Session 15 Fortunati Handout 352.3k - Illinois Association of School

advertisement

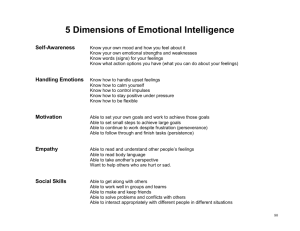

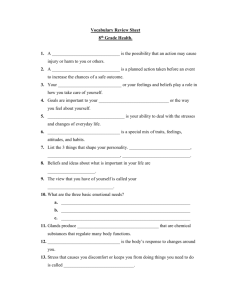

School Based Interventions for Children with Incarcerated Parents: Identifying and Treating Issues Katelen Fortunati, LCSW Amber Jennings, MA Chestnut Health Systems 2015 Outline • • • • • • • • The Impact Characteristics of the Client The Experiential Process Categories and List of Treatment Areas Scale and Treatment Plan Therapeutic Messages and Themes Overview of Intervention Programs Change Maintenance The Impact • • • • 2.7 million children nationwide Racial differences Mother vs. father caregiving profiles ACEs (http://acestoohigh.com) • Long-term effects Characteristics of the Client • Impact of trauma • Risks of parental incarceration • • • • Economic Family instability Health disparities Police/welfare contact • Child development • Case example Ambiguous Loss • “…ambiguous loss is the most stressful kind of loss. It defies resolution and creates long-term confusion about who is in or out of a particular couple or family. With death, there is official certification of loss, and mourning rituals allow one to say goodbye. With ambiguous loss, none of these markers exist. The persisting ambiguity blocks cognition, coping, meaning-making and freezes the grief process.” (Boss, et al. 2003) Types of AL • Type 1: physical absence and psychological presence • Case example • Type 2: physical presence and psychological absence • Case example Ambiguous Loss • Characteristics of the construct – Ambivalence – Traumatizing – Freezes the grief process – Closure improbable – Grieving the loss Ambiguous Loss • Core assumptions – Relational phenomena – not an individual condition – Positive psychology – assumed a natural resiliency – Occurs in multiple levels – Process occurs both linear & systemically meta-recursive process Ambiguous Boundaries • Theoretical suggestions: (Boss, et al 2005) – Higher the boundary ambiguity in the family system, the higher the family stress and greater individual and family dysfunction. – If a high degree of family boundary ambiguity persists overtime, the family system will become highly stressed and subsequently dysfunctional. Ambiguous Boundaries • Families with varying belief systems (e.g., mastery vs. fatalism) will differ in how they perceive their family boundaries, even after similar events of loss or separation. • The length of time a family will be able to tolerate a high degree of boundary ambiguity will be influenced by the family’s value orientation (e.g., mastery vs. fatalism). • The family’s perception (definition) of an event will be influenced by the larger community context. Rando’s 6 “R” Process Model for Complicated Grief (Rando, 1993) • Avoidance phase • RECOGNIZE the loss • Confrontation phase • REACT emotionally to the separation • RECOLLECT and RE-EXPERIENCE the lost parent • Accommodation phase • RELINQUISH • READJUST to daily life • REINVEST or adopt new ways of being in the world • Meaning Reconstruction Rando’s 6 “R” Process Model for Complicated Grief • Seek to provide new understanding of attachment (Klass et al, 1996) • Continued attachment does not equal unresolved grief • Disengagement and letting go of the past does not have to be a goal of grief • Enduring bonds can be healthy – they search for ways to maintain a connection • Each child’s response is unique • MEANING RECONSTRUCTION is the central process (Neimeyer, 2003) Experiential Process Phases of Parental Incarceration • Initial Phase • Shock / confusion / avoidance • Need to recognize the loss • Denial • Need to recollect lost parent • Anger / Resentments • Need to react emotionally to the separation • Lower Level Acceptance / Accommodation • Realization of situation/family dysfunction • Need to relinquish and readjust Experiential Process Phases • Advanced acceptance • Family member is working on own challenges • Letting go or forgiveness • Need to reinvest or adopt new ways of being • Possible re-unification of family unit • Restorative Justice • Parent takes responsibility • Parent apologizes Variation of Individual Challenges • Vary depending upon the following factors: – Level of trauma – Level of attachment – Attitudes and core beliefs/schemas – Resiliency factors – Coping skills/self-regulation – Suppression/repression – Individual resources List of Potential Challenges • Attachment separation/grieving issues: – Appears to be grieving the loss – Denial what happened – Acknowledges what happened, but emotionally negotiates – Harbors resentments and hostility – Feels abandoned – Hasn’t exhibited forgiveness – Doesn’t feel validated – Feelings of being loved and attachment with parent List Of Potential Challenges • Attachment separation/grieving issues: – – – – – – Emotionally refuses the reunification Appears to blame self Lacks friends (social networks) Lacks a support system Withdraws from people (isolates) Appears depressed List Of Potential Challenges • Regulations Skills – – – – Anger