PracticalCopyright - University of Illinois - Urbana

advertisement

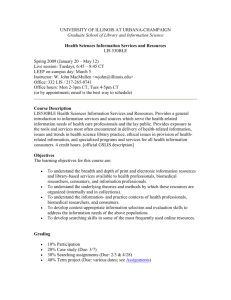

Practical Copyright Considerations for Teaching and Research Janice T. Pilch University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign February 24 and 26, 2009 Copyright in teaching and research • Creation and use of copyrighted works is essential to the educational and research activities of universities • Students and faculty create their own copyrighted works • Students and faculty use copyrighted works in teaching, research, and scholarship U.S. copyright law functions to maintain balance between rights of copyright holders and rights of people to use works. There are privileges and responsibilities on both sides. The basics of U.S. copyright law Copyright Act of 1976 (17 United States Code) http://www.copyright.gov/title17 • Requirements for copyright protection in U.S. – Originality – Minimal creativity – Fixation in tangible medium of expression • Copyright exists upon creation of the work – Since 1989 copyright notice no longer required in U.S. (© with year of first publication and name of copyright owner) • Jurisdiction of U.S. copyright law - Applies to U.S. works and eligible foreign works being used in the U.S. What is protected by copyright in U.S. Literary works Musical works, including any accompanying words Dramatic works, including any accompanying music Pantomimes and choreographic works Pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works • Works of visual art Motion pictures and other audiovisual works Sound recordings Architectural works What is not protected by copyright in U.S. • Facts, ideas, procedures, processes, systems, methods of operation, concepts, principles, discoveries • U.S. federal government works • Works in public domain Who owns copyright in a work • Authors (initial authorship) • Employers in works made for hire (in some countries employees, as defined by law of country of origin) • Heirs or other special beneficiaries; transferees Exclusive rights of copyright holders in U.S. 1. Reproduction For example: quoting, photocopying, digitizing, printing, downloading, posting to a website 2. Preparing a derivative work For example: creating a translation, abridgement, annotated version, revised version, film based on book, drama based on novel, collage, musical arrangement 3. Public distribution For example: making a work publicly available on a website or other electronic forum where it can be copied Exclusive rights of copyright holders in U.S. 4. Public performance For example: showing a motion picture for a public audience, streaming a video to the public 5. Public display For example: Placing works on a website where they can be publicly viewed; publicly displaying still shots from a film; publicly displaying photographs 6. Public performance by means of a digital audio transmission For example: streaming a recorded song to the public [Section 106] Summary of U.S. copyright terms – If published before 1923, in public domain – If published with notice from 1923-1963 and renewed, 95 years from date of publication – If published with notice from 1964-1977, 95 years from date of publication – If created, but not published, before 1978, life of author + 70 years or 12/31/2002, whichever is greater – If created before 1978 and published between 1978 and 12/31/2002, life of author + 70 years or 12/31/2047, whichever is greater Summary of U.S. copyright terms – If created from 1978- , life of author + 70 years (for works of corporate authorship, works for hire, anonymous and pseudonymous works, the shorter of 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation) – If published without notice from 1/1/1978-3/1/1989 and registered within 5 years, or if published with notice in that period, life of author + 70 years (for works of corporate authorship, works for hire, anonymous and pseudonymous works, the shorter of 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation) * For U.S. works, registration and renewal records in U.S. Copyright Office will be relevant; for certain foreign works, this may also be relevant. Resources on copyright terms and status of works See charts by: • Laura Gasaway http://www.unc.edu/~unclng/public-d.htm • Peter Hirtle http://www.copyright.cornell.edu/training/Hirtle_Public_Domain.htm • U.S. Copyright Office, Circular 22, How to Investigate the Copyright Status of a Work http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ22.pdf • U.S. Copyright Office database of copyright records (Jan. 1, 1978- ) http://www.copyright.gov/records • Stanford Copyright Renewal Database (for books 1923-1963) http://collections.stanford.edu/copyrightrenewals/bin/page? forward=home Fair use Certain limitations and exceptions to copyright enable use of copyrighted works without prior permission of the copyright holder or payment of a royalty. Fair use is one of these. “Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include — Fair use (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.” [Section 107] Fair use • Establishes that certain uses are not infringing, depending on 4 factors, for purposes including criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, and research • Applies to all types of works, published and unpublished, and all formats (technology neutral) • Broad and