Test review: The Michigan English language assessment battery

advertisement

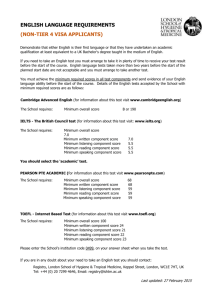

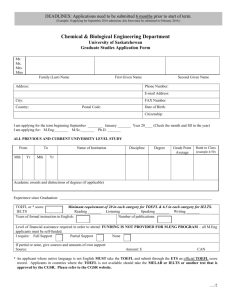

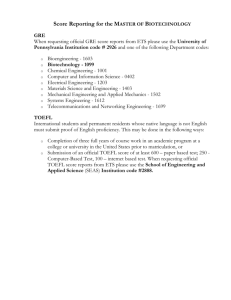

Running Head: TEST REVIEWS Test Reviews Albatool Abalkheel Colorado State University 2 TEST REVIEWS Test Reviews For students, having a certain level of proficiency in English is an essential requirement in most universities that use English as the main language of instruction, including Qassim University in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, many publishers and testing companies publish tests that are used to assess the English language abilities of adult learners. However, the published tests differ from each other in some of their characteristics, such as their costs, and structures. So, it is important to evaluate these tests to identify which ones are appropriate for certain purposes and individuals. The test of English as a Foreign Language – Internet Based Test (TOEFL iBT), International English Language Testing System (IELTS) and Michigan English Language Assessment Battery (MELAB) are all designed for assessing English language abilities and are used to make decisions regarding who is proficient enough in English to be selected for entrance to an educational institution. These three tests are the focus of this paper because they all assess the four language skills (reading, writing, listening and speaking). These four skills are essential in achieving academic success in universities that use English as the language of instruction. This review will compare these three tests because they are common in Saudi Arabia to decide which one is more appropriate for students who want to gain admission as an English major at Qassim University in Saudi Arabia. Several Saudi universities accept the result of each of this test, but Qassim University want to accept the result of just one or two standardized tests. Then, they have to report to the ministry of Higher Education in Saudi Arabia about the tests that they would accept with a report about these tests and why they decide to use them. After the decision, the university holds some workshops for students who will take these tests to help them with strategies that may help them to get high scores. 3 TEST REVIEWS TOEFL iBT Table 1 Description of TOEFL IBT™ Test Publisher Educational Testing Service ETS. ETS Corporate Headquarters, 660 Rosedale Road, Princeton, NJ 08541 USA Tel: 1-609-921-9000 Website: http://www.ets.org/toefl Publication Date Target population 2005 Nonnative-English speaking students who want to study at institutions of higher education that use English as the language of instruction Cost of the test From $160 to $250 (Sawaki, Stricker & Oranje, 2009) Overview As shown in Table 1, the TOEFL iBT was published in 2005 by the Educational Test Service (ETS). It is accepted as proof of English proficiency by more than 9,000 institutions in more than 130 countries, according to the test website. An extended description of the test is provided below (see Table 2). Table 2 Extended Description for TOEFL iBT Test TOEFL iBT can be used to make decisions of who is proficient enough in purpose English to be selected for entrance to an educational institution (www.ets.org). Another purpose of TOEFL iBT is to measure the communicative language ability and language proficiency of people whose first language is not English (Jamieson, Jones, Kirsch, Mosenthal, & Taylor, 2000). The TOEFL iBT score is used for English-language learning program admissions, and certification candidates. Test structure The test has four parts: reading, listening, speaking, and writing. The reading section is designed to measure students’ comprehension based on finding main ideas, inferring, understanding vocabulary in context and understanding factual information. Topics of texts are various, such as hard sciences topics. In the listening section test takers will listen to the conversations and lectures only once and they can take notes while listening. This section is designed to measure test takers’ ability to understand spoken English through recognizing a speaker’s attitude, understanding the organization of given information, and making inferences about what has been said. The speaking section is designed to assess test takers’ ability to express an opinion about a familiar topic and to summaries reading or listening tasks. It deals with a variety of topics, such as topics about campus situations. The writing section is designed to measure test takers’ ability to expressing their opinions about a given topic through writing based on their knowledge and experience on the given topic, and their ability to write a summary of a listening passage and relate it to a reading passage. Test takers type their answers on the computer. 