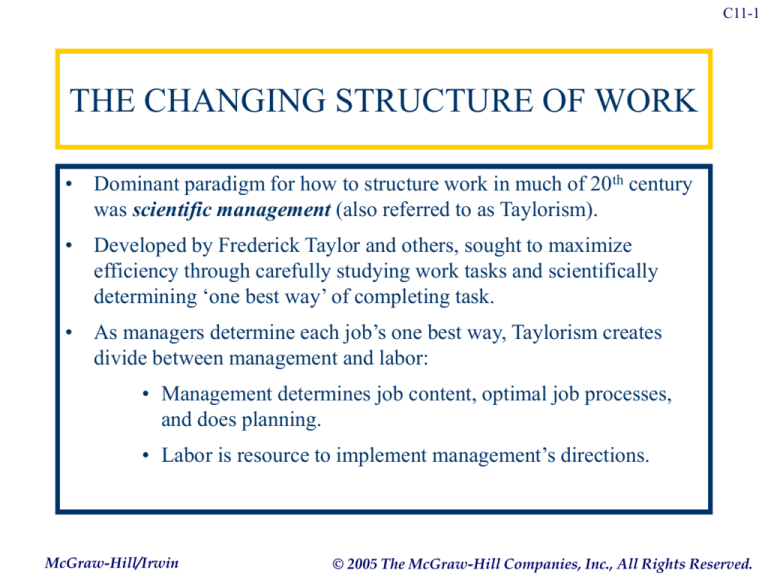

C11-1

THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF WORK

• Dominant paradigm for how to structure work in much of 20th century

was scientific management (also referred to as Taylorism).

• Developed by Frederick Taylor and others, sought to maximize

efficiency through carefully studying work tasks and scientifically

determining ‘one best way’ of completing task.

• As managers determine each job’s one best way, Taylorism creates

divide between management and labor:

• Management determines job content, optimal job processes,

and does planning.

• Labor is resource to implement management’s directions.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-2

THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF WORK

• Bureaucratic control of scientific management well-suited to mass

production of standardized goods and services in stable economy.

• Unstable economic markets in 1970s challenged dominance of mass

manufacturing methods—companies could no longer sell large

quantities of identical products, unable to react quickly to changing

customer demands.

• In addition, repetitive job tasks can cause boredom, alienation, and

mental and physical fatigue which in turn cause absenteeism, turnover,

shirking, and low quality output.

• Both macroeconomic shocks and micro-level issues with employee

satisfaction caused competitive crisis in U.S. business in 1970s,

launched efforts at changing forms of work organization, HR practices,

and business strategies.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-3

NEW BUSINESS MODELS

• Continuous process improvement: Japanese management style

(kaizen) focusing on creating corporate culture of constant change and

incremental improvements.

• Total quality management (TQM) is example of continuous

process improvement strategy.

• Reengineering: reforming business processes, generating large onetime improvements.

• Replacing narrowly focused tasks performed by individuals

with generalists and teams that add value for the organization.

• Workplace flexibility is critical in these new models.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-4

Box 11.5: EMPLOYMENT RELATIONSHIP

FLEXIBILITY

Flexible Employment

Change labor utilization through

varying work hours or number of

employees.

Part-time employment

Temporary employment

Seasonal employment

Lack of sufficient income. Uncertainty.

Periods of unemployment. Stress.

Pay-for-performance

Profit sharing

Ending wage indexation

Risky. Compensation is uncertain and may

decrease. Potential for managerial abuse.

Stress.

Job enrichment

Work teams

Cross-training

Potential for replacing high-wage, skilled

employees with low-wage, unskilled.

Disguised old-fashioned work speed-up?

Stress.

Unilateral management

authority to restructure the

workplace

Lack of a voice in the absence of unions or

works councils. Stress.

Pay Flexibility

Make compensation responsive to

changes in competitive pressures

and organizational performance.

