Contact Information - Rural Institute

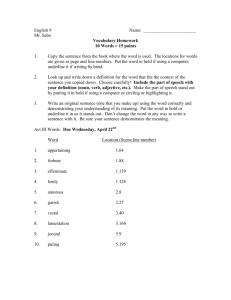

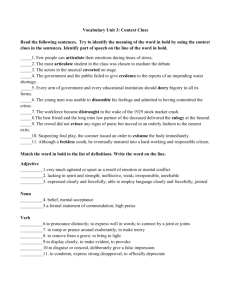

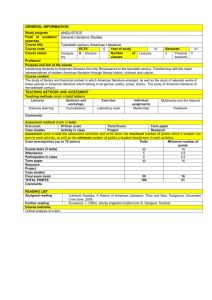

advertisement