in the column following the map name; a second date indicates the latest revision. Map Size Scale Map to Landscape Metric 7.5 minute 1:24,000 1 inch = 2,000 ft (3/8 mile) 2.64 inches = 1 mile (1 centimeter = 240 meters) 15 minute 1:62,500 1 inch = ~1 mile (1 centimeter = 625 meters) Courtesy Paul Curtis, Outdoor Action Website Bearings: The compass is used primarily to take bearings. A bearing is a horizontal angle measured clockwise from north to some point (either a point on a map or a point in the real world). Compass parts Courtesy Paul Curtis, Outdoor Action Website Map Symbols and Colors: USGS topographic maps use the following symbols and colors to designate different features: Black - man-made features such as roads, buildings, etc. Blue - water, lakes, rivers, streams, etc. Brown - contour lines Green - areas with substantial vegetation (could be forest, scrub, etc.) White - areas with little or no vegetation Red - major highways; boundaries of public land areas Purple - features added to the map since the original survey. These features are based on aerial photographs but have not been checked on land. Courtesy US Geological Survey The map legend contains a number of important details. The figures below display a standard USGS map legend. In addition, a USGS map includes latitude and longitude as well as the names of the adjacent maps (depicted on the top, bottom, left side, right side and the four corners of the map). The major features on the map legend are show and labeled below. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Map Name Year of Production and Revision General Location in State Next Adjacent Quadrangle Map Map Scale Distance Scale Contour Interval Magnetic Declination Latitude and Longitude Courtesy Paul Curtis, Outdoor Action Website Contour lines are a method of depicting the 3-dimensional character of the terrain on a 2-dimensional map. Contour lines drawn on the map represent equal points of height above sea level. Look at the three-dimensional drawing of the mountain below. Imagine that it is an island at low tide. Draw a line all around the island at the low tide level. Three hours later, as the tide has risen, draw another line at the water level and again three hours later. You will have created three contour lines each with a different height above sea level. The three dimensional shape of the mountain is mapped by calculating lines of equal elevation all around the mountain, and then transferring these lines onto the map. On multi-colored maps, contour lines are generally represented in brown. The map legend will indicate the contour interval—the distance in feet (meters, etc.) between each contour line. There will be heavier contour lines every 4th or 5th contour line that are labeled with the height above sea level. The diagram below illustrates how a variety of surface features can be identified from contour lines. 3D View of Mountain showing how contours relate to height Top View of Mountain showing contours Drawn Contour Lines, Courtesy Paul Curtis, Outdoor Action Website Steep slopes - contours are closely spaced Gentle slopes - contours are less closely spaced Valleys - contours form a V-shape pointing up the hill - these V's are always an indication of a drainage path which could also be a stream or river. Ridges - contours form a U-shape pointing down the hill Summits - contours forming circles Depressions - are indicated by circular contour with lines radiating to the center A compass does not point to True North. A compass points to magnetic north. True North: (marked as a star on a topographic map) is where all longitude lines meet. All maps are laid out with true north directly at the top. Unfortunately for our purposes, true north is not at the same point on the earth as the magnetic north pole where your compass points. Magnetic North: The earth's magnetic field is inclined at about 11° from the axis of rotation of the earth, so this means that the earth's magnetic pole doesn't correspond to the Geographic North Pole. The red end of your compass needle is magnetized and wherever you are, the earth's magnetic field causes the needle to rotate until it lies in the same direction as the earth's magnetic field. This is magnetic north (marked as MN on a topographic map). The next figure shows the magnetic lines for the United States (as of 1985). If you locate yourself at any point in the U.S., your compass will orient itself parallel to the lines of magnetic force in that area. Courtesy Paul Curtis, Outdoor Action Website You can see that location makes a great deal of difference in where the compass points. The angular difference between true north and magnetic north is known as the declination and is marked in degrees on your map as difference between N and MN. Depending on where you are, the angle between true north and magnetic north is different. The magnetic field lines of the earth are constantly changing, moving slowly westward (½to 1 degree every five years). This is one reason why it is important to have a recent map. An old map will show a declination that is no longer as accurate, and all your calculations using that declination angle will be less correct. As you will see, understanding this distinction becomes important when navigating with a map and a compass. Fortunately, as long as you always orient your map first before doing any navigation, you won’t have to worry too much about declination. Part 2: Map and Compass Navigation for Odyssey Guides or How to ORIENT YOUR MAP (Odyssey involves a sharing of leadership. Everywhere I use the word “you,” please understand it to mean “you and your co-guide.”) The maps you will probably be using are USGS topographic maps. These can be found