4 TEST REVIEWS The following table shows the tasks in each section: Skill Tasks Questions Reading (60-100 minutes) 3 - 5 passages (about 700 words each) 12 - 14 multiple-choice items each (36 -56 items total) Listening (60 – 90 minutes) 4 - 6 lectures 2 - 3 conversations 6 multiple-choice items each (34 -51 items total) 5 multiple-choice items each Speaking (20 minutes) 6 tasks: 2 independent tasks 4 integrated tasks General questions on familiar topics The first two: an oral and a written stimulus The second two: oral stimulus Writing (50 minutes) 2 tasks: 1 independent task Writing an essay responding to a (20 minutes) general question (150- 225 words) 1 integrated task Writing a summary of a lecture and a (30 minutes) reading (150-225 words) (“TOEFL iBT™ Test Framework and Development,” n.d.; “TOEFL iBT® Test Content,” n.d.). Scoring of the test The total score for this test is 120. Each section is scored on a scale of 0-30. Reading and listening tasks are scored by computer. Each of the six tasks in the speaking part is rated from 0 to 4 by ETS-certified raters, based on four criteria: general, delivery, language use, topic development. The scores then are summed and converted to a scaled score of 0 to 30. The writing tasks are rated from 0 to 5. A human rater assesses the content and meaning in writing tasks, while automated scoring techniques assesses linguistic features. This is the distribution: Skill Scale Level Reading 0 – 30 High (22 - 30) Intermediate (15 - 21) Low (0 -14) Listening 0 – 30 High (22 - 30) Intermediate (15 - 21) Low (0 -14) Speaking 0 – 30 Good (26 - 30) Fair (18 - 25) Limited (10 -17) Weak (0 - 9) Writing 0 – 30 Good (24 - 30) Fair (17 - 23) Limited (1 -16) Total Score 0 – 120 (“TOEFL iBT™ Test Framework and Development,” n.d.; “TOEFL iBT® Test Content,” n.d.). 5 TEST REVIEWS Statistical distribution of scores Standard error of measurement ETS reported the following means and standard deviations of test-takers who took the TOEFL-iBT between January and December of 2013 (Test and Score Data Summary for TOEFL iBT® Tests, 2013). Section Mean SD Reading 20.01 6.7 Listening 19.7 6.7 Speaking 20.1 4.6 Writing 20.6 5.0 Total 81 20 Calculating the Standard error of measurement (SEM) of the total score of the first year’s operational data from 2007 ended up with 5.64. A closer look indicates that reading, listening and writing have a higher SEM than speaking. Score Scale SEM Reading 0-30 3.35 Listening 0-30 3.20 Speaking 0-30 1.62 Writing 0-30 2.76 0-120 Total 5.64 (“Reliability and Comparability of TOEFL iBT™ Scores,” 2011) According to Lawrence (2011), SEM refers to how close a test taker’s score is to the test taker’s true ability score. The larger the standard error, the wider the band score and this indicate that the score is less reliable (Miller et al., 2008). Evidence of The reliability estimation in TOEFL iBT is based on two theories: item response Reliability theory (IRT) and generalizability theory (G-theory). IRT is used with reading and listening parts, while G-theory is used with speaking and writing parts. These two different methods were used because the test has constructed-response and selected-response tasks. G-theory measures the score reliability for tasks in which the test taker generates answers, while IRT is used with tasks in which test takers select from a list of possible responses. A generalizability coefficient (G coefficient) is used as the index score reliability in this framework. TOEFL iBT® has high reliability. The reliability estimates for the four parts are provided in the following: Reliability Score Estimate Reading Listening Speaking Writing Total 0.85 0.85 0.88 0.74 0.94 The reliability estimates for the reading, listening, speaking, and total scores are relatively high, while the reliability of the writing score is lower. (“Reliability and Comparability of TOEFL iBT™ Scores,” 2011) TEST REVIEWS 6 Evidence of The validation process for TOEFL iBT started with “the conceptualization Validity and design of the test” and continues today with an ongoing program of validation research” (“Validity Evidence Supporting the Interpretation and Use of TOEFL iBT Scores,” 2011). Different types of validity evidence have been collected for TOEFL iBT. It is reported on the official website of the test that a strong case for the validity of proposed score interpretation and uses has been constructed and that researchers conducted studies of “factor structure,” “construct representation,” “criterion-related and predictive validity” and “consequential validity.” . According to Lawrence (2008), TOEFL iBT is valid because the task design and scoring rubrics are appropriate for the purposes of the test; it is related to academic language proficiency and the linguistic knowledge, the test structure is related to theoretical views of the relationships among English language skills; (p. 4-10). 