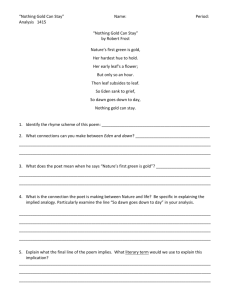

Longman Anthology, p. 2114

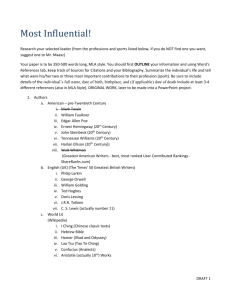

advertisement

The Dawn of the 20th Century The extent of the British Empire, from The Graphic 24 July 1886 The Dawn of the 20th Century British Colonial Possessions in Africa and Asia (in orange) after World War I (Longman Anthology, p. 2119) The Dawn of the 20th Century “Beyond the Pale”: Modern British literature has consistently been distinguished by its movement "beyond the pale." The Pale was originally the fenced-in territory established around Dublin by the invading English in the medieval period, a border between English civilization and Celtic foreignness. In later usage, the phrase "beyond the pale" came to have a purely metaphoric meaning: to stand outside the conventional boundaries of law, behavior, or social class. (Longman Anthology, p. 2111) The Dawn of the 20th Century The Reaction against Victorian Values, Attitudes and Sensibilities British writers and intellectuals of the early twentieth century were disillusioned and disenchanted with the confident, even arrogant assumptions of cultural superiority and moral righteousness of the late nineteenth century, the society known as “Victorian England” in Honor of Queen Victoria, who reigned from 1845-1900. (Longman Anthology, p. 2111) The Dawn of the 20th Century The Foundations of Modern Skepticism—twentieth century writers and intellectuals do not share the Victorian confidence in a universal moral order or in divine justice: In Conrad's Heart of Darkness, the narrator Charlie Marlow suffers from a similar moral vertigo. When, at the novella's close, he resolves to perform an action he finds deeply repugnant-to tell a lie-he worries that his willful violation of the moral order will provoke an immediate act of divine retribution. None, however, is forthcoming: "It seemed to me that the house would collapse before I could escape, that the heavens would fall upon my head. But nothing happened. The heavens do not fall for such a trifle." In works like these, a voyage is undertaken into a vast, unknown, dark expanse. Those few who come out alive have seen too much ever to be the same. (Longman Anthology, p. 2114) The Dawn of the 20th Century The death of God—Nietzsche: In The Joyful Science (1882) Friedrich Nietzche proclaimed “God is dead”: The point is not exactly whether or not there is a God; rather, in modern society almost no one has the same kind of relationship to God that the typical believer had in the middle ages. • Modern societies depend upon science as a solution to problems • Modern societies emphasize the personal development of individual humans rather than duty to one’s “superiors” (seen as the divinelyordained authorities of a social hierarchy) (Longman Anthology, p. 2114) The Dawn of the 20th Century The death of God—Nietzsche: In asserting that “God is dead” Nietzsche was suggesting that traditional religion had been discredited by advances in the natural and physical sciences, and as transcendent standards of truth disappeared, so logically must all moral and ethical systems depending on some faith for their force. It was from this base that Nietzsche created the idea of the Übermensch, the "superman" who because of his intellectual and moral superiority to others must not be bound by social conventions. Conrad's tragic figure Kurtz and [George Bernard] Shaw's comic Professor Henry Higgins represent two very different takes on this idea, building on Nietzsche's interest in showing how all values are "constructed" rather than given-at some level arbitrary, all truths being merely opinions, all social identities merely roles. (Kevin Dettmar and Julia Wicke, Longman Anthology, p. 2114) The Dawn of the 20th Century The social construction of reality: Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams (1900) and Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901) together illustrate in an especially vivid way his evolving theories about the influence of the unconscious mind, and past (especially childhood) experience, on our daily lives. (Kevin Dettmar and Julia Wicke, Longman Anthology, p. 2114-15) The Dawn of the 20th Century Einstein problematizes Newtonian physics: A further intellectual shock wave was the revolution in physics that was spearheaded by Albert Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity (1905). In both this theory (dealing with motion) and later in the general theory of relativity (dealing with gravity), Einstein shook the traditional understanding of the universe and our relationship to it; the certainty and predictability of the Newtonian description of the universe had been undone. (Kevin Dettmar and Julia Wicke, Longman Anthology, p. 2115) The Dawn of the 20th Century Heisenberg’s “Uncertainty Principle”: The "uncertainty" of Einstein's universe was seemingly reinforced by developments in quantum physics, such as the work of Niels Bohr (who won the Nobel Prize in physics in 1922) and Werner Heisenberg, author of the famous "Uncertainty Principle" and the principle of complementarity, which together assert that the movement of subatomic particles can only be predicted by probability and not measured, as the very act of measurement alters their behavior. Ironically enough, the true import of these ideas is not, as the truism has it, that "everything is relative"-in fact, Einstein says almost the exact opposite. In Einstein's vision of the world, nothing is relative: everything is absolute, and absolutely fixedexcept for us, fallible and limited observers, who have no secure standpoint from which "to see the thing as in itself it really is," to quote Matthew Arnold's 1867 formulation of the critic's goal. (Kevin Dettmar and Julia Wicke Longman Anthology, 2115) The Dawn of the 20th Century Moral Ambiguity: The modern writer was faced with an enormous, Nietzschean task: to create new and appropriate values for modern culture, and a style appropriate to those values. As a consequence, there is often a probing, nervous quality in the modernist explorations of ultimate questions. This quality can be seen at the very start of the century in Conrad's Heart of Darkness, a novel about psychological depth and social disintegration that simultaneously implicates its readers in the moral ambiguities of its events. These ambiguities, moreover, are reflected in the very presentation of the narrative itself. In the modern novel, we are no longer allowed to watch from a safe distance while our protagonists mature and change through their trials; instead, we are made to undergo those trials ourselves, through the machinations of the narrative. (Kevin Dettmar and Julia Wicke, Longman Anthology, p. 2116) The Dawn of the 20th Century Marx—Urbanization, Industrialization and Alienation: Paralleling the new social and artistic opportunities of the twentieth century was a kind of anomie ,or alienation created by the rush toward industrialization. Vast numbers of human figures remained undifferentiated and the mass-manufactured hats and clothing worn by British industrial workers served only to heighten the monotony of their daily routines. Newspapers eagerly published photographs of thousands of sooty-faced miners. The members of the workforce, which Marx had called "alienated labor," were seen to be estranged not just from their work but from one another as well, as they themselves became mass products. This situation is dramatized especially vividly in the silent films of the period-from the dystopian vision of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926) to the more comic vision presented by the British-American Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times (1936). (Kevin Dettmar and Julia Wicke, Longman Anthology, p. 2119-20) The Dawn of the 20th Century Charlie Chaplin, from Modern Times (1936) The Dawn of the 20th Century Charlie Chaplin, from Modern Times (1936) The Dawn of the 20th Century Mad scientist and Android, scene from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1936)