ambiguous • But does not guarantee against infringement Weighs for fair use: • Purpose: Education, research, criticism, comment, news reporting, transformative use, parody, non-commercial use • Nature: Published, work of factual nature, informational, nonfictional • Amount: Small portion, non-essential portion • Effect: No major effect on market or potential market for work Weighs against fair use: • Purpose: Commercial use, entertainment, nontransformative use • Nature: Unpublished, highly creative work • Amount: Large portion, “heart” of the work • Effect on market: Affects market or potential market for work • See Checklist for Fair Use, in Kenneth D. Crews, Copyright Law for Librarians and Educators: Creative Strategies and Practical Solutions, 2d ed. (Chicago: American Library Association, 2006), 124. Importance of transformative use in the academic environment “ If … the secondary use adds value to the original—if the quoted matter is used as raw material, transformed in the creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings—this is the very type of activity that the fair use doctrine intends to protect for the enrichment of society.” Pierre N. Leval, “Toward a Fair Use Standard” Harvard Law Review 103, 5 (March 1990): 1111 Fair use cases • Harper & Row, Inc. v. The Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539 (1985) About 300 words from an approx. 30,000-page manuscript. Not a fair use. • Salinger v. Random House, Inc., 811 F.2d 90 (2d Cir.), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 890 (1987) Large portions of unpublished letters by J.D. Salinger paraphrased by a biographer for publication in a book. Not a fair use. • Wright v. Warner Books, Inc., 953 F.2d 731 (2d Cir. 1991) Quotes from 6 unpublished letters and 10 unpublished journal entries, not more than 1% of Wright’s unpublished letters used in a scholarly biography. A fair use. • Sundeman v. The Seajay Society, Inc., 142 F.3d 194 (4th Cir. 1998) Scholar used quotations from an unpublished literary manuscript in research paper presented at academic conference. A fair use. Fair use cases • Penelope v. Brown, 792 F. Supp. 132 (D. Mass. 1992) Writer of manual for aspiring authors used examples of sentences taken from a book on English grammar and usage, in 5 pages of a 218-page book. A fair use. • Higgins v. Detroit Education Broadcasting Foundation, 4 F. Supp. 2d 701 (E.D. Mich. 1998) 45 seconds of a short song were used as background music in a television program broadcast on a PBS affiliate, which also sold copies of the program to educational institutions for educational use. A fair use. Transformative use was a factor. Sources: • Stanford Copyright and Fair Use website, http://fairuse.stanford.edu/Copyright_and_Fair_Use_Overview/ chapter9/index.html • Kenneth D. Crews, “Court Case Summaries,” http://www.copyright.columbia.edu/court-case-summaries Fair use: Using copyrighted works in research • Term papers, assignments, projects, classroom presentations, publications • Theses and dissertations • Proquest UMI website: http://www.proquest.com/en-US/products/ dissertations • University of Illinois Graduate College, Thesis Handbook 2008-2009: http://www.grad.uiuc.edu/thesis/200809_Thesis_Handbook_FINAL.pdf UIUC Graduate College Guidelines for ETDs “Material for which reprint permission is required includes, but is not limited to, figures, tables, illustrations, and substantial portions of text, which are generally defined as the lesser amounts of either 300 words or 10 per cent of the whole. Permission is also required to reprint works of a student’s own authorship to which the student no longer retains the copyright. In such cases, the student will need to contact the current rights-holder. ” -From Copyright Memo of Richard Wheeler, Vice Provost and Dean, Graduate College, on Thesis Requirement for Copyright Permission from Others, January 16, 2008 Fair use: Using copyrighted works in research • Reasonable, limited, educational, scholarly uses of materials are more likely to be fair use • Consider whether the use will involve print-only access, restricted Web access, or public Web access • Publication and digital distribution create more copyright considerations • Limit to amount needed to meet goals of research • Read publishers’ policies and guidelines carefully • Be familiar with UMI Proquest policies and guidelines for theses and dissertations • Always credit the source Fair use scenarios for research Is it necessary to seek permission from the copyright holder? Scenario 1. A graduate student would like to use excerpts from unpublished letters written by a noted scholar and located in the University Archives, in a paper that she hopes eventually to publish as a journal article. Scenario 2. A student would like to use several nature photographs from a photography book published in 1980 in his term paper on environmental change. Scenario 3. A graduate student would like to use several nature photographs from a photography book published in 1980 in her dissertation on environmental change. Fair use scenarios for research • Scenario 4. A student would like to create a multimedia presentation for a media studies class, to include excerpts from textual works, from sound recordings and from documentary films, as well as images taken from the Web and digitized from books in the