7 TEST REVIEWS IELTS Test Table 3 Description of IELTS Publisher University of Cambridge ESOL Examinations, the British Council, and IDP: IELTS Australia. Subject Manager, University of Cambridge ESOL Examinations, 1 Hills Road, Cambridge CB1 2EU United Kingdom; telephone 44-1223-553355; ielts@ucles.org.uk. Website: http://www.ielts.org/ Date of publication 1989 Target population Nonnative-English speaking who want to study or work where the language of communication is English Cost of the $185 to December 31, 2012, $190 from January 1, 2013 test (“IELTS: Test Takers FAQs,” n.d.; “IELTS: The Proven Test with Ongoing Innovation,” n.d.) Overview As shown in Table 3, the publisher of this test is IELTS Australia and British Council, and it is a version of the IELTS test that was used in Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom in the 1980’s (Alderson and North, 1991). It has two modules: the Academic module and the General Training module. An extended description is provided in Table 4. Table 4 Extended Description for IELTS Test Both modules of the IELTS test are used to assess the language ability of adult purpose people. The Academic module is for candidates willing to do their graduate or undergraduate studies and those who want “professional registration” in an English speaking place, while the General Training module is for candidates willing to migrate to or work in an English speaking country or those who want to study at below degree levels in an English speaking place (Choose IELTS, n.d.). Test Structure Both modules have listening, reading, writing and speaking parts. However, they differ in their reading and writing tasks. The listening section allows test takers 30 minutes to listen to “four recorded texts, monologues and conversations by a range of native speakers” and to answers 40 questions based on these recordings. These questions have different kinds and assess different sub-skills. Multiple-choice items assess “detailed understanding of specific points, or general understanding of the main points of the recording” and to measure their following of conversation between two people and their recognition of “how facts in the recording are connected to each other” through matching. Diagram labeling questions are designed to assess test takers ability ”to understand, for example, a description of a place, and how this description relates to the visual” and their 8 TEST REVIEWS “ability to understand explanations of where things are and follow directions.” Sentence completion tasks are designed to assess test takers ability to” understand the important information in a recording.” Short-answer questions are designed to assess test takers ability to “listen for facts, such as places, prices or times, heard in the recording.” Regarding the reading section, both modules have three sections and allow test-takers 60 minutes to read and answer questions. Each section in the Academic module has one text, which “range from the descriptive and factual to the discursive and analytical.” The first section in the General module has two or three short factual texts, the second has two short factual texts, and the third has one longer, more complex text. Test takers are asked to complete a total of 40 different questions. Each question assesses some sub-skills. Multiple-choice tasks are designed to assess test takers’ understanding of main and specific points. Identifying information (True/False/Not given), identifying writer’s views/claims, sentence completion, diagram labeling and short answer question assess test takers ability to recognize specific information given in the text, while matching headings assess test takers ability to scan a text to find specific information. The writing section in the Academic module consists of two tasks that test taker has to complete in 60 minutes. In the first task test-takers are given a graph, table, chart, or diagram for which they should describe, summarize or explain the information in 150 words. This task is designed to assess test takers’ ability to organize, present and compare data and their explanation of a process. The second task is writing an essay responding to a point of view, argument, or problem in 250 words. This task assesses their ability to “present a solution to a problem, present and justify an opinion, compare and contrast evidence, opinions and implications and evaluate and challenge ideas, evidence or an argument.” The writing section in the General module consists also of two tasks that test taker has to complete in 60 minutes. The first task is writing a letter responding to a given situation. The letter either explains the situation or asks for information (150 words). This task is designed to assess test takers ability to “ask for and/or provide general factual information express needs, wants, likes and dislikes express opinions.” The second task is writing a short essay responding to a point of view, argument or problem (250 words). This task has the same skills that are