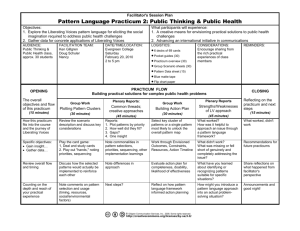

practicum paper - Professional Portfolio Erin K. Kibbey, BS, RN, CCRN

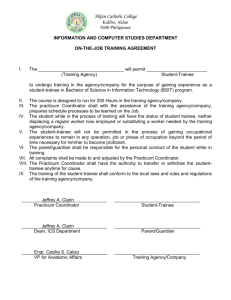

advertisement