library. • Scenario 5. A scholar would like to copy news articles on the war in Iraq from the Internet and from library newspaper databases, to store in a computer file for her own research. Using copyrighted works in face-to-face teaching • U.S. copyright law allows for performance and display of works in face-to-face teaching activities of nonprofit educational institutions – In a classroom or similar place devoted to instruction – Requires that when using a motion picture or other audiovisual work, the copy used must be lawfully made [Section 110(1)] • This enables presentation of copyrighted works, such as text, images, charts, tables, musical works, sound recordings, audiovisual works, in a live classroom Using copyrighted works in distance education: The TEACH Act • The law was revised by Technology, Education and Copyright Harmonization (TEACH) Act of November 2002 to allow for use of works through digital networks in distance learning. [Section 110 (2)] – Permits performance of nondramatic literary or musical works (excerpts from books, journal articles, songs, etc.) – Permits “reasonable and limited portions of any other work” (paintings, charts, graphs; dramatic: operas, plays; audiovisual works, etc.) – Permits display of work in amount comparable to typical live classroom session – If teaching done by instructor as integral class session as part of “systematic mediated instructional activities” – If use is directly related to teaching content – If transmission is limited to students enrolled in course The TEACH Act: Institutional requirements – Applies to government bodies and accredited nonprofit educational institutions – Copyright policies must be in place – Institution must provide informational materials to faculty, students, staff to promote compliance with copyright law – Copyright notices must be placed on materials – Technical security measures must be made to prevent retention “beyond duration” of class session and unauthorized further dissemination – Interference with technological protection measures is not permitted The TEACH Act • Also: – Permits retention of content and student access for limited time, provided that no further copies are made – Permits reproduction and retention as necessary for technical purposes – Permits digitization of analog works for classroom teaching if amount is appropriate and if digital version not already available at the institution or if it is available but restricted by technological protection measures [Section 112] Distance education: options • Take advantage of the TEACH Act – Involves cooperation among instructors, administration, and systems specialists – Requires compliance with all requirements—all or nothing • Take advantage of fair use – If you cannot comply with all terms of TEACH Act – If institution does not offer means for implementing terms of TEACH Act • See Checklist for the TEACH Act, in Kenneth D. Crews, Copyright Law for Librarians and Educators: Creative Strategies and Practical Solutions, 2d ed. (Chicago: American Library Association, 2006), 126. Using copyrighted works in teaching • Reasonable, limited, isolated, non-repeating uses of materials are more likely to be fair use • Limit to amount needed to meet educational purpose • Key factors are brevity, spontaneity, cumulative effect • Always credit the source • The risks associated with digital access need to be considered in the fair use analysis • Handouts should not be a substitute for class reading materials or coursepacks, or for “consumable” workbooks—avoid multiple copies of different works that substitute for the purchase of works Academic coursepacks • Basic Books, Inc. v. Kinko’s Graphics Corp., 758 F. Supp. 1522 (S.D.N.Y. 1991) Kinko’s copy shop photocopied copyrighted material from a book for an academic coursepack. Not a fair use. Not all educational uses qualify for fair use. This case changed the way that institutions deal with coursepacks. • Princeton Univ. v. Michigan Document Servs., 99 F.3d 1381 (6th Cir. 1996) Again, coursepack copying of copyrighted material. Not a fair use. • Permissions should be obtained for copyrighted material in coursepacks • Generally it is the instructor’s responsibility to obtain permissions • See Campus Policy on Copyright Clearance, http://www.cites.illinois.edu/edtech/development_aids/copyrigh t/campus_policy.html Print and electronic reserves • Many institutions base their library reserve practices on fair use • Read institutional policies carefully • See UIUC Library Practices for Electronic Reserves, http://www.library.uiuc.edu/administration/services/ policies/electro_reserve.html Fair use scenarios for teaching Scenario 6. An instructor would like to distribute to a class a handout containing lyrics from modern blues, jazz, and rock composers, taking a few lines from 25-30 songs. Scenario 7. An instructor would like to include song lyrics, recorded music, images, and film clips in a classroom presentation on contemporary music. Scenario 8. An instructor would like to compile a collection of articles on human rights to serve as a course guide for a class, and make it available on a website accessible only to students in the class. Some of the articles will come from the professor’s personal collection of books Fair use scenarios for teaching and journals, some will come from print library