assessed by the second task in the Academic module. The speaking section has three face-to-face oral interview tasks that take 11-14 minutes. The first task involves questions on familiar topics (4-5 minutes). This task assesses test takers ability to “give opinions and information on everyday topics and common experiences or situations by answering a range of questions.” The second task asks test taker to respond to a particular topic based on a task card in 3-4 minutes. This task assesses test takers’ ability to speak at length on a given topic. The last task requires test-takers to respond to further questions that are connected to the topic from the previous task (4-5 minutes). It assesses test takers ability to explain their opinions and to analyze, discuss and speculate about issues.” (“IELTS: Information for Candidates,” n.d.) Scoring of the test The reading and listening sections are assessed by computer, while the writing and speaking sections are rated by IELTS raters who are trained and certified by Cambridge ESOL. Then the scores are averaged and rounded to have a final score shown on a Band Scale ranging from 1 to 9 with a profile score for each of the four part where 9 is the highest score. Each item in the listening and reading parts is 9 TEST REVIEWS worth one point. Scores of each part out of 40 are converted to the IELTS 9-band scale. Writing is assessed based on task achievement, coherence and cohesion, lexical resource, grammatical range and accuracy. Speaking is assessed based on fluency and cohesion, lexical resource, grammatical range and accuracy and pronunciation. (“IELTS: Information for Candidates,” n.d.). Distribution of scores are provided as follow: Skill Listening Statistical distribution of scores Score Range 0 – 40 Raw Score out of 40 16 23 30 35 Band Score 5 6 7 8 Academic Reading 0 – 40 15 23 30 35 5 6 7 8 General Training Reading 0 – 40 15 23 30 34 4 5 6 7 Speaking Writing Not Applicable Not Applicable N/A N/A 0–9 0–9 Total Score Not Applicable 9 The distribution scores and standard error of measurement of listening and reading (2012) is reported. However, it is not reported for writing and speaking in the same manner because they are not item-based and “candidates' writing and speaking performances are rated by trained and standardized examiners according to detailed descriptive criteria and rating scales.” Skill Listening Academic Reading General Training Reading Mean 6.0 5.9 6.1 St Deviation 1.3 1.0 1.2 (IELTS: Test Performance, n.d.) Standard error of measurement Standard error of measurement of Listening and Reading (2012) is reported.in the following way: Skill Listening Academic Reading General Training Reading SEM 0.390 0.316 0.339 This is interpreted as less than half a band score. (IELTS: Test Performance, n.d.) TEST REVIEWS Evidence of reliability Evidence of validity 10 Cronbach's alpha is used to report the reliability of Listening and Reading tests. It is “a reliability estimate which measures the internal consistency of the 40item test.” Average alphas across 16 listening versions, General module reading versions, and Academic reading versions in 2012 are reported. The average alpha was 0.91 for the Listening, 0.92 for General reading module and 0.90 for Academic reading. The Reliability of rating in Writing and Speaking is “assured through the faceto-face training and certification of examiners and all must undergo a retraining and recertification process every two years” and many experimental generalizability studies were carried out to examine the reliability of ratings. Coefficients of 0.83-0.86 for Speaking and 0.81-0.89 for Writing are shown by Gstudies based on examiner certification (“IELTS: Test Performance,” n.d.). Ongoing research that works on ensuring that the test is functioning as intended is reported. Research topics are related to the impact of IELTS on enrolling higher education and professional registration, “prediction of academic language performance, stakeholder attitudes, and “test preparation” (“IELTS: Predictive validity,” n.d.). Predictive validity of IELTS is the focus of many reported studies. Hill, Storch and Brian Lynch (1999) investigated the effectiveness of IELTS as a predictor of academic success of international students (n=66) and found that the relationship between GPA and IELTS scores was strong. Allwright and Banerjee (1997, as cited in Breeze & Miller, 2011) found that there is a positive correlation between the English-medium academic success and overall IELTS band scores of international students. 