for a variety of areas in the Cornell Outdoor Education Library. To supplement these maps you can also look for commercial hiking maps of your area, but because there are all kinds of weird maps out there, I will assume in the rest of this chapter that you are using a USGS topo map. Each USGS map has a name which will be written on it at the bottom and top of the map. To find the corresponding maps look for a name written either on the side or at the corner of the map. If you find the map of that name (with the same scale), then you should be able to fold the white border out of the way and put the maps together. It’s a good idea to have at least two maps of the trail you’ll be traveling on. Another important thing to look at on the map is the date. If your map reads “based on aerial photography from 1955”, there’s probably a lot that is different today. In the Finger Lakes Region, even the most recent maps will probably have new trails and other changes, but of course, you will have scouted your route before the trip. The directions I’m giving assume that you will be using a Silva or similarly designed compass like the ones you’ll get from COE (with the little whistles attached). Look at your map and make sure you can visualize what the entire journey should roughly look like by following the trail in your mind. When does the trail up the hill get steep? How steep and for how long? Do you go through a wooded ravine or big fields? What will be your toughest day? Will you be able to get water at a particular stream or is it intermittent (and won’t be there in August)? * * * Now you’re in the field and you’re group has stopped at a nice lean-to on the side of a pond to camp. You don’t remember there being a lean-to or a pond on this day of your trip so you get kind of worried and you take out the map. You look and see about thirty or so ponds that could all be the one in front of you. However, because you went to the Odyssey Map and Compass seminar, you know exactly what to do. The first thing you should always do when you’re trying to figure out where you are or when you want to get to from point A to point B is ORIENT YOUR MAP. This is the first and most essential thing that people need to learn in my opinion. (You might notice that I stress it a lot by using all capital letters.) Here’s what to do: Orienting a Map 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Make sure your compass has not been adjusted for declination. If you haven’t done this already with a tiny screwdriver, then you shouldn’t worry about it; many compasses aren’t able to even be adjusted for declination. Set your compass to 0 degrees N. (With a Silva compass it should say “0” or “N” under “read bearing here.”) Put your map on a somewhat flat (nonmetal) surface. Then put the side of your compass right next to the MN (magnetic north) arrow on the map. Make sure they line up exactly. Turn the entire map and compass together until “red fred is in the shed.” (The red arrow which points N should be inside the hollow arrow.) Now your map is oriented to reality. In other words, if you drew a line going from your position to the summit of a mountain on the map, you could then theoretically extend the line off the actual map into the real world and you would eventually get to the actual summit. Pretty cool, huh? The map is in line with where things lie in the real world. You look around and see that there is a small hill to the left of the pond and a swamp to the right. You look on your map and find a pond that has a small hill on the left and a swamp on the right. (*Note that using concepts like “left” and “right” will only work if your map is oriented.) Now you find a spot on the map that looks like where you might be. According to the map, there should be a stream about 500 feet in front of you. You stand up look around and bingo! You see the stream. So why is there no lean-to on the map? You look at the date of the topo map, and it says “based on aerial photography from 1965”. This lean-to is probably not that old. Looking at the map again, you realize that you took a wrong turn and are following the wrong trail. Oops! You’ll have to backtrack two miles tomorrow. You better tell your trippers that you goofed. Or maybe you’ll make it seem like you planned this whole situation, and now you’ll let your trippers know that they will have to work together to figure out how to get back on track…. In the middle of your trip, one of your trippers suffers a bad injury. After treating the injury with your excellent WFR or Basic Wilderness First Aid skills, you make a plan to call for help. The quickest way to get help is to bushwhack one mile through a flat sparsely wooded forest to a house on a road where you can make a phone call. Getting from point A to point B: Taking a bearing on the map 1. ORIENT YOUR MAP. 2. Find the point where you are. 3. Find the point that’s your destination. 4. Line the side of your compass with a line going from where you are to your destination. 5. Put “red fred in the shed” But this time, don’t move the map or the compass. Just turn the dial of the compass until the red arrow outline (shed) moves directly over the red N arrow. 6. Now read the bearing under the “read bearing here” mark at the top of your compass. 7. That number is your bearing to get to your destination. Remember it. 8. Put your map away and set your compass to the right bearing. Shooting a bearing in the field 9. Standing, hold the compass at your stomach (not next to your metal belt buckle!) directly in line with your nose. Now lock the position of your compass with your hands and keep your entire body in line with the compass (as if it were part of your body). 