Gender issues

advertisement

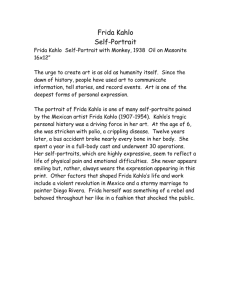

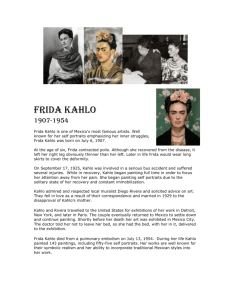

Gender issues Theory notes Frida Khalo • Las Dos Fridas” graphically manifests the wrenching emotional pain of famed Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s divorce from Diego Rivera. On the left is the traditionally dressed, weaker Frida, her broken heart exposed. On the right is the stronger, cosmopolitan Frida, whose intact heart feeds the other Frida. Both hearts are connected to a locket containing a picture of Rivera. Despairing, the weaker Frida attempts to staunch the blood flow from Rivera, which endangers her life. The sky is filled with stormy clouds that convey Kahlo’s (1907 – 1954) agitation, and in profound loneliness, she holds her own hand and is her sole companion • www.art.com • Frida Kahlo employed the symbolism that characterized much of her work in the self-portrait, “Autorretarto con Collre de Espinas y Colibri, 1940.” Wearing a necklace of thorns, Kahlo represents a Christian martyr, and the thorns piercing her skin symbolize the emotional pain of her divorce from artist Diego Rivera. The dead hummingbird is a love charm; the black cat signifies bad luck and death. Kahlo’s pet monkey, a gift from Rivera, represents the devil, and the butterflies in her hair denote the Resurrection. The painting was intended to be a gift for one of her lovers, but after her divorce, Kahlo (1907 – 1954) sold it to pay her lawyer. • “Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair” was the first self-portrait iconic Mexican painter Frida Kahlo created after her divorce from artist Diego Rivera. Renouncing the feminine image depicted in her other self-portraits, Kahlo (1907 – 1954) has just cut off the long hair Rivera admired, and is wearing a suit that was most likely his. Conveying the deep sorrow of her loss, the image appears to express Kahlo’s yearning for the freedom and independence of a man. The large empty space around Kahlo suggests the depth of her loneliness and misery, and the song verse above her reads, “See, if I loved you, it was for your hair, Now you’re bald, I don’t love you anymore.” Frida Khalo Biography • • • From 1926 until her death, the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo created striking, often shocking, images that reflected her turbulent life. Kahlo was one of four daughters born to a HungarianJewish father and a mother of Spanish and Mexican Indian descent, in the Mexico City suburb of Coyoacán. She did not originally plan to become an artist. A polio survivor, at 15 Kahlo entered the premedical program at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City. However, this training ended three years later when Kahlo was gravely hurt in a bus accident. She spent over a year in bed, recovering from fractures of her back, collarbone, and ribs, as well as a shattered pelvis and shoulder and foot injuries. Despite more than 30 subsequent operations, Kahlo spent the rest of her life in constant pain, finally succumbing to related complications at age 47. During her convalescence Kahlo had begun to paint with oils. Her pictures, mostly self-portraits and still lifes, were deliberately naive, filled with the bright colors and flattened forms of the Mexican folk art she loved. At 21, Kahlo fell in love with the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, whose approach to art and politics suited her own. Although he was 20 years her senior, they were married in 1929; this stormy, passionate relationship survived infidelities, the pressures of Rivera's career, a divorce and remarriage, and Kahlo's poor health. The couple traveled to the United States and France, where Kahlo met luminaries from the worlds of art and politics; she had her first solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City in 1938. Kahlo enjoyed considerable success during the 1940s, but her reputation soared posthumously, beginning in the 1980s with the publication of numerous books about her work by feminist art historians and others. In the last two decades an explosion of Kahlo-inspired films, plays, calendars, and jewelry has transformed the artist into a veritable cult figure. Jane Alexander • • • • • Being around this sculpture gives me a very uncomfortable feeling. But what I like about it is the realistic confrontation that it brings out. To me it talks about male destructiveness and the male enjoyment of destroying women. It looks as if the female figure suffered a lot before her death and her body looks disfigured and destroyed; and the title tells me that it wasn't her intention to be like that. I have a feeling that it might have been an action of rape. The quote, "oh yes", seems to imply that. Her hair seems to have been pulled out, and although she is dead her facial expression is one of pain and suffering. Her mouth is slightly open as if she wanted say something. Her body looks rotten, which might imply that she was found a long time after she died. And if you look behind her, she looks as if a post-mortem has been done on her. Her feet are close together, as if on a crucifix, and her shoulder is hanging over the clothes line, as if used to display clothes. Although it is almost unbearable to look at, this sculpture reminds me of recent rapes in our society. It confronts us with reality. This is what people run away from and call a disgrace. The title Stripped ("Oh Yes") girl has several implications as to what the girl was and where she was before she was stripped and killed. She might have been a prostitute who died doing her work or it could have been the rape of an innocent girl. Whatever the case, she was left naked, with no dignity, which is what happens in our society B but people are turning their heads away from it, instead of confronting it. The main focus is on the abuse of women and, to my understanding, this work of art is aimed at confronting people to face the reality of our degenerated world. www.tatham.org.za Diane Victor • She is motivated by a strong negative