High/Low Context Cultural Communication Model by Edward T. Hall

advertisement

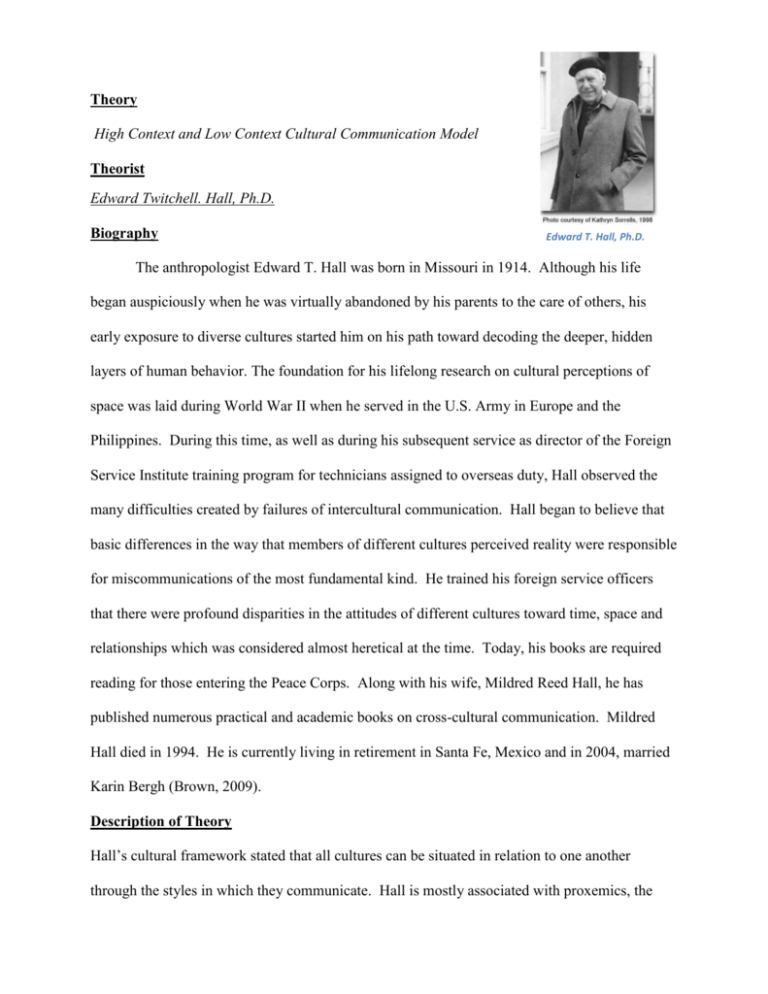

Theory High Context and Low Context Cultural Communication Model Theorist Edward Twitchell. Hall, Ph.D. Biography Edward T. Hall, Ph.D. The anthropologist Edward T. Hall was born in Missouri in 1914. Although his life began auspiciously when he was virtually abandoned by his parents to the care of others, his early exposure to diverse cultures started him on his path toward decoding the deeper, hidden layers of human behavior. The foundation for his lifelong research on cultural perceptions of space was laid during World War II when he served in the U.S. Army in Europe and the Philippines. During this time, as well as during his subsequent service as director of the Foreign Service Institute training program for technicians assigned to overseas duty, Hall observed the many difficulties created by failures of intercultural communication. Hall began to believe that basic differences in the way that members of different cultures perceived reality were responsible for miscommunications of the most fundamental kind. He trained his foreign service officers that there were profound disparities in the attitudes of different cultures toward time, space and relationships which was considered almost heretical at the time. Today, his books are required reading for those entering the Peace Corps. Along with his wife, Mildred Reed Hall, he has published numerous practical and academic books on cross-cultural communication. Mildred Hall died in 1994. He is currently living in retirement in Santa Fe, Mexico and in 2004, married Karin Bergh (Brown, 2009). Description of Theory Hall’s cultural framework stated that all cultures can be situated in relation to one another through the styles in which they communicate. Hall is mostly associated with proxemics, the study of the human use of space within the context of culture. In The Hidden Dimension (1966), Hall developed his theory of proxemics, arguing that human perceptions of space, although derived from sensory apparatus that all humans share, are molded and patterned by culture (See Figures 1 & 2). He argued that differing cultural frameworks for defining and organizing space, which are internalized in all people at an unconscious level, can lead to serious failures of communication and understanding in cross-cultural settings (Brown, 2009). Hall’s most famous innovation has to do with the definition of the informal or personal spaces that surround individuals (Brown, 2009): Intimate space – the closest “bubble” of space surrounding a person. Entry into this space is acceptable only for the closes friends and intimates (Brown, 2009). Social and consultative spaces – the spaces in which people feel comfortable conducting routine social interactions with acquaintances as well as strangers (Brown, 2009). Public space – the area of space beyond which people will perceive interactions as impersonal and relatively anonymous (Brown, 2009). Cultural expectations about these spaces vary widely. In the United States, for example, people that are engaged in conversation will assume a social distance of roughly 4-7’, but in many parts of Europe the expected social distance is roughly half that. When Americans travel overseas, they experience the need to back away from a conversation. In some cultures, communication occurs predominantly through explicit statements in text and speech and they are thus categorized as Low-Context cultures. In other cultures, messages include other communicative cues such as