10. Looking down at the compass pivot your entire body moving just your feet until (you guessed it) red fred is in the shed. 11. Now look up and find an object directly in your line of sight that is also very distinguishable. (Don’t pick an average hemlock tree in a thick grove of hemlock.) It can be 5 feet away or 500 feet away, as long as you won’t lose it. 12. Now put your compass away for a moment and walk to that point. It doesn’t matter if you travel in a straight line as long as you eventually get to the point you picked. 13. When you get there, start over at step 9 again. 14. Continue this until you get to your destination. If you can’t pick a good point to sight a bearing to, send a friend out to stand as your “target” object. He or she can move right or left until they are directly in your line of sight. In thick forests, this system of “leapfrogging” can work even better than using objects. Using this system, you reach the road and there’s no house there! (This is not uncommon). You don’t know whether to turn right or left. You start going left and then after 100 yards you decide that you’re going the wrong way so you start going right. After half a mile, you start to think that going left was a better idea. So you start heading back, but now you don’t remember where your original starting point on the road was! And it’s starting to rain… Intentional offset Why did this happen? If you were clever, you wouldn’t have tried to shoot a bearing directly to the house. When choosing a destination, it is always better to shoot a bearing to a “safety net” that you can use as a “handrail” to get to your destination. For example, instead of taking a bearing to the house, you should take a bearing to the road south of the house. This means you are purposefully missing your destination so but you will hit the road and then know which way to turn. Another example would be shooting to a stream that you can follow to a lake or camping site. Once you find a “handrail” or (i.e. a stream, trail, road, or other continuous feature) that goes to your destination, you can just follow it. Just make sure you’re following the right stream or trail; that’s a common mistake. The next figure demonstrates how one can return to an original starting point from a mountain summit by bushwhacking down (perhaps a less difficult face) and following a handrail (or “baseline”) back to camp. Courtesy Paul Curtis, Outdoor Action Website Triangulation Triangulation is used to locate your position when two or more prominent landmarks are visible. Even if you are not sure where you are, you can find your approximate position as long as you can identify at least 2 prominent landmarks (mountain, end of a lake, bridge, etc.) both on the land and on your map. This method is most useful when you are somewhere where there are valleys or mountains. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. ORIENT YOUR MAP. Look around and locate prominent landmarks. Find the landmarks on the map (preferably at least 90 degrees apart). Determine the bearing of one of the landmarks (see Bearings page 00). Place the compass on the map so that one side of the base plate points toward the landmark. Keeping the edge of the base plate on the symbol, turn the entire compass on the map until “red fred is in the shed”. Draw a line on the map along the edge of the base plate, intersecting the prominent landmark symbol. Your position is somewhere along this line. 8. Repeat this procedure for the other prominent landmark. The second landmark should be as close to 90 degrees from the first as possible. Your approximate position is where the two lines intersect. 9. You should repeat this process a third time to show an area bounded by three lines. You are located within this triangle. 10. If you are located on a prominent feature marked on the map such as a ridge, stream, or road, only one calculation from a prominent landmark should be necessary. Your position will be approximately where the drawn line intersects this linear feature. Some Useful Tips: Make it a habit of keeping your map and compass handy and refer to them every hour or so to locate your position (more often in low visibility). Make a mental note of the geographical features you will be traveling along and seeing during the day. If you keep the terrain in your mind, you will usually have a general idea of where you are just by looking around. If you are really lost, find the last known position you were on the map. Estimate the distance you’ve traveled since then. Draw a circle around your last known position with the radius being the distance you traveled. You are in that circle somewhere. Make a plan to find out exactly where. Also, ORIENT YOUR MAP. Don’t freak out if you get lost. Getting lost with a full backpack is not a survival situation. Sit down. ORIENT YOUR MAP. Teach a map and compass lesson. Scout your route. Scout your route. Scout your route with your co-guide. Let me repeat that- scout your route. And lastly, ORIENT YOUR MAP. What not to do. I’m not sure why I was chosen to write this chapter, because I’ve spent more time lost than anyone I know. Learn from some of my mistakes. (Yes, these are based on factual events.) Do not: Shoot a bearing to a live animal. Cut through private property with vicious guard dogs. Trust your “primordial navigation senses” over your map and compass. Climb up slopes you can’t climb back down. Get your group lost and angry at you because your motto is, “You can’t be lost if you don’t care where you are.” Rely on a series of broken twigs as a “trail.” Hop over a barricade that reads “Do not enter. Danger.” Cut switchbacks because “real trails go straight up.” Go in circles through a thick field of prickled brambles because “I’m too lazy to look at the map.” Rely on a mountain hermit to save you when you’re lost. Lose your map and compass. Lose the location of your clothes in the middle of a lightning storm. (Don’t ask.) Lose your co-guide. Lose your trippers. It is ok, however, to lose your mind. Just make sure your map is oriented. 