response to the way people react to each other. • She also favors large figurative drawings of human figures sitting like lumps of rotting meat and harboring all these rotten desires inside - beautifully covered up of course. David Hockney • “Looking through a keyhole” – nude figures of men unposed and relaxed • Men not living up to a stereotype – just being themselves • Personalised view • Titles are often names of the people Hockney draws • Hockney often paints and draws men who are part of the homosexual scene in America. • Image “Ian watching TV” Shirley Goldfarb & Gregory Masurovsky, 1974 • Gregory. Palatine, Roma. Dec. 1974 Tracey Emin • A consummate storyteller, Tracey Emin engages the viewer with her candid exploration of universal emotions. Well-known for her confessional art, Tracey Emin reveals intimate details from her life to engage the viewer with her expressions of universal emotions. Her ability to integrate her work and personal life enables Emin to establish an intimacy with the viewer. Tracey shows us her own bed, in all its embarrassing glory. Empty booze bottles, fag butts, stained sheets, worn panties: the bloody aftermath of a nervous breakdown. By presenting her bed as art, Tracey Emin shares her most personal space, revealing she’s as insecure and imperfect as the rest of the world. • Info from the Saatchi-gallery Lucian Freud • By stripping away the props and accoutrements of some fictional, staged scene—and often the model’s clothing—Freud directs our focus on the person or persons as he views them. These are typically friends and family members. The artist feels a need to know his models. The result is that his familiarity produces such a high level of vulnerability (on the model’s part) and scrutiny (on the artist’s part) that we are drawn past the magnificent surfaces into the hidden psychological aspects below. This forms a grafting of the physical with the psychological. Freud • Freud’s work is often linked to the confident corporeality of his subjects. Rotund figures with excessive mounds of flesh have become a trademark. At times these figures seem little more than an exercise in the mastery of materials. The protuberances of paint are a stand-in for the folds of flesh, though a mere masterful bravado is seldom the end. The starkness of these immense figures within the limits of the studio space provides a glimpse beyond their sheer fleshiness and beyond that sole trait that we most often associate with an obese figure— the immensity of his or her physical body. Freud - Benefits Supervisor Sleeping • Yet all the publicity aside, this painting brings several signature elements of Freud’s work into alignment. The fleshiness and encrusted paint surface are coupled with the placement of the figure inside a studio setting, in a pose that heightens the sense of her physical weight with psychological heft. Still, the work is steeped in the tradition of the male gaze and the complicated heritage that that implies after the introduction of feminist theories. Jenny Saville • • • • • • A physicality that she partially credits to Picasso an artist that she sees as a painter that made subjects as if "they were solidly there....not fleeting" In 1994, Saville spent many hours observing plastic surgery operations in New York. Saville spent long hours observing the work of Dr. Barry Martin Weintraub, a plastic surgeon based in the city. Taking photographs while standing in on cosmetic surgeries and lyposuctions, Saville gained a better understanding of the human body and the various manipulations that can be made through modern medicine. Not only did she improve her knowledge of the physical workings of the alterations, but -- perhaps more importantly -- she gained insight into the psychological factors behind the changes as well. Saville dedicated her career to traditional figurative oil painting. Her paintings are usually much larger than life size. They are strongly pigmented and give a highly sensual impression of the surface of the skin as well as the mass of the body. She sometimes adds marks onto the body, such as white "target" rings. In a society often obsessed with physical appearance, Jenny Saville has created a niche for overweight women in contemporary visual culture. Known primarily for her large-scale paintings of obese women, Saville has recently broken into the contemporary art Saville is lauded for her celebration of paint and her loyalty to oil painting as a medium. In a society of constant technological advancement, Saville has resisted the temptations of using media such as video in her work and has dabbled only briefly with photography. Although Saville finds great inspiration in such media and often sees multiple films per week, these modern fillers are not for her. Instead, she has embraced the physicality of paint and thus has chosen a medium that dates back hundreds of years.In her painting titled “Plan” Saville comments on the need for woman to want to look prettier / be thinner. The contour marks on the flesh is the map where the plastic surgery is to unfold. • Saville’s images are typically viewed through the lens of feminism, but that is too narrow a construction. The paintings that exhibit lines and shapes drawn onto the naked skin of fleshy females (Plan) imply the pre-surgical markings of a plastic surgeon. The artist actually observed plastic surgeries in the year after her art school studies. While there are connections to body image and the pressures placed on women in contemporary cultures—worldwide and not just in the West—the work is more expansive than that. Saville’s figures do not merely exhibit a density of flesh, they often allude to severe physical traumas. The figures are wounded at times, yet the viewer is uncertain whether these are selfimposed traumas or the results of living in a tragic, broken world. Hybrid (1997) seems like a patchwork quilt of skin—a body mismatched to its ill-fitting parts. And this idea of not necessarily feeling at one with the body is a recurring theme in Saville’s work