Functional Flexibility

Easily shift workers into different

jobs in response to changing

customer demands and production

needs.

Procedural Flexibility

Change production methods,

technology, and work organization.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-5

JOB CONTROL UNIONISM

• Starts with two management principles for first three-quarters of the

20th century:

• Narrow, standardized jobs (recall scientific management).

• Insistence on maintaining sole authority over traditional

management functions such as hiring, firing, assigning work,

determining job content, and deciding what to produce and

how and where to make it.

• Add in pragmatic union philosophy of business unionism focused on

wages and working conditions.

• What pattern of unionized practices and policies is likely to result?

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-6

JOB CONTROL UNIONISM

• Resulting pattern of traditional unionized practices and policies in

postwar period is called job control unionism.

• Designed to provide industrial justice by protecting workers against

managerial abuse by controlling rewards and allocation of jobs.

• Replaces managerial subjectivity and favoritism with objective

measure of seniority as primary method for determining layoffs,

promotions, and transfers.

• Subjectivity also removed from wage outcomes by closely linking

wage rates to job classifications, not individuals.

• Detailed work rules further control how work is performed and

allocated.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-7

JOB CONTROL UNIONISM

• In mass manufacturing world, job control unionism serves both labor’s

and management’s needs.

• Supported mass-manufacturing requirements for stable and

predictable production.

• Fulfilled union leaders’ needs for countering managerial

authority without having to resort to wildcat strikes which

could undermine their own leadership positions.

• Efficiency and equity were served through peaceful, quasilegal application of workplace rules and contracts that fulfilled

industrial justice; voice was provided through collective

bargaining.

• But the bureaucratic model of job control unionism under fire in 21st

century business model emphasizing flexibility.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-8

Box 11.8: JOB CONTROL UNIONISM

UNDER FIRE

Wages are tied to jobs, not

individuals.

Runs counter to paying for performance—cannot reward individual

merit, productivity, skills, or organizational performance.

Jobs are very narrowly defined.

Difficult to deploy workers to different tasks. Employee boredom

and alienation. Lack of quality and teamwork.

Importance of seniority and

seniority ladders.

Hard to promote the best performers or layoff the worst performers.

Extensive bumping results is disruptive.

Extensive work rules.

Hampers flexibility to move workers around, change job

definitions, and adjust production methods.

Detailed union contracts and

legalistic grievance procedures.

Difficult to break with past practices. Change is slow. Innovation is

stifled.

No employee involvement in

decision-making.

Opportunities for harnessing workers’ ideas for productivity

improvements are limited. Innovation is stifled.

Limited employee voice.

Change is slow. Issues are only solved through formalized

procedures. Problems accumulate until the next round of bargaining.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-9

EMPLOYEE INVOLVEMENT

• Scientific management treats workers as cogs in machine.

• But workers perform their job tasks over and over and

therefore often have good ideas for improving productivity,

increasing quality, and lowering costs.

• Moreover, giving employees discretion in their work can

increase job satisfaction and create better employees.

• Thus, some new business models champion not only workplace

flexibility, but also employee involvement in decision-making.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-10

EMPLOYEE INVOLVEMENT

• Approaches to employee involvement include:

• Quality of working life programs (QWL)

• Quality Circles

• Joint labor-management committees

• Labor representation on corporation’s board of directors.

• The most extensive efforts to restructure workplace involve not only

increasing employee involvement in the decision-making, but also

changing how work is organized.

• High performance work systems of mutually-supporting HR

practices that combine flexibility with employee involvement

in decision-making.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-11

ALTERNATIVES TO SCIENTIFIC

MANAGEMENT

•

•

•

•

Lean Production—Production by work teams with emphasis on quality

through off-line quality circles rather than on-line worker decision-making.

Just-in-time inventories and focus on smooth flow of materials.

• Competitive advantage: price and mass scale quality.

