Chapter 7 Slides

advertisement

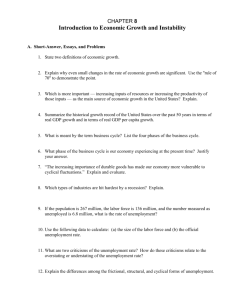

Chapter 7 Unemployment, Inflation, and Long-Run Growth CHAPTER OUTLINE Unemployment Measuring Unemployment Components of the Unemployment Rate The Costs of Unemployment Inflation The Consumer Price Index The Costs of Inflation Long-Run Growth Output and Productivity Growth Unemployment Measuring Unemployment Employed Any person 16 years old or older: (1) who works for pay, either for someone else or in his or her own business for 1 or more hours per week, (2) who works without pay for 15 or more hours per week in a family enterprise, or (3) who has a job but has been temporarily absent with or without pay. unemployed A person 16 years old or older who is not working, is available for work, and has made specific efforts to find work during the previous 4 weeks. Labor Force not in the labor force A person who is not looking for work because he or she does not want a job or has given up looking. labor force The number of people employed plus the number of unemployed. labor force = employed + unemployed population = labor force + not in labor force unemployment rate The ratio of the number of people unemployed to the total number of people in the labor force. unemployment rate = unemployed employed + unemployed labor force participation rate The ratio of the labor force to the total population 16 years old or older. labor force participation rate = labor force population How the BLS Measures Employment Status Includes part time workers 5 Employment Status of the U.S. Population—August 2011 6 How Unemployment is Measured unemployment rate The percentage of the labor force that is unemployed. Computing the unemployment rate for the months of July 2009, July 2011 and July 2015: 2009 Labor force: 154.5 million Employed: 140.0 million Unemployed: 14.5 million 2011 153.2 million 139.3 million 13.9 million Unemployment rate2009 = Unemployment rate2011 = Unemployment rate2015 2015 157.1 million 148.8 million 8.27 million 14.5 .094 9.4% 154.5 13.9 .091 9.1% 153.2 = 8.27 .053 5.3% 157.1 TABLE 7.1 Employed, Unemployed, and the Labor Force, 1950–2012 (1) Population 16 Years Old or Over (Millions) (2) Labor Force (Millions) (3) (4) (5) (6) Employed (Millions) Unemployed (Millions) Labor Force Participation Rate (Percentage Points) Unemployment Rate (Percentage Points) 1950 105.0 62.2 58.9 3.3 59.2 5.3 1960 117.2 69.6 65.8 3.9 59.4 5.5 1970 137.1 82.8 78.7 4.1 60.4 4.9 1980 167.7 106.9 99.3 7.6 63.8 7.1 1990 189.2 125.8 118.8 7.0 66.5 5.6 2000 212.6 142.6 136.9 5.7 67.1 4.0 2012 243.3 155.0 142.5 12.5 63.7 8.1 Note: Figures are civilian only (military excluded). Unemployment Rate for Various Groups July 2015 5.3% 4.6% 6.8% 9.1% 8.3% 5.5% 2.6% Problems in Measuring Unemployment • Official measure of unemployment underestimates the extent of unemployment – Treatment of involuntary part-time workers – Treatment of discouraged workers 10 Problems in Measuring Unemployment • Involuntary part-time workers – Individuals who would like a full-time job but who are working only part time • Discouraged workers – Individuals who would like a job but have given up searching for one 11 Problems in Measuring Unemployment • BLS defines discouraged worker Not working 2. Searched for a job at some point in the last 12 months 3. Currently want a job 4. State that the only reason they are not currently searching for work is their belief that no job is available for them 1. • discouraged-worker effect The decline in the measured unemployment rate that results when people who want to work but cannot find jobs grow discouraged and stop looking, thus dropping out of the ranks of the unemployed and the labor force. • It lowers the unemployment rate! 12 Problems in Measuring Unemployment • Marginally attached to the labor force – Meet the first three requirements of discouraged workers – But not necessarily the fourth: • They can give any reason for not currently searching for work 13 Alternative Measures of Employment Conditions • The Six “U”s – Six different unemployment rates • Each labeled with a “U” followed by a number – “U-3”: the official unemployment rate 14 The Six “U”s http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf Table A-15 15 U-4 U-3 U-6 U-5 U-6 U-5 U-3 U-4 The Duration of Unemployment TABLE 7.4 Average Duration of Unemployment, 1970–2012 Weeks 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 8.6 