10.4 Knots The more knots you know, the more likely you are to know the perfect knot for anything you might like to tie. The following is a selection of knots, with instructions, uses, and tips that are commonly used in ODYSSEY. You don’t need to know every one of the following, but make sure you know at least one knot to tie something off without it sliding (half hitches, friction lock), one knot you can adjust for tension (tautline, truckers hitch), and a knot to tie a loop in your rope (bowline, figure eight follow-through, or butterfly). Knowing more knots will be to your advantage because then you can determine personal preferences. Two Half Hitches Directions: Wrap the rope around an object, then wrap around the tensioned line, with the tail of the rope coming up on the side of your anchoring object. For the second half hitch, wrap your rope tail around the tensioned line again, pulling the rope tail through on the side nearest the first hitch. Uses: This knot makes a loop that tightens down to fix one end of a line that is not under too much tension. Good for doing the first end of a tarp ridgeline, or providing Tips: Don’t use this for lines under extreme tension (like bear bags), because these knots can be very difficult to undo when pulled tight, especially if they get wet. Also, if you really want to make sure the end of your line is secure, you can tie three or four half hitches – any more than that is redundant. Tautline hitch Directions: The tautline is just two half-hitches with an extra twist. When you are making your first wraps around the tensioned line, wrap the line twice before pulling the rope over to make your second hitch. Uses: This is a friction knot like the prussic which adjusts easily, but locks down when weighted. It is an excellent knot to put tension in tarp guylines or ridgelines. Friction Lock Directions: Just wrap the rope around a tree or other object at least five or six times to make a bomber friction knot, then either make a loop in the free end and clip it into the running part of the line as a safety or tie a half hitch or two around the tensioned line. Uses: This is great for tying off bear lines and other lines under tension. Tips: Make sure that you are not damaging whatever tree you are using this on – it is easy to strip the bark off small trees or early in the seasons. Try wrapping at the base of smaller trees – its usually stronger, thicker, and less prone to damage Slipknot Directions: Make a loop in the rope, then fold up one side through the center of this loop to make a second loop. Uses: Good for tying off tent stakes. Tips: Make sure you tie the knot so the line you want to put tension on is not the “slip” side of the slipknot. Trucker’s Hitch Directions: Make a slipknot. Then, take the “slip” end of the rope, feed it around your object, then feed it back up through your loop. Pull on the end of the rope to tension the line, then finish with two half hitches to secure. Uses: Another tensioning knot, although not quite as easily adjustable as the tautline, but still very good for the ridgelines in tarps. Tips: It takes some practice to get the spacing right for where you should tie the slipknot. When you first start using this one, be prepared to have to retie the slipknot a few times. Girth hitch Directions: Fold your rope in half. Holding the bend, wrap the tails of the rope around your object, then feed them through the bend you are holding and pull tight. Uses: for fixing the middle of a line to a cylindrical objecttrees, tent poles, etc. Great for attaching lash straps to an external frame pack. Prussik Directions: You are basically making two girth hitches inside of one another. wrap both ends of the rope twice around the object you are tying to. Uses: This is a friction knot used for ascending ropes. It can be slid up and down easily, but locks when it is weighted Clove hitch Directions: Make two loops in a rope the same way, slide one loop over the other, making sure that the loose ends both come from the center, and then place the centers of both loops around whatever you want to tie to. To tie using the alternate method, make an x around the object you are tying, then pass the free end of the line through the middle of the x lengthwise. Uses: The clove hitch is a simple knot for fixing one end of a line; it is strongest when the direction of pull is parallel to the knot. Good for tarp set-up, tying off the end of a bear line, or making an adjustable personal climbing anchor. Double Fisherman’s Knot Directions: Take the end of one rope, wrap it around your second rope twice – you should see an “X” in this first rope. Now, take the end of the first rope and feed it up under the center of the “X” along the second rope and pull tight. Repeat for the second rope and then pull the two knots together. Uses: The safest way to join two ropes together. Tips: Back it up with overhand knots on either side if used for climbing. Bowline Directions: Make a loop in the rope, feed the tail up through the loop, around the line above the loop, then down through the loop. You can finish with an overhand knot or half hitches if you want, but this knot should hold just fine on its own. Uses: The bowline is one of the best knots for making a fixed loop that won’t pull out. It is perfect for tying your bear bags to the rope in order to hoist them up. Tips: It much easier to tie than its reputation suggests – there are tons of stories which make this knot a fun one to learn. “You have a rabbit hole, and the rabbit come out of his hole, around the tree, and back down the hole.” Bowline on a bight Directions: Fold your rope in half (on a bight). Use the bend as the end of your rope, and then tie the knot the same as you would if you just had one rope. Uses: Good for tying together two bear lines to make a single clip point when using the two-tree method. Figure Eight Follow-Through Directions: Make a loop in the rope, wrap the tail over the longer line and then feed it back through the loop. For the follow-through, run the tail around object, then trace the knot back following every loop exactly. It is difficult to explain it words, so ask a more experienced guide if you have questions on this one. Uses: For tying into a climbing harness. Tips: Make sure to run the knot through the leg loops and the waist loop. Butterfly Uses: This knot allows you to tie a fixed loop into the middle of a rope without using the two ends. Note: Except where otherwise noted, images of knots were taken from Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, published by The Mountaineer 10.5 Tarps Unless you’re on a canoeing trip, you and your trippers will not be carrying tents into the field. All ODYSSEY backpacking trips sleep under tarps if they sleep under anything at all, unless there happens to be a leanto in the area. We’ve come to prefer tarps for several reasons- they’re cheap, lightweight, and easy to pack, and you can cram half your trip under one. They can also be very effective protection from the rain, as long as you set them up properly. This section is dedicated to helping you do just that. Let’s start with the basic rules of tarp setup: tight and low. You want the tarp tight enough to keep it from sagging too much in the rain. If a tarp sags enough to touch you, the water will pass through the tarp onto your previously dry body. Keeping the tarp fairly low will stop rain from blowing in under the edges and increase the amount of dry space you have underneath. Be careful not to overdo it, though: pitch the tarp too low and you won’t be able to get in and out without brushing against it and soaking yourself in the process. Another factor to keep in mind when setting up your tarp is the angle at which you pitch it. Make the angle too flat, and water will start to pool and soak through the fabric instead of draining off. Too steep, and there won’t be any room to sleep underneath. Also, make sure you scan the landscape before picking the best flat spot in the area – it may look awesome, but if it is in a drainage, you might wake up to find yourselves floating away. You’ll have to figure out the compromise that works best for you through experience, trial and error. One of the great things about tarps is their versatility. You can rig domiciles with several tarps that will house the entire group under the same roof. You can adapt a tarp to fit unusually shaped plots. You can mold it into all sorts of shapes of varying aesthetic and functional beauty. That being said, the easiest and most effective way to pitch a tarp is to rig it to look like a traditional Aframe tent with walls on either side. This design is called the pup-tent setup. The main advantages of the pup-tent are that it’s fairly easy to set up and to put tension into, and it creates a large usable space underneath. It is also the setup most of the tarps you will be issued will be designed for. These tarps, which we call NOLS tarps, are cut to create eaves on either side to drain away water that would otherwise blow in from the sides. They also have more grommets and guylines than the average tarp to help you make them tight. The Pup-tent 1. Start by stringing a tight centerline between two trees, or between a tree and a trekking pole or stick. If using two trees, tie off one end with a cinching knot like two half hitches or even a bowline, then tie the other end with a tautline hitch or truckers hitch, and use the knot to put as much tension in the line as possible. If using a trekking pole on one end, tie off the tree first, then tie the trekking pole into the other side of the line with a clove hitch a few feet from the end of the line. Stretch the line out, then angle the pole slightly away from the tarp and stake the free end of the line into the ground. A sturdy waist-high forked stick also works very well. 2. NOLS tarps have two guylines coming off the center line on each side to create the eaves I mentioned earlier. Tie the top one’s off first and tension them before doing anything else. The top two centerlines should be guyed out next. 3. Stake out the corner guylines at 45 degree angles to the body of the tarp. You can use bowlines, slipknots, or trucker’s hitches. If you use tautlines to tie onto the stakes, you’ll be able to adjust the guylines without retying them when the stakes start to pull out, but use whatever you are comfortable with. 4. Next, tie off the side guylines perpendicular to the tarp body. If possible, run the guylines coming from the middle of the tarp outward and upward, so that they pull the walls of the tarp out and keep them from sagging – this also makes for a lot more room under the tarp. This may require some creativity- use trees if you have them, but if no trees are handy, try tying them off with a stick or trekking pole as you would for one end of the tarp in step 1. General tips Count your stakes before you leave. Getting out there and realizing you are three stakes short of an amazing setup is just frustrating. Tie off as many guylines as you can. Use trees, rocks, stakes, or whatever else you can think of that won’t violate LNT rules. More guylines = better