Arbitration-Scheduling-Order-2015-06-15

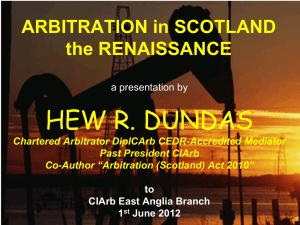

advertisement