sources, and some from electronic journal databases accessed through the library. Scenario 9. An instructor would like to show in a classroom short segments of recent news and entertainment programs on the 2008 U.S. presidential election, to analyze media coverage. Fair use discussion Scenario 10. For a graduate level project on early childhood education, a group of students would like to compile and publish a children’s book on reading. It will include short excerpts from different books—ranging from contemporary works such as Harry Potter, to traditional folk tales, in some cases with the language adapted and simplified for early readers; and in some cases translated from other languages. They are not certain if they will find a publisher, and if not, they will self-publish the book on the Internet. • What are the fair use considerations? Do the students need to seek permission from the copyright holders of the original works? Steps in determining whether to seek permission to use a work • Does a license restrict use of the work? • Is the work copyrighted in the U.S. today? • Does the use correspond with one or more of the exclusive rights of copyright holders in U.S. law? • Is the planned activity covered by fair use, or by a library, educational or other limitation or exception in U.S. law? The need to seek permission is more likely if: • The use is commercial • The use is repeated • The work is being used in its entirety and it is substantial Obtaining copyright permissions 1. Identify copyright holder • • • • 2. 3. Use copyright notice as a starting point Copyright holder might be author/multiple authors, publisher, heir or assignee/multiple heirs or assignees For published works, try the publisher Use any entity associated with author to track copyright holder Contact copyright holder directly --or— contact a collective rights organization to negotiate permissions Draft permissions letter • Include as much information as possible on planned use (what, where, when, why, how, how much) Obtaining copyright permissions 4. Negotiate permissions agreement, possibly involving fee 5. Obtain signed permissions agreement Lack of response does not substitute for permission More on collective rights organizations: • • • • Copyright Clearance Center (CCC): http://www.copyright.com/ International Federation of Reproduction Rights Organizations (IFRRO): http://www.ifrro.org/show.aspx?pageid=home See University of Texas copyright website on Getting Permission: http://www.utsystem.edu/OGC/IntellectualProperty/ PERMISSN.HTM See Columbia University copyright website: http://www.copyright.columbia.edu/collective-licensing-agencies University copyright policies and guidelines • University General Rules—Article III on Intellectual Property, http://www.uillinois.edu/trustees/rules.cfm • Good Ethical Practice: A Handbook for Faculty and Staff at the University of Illinois http://www.ethics.uillinois.edu/resources/handbook.cfm • University of Illinois, Office of the Chief Information Officer, Copyright Information and Policies http://www.cio.illinois.edu/policies/copyright/index.html • University of Illinois, Copyright Compliance Statement, http://www.cio.illinois.edu/policies/copyright/ccs.pdf • Univ. of Illinois, Academic Staff Handbook, Chapters 5 and 6, http://www.ahr.uiuc.edu/ahrhandbook/default.htm • University of Illinois, Student Code, http://www.admin.uiuc.edu/policy/code/ University copyright policies and guidelines • University of Illinois, CITES EdTech, Copyright & Fair Use, http://www.cites.illinois.edu/edtech/development_aids/copyright/index.h tml • University of Illinois, Office of Technology Management, Faculty Services http://www.otm.uiuc.edu/faculty • University of Illinois, Office of Technology Management, A Student’s Guide to Copyrights and Fair Use, http://www.otm.illinois.edu/sites/otm132.otm.uiuc.edu/files/Students% 20Guide%20to%20Copyright%20Revised%20Final%20Dec%202008%20for% 20print.pdf • University of Illinois, University Library website on copyright, http://www.library.uiuc.edu/scholcomm/copyright.htm University copyright policies and guidelines • University of Illinois Library Practices for Electronic Reserves, http://www.library.uiuc.edu/administration/services/policies/electro_re serve.html • University of Illinois, Graduate College Thesis Office, Copyright Information and Resources, http://www.grad.uiuc.edu/thesis/copyright.htm • Copyright Memo of Richard Wheeler, Vice Provost and Dean, Graduate College, on Thesis Requirement for Copyright Permission from Others, January 16, 2008, http://www.grad.illinois.edu/thesis/CopyrightMemo.pdf • University of Illinois, Business and Financial Policies and Procedures, Section 19.8: Software Copyright Compliance, http://www.obfs.uillinois.edu/manual/central_p/sec19-8.html • University of Illinois, Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research, Policy on Software Piracy, http://research.illinois.edu/piracy.asp Thank you! Janice T. Pilch Associate Professor of Library Administration Head, Slavic and East European Acquisitions University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign E-mail: pilch@illinois.edu This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this License, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/us or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, CA 94105, USA.