management (has problems controlling temper) Problem solving problems Problems with coping skills Goal setting problems List Of Potential Challenges • Trauma Related Issues – – – – – – – – – – Has anxiety and seems stressed Traumatized (distressed about it) Avoids conversations about the events Appears in shock Appears confused Seems to dissociate (detach) Has flashbacks Appears easily startled Can’t focus Has nightmares/terrors List Of Potential Challenges • Self Concept Related – – – – – – – – – Under plays strengths Lacks confidence Sense of identity Doesn’t seem empowered Insecurity/inferiority Self-esteem (doesn’t feel good about self) Self-worth (doesn’t seem to value self) Doesn’t feel okay (adequate about self) Personal hygiene issues Therapeutic Messages and Themes • Key Therapeutic Messages – – – – – Core belief/schema Empowerment Sense of self–efficacy Vision of hope Acceptance of external realities Therapeutic Messages and Themes • Key Treatment Themes – – – – – – – – Understanding what happened Dealing with shame and blame Acknowledging trauma and grief Dealing with feelings and managing anger Building and reaffirming a positive identity Building good relationships Building good support systems Planning for the future Theoretical Assumptions • People have choices and are self-determined • All behavior has meaning • People have needs that can be met functionally or through dysfunction • Holistic view • The person consists of different experiential domains, including cognitive (thinking, beliefs), affective (emotions, feelings), behavioral, social, bio-physiological- body functions, spiritual, contextual (environmental, situational), senses. Theoretical Assumptions • People can continuously learn. • People continuously change and develop. • Traumas can impact learning and development. Foundation disruption • Learning is complex, multi-leveled, and dimensional. A lot of learning involves “states.” • Change is creating a difference within functioning. Dimensions of Self • Multiple Experiential Domains of Self – – – – – – – – Cognitive thoughts, ideas, attitudes Affective emotions, moods, feelings Behavioral overt (motor) activities Spiritual connection to higher power/meaning Biological-Physiological organs, chemistry Socially attachment, relationships Contextual background, environmental Sensory Modalities perceptual modes • Core: Mind-Body Connection Core Perceptual Belief System (State Dependent Memory Learning) Holistic View: Mind-Body Connections Cognitive Social Contextual Perceptual Belief System Mind- Body Spiritual Affective Behavioral BioPhysiological Good Lives Model (Ward, 2002) • Fragmented/poor plan - leads to a chaotic meandering • Coherent plan - leads to a realistic plan tied to abilities, preferences, living environment. • In life - it is about how we meet our needs • People seem to fluctuate, however, the goal is to hopefully live mostly in a coherent life plan Program Parameters: Manuals vs. Process • Programs need to be planned and documented via manuals – Manuals are the guidelines and program map – Therapist style delivery of interventions and process variables account for large percent of successful outcome – Flexibility vs. rigidity – Common Factors – Dr. Sean Davis • Process is key – Experiential processes activated • Responsiveness Key Factors in Successful Programs • • • • • Respect and Rapport Therapeutic Connection Hope Encouragement Directive – Structure and Guidance – Flexible with minimal chaos Early Intervention with Children of Incarcerated Parents • Chestnut Recovery Values • • • • • Hope Empowerment Health and Wellness Respect Spirituality and Connectedness • Program Requirements • Comprehensive Services – – – – – – Case Management (advocacy) Therapy (individual, family, group) Psychiatric Services Caregiver Supports Transportation Grant Funded Lutheran Social Services Curriculum: Session Structure • • • • • Psycho-educational group CBT combined with positive psychology Holistic approach 8 sessions Currently piloted in a Chicago middle school Sessions 1. Understanding What Happened – Instilling hope – Looking at the reality of the situation 2. Dealing With Shame and Blame – Bill of Rights – Ownership: Taking on the blame 3. Acknowledging Trauma and Grief – The impact – Identifying feelings – Grieving process of the loss and feelings Sessions 4. Dealing with Feelings and Managing Anger – Identifying feelings – Range of feelings – The levels of feelings 5. Coping with Anger and Resentments – – – – Managing anger Coping skills Letting go/ forgiveness Coping with anger and resentments Sessions 6. Building and Reaffirming a Positive Identity – Feeling OK – Realizing and buying into the fact that “life isn’t fair but I’m OK.” – Using strengths – Building strengths – Affirmations – Validation Sessions 7. Building Good Relationships and Good Support Systems – – – – Respect self & others Empathy Boundaries Developing good support systems 8. Planning for the Future – – – – – Instilling hope Goal setting (immediate, medium, long