AMERICAN PROTEST SONGS

advertisement

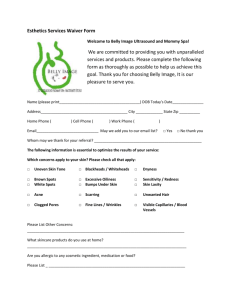

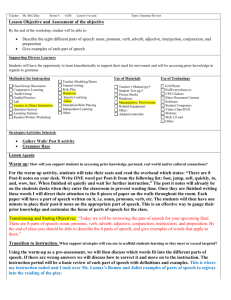

AMERICAN PROTEST SONGS From Leadbelly to Woody Guthrie What is a protest song? A protest song is a song which is associated with a movement for social change and which is connected to current events. The lyrics address topical issues. It may be folk, classical, or commercial in genre. Protest songs are frequently situational, having been associated with a social movement through context. "Goodnight Irene", for example, acquired the aura of a protest song because it was written by Lead Belly, a black convict and social outcast, although on its face it is a love song. VOCABULARY: claim (revendiquer), express grievances (exprimer des doléances), convey a message (transmettre un message), criticize, castigate (fustiger) unfairness, condemn social injustice, support a cause (défendre une cause), advocate social changes (être en faveur de changements sociaux), side with the oppressed (être du côté des opprimés). From the Allan Lomax archive Leadbelly (1885-1949) was an accomplished 12-string guitar player from the Texas-Louisiana border. During his life, Leadbelly served four prison terms for assault. At one of his performances in prison, he was discovered by John Lomax, a Harvard-trained musicologist. Lomax introduced Leadbelly to American audiences of the 1930s and 1940s. Although Leadbelly never sold many records during his lifetime, he strongly influenced several generations of folk musicians. Huddie William Ledbetter was born on Jeter Plantation in Mooringsport, Louisiana, in 1885 into a family that farmed land, first as sharecroppers in Louisiana, then as landowners on the Texas-Louisiana border. Taught to play accordion and then guitar by his uncle, Leadbelly began to employ his talents at local parties. After fathering a second child at age sixteen, Leadbelly was propelled by an outraged community to leave home. He became an itinerant minstrel and a farm laborer. He roamed around Dallas with the legendary blues singer Blind Lemon Jefferson. He got his nickname, Leadbelly, in prison because of his physical toughness. He escaped from prison and returned home, went to New Orleans and lived under the assumed name Walter Boyd. However, he got into a fight with a relative who was shot in the head and killed. Though Leadbelly always maintained his innocence, he was convicted of murder, and was sentenced as Walter Boyd to a long term of hard labor on the Shaw State Farm. His musical gifts served him well in the prison camps, where he became a favorite of the guards. Legend has it that in 1925, Leadbelly pleaded for (and was given) his release in a “please pardon me” song composed for and addressed to Governor Neff. Leadbelly returned to Mooringsport, Louisiana, but his womanizing and rough ways led to another conviction for assault with intent to murder. In the 1930s, the Texas folklorist John Lomax was traveling through the South under a Library of Congress grant, among other things recording the “musical treasury locked up” in the prisons. Lomax discovered Leadbelly at Angola in July 1933. He was astounded by Leadbelly's enormous repertoire and intense vocal style. Using a bulky recorder Lomax began recording Leadbelly. Thème (CONDITIONNELLES) Observez: If the American roots music concert shows in Dijon, I’ll get myself tickets. If Lomax was still alive, he would be surprised at the country revival. If John Lomax had not recorded Leadbelly’s songs, no one would have been aware of his talents. OU Had Lomax not recorded… Traduisez: Si la country redevient populaire, la guitare à 12 cordes sera à nouveau utilisée. Si Guthrie n’avait pas rencontré Leadbelly, il n’aurait pas été influencé par le blues. Si Lomax n’avait pas eu de subvention de la NLC, il n’aurait pas acheté son appareil enregistreur. Si Lomax n’avait pas été soucieux de préserver le patrimoine oral de l’Amérique, il n’aurait pas enregistré les chants de Leadbelly. Si de nouveaux enregistrements de Leadbelly pouvaient être réalisés, les paroles seraient davantage mises en valeur. John A. Lomax is internationally known as the person who spearheaded the Library of Congress's Archive of American Folk Songs with his field recording trips. He, and later his son Alan, were responsible for preserving roots music. Under “double good time” measures adopted to save costs, Leadbelly was released early from prison. Lomax decided to take Leadbelly to New York, where he performed before audiences of musicologists at elite universities, inspiring fear and admiration. The mystique of his convict past and his commanding physical presence, replete with horrific scars, added to his allure. His eclectic repertoire, performed on a twelve-string guitar — which was not widely used then — was largely unknown, and harked back some thirty or more years to near-forgotten rural traditions. John Lomax also wrote a book (Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Leadbelly) with transcripts from his repertoire and explanations of the background of his songs and their place in American folklore. Lomax also arranged a recording contract with the American Record Company, which had recording studios and equipment. However, the commercial success of rural blues had passed some ten years earlier, and the records sold poorly. This was compounded by the company's insistence that Lead-belly record blues