11 TEST REVIEWS MELAB Table 5 Description of MELAB Publisher English Language Institute, Testing and Certification, MELAB Testing Program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109–1057, USA; phone: +1 734 764 2416/763 3452; email: melabelium@umich.edu; websites: http://www.cambridgemichigan.org/melab Publication date 1985 Target population Adult nonnative speakers of English who want to study or work where the language of communication is English Cost of the test $60 plus $15 for oral interview Overview The English Language Institute at the University of Michigan developed the Michigan English Language Assessment Battery (MELAB). The standardized test for assessing English language proficiency is introduced from one to three times monthly at scheduled dates. Table 6 Extended description for MELAB Test Test MELAB is designed to assess advanced-level English language competence of purpose adult nonnative speakers of English for admission purposes and to judge their fluency in English, and to assess professionals who need English for work, training or employment purposes (“About the MELAB,” n.d.; Weigle, 2000). Test structure The test includes three essential parts: written composition, listening comprehension, and grammar, cloze, vocabulary and reading comprehension (G-CV-R), and one optional part (speaking test). The writing part allows test-takers 30 minutes to write an essay of 200 -300 words. Test takers choose to write on one of two essay topics: opinion, description or explanation of a problem. The listening part allows test takers 30 - 35 minutes to answer multiple-choice question based on “questions, statements or short dialogs, and two to three extended listening texts. Grammar- cloze-vocabulary- reading test (G-C-V-R) allows test takers 80 minutes to answer 100 questions. These questions include 30 - 35 multiple-choice questions based on American conversational grammar where candidates have to choose only grammatically correct answers. They also include 20 - 25 fill in the gaps in two cloze passages by choosing the correct words in terms of grammar and meaning. In addition, they have 30 -35 multiple-choice questions where candidates have to choose the best word or phrase in terms of meaning to complete a sentence. The remaining questions are multiple-choice items where candidates have to choose the correct answer in a set of comprehension questions in 4 - 5 reading comprehension passages (“MELAB Success,” n.d.). The speaking part allows test takers 10 – 15 minutes. In a face-to-face interview, candidates are asked about their backgrounds, future plans, and opinions on certain issues (Johnson, 2005). 12 TEST REVIEWS Scoring of the test All tests are sent to the English Language Institute, University of Michigan for scoring. However, the speaking section is not included because it is scored locally (Weigle, 2000). Listening and GCVR parts are computer-scored where “each correct answer contributes proportionally to the final score for each section and there are no points deducted for wrong answers.” A scaled score is calculated through a “mathematical model based on Item Response Theory” (“MELAB Scoring;” n.d.). For Writing, two trained raters score the essay according to a “ten-step holistic scale.” The scale descriptors focus on “topic development, organization, and range, accuracy and appropriateness of grammar and vocabulary” (Johnson, 2005, p. 4). Then, this ten-point scale is converted into intervals to make the section have the same scale of listening and GCVR “The writing scale is set at nearly equal intervals between 50 and 100 (53 and 97, to be exact)” (Weigle, 2000, p. 449). For speaking, criteria of judgment include fluency and intelligibility, grammar and vocabulary, interactional skills and functional language use or sociolinguistic proficiency. A holistic scale from one to four is given (Johnson, 2005). The final report of MELAB test includes a score for each part and the final MELAB score, “which is the average of the scores for the writing, listening, and GCVR sections” (Weigle, 2000, p. 450). The Speaking test score is added to the report if the candidate has taken it. The score ranges for each MELAB section are: Part Range Writing 0 –97 Listening 0 – 100 GCVR 0 – 100 Speaking 1- 4 (May include + or -) Final MELAB 0 – 99 (Average of writing, listening, and GCVR scores) (“MELAB Scoring;” n.d.) Statistical distribution of score MELAB Report (2013) provides descriptive statistics for the writing, listening, and GCVR sections as well as for the MELAB final score. Scaled Score Writing Listening GCVR Final Score Minimum 0 31 Maximum 97 98 Median 75 78 Mean 75.97 76.23 St Deviation 8.63 13.28 Distribution of MELAB Speaking Test Scores 21 99 74 72.22 16.15 Speaking Score % Speaking Score % 1 0.34 3- 7.76 1+ 0.57 3 16.44 2- 1.26 3+ 20.32 2 1.48 4- 25.00 2+ 4.68 4 22.15 44 98 75 74.77 11.62 TEST REVIEWS 13 Standard error of measurement Reliability and SEM Estimates for the Listening and GCVR parts are provided in MELAB Report (2013). Listening GCVR Administration Reliability SEM Reliability SEM January/February 0.89 4.40 0.93 3.81 March/April 0.89 4.46 0.94 4.03 May/June 0.89 4.53 0.94 4.05 July/August 0.89 4.47 0.95 3.85 September/October 0.89 4.50 0.95 3.82 November/December 0.87 4.95 