11.3 12.0 10.0 9.8 14.2 15.8 14.3 11.9 10.8 11.9 13.7 15.6 20.0 18.2 Weeks 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 15.6 15.0 14.5 13.5 11.9 12.0 13.7 17.7 18.0 18.8 16.6 16.7 15.8 14.5 13.4 Weeks 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf 12.6 13.1 16.6 19.2 19.6 18.4 16.8 16.8 17.9 24.4 33.0 39.3 39.4 Alternative Measures of Employment Conditions • The employment-population ratio – Total employment divided by the total population over age 16 – Tracks the fraction of the adult population that is working – not affected by job-searching behavior 18 The Employment Population Ratio: 1948–2015 19 The Employment Population Ratio: 1948–2015 20 Labor Force Participation Rate: 1948–2015 21 Its Not Just Demographics 22 Labor Force Participation Rate: Overall in Blue Along With age 25-54 in Red The Costs of Unemployment Some Unemployment Is Inevitable When we consider the various costs of unemployment, it is useful to categorize unemployment into three types: Frictional unemployment Structural unemployment Cyclical unemployment Frictional Unemployment includes: • people who are between jobs • people who are just entering or reentering the labor market • this is short-term unemployment • these people have skills and they will get jobs 25 Structural Unemployment • Skill mismatch: between workers’ skills and employers’ requirements • Geographic mismatch: between workers’ locations and employers’ locations • Unemployment due to structural changes in the economy that eliminate some jobs and create other jobs for which the unemployed do not have required skills. • This is a stubborn, long-term problem 26 Cyclical Unemployment • Arising from changes in production over the business cycle • A problem for macroeconomic policy 27 Employment and Unemployment • Natural Rate of Unemployment • Sum of Frictional and Structural Unemployment • Full employment • • Zero cyclical unemployment Unemployment at full employment is equal to the natural rate of unemployment Potential output Level of output the economy could produce if operating at full employment 28 Average Unemployment Rates in Several Countries, 1995–2005, 2007 and 2013 2013 10.8% 12.7% 7.2% 7.1% 5.2% 8.0% 6.7% Unemployment rate higher in Europe - primarily structural. •Higher unemployment benefits, for longer periods of time which reduce incentives to accept jobs or acquire skills. •Legal obstacles laying off workers 29 Unemployment rates in the EU compared to Japan and the US •http://epp.eurostat.ec.e uropa.eu/statistics_expl ained/index.php/Unempl oyment_statistics 30 The Costs of Unemployment When the level of real GDP is below potential output • Unemployment rises above the natural rate and employment falls below full-employment rate 31 The Costs of Unemployment Slump A period during which real GDP is below potential and/or the employment rate is below normal Last US Recession End of 2007 through June 2009 32 Real GDP in 2009 Dollars Potential GDP Actual GDP 33 The Costs of Unemployment Economic cost opportunity cost of lost output, output produced is less than the economy’s potential output which means less Income and less consumption 34 The Costs of Unemployment Broader costs • Psychological and physical effects • Setbacks in achieving important social goals • Burden of unemployment not shared equally among different groups in the population • Most heavily: minorities, especially minority youth 35 Measuring Price Level and Inflation • Price Level - average of the prices of all good and services in the economy • Price Index – a measure of the price level • GDP deflator is a price index used to track rise and fall in the price level over time. 36 Index in General • Index - A series of numbers used to track a variable’s rise or fall over time • An index number is calculated as: 37 Example: Index Number for House Prices Year House Price 1 2 3 4 $105,000 $110,000 $125,000 $135,000 Index of House Price 100.00 104.76 119.05 128.57 Note: $110,000/$105,000 = 1.0476 $135,000/$105,000 = 1.2857 The convention is to multiply by 100. Which year is the base period? http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/SPCS20RSA 38 The Consumer Price Index • Consumer Price Index (CPI) – An index of the cost over time of a market basket of goods purchased by a typical household • CPI includes – the part of GDP that consumers purchase as final users – household purchases of used goods such as used cars or used