rather than the folksongs that dominated his repertoire, most of which predated the blues and were the chief source of his attraction for white audiences. As the stay in New York and environs wore on, the relationship between Lomax and Leadbelly deteriorated, and they parted company in March of 1935. It was John who encouraged Lead Belly to perform in prison clothes, and John who suggested Lead Belly sprinkle his performances with historical context of his songs. As a result, Lead Belly became less blues artist and more novelty act during his partnership with John Lomax. His history as an ex-convict was used in promoting concerts. To the media of the day, Lead Belly wasn't a brilliant artist with a unique voice, he was an example of how the prison system could successfully reform a killer. John Lomax treated Lead Belly as a lecture tool, but what Lead Belly sought was artistic and commercial success. Woody Guthrie Woody came up in a frontier place in Oklahoma, Injun territory, which was new country, in an oil boom. And everything was happening there. The town was full of Injuns, Mexicans, blacks, people from all over the country, and Woody lived in those honky-tonks, and he picked up his guitar, and he learned how to make music that would make sense to all those folks. It was composed of ragtime, hillbilly, blues, of all the currents of his time. He made a new idiom that really represented the opening of this new Western frontier of new highways and power lines and Dust Bowl migrants and all that. It had the sound of movement in it. His guitar has the sound of a big truck going down the highway with the riders bouncing around in the front seat. He wrote America's unofficial national anthem, "This Land Is Your Land." He had the feel of the relationship between language and melody such as nobody else in our time had except maybe his protégé, Bobby Dylan. Alan Lomax THE DUST BOWL The Dust Bowl was the name given to the Great Plains region devastated by drought in 1930s depression-ridden America. The 150,000-square-mile area, encompassing the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles and neighboring sections of Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico, has little rainfall, light soil, and high winds, a potentially destructive combination. When drought struck from 1934 to 1937, the soil lacked the stronger root system of grass as an anchor, so the winds easily picked up the loose topsoil and swirled it into dense dust clouds, called "black blizzards." Recurrent dust storms wreaked havoc, choking cattle and pasture lands and driving 60 percent of the population from the region. Most of these "exodusters" went to agricultural areas first and then to cities, especially in the Far West. THE DUST BOWL Migrant mother, aged thirty-two with seven hungry children, Nipomo, CA )Courtesy of Library of Congress Dust bowl refugees Alan Lomax on Woody and Leadbelly Back in the early 30s, Woody and Lead Belly were musical cronies. At all the New York folk-song parties of that Lead Belly and Woody were the stars. And usually after all of us had decided to go to bed, Woody would go home with Lead Belly and they'd sit up and play until morning. Really, the spirit that Lead Belly and Woody have stems back to the New Deal. That was a time when the whole country was opening up, America was learning about itself. And a great deal of what we learned was through those two guys who suddenly turned up. There was a real affinity between them, I think, because both of them came from a new part of the Western frontier - both came from oil boom towns, in the far west of the South, that is, one from Shreveport, Louisiana, and one from nearby oil-rich hills of Oklahoma. Both of them, therefore, were Western singers, in a sense, and the Western styles sum up the whole of America, where America had got to. And it was a new West. It not only had the sound of cowboy ballads in it, but both of them had the sound of trucks and fast railroads and oil-well pumps and the new opening up of the country, and it also had all the woes that go with it, the feeling of the fragmentation of society that was happening under the pressure of industrialism. Their music has grabbed the attention of the world because it sums up the whole country. It has everything in it: ballads, mountain music, ragtime, jazz, blues, and yet remains a genuine rural folk music that doesn't depart from the canons of that. Basically, they just loved to play together. Woody just absolutely venerated Lead Belly. You see, Lead Belly had gone through an experience that very few other people had gone through and even survived physically. And he came out of these American concentration camps that were the penitentiaries of the South at that time; he came out of it whole and laughing and joyous and confident. And who couldn't admire a person like that? And he had this incredible voice, he had a musical fire that just didn't exist in other people. Even by the 30s, American folk music was being commercialized. And what did that mean? That the guy in back of the glass there, a person who had no knowledge of what the songs actually signified emotionally, was saying, "Oh, put in a little bit more of that, do a little bit more this way. No, no, that's too long. No, speed it up! Slow it down! Stomp your foot harder!" and so forth. Lead Belly and Woody managed to escape that and brought their pure country style right to town.