0.93 4.04 Evidence of reliability According to MELAB Technical Manual, (as cited in Russell, 2011), MELAB has a high reliability rating. The test/retest reliability coefficient for the MELAB is .91, and the alternate form correlation between two compositions is .89 with a high level of inter-rater reliability, ranging from .90 to .94 for the writing part. Garfinkel (2003) stated that support of the test’s overall reliability is provided through a moderately high and statistically significant correlation between MELAB scores and estimates made by teachers in one small sample" (p. 756, as cited in Russell, 2011). The authors of the test provide content-related evidence of validity for each part of the test in the technical manual by “describing the nature of the skill that the test is intended to measure, the process of test development and a thorough description of the prompts and item types.” They also provide construct-related evidence for validity through “a consideration of the item types on the MELAB in relation to a theory of communicative language ability,” factor analysis and native-speaker performance. Besides, they provide criterion-related evidence of validity through comparing MELAB scores, the MELAB composition and speaking test, comparing MELAB scores with the TOEFL, and comparing MELAB scores with teacher assessments of students’ proficiency (Weigle, 2000, p. 451). Evidence of validity 14 TEST REVIEWS Comparison and Contrast of the Three Tests The teaching context I will work in is Qassim University in Saudi Arabia. Students in this situation include 10 teaching assistants whose ages range from 24 – 30 years old. These students study English to get admission into universities in the United States. They are all female Saudi students coming from different majors, including: Special Education, Psychology, Educational Leadership and Educational Technology. They all have scholarships to obtain their Master’s and Ph.D. degrees in the United States. Furthermore, this group of students has similar degrees of English language proficiency whereby they all are considered high-intermediate to advanced learners of English. Because this program is designed by the university, classes are taught by instructors from the English department in the university. Considering the teaching context and the results of the reviews for each test, I believe that IELTS is the most appropriate test for assessing adult ESL learners in this program in Saudi Arabia. There are several reasons that lead me to this conclusion. Both the IELTS and TOEFLiBT are similar in terms of cost, distribution of testing centers in Saudi Arabia, and organizational acceptance of scores. What makes IELTS unique from other large-scale proficiency exams is that it assesses English as an international language (Uysal, 2010). Assessing students communicative competence that shows their grammatical knowledge of syntax, morphology, phonology and his social knowledge is more important than assessing his usage of standard English because communicative competence is an essential element in speaking English internationally. Test administration is another credit to IELTS over TOEFL iBT. The latter is an online test, while the IELTS is a paper-based test. There is a probability for having technical problems while taking the TOEFL test, such as Internet disconnect which is common in Saudi Arabia. Such a problem may affect the result. Besides, test takers may feel tired from focusing on the screen with just a short break after the first two sections. Not everyone can work effectively on the computer for four hours. Besides, a language learner may write well on paper, but he/she TEST REVIEWS 15 may not be familiar with typing English on the keyboard. IELTS also has another credit in the waiting time for results. A test taker of IELTS has to wait only thirteen days to get his/her result, while he/she has to wait fifteen days for the TOEFL score. Therefore, I can conclude that IELTS is the more appropriate test of determining the level of language proficiency of this group of learners in Saudi Arabia than TOEFL iBT. In contrast, MELAB is the less helpful for those students because it is only accepted by 523 universities in the U.S (“MELAB Recognizing Organizations,” n.d.). Meanwhile IELTS and TOEFL are accepted by over 2,000 universities and colleges in the U.S. Besides, there is limited availability of the MELAB outside the USA and Canada where it is available only as a “sponsored group test arranged by ELIUM,” and the speaking section is not available outside the USA and Canada (“MELAB Recognizing Organizations,” n.d.). In addition, the writing task in this test makes it less effective than IELTS. There are two writing tasks in IELTS, but there is a single task in the MELAB. This is a drawback of MELAB because it might not be representative of a test taker’s actual ability. 