range) Realistic or not Steps to complete goals Keeping hope Essentials of Change Maintenance • Change maintenance is based on a dynamic change process involving all experiential domains at varying levels • Self- determined • Restore and/or enhance resiliency • Coping skills • Reunification Key Essential Elements • Change in core beliefs: – – – – – “Life isn’t fair but I’m ok” “The past doesn’t control me, I control me” “I’m ok and worthy” “It is not my fault” “I can do this” • Re-organizing the meaning of the experience into healthy/functional • Empowerment/mastery of problems • Acceptance of the situation for what it is • Normalizing the situational experience • Release of emotional energy and letting go of issues • Feeling connected to someone again Concluding Thoughts • The impact of losing a parent to incarceration varies but is significant. • There is an experiential process - sometimes described as the ambiguous loss. • Treatment can be effective, thus reducing the impact. • Programs have been outlined, with clinical examples • Recovery is a dynamic process, often doesn’t follow a clean linear trajectory • There are key essential elements to the process of recovery (mastery, empowerment, letting go of issues, releasing energy,…) Contact • Katelen Fortunati, LCSW – katelen.fortunati@gmail.com – Children’s book information • http://www.safersociety.org/foundation/ • Amber Jennings, MA – anjennings@chestnut.org References • • • • • • • • • Bender. J. M. (2010). My daddy is in jail: Story, Discussion Guide, & Small Group Activities for Grades K-5. Chapin, SC: Youthlight, Inc. Boss, P., Greenberg, J. & Pearce-McCall, D. ( ). Measurement of Boundary Ambiguity in Families. Station Bulletin, 593-1990 Boss, P., Beaulieu, L., Weiling, E., Turner, W. & LaCruz, S. (2003). Healing Loss, Ambiguity, and Trauma: A Community-Based Intervention with Families of Union Workers Missing After The 9/11 Attack in New York City. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 29, 455-467. Burgess, S.; Caselman, T.; & Carsey, J. (2009). Empowering: Children of Incarcerated Parents. Chapin, SC: YouthLight Inc. Cassidy, J., Poehlmann, J., & Shaver, P. (2010). Introduction to the Special Issue: An attachment perspective on incarcerated parents and their children. Attachment & Human Development, 12, 285-288. Clopton, K. & East, K. (2008). “Are There Other Kids Like Me?” Children With a Parent in Prison. Early Childhood Education Journal, 36, 195-198. Dept. of social & Health Services, Washington State (Dec. 2009). A behavioral health toolkit for providers working w/children of the incarcerated & their families. Geller, A., Garfinkel, I., Cooper, C., & Mincy, R. (2009). Parental Incarceration and Child WellBeing: Implications for Urban Families. Social Science Quarterly, 90. Initiative Foundation (Date unknown) How to explain jails & prisons to children. Initiative Foundation, 405 1st dtreet SE, Little Falls, MN 56345, 877-632-9255. References • • • • • • • • • • Johnson, E. & Easterling, B. (2012). Understanding Unique effects of Parental Incarceration on Children: Challenges, Progress, and Recommendations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 342356. Klass, D., Silverman, P.R., & Nickman, S.L. (Eds.). (1996). Continuing Bonds. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis Lander, I. Towards the Incorporation of Forgiveness Therapy in Healing the Complex Trauma of Parental Incarceration. Child Adolescent Social Work Journal, 29, 1-19. McMurran, M. & Ward, T. (2004). Motivating offenders to change in therapy: An organizing framework. Legal & Criminological Psychology, 9, 295-311. Miller, K. (2006). The Impact of Parental Incarceration on Children: An Emerging Need for Effective Interventions. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 23. Neimeyer, R.A. (Ed.). (2003). Meaning Reconstruction & the Experience of Loss. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Newby, G. (2006). After Incarceration: Adolescent-Parent Reunification. The Prevention Researcher, 13. Phillips, S. & Gates, T. (2011). A Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Stigmatization of Children of Incarcerated Parents. Journal of Children and Family Studies, 20, 286-294. Rando, T.A. (1993). Treatment of Complicated Mourning. Research Press Reilly, K. (2013). Sesame Street Reaches Out to 2.7 million American Children With an Incarcerated Parent. Pew Research Center References • • • • Shlafer, R., Poehlmann, J., Coffino, B., & Hanneman, A. (2009). Mentoring Children with Incarcerated Parents: Implications for Research, Practice, and Policy. Family Relations, 58, 507-519. Sprenkle, D. H., Davis, S. D., & Lebow, J. L. (2009). Common factors in couple and family therapy: The overlooked foundation for effective practice. New York: Guilford Press. Ward, T. (2002). Good lives & the rehabilitation of offenders: Promises & problems. Aggression & violent Behavior, 7, 513-528. Ward, T. (2002b).The management of risk and the design of good lives. Australian Psychologist, 37, 172-179.