computers – household purchases of imports 39 The Consumer Price Index • CPI does not include – Goods and services purchased by anyone other than consumers – Prices of assets, such as stocks, bonds, and homes • CPI market basket – The collection of goods and services that the typical consumer buys 40 Broad Categories and Relative Importance in the CPI, December 2010 41 Calculating the Consumer Price Index (1) define a market basket (2) determine how much it would cost to purchase the market basket in the current year and in the base year (3) divide the dollar cost of purchasing the market basket in the current year by the dollar cost of purchasing the market basket in the base year (4) multiply the quotient by 100. 42 Calculating the Consumer Price Index 43 Calculating the Consumer Price Index Market Basket using 2011 as the Base Year 44 CPI in 2012 using 2011 as the based period 45 Consumer Price Index, December, selected years, 1970–2010 1983 = 100 46 From Price Index to Inflation Rate • Inflation rate – Percentage change in the price level from one period to the next • Deflation – A decrease in the price level from one period to the next 47 Consumer Price Index, December, selected years, 1970–2010 Year Rate of Inflation 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 48 Consumer Price Index: 1940 - 2014 49 The Rate of Inflation Using the Consumer Price Index, 1950–2014 50 Three Ways the CPI Is Used • (1) As a policy target; • (2) To index payments; • (3) To translate from nominal to real values • Policy target – One macroeconomic goal is stable prices • Index payments – A payment that is periodically adjusted in proportion with a price index such as Social Security retirement income. 51 Translate from Nominal to Real Values • Nominal wage – Number of dollars you earn • Real wage – Purchasing power of your wage 52 Nominal and Real Weekly Earnings (December of Each Year) 2014 $796 236.2 http://www.bls.gov/news.release/wkyeng.t01.htm $337 53 How the CPI Is Used • When comparing dollar values over time – We care not about the number of dollars, but about their purchasing power – Translate nominal values into real values Nominal Value Real Value= 100 Price Index 54 There are Many price indexes • The GDP price index measures the prices of all final goods and services that are included in U.S. GDP • The CPI measures the prices of all goods and services bought by U.S. households including used goods and imports 55 CPI vs. GDP Deflator Prices of capital goods (Investment): – included in GDP deflator (if produced domestically) – excluded from CPI Prices of imported consumer goods: – included in CPI – excluded from GDP deflator The basket of goods: – CPI: fixed – GDP deflator: changes every year The Costs of Inflation • The inflation myth – “Inflation, by making goods and services more expensive, erodes the average purchasing power of income in the economy” • Inflation does not directly decrease the average real income in the economy – because people’s income increase during inflations. Prices and income tend to rise together. Not really hurt. 57 The CPI and Average Hourly Earnings, 1965-2009 900 800 1965 = 100 700 600 500 Real average hourly earnings in 2009 dollars, right scale $10 400 Nominal average hourly earnings, (1965 = 100) 300 200 100 $15 $5 CPI (1965 = 100) 0 $0 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 Hourly wage in May 2009 dollars $20 The Costs of Inflation • But, Inflation changes the distribution of income. – People living on fixed incomes are particularly hurt by inflation. – And the poor have not fared so well. Welfare benefits are relatively fixed and have not kept pace with inflation. Benefits Indexed to Inflation • To address the distribution problem, benefits received by many retired workers, including social security, are fully indexed to inflation. – when prices rise, benefits rise. • If inflation is correctly anticipated – and if both parties take it into account, then inflation will not redistribute purchasing power The Costs of Inflation One way of thinking about the effects of inflation on the distribution of income is to distinguish between anticipated and unanticipated inflation. The effects of anticipated inflation on the distribution of income are likely to be fairly small, since people and institutions will adjust to the anticipated inflation. Unanticipated inflation, on the other hand, may have large