16 TEST REVIEWS References Alderson, J.C. & North, B. (1991). (eds.). Language testing in the 1990s. London: Macmillan Publishing Ltd. Breeze, R. & Miller, P. (2011). Report 5: Predictive validity of the IELTS listening test as an indicator of student coping ability in Spain. Retrieved from http://www.ielts.org/PDF/vol12_report_5.pdf. British Council. (n.d.). Choose IELTS. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.http://takeielts.britishcouncil.org/choose Cambridge Michigan Language Assessments. (n.d.). About the MELAB. Retrieved April 20, 2014, from http://www.cambridgemichigan.org/melab Cambridge Michigan Language Assessments. (n.d.). MELAB recognizing organizations. Retrieved April 20, 2014, from http://www.cambridgemichigan.org/sites/default/files/resources/Reports/MELAB-2013Report.pdf Cambridge Michigan Language Assessments. (2013). MELAB report. Retrieved April 20, 2014, from http://www.cambridgemichigan.org/sites/default/files/resources/Reports/ MELAB-2013-Report.pdf Cambridge Michigan Language Assessments. (n.d.). MELAB scoring. Retrieved April 20, 2014, from http://www.cambridgemichigan.org/exams/melab/results Educational Testing Service. (2011). Reliability and comparability of TOEFL iBT™ scores. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.ets.org/s/toefl/pdf/toefl_ibt_research_s1v3.pdf Educational Testing Service. (n.d.). TOEFL iBT® test content. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.ets.org/toefl/ibt/about/content/ Educational Testing Service. (n.d.). TOEFL iBT™ test framework and test development (PDF). Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.ets.org/s/toefl/pdf/toefl_ibt_research_insight.pdf TEST REVIEWS 17 Educational Testing Service. (2011). Validity evidence supporting the Interpretation and Use of TOEFL iBT™ Scores. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.ets.org/s/toefl/pdf/toefl_ibt_insight_s1v4.pdf Hill, K., Storch, N., & Lynch, B. (1999). A comparison of IELTS and TOEFL as predictors of academic success. IELTS Research Reports, 2, 52-63. International English Language Testing System. (n.d.). Band descriptors, reporting and interpretation. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.ielts.org/researchers/score_processing_and_reporting.aspx International English Language Testing System. (n.d.). IELTS™: Information for candidates. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.ielts.org/pdf/Information_for_Candidates_booklet.pdf International English Language Testing System. (n.d.). Predictive validity Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.ielts.org/researchers/research/predictive_validity.aspx International English Language Testing System. (n.d.). Test performance 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2014 from http://www.ielts.org/researchers/analysis_of_test_data/test_ performance_ International English Language Testing System. (2013). Test and Score Data Summary for TOEFL iBT® Tests. Retrieved September 16, 2014, from http://www.ets.org/s/toefl/pdf/94227_unlweb.pdf International English Language Testing System. (n.d.). Test takers FAQs. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.ielts.org/test_takers_information/test_takers_faqs.aspx International English Language Testing System. (n.d.). The proven test with ongoing innovation. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://www.ielts.org/institutions/about_ielts/the_proven_test.aspx TEST REVIEWS 18 Jamieson, J., Jones, S., Kirsch, I, Mosenthal, P. & Taylor, C. (2000). TOEFL ™ framework: A working paper. TOEFL Monograph Series Report, No.16. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service. Johnson, J. (2005). (ed). Spaan Fellow working papers in second or foreign language assessment. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from https://wwwprod.lsa.umich.edu/UMICH/eli/ Home/_Projects/Scholarships/Spaan/PDFs/Spaan_Papers_V3_2005.pdf Lawrence, I. (2008). Validity evidence supporting the interpretation and use of TOEFL iBT™ Scores. TOEFL iBT Research Insight, 4, 1-16. Retrieved from http://www.ets.org/s/toefl/pdf/toefl_ibt_insight_s1v4.pdf Lawrence, I. (2011). Reliability and comparability of TOEFL iBT™ scores. TOEFL iBT Research Insight, 3, 1-7. Retrieved from http://www.ets.org/s/toefl/pdf/toefl_ibt_research_s1v3.pdf MELAB Success. (n.d.). Retrieved April 20, 2014, from http://www.melabsuccess.com/ Russell, B. (2011). The Michigan English Language Assessment Battery (MELAB). Retrieved April 17, 2014, from http://voices.yahoo.com/the-michigan-english-language-assessmentbattery-melab-8793013.html?cat=9 Sawaki,Y. Stricker, L. & Oranje, L. (2009). Factor structure of the TOEFL Internet-Based Test (iBT): Exploration in a field trail sample. ETS, Princeton, NJ. Weigle, S. C. (2000). Test review: The Michigan English language assessment battery (MELAB). Language Testing, 17, 449–455 Uysal, H. H. (2010). A critical review of the IELTS writing test. ELT Journal, 64(3), 314-320.