tension = drier tarp Be sure to tension the tarp evenly. Tighten one end or diagonal more than another, and you’ll create convenient little channels that will funnel all the rain falling on the tarp, soaking whoever happens to be directly underneath them. Not to mention the facts that tarps are made of thin, lightweight nylon and can rip if you overstretch them or put too much stress on one part. Tie guy lines low on stakes, and put stakes in the ground with their tops angling away from the tarp (aka pointy end towards the tarp) to stop them from pulling out. If you need to tie onto the tarp where there isn’t a grommet, use a ghost: Odysseyap a wad of tarp around a smooth stone and twist once. Tie off your line around the wad, underneath the bulge of the stone. Be careful when you do this, since the stone and the extra tension can wear down the fabric of the tarp. If you can, bring extra cord. You often need just a few more feet to make an awesome tie point. Although the pup-tent is the recommended way to set up these tarps, it is certainly not the only one. It is possible to pitch two tarps together to make a longhouse that can house an entire trip, or erect a lean-to that will shelter you from the rain but still let you enjoy the view from camp. Try different setups and see which ones adapt best to different situations. Be creative… but stay dry. 10.6 Stoves and Stove Repair All of the stoves issued to ODYSSEY guides are MSR whisperlites, in which we burn white gas, a fuel similar to gasoline. Because white gas is a liquid fuel, it has to be both pressurized and vaporized before it can be burned in a controlled, safe manner. These two requirements are the reasons behind most of the complications involved in lighting and using a whisperlite. (A lot of people claim that other white gas stoves like the Peak 1 get around the problems associated with the whisperlite by being better designed and easier to use, but that’s a side issue - whisperlites are what we have, and they work great as long as you know how to use them.) Assembly Use only MSR or SIGG brand fuel bottles with your whisperlite. Fill bottles up to the fill line with fuel, but not beyond- there won’t be enough air space left to pressurize them if you do, and the stove won’t work. Be careful to avoid spilling fuel when filling fuel bottles. If pouring from an MSR fuel bottle, you can minimize spillage using the pour holes in the threads of the bottle cap. Unscrew the cap partway until you see two small holes, one on either side of the threads, and pour through one of them. This should not be a problem you have to deal with during the course of your trip, as the fuel should be provided for you, already in bottles, as part of your group equipment. Screw the pump assembly into the fuel bottle, and pump about 15-20 strokes for a full bottle, or until you feel resistance. You might need to pump as many as 50 strokes. Put the heat reflector around the stove body by sliding it over the fuel line, then unfold the stove legs and snap them into place. Insert the end of the fuel line into the hole in the pump assembly and snap the metal catch arm into place. If you don’t snap in the catch arm, the fuel line could come out during operation, leaking flaming fuel all over the place. This is a bad thing. You can lubricate the fuel line with saliva or pump oil if you need to. When burning white gas, the primer wick is unnecessary. If, for some reason, it is on the stove you are issued, remove it before use. Priming Before you can use your stove, the stove body must be heated so that fuel comes out of the fuel line as a vapor. You accomplish this by burning a small amount of fuel before lighting the stove. This process is called priming. Open the control valve and let a small amount of fuel into the priming cup Close the control valve, then check the whole assembly for leaks. If none are found, light the fuel in the priming cup. Stay kneeling or crouching while lighting the stove, and avoid leaning over it- flames will flare up surprisingly high. Place the windscreen around the stove Wait 1-2 minutes for the flames to die down, then open the control valve again before they go out. You should see a strong, steady blue flame. If the stove goes out, close the valve, wait about 10 seconds, then reopen the valve and light the stove from the top. If flames are yellow or uncontrolled, the stove needs to be primed longer. Turn the control valve off and let the flames die down, then open the valve again as you would during normal priming. Important- if the stove has been off for more than a few seconds, let it cool completely before re-priming and relighting- the ignition of half-vaporized fuel would create a potentially hazardous situation. Use To keep the stove running well, you’ll need to pump 3-5 strokes into the fuel bottle every few minutes to maintain pressure. But be careful not to over pressurize- only pump until you feel firm resistance. Don’t be fooled into thinking that the control valve actually gives you control over the strength of the flame. Whisperlites have two settings- off and flamethrower. Trying to lover the flame too much can result in the flames dying, and the stove simply releasing gas, a dangerous situation. To simmer, run the stove at low fuel pressure, shut off the fuel valve, let the flames almost die out, then reopen the fuel valve until the flames stabilize. Have a pair of pot grips ready to lift your burning food off the stove. Safety As mentioned in Priming, stay on your feet or kneeling when lighting the stove so you can move away quickly if necessary. This is also true when using the stove. Do not sit when using a Whisperlite. You need to be prepared to move away quickly if an accident