body language and the use of silence. Essentially, High-Context communication involves implying a message through that which is not uttered. This includes the situation, behavior, and para-verbal cues as an integral part of the communicated message. In order to distinguish among cultures, Hall proposed a set of parameters to help situate cultures along a dimension spanning from the High-Context/lowcontent category to the Low-Context/high-content category (Wurtz, 2005). In a high-context culture, there are many contextual elements that help people to understand the rules. As a result, much is taken for granted. This can be very confusing for a person who does not understand the “unwritten rules” of the culture (Changing, 2009). In the low-context culture, very little is taken for granted. While this means more explanation is needed, it also means there is less chance of misunderstanding particularly when visitors are present (Changing, 2009). Hall also distinguished between monochromic time (M-time) and polychromic time (Ptime) to describe two contrasting ways of handling time in different cultures. Typically, M-time people do one thing at a time. In monochromic cultures people tend to have a linear time pattern. North-European and North-American people are normally regarded as being monochromic time people. Polychromic people, on the other hand, like to be involved in many things at once and are committed to people and personal relationships rather than to the job. P-time people are associated with the cyclic time pattern rather than with linear time. Most Asian countries are regarded a polychronic people. P-time people change plans often and easily, whereas M-time people adhere rigorously to plans. Report prepared by: Mary Lou Bledsoe REFERENCES Brown, N. (2009). Edward T. Hall: Proxemic Theory, 1966. Center for Spatially Integrated Social Science. Retrieved October 12, 2009 from http://www.csiss.org/classics/content/13 Changing Minds.org (2009). Hall’s cultural factors. Retrieved October 13, 2009 from http://changingminds.org/explanations/culture/hall_culture.htm Culture at Work (2009). Communicating across cultures. High and low context. Retrieved October 12, 2009 from http://www.culture-at-work.com/highlow.html Edward T. Hall (2009). Retrieved October 12, 2009 from http://edwardthall.com/ Morris, E. S. (2009). Cultural dimensions and online learning preferences of Asian students at Oklahoma State University in the United States. Oklahoma State University. Würtz, E. (2005). A cross-cultural analysis of websites from high-context cultures and lowcontext cultures. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(1), article 13. Retrieved October 13, 2009 from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue1/wuertz.html Figure 1: Diagram of Hall’s High Context Model Note: From Culture at Work (2009). Communicating across cultures. High and low context. Retrieved October 12, 2009 from http://www.culture-at-work.com/highlow.html As shown in Figure 1, the Structure of Relationships in a High Context environment show dense, intersecting networks and long-term relationships, strong boundaries. Relationship is more important than task. Figure 2: Diagram of Hall’s Low Context Model Note: From Culture at Work (2009). Communicating across cultures. High and low context. Retrieved October 12, 2009 from http://www.culture-at-work.com/highlow.html As shown in Figure 2, the Structure of Relationships in a Low Context environment show loose, wide networks and shorter term, compartmentalized relationships. Task is more important than relationships.