effects, depending, among other things, on how much indexing to inflation there is. real interest rate The difference between the interest rate on a loan and the inflation rate. Interest Rates • Nominal interest rate The actual interest rate borrower’s pay and lender’s earn from making a loan • Real interest rate The nominal interest rate adjusted for inflation • Calculation: - real interest rate = nominal interest rate - inflation Example: I borrow $100 from a lender and agree to pay $105 after one year: Loan amount = $100 Interest payment = $5 Nominal Interest rate = $5/ $100 = 5% The lender now has $105 Suppose inflation is 2%. What cost $100 a year earlier now cost $102. The lender’s purchasing power increases by $3 not $5. The real interest rate is 5% - %2 = 3% = Nominal interest rate - Rate of inflation 63 The Costs of Inflation • The real interest rate represents the increase in purchasing power to the lender and the real cost of the loan to the borrower. • If borrowers and lenders know the rate of inflation, they know the real cost and purchasing power of the loan • Unexpected inflation shifts purchasing power The Costs of Inflation • Inflation rate higher than expected – Harms those awaiting payment (lenders) – Benefits the payers (borrowers) • Inflation rate lower than expected – Harms the payers (borrowers) – Benefits those awaiting payment (lenders) Is the CPI Accurate? • Sources of bias in CPI – – – – Substitution bias New technologies Changes in quality Growth in discounting 66 Is the CPI Accurate? • Substitution bias – Quantity is fixed • New technology – CPI: as new products are introduced, CPI overstates inflation • Changes in quality – CPI: fails to fully account for quality improvements in the goods and services in its market basket • Overestimates the price of the basket of goods and services 67 Is the CPI Accurate? • Growth in discounting – CPI: does not recognize that a new discount outlet lowers the prices on many items – As discount outlets expand into new areas, the CPI overstates the inflation rate • Food, electronic appliances, clothing, and other items sold there 68 Is the CPI Accurate? • Consequences of CPI bias – Errors in calculating real wages – Errors in indexing • Retirement benefits, wages, interest payments, or federal tax brackets 69 The Controversy Over Indexing Social Security Benefits • Social Security system – Benefits to about 60 million retired workers in U.S. – One of the largest and most expensive of all federal government programs • More than $770 billion in 2012 • Estimated to grow to $1,400 billion in 2023 • Payments are indexed to CPI 70 The Controversy … • Because the CPI overstate inflation – Nominal payment rises by more than the actual rise in the price level – Benefits payments in real terms increase over time – Purchasing power is automatically shifted toward those who are indexed and away from the rest of society 71 Indexing and “Overindexing” Social Security Benefits 72 Long-Run Growth output growth The growth rate of the output of the entire economy. per-capita output growth The growth rate of output per person in the economy. productivity growth The growth rate of output per worker. Output and Productivity Growth ▲ FIGURE 7.2 Output per Worker Hour (Productivity), 1952 I–2012 IV Productivity grew much faster in the 1950s and 1960s than it has since. ▲ FIGURE 7.3 Capital per Worker, 1952 I–2012 IV Capital per worker grew until about 1980 and then leveled off somewhat. Looking Ahead This ends our introduction to the basic concepts and problems of macroeconomics. The first chapter of this part introduced the field; the second chapter discussed the measurement of national product and national income; and this chapter discussed unemployment, inflation, and long-run growth. We are now ready to begin the analysis of how the macroeconomy works. REVIEW TERMS AND CONCEPTS consumer price index (CPI) productivity growth cyclical unemployment real interest rate discouraged-worker effect structural unemployment employed unemployed frictional unemployment unemployment rate labor force Equations: labor force participation rate labor force = employed + unemployed natural rate of unemployment population = labor force + not in labor force not in the labor force output growth per-capita output growth producer price indexes (PPIs) unemployme nt rate unemployed employed unemployed labor force participat ion rate labor force population