occurs. Make sure the stove legs and fuel line catch arm are in place, and check for leaks before lighting the fuel in the priming cup. Periodically check o-rings in the pump assembly and the fuel bottle, and don’t use extremely dented or banged up bottles which may leak. Never reach or step over the stove when lighting or priming. If you need something which is on the other side of the stove, stand up and get it, even if it is otherwise within arms reach. Never leave a lit stove, even for a second. Always have someone present whenever the stove is lit to make sure it is working properly Remember: The stove, if used improperly, is the most dangerous thing in the backcountry. Turning the Stove off Close the control valve, and wait for the flames to die out. There is a lag between adjustments to the control valve and their effects on the stove, so this will take a few moments. Do not blow out the flames, as this leaves the rest of the unburned but released white gas in the fuel line. Let the stove cool completely before disassembling. Otherwise you could be releasing volatile white gas vapor into the air. Unscrew the pump assembly away from other people, food, and heat/flame sources, and point it away from your face. Some fuel will spray out when the pressure is released. Fuel bottles can be stored and transported with the pump assembly still inserted- just make sure the control calve is turned off all the way. When storing your stove and fuel, keep them away from your food and cooking gear. White gas and its residues are not good things to ingest. Troubleshooting/repair Be sure to use the heat reflector and windscreen, especially in windy/cold conditions. They have a substantial effect on the efficiency of the stove. Pump maintenance The Whisperlites that COE owns have two different types of pump assemblies, based on when they were purchased. They are both maintained in a similar way. The new model is shown on the left, while the older style is on the right. If you can’t get enough pressure into the fuel bottle, check the pump cup. Remove the plunger from the pump assembly by twisting it counterclockwise, then pull it straight out. Lubricate the pump cup with pump cup oil (in your repair kit), or saliva, then stretch it out by rotating a finger inside of it. If the pump cup is damage or torn, replace it. If the pump won’t hold pressure, clean the check valve assembly. If using the older model pump, turn the check valve counterclockwise, remove the check valve ball and spring, wipe with a cloth, and reassemble. If using the newer model, simply turn the check valve counterclockwise, wipe with a cloth, and reassemble. Burner maintenance The most common reason for problems with burner performance is a clog in the jet, the small valve through which fuel is sprayed into the burner assembly. All of the whisperlites we use are shaker jet models, which means they have a small needle inside the jet designed to poke clogs out of the jet nozzle when the stove is shaken. This will take care of 90% of all burner problems. 5 Steps to Burner Repair- Listed in order of effectiveness and simplicity: 1. 2. Shake the jet- turn the stove off and let it cool, then shake it vigorously upside down or bang it gently on a rock or hard surface. If the jet needle isn’t moving freely, clean the jet. First, try to manually clear the jet nozzle with the jetcleaning wire in your repair kit. If that doesn’t work, unscrew the priming cup from the base of the stove, 3. 4. 5. and pull the generator tube out of the mixer tube. Unscrew the shaker jet with the jet and cable tool, then clean the inside of the jet. If the stove is still clogged, try… Scouring the fuel line. Pull the cable out of the fuel line with the jet and cable tool. Wipe the cable with a cloth dipped in clean stove fuel. Push the cable in and out of the fuel line to scour the generator tube. Repeat scouring and wiping until clean. Reinstall the cable. Flush the fuel line. With the jet and needle out, insert the fuel line into the pump assembly. Pressurize the fuel bottle, and run about ½ cup of fuel through the line into another fuel bottle. Reassemble. The Backpacker’s Field Guide method of reassembly: The fuel line goes into the fixed leg of the stove. Turn the open end of the elbow upside down (so the needle would fall out if it were in). lower the elbow through the leg opening form the top. Now, rotate the Elbow 180 degrees. When the elbow is right side up, slide the top bend of the generator tube into the slot in the flame reflector. Clean the burner assembly. Unscrew the top of the burner with a screwdriver, and clear any carbon deposits on the burner rings or flame reflector. When reassembling, make sure the burner rings alternate between flat and wavy. Most information and all images in this section were derived from The MSR Whisperlite Internationale manual on www.msrcorp.com, with some input from The Backpacker’s Field Manual by Rick Curtiss. O-rings Check your o-rings periodically to prevent fuel leaks. Look for rings that are torn, pitted, or otherwise damaged. Fuel tube o-ring: Leaks at the fuel tube are the result of a torn fuel tube o-ring. To replace, insert a coin into the slot on the fuel tube bushing and twist counterclockwise. Replace the old o-ring, reinsert the bushing, and tighten by twisting clockwise. Control valve o-ring: The control valve o-ring should not be changed unless leaks occur. To do so, turn the control valve counterclockwise and pull gently until it comes completely out of the pump body. The worn o-ring can then be snipped off. To prevent damaging the new o-ring, wrap tape around the needle end of the control valve, then gently move the new o-ring into place. Remove the tape and carefully reinstall the control valve into the pump. Do not over tighten. Fuel bottle o-ring: check for damage and replace if needed. Information from this section was derived largely from www.msrcorp.com, with input from the Backpacker’s Field Manual by Rick Curtiss. 