Sociotechnical Systems—Formal, autonomous work teams have

responsibilities for functional as well as routine maintenance tasks plus

continuous improvement.

• Competitive advantage: quality and customization.

Flexible Specialization—Small-scale production of diverse items using

flexible networks of employers.

• Competitive advantage: innovation.

Diversified Quality Production—Quality through broadly-skilled, highlytrained crafts workers.

• Competitive advantage: quality and customization.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-12

DEBATES OVER

HIGH PERFORMANCE WORK SYSTEMS

• Lean production

• Method for continuous quality improvement . . . or

management by stress and disguised old-fashioned speed-up?

• Self-directed work teams

• Unions as valuable business partners . . . or as shirking their

primary role of advocacy for employees’ interests?

• Do slimmer union contracts promote flexibility and increased

employee discretion . . .

• or provide opportunities for managerial manipulation in the

absence of well-defined standards?

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-13

EMPLOYEE REPRESENTATION:

ARE UNIONS REQUIRED?

• Nonunion employee representation plans involve group of employees

meeting with management to discuss employment conditions and to

provide employee voice.

• Note: established by management, management determines

structure, management defines issues covered

• But some plans able to influence management decision-making

and employees’ terms and conditions of employment.

• Significant number of nonunion employee representation plans were

part of welfare capitalism package of HR practices designed to create

motivated, loyal, and efficient workforce.

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-14

THE ELECTROMATION CONTROVERSY

• But other plans were manipulated by management with

primary purpose of preventing employees from forming

independent labor unions.

• As such, the NLRA’s section 8(a)(2) prohibits employer

domination of labor organizations.

– “… any organization of any kind … or Ee representation

committee or plan … in which Ees participate and which exists, in

whole or in part, for dealing with Ers concerning grievances, labor

disputes, wages, rates of pay, hours of employment, or conditions

of work.”

– Unilateral mechanisms such as suggestion boxes by which

individual Ees make proposals are not at issue

– Committees acting with authority delegated by management do not

“deal with” management

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

False Employee Empowerment

As illustrated by Dilbert

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-16

THE ELECTROMATION CONTROVERSY

• U.S. business now argues that section 8(a)(2) prevents

legitimate efforts to increase competitiveness and quality

through employee involvement.

• 1992 NLRB ruling has received great attention.

• In Electromation, several committees ruled to be illegal

company-dominated labor organizations even though

established for legitimate business reasons (not union

avoidance).

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-17

THE ELECTROMATION CONTROVERSY

Polaroid, 329 NLRB No. 47 (1999)

– Decided (3-1) that Employee-Owners Influence Council was a

labor organization dominated by Er

• Co. selected the 30 members, chose topics for input

– Family/medical leave, termination policy, medical benefits, ESOP

– Co. made presentation, Council discussed w/presenter, then were polled

to determine majority sentiment; Co. would later announce decision

• Co. argued that Council’s activities limited to brainstorming and

information sharing, expressing individuals’ views

• Found that Council functioned as bilateral mechanism – in effect

group proposals were made, responded to

• Dissent held that if Council served Er’s purpose of obtaining ideas

upon which to make mngt decision, was not a labor org; was not

presented to Ees as surrogate for U.; did not interfere w/Ees’ sec.7

rights to organize

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-18

THE TEAMWORK FOR EMPLOYEES

AND MANAGERS (TEAM) ACT

• Vetoed by President Clinton in 1996

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.

C11-19

THREE UNIONIZED CHANGE

STRATEGIES

• Escape

• Escaping from company’s bargaining obligation by relocating

operations to nonunion site, subcontracting, or decertifying

union.

• Force

• Pressuring union and employees to accept changes like wage

and work rule concessions through hard bargaining.

• Foster

• Developing new labor-management partnership based on

recognition of both labor and management goals and

opportunities for mutual gain. (e.g., IAM’s High Performance

Work Organization course)

McGraw-Hill/Irwin

© 2005 The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., All Rights Reserved.