10.7 Water Purification One of the sad facts of life in the outdoors today is that almost no untreated water sources are safe to drink anymore. Even the clearest, coldest stream may be harboring giardia or other micro-organisms that will do nasty things to your digestive tract if given the chance, and most water sources near developed or populated areas are sure to have some level of chemical contamination. In the backcountry, toxic contamination tends to less of an issue, so this section will focus mainly on removing living contaminants- protozoa, bacteria, and viruses that can cause severe dehydration through vomiting and/or diarrhea. There are main ways of dealing with these pathogens: boiling, chemical treatment, and filtration. On a ODYSSEY trip, your first line of defense will be chemical treatment using iodine, but we’ll briefly talk about the other two methods just to give you a sense of your options. Chemical treatment: Two chemicals are commonly used for water purification: iodine and chlorine. Commercially available products like potable aqua (iodine) and halazone (chlorine) are fairly cheap, easy to get, and effective against all kinds of microorganisms, although their effectiveness declines with decreasing water temperature. Things to remember when using chemical purifiers: The effectiveness of all chemical treatment of water is related to the temperature, pH level, and clarity of the water. Cloudy water often requires higher concentrations of chemical to disinfect. Cloudy or turbid water can be strained before purification with a bandanna or cloth. Large chunks may harbor bacteria on the inside that isn’t reached by chemicals during the purification process. Shake your water bottle a bit after adding chemicals to make sure they are evenly distributed. Don’t drink your water for at least 30 minutes after purifying it. If the water is very cold, consider doubling the amount of time you let it stand. About 10 minutes after you add the chemicals, partially unscrew your water bottle cap and tip the bottle until treated water leaks onto the threads of the cap as an extra safety measure. If you don’t like the chemical taste in your water, you can add sugary drink mixes to cover it up, but make sure to wait until after the chemicals have had a chance to work. Iodine will react with the sugars in drink mix, turning your water practically black without purifying it. Iodine Iodine is commercially available both as tablets (potable aqua) and in crystal form (polar pure). Iodine tends to be more popular than chlorine, partly because it seems to work better at killing things like Giardia. However, some people can’t use iodine due to allergies or health problems. People with allergies to shellfish should not use iodine to treat their water. Pregnant women should talk to their doctor before using it. Make sure to look for iodine related issues on your trippers’ medical information forms, and ask if you aren’t sure. Besides needing warm, relatively clear water to work, iodine should also be kept away from light, which is why potable aqua and polar pure bottles are tinted dark. Polar Pure (crystal form): Fill the bottle with water, shake, and cap. Let it sit for about an hour. To purify your water, add as many capfuls of the resulting iodine solution as indicated by the chart on the side of the polar pure bottle. Cap your water bottle and let it sit for the required 30 minutes, and remember to bleed the threads as described above. Remember to refill the polar pure bottle after use. Potable aqua (tablets): This is the form of iodine that you will receive on your ODYSSEY trip. Add 1-2 tablets to a quart of water as indicated on the potable aqua bottle, and let sit for 30 minutes after the tablets have been mostly dissolved. Chlorine Although somewhat less effective than iodine, chlorine does work as a means of water purification, and may be the best option for people with iodine allergies. Your best bet is probably to buy a commercially available product like Aqua Mira and follow the directions. Boiling Boiling water may not be the most convenient way of purifying it, but it is one of the simplest. By the time a pot of water is boiling, everything you wouldn’t want to drink is already dead, but let it boil for at least another minute just in case. This is obviously the best way to purify cooking water, which you’ll probably want to boil anyway. The main drawback to boiling is that it can use up a lot of fuel, which can be a logistical problem, especially for longer trips. It also runs counter to the ODYSSEY ethic. Filters You almost certainly won’t have to deal with filters on a ODYSSEY trip, since they are both heavier and more expensive than iodine. They do, however, remove most of the crud and floaties that chemical treatments can’t, which greatly improves the taste of the water. Also, filtered water is ready to drink instantly, which makes filtration a very convenient method of purification. There are three categories of filtration devices available: Filters (which remove Giardia, and anything else larger than 1-2 microns), Microfilters (which also take out bacteria as small as .2 microns), and purifiers (which eliminate viruses as well). Purifiers are generally rated to .004 microns. The only non-chemical purifiers we are aware of use a ceramic core, which can crack if mishandled. Caution: there are several purifiers on the market which claim to remove viruses with an iodine-impregnated core.