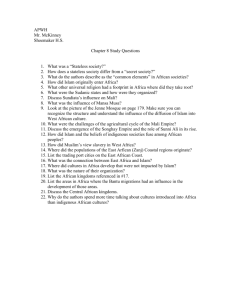

Landscapes, Sources, and Intellectual Projects in African History

advertisement

LANDSCAPES, SOURCES, AND INTELLECTUAL PROJECTS IN AFRICAN HISTORY SYMPOSIUM IN HONOUR OF PAULO FERNANDO DE MORAES FARIAS Programme 12-14 November 2015 department of African studies and anthropology centre of west African studies Photo courtesy of Anne Haour DRAFT Landscapes, Sources, and Intellectual Projects in African History Symposium in honour of Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias 12-14 November 2015 PROGRAMME FRIDAY 13 NOVEMBER 1. MYTH AND ARCHAEOLOGY Myth and Archaeology in Eastern Ethiopia. Timothy Insoll, University of Manchester The origins of ethnic identity and the settlements linked with different groups in eastern Ethiopia have been the focus of historical research but neglected by archaeologists. This is an omission of consequence for these are linked with myth and legend – be it Arab origins (Argobba) or great physical stature (Harla). Added to this are narratives centred on Islamic power and authority connected with jihad and focal figures such as Ahmad Gragn, “Ahmad the left handed” who used the city of Harar as a base to launch raids against the Christian empire in the first half of the 16 th century AD, as related in the Futuh alHabasha. Webs of fact and embellishment have been created and disentangling the two can be difficult. Archaeology offers a means to begin to rectify this. Beginning in 2014, excavations have been focused upon Harar and its wider region both to provide a settlement chronology and to evaluate the material culture ‘markers’ of cultural identity, trade, and Islamisation. This archaeological evidence is presented and the mythic and historical context re-evaluated based upon it. All that glitters is not gold: reconsidering the myths of ancient trade between North and subSaharan Africa Sonja Magnavita and Carlos Magnavita, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Berlin In this paper, the myth of a flourishing trans-Saharan trade in gold and slaves in classical Antiquity is questioned in the context of historical and archaeological research that continue to fail in providing positive evidence of such activities. Whilst gold and slaves, two of the main proposed commodities allegedly sought after in West Africa, remain largely invisible in the archaeological record, we emphasize that the integration of archaeometric methods can indeed help to trace them. As a prospect for current and future research targeting these topics, it is shown that the implementation of natural scientific methods may be helpful in disentangling fact from fiction by providing empirical evidence that is needed for reconstructing historical processes in a credible way. The 'Pays Do' and the Origins of the Empire of Mali Kevin MacDonald & Nikolas Gestrich, UCL Institute of Archaeology Research for this paper has been done in collaboration with Seydou Camara (ISH Bamako) and Daouda Keita (University of Bamako) In Autumn 2013, British and Malian archaeologists and historians worked together to document the past of ‘Do’ region of Tamani/Dugubani – notionally, a confederation of villages which formed one half of the nucleus of the Empire of Mali (c. AD 1230-1500). Heretofore, knowledge about the so-called three regions of 'Do' have been drawn from the great oral epics of Mali recited by griots hailing from the 'heartland of Mande' some 200km or more to the south-west. Indeed, on the basis of such accounts, the location of the ‘Do’ of Sogolon (mother of Sundiata) has been contested. This new work provides complex and interlinked oral accounts and archaeological data reinforcing arguments for a more easterly situation of the core and heartland of early imperial Mali (see also the 13 th-15th c. ‘power centre’ of Sorotomo, near Segou, excavated by this same team). The organisation of the heterarchical ‘Do’ polity, formed both for mutual defence and the coordination of ritual activities, will also be discussed. 2 DRAFT Archaeological survey documented a number of settlement mounds from different periods, including the notional capital of this early confederation: Dodugubani. However, another remarkable discovery was a massive 75ha tumulus field, with over 250 monumental tumuli, recorded at Teguébé, near the modern Malian town of Baroueli. Survey on the ground and by remote sensing has revealed the existence of hundreds, if not thousands of further tumuli in the region, on a scale heretofore unknown in this part of Africa. On the basis of surface ceramics, we provide an approximate temporal context for these sites. The potential implications of the Do region’s unique and extensive necropolis are also considered. 2. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BORDERLANDS: BENIN-BURKINA AND SAHARA-SAHEL Surveying the sand sea: research perspectives on Saharan medieval archaeology Sam Nixon, University of East Anglia During the medieval era the Sahara witnessed a revolutionary phase within its history, becoming a commercial gateway to West Africa, and experiencing the arrival and consolidation of Islam. Arabic historical documents provide a fruitful source to travel this historic landscape, tracking the trade routes which structured commercial life, the towns dotted along these, and the peoples who inhabited them. These sources have also provided a framework with which to approach and study the archaeological evidence of this medieval landscape, both epigraphy and settlement archaeology. Over the last 50 or so years archaeology has increasingly shown its potential to offer alternative sources of evidence to further our understanding of the medieval Sahara and its fringes, and a truly fruitful and fascinating scholarly interplay has developed between the study of historical documents and the study of the material remains found on the ground. This paper seeks firstly to provide an overview of this scholarly process, following this up with a consideration of the research directions which have been adopted in relation to medieval Saharan archaeology, and the future directions and outlooks for continuing research. Archaeological materials from Niyanpangu-bansu site and the contribution to understanding multi-ethnic populations on the right bank of the Middle Niger: the case of Borgu (North Benin, West Africa) B. Mardjoua, Student in MPhil / archeology at the Multidisciplinary Doctoral School of University of Abomey-Calavi, Benin Republic Niyanpangu-bansu, an abandoned settlement site, is located on the margins of the W National Park of Niger. The name of the site reflects its mixed heritage: ‘‘niyanpangu’’ means "new neighborhood" in the Gourmantche language and "bansu" "ruined habitat" in Baatonum. Oral and written sources both assign this site to the Gourmantche, one of the socio-cultural groups cited as the initial settlers of this of north Benin. Systematic archaeological survey conducted in 2012 and 2013 and test pitting carried out in March-April 2014 have generated substantial materials which, in combination with oral sources, contributes to a better understanding of the settlement history of the region. This paper will discuss the location and physical characteristics of the site, describe the methodology adopted and present the archaeological material collected and its contribution to the understanding of the multi-ethnic population the study area. Veiling and unveiling Loropeni mysteries Richard Kuba, Frobenius Institute The ruins of Loropeni in southern Burkina Faso and the other “Lobi ruins” have sparked curiosity and speculation since the early colonial period. Inscribed as UNESCO World Heritage site in 2009, these vast drystone walls reaching heights up to 6 meters and surrounding spaces larger than a football field were interpreted according to the different fashions of last century’s African historiography: From nonAfrican origins over slave trade transfer stations to entrepots of medieval gold trade and, more recently, as origins of the local Gan kingdom. This paper offers an overview of the rich production of historical mythmaking surrounding the “Lobi ruins” and, in the light of some recent archaeological evidences, tries to place the site within its regional and chronological context. 3. GRIOTS, TRADITIONALISTS, AND ORAL LITERATURE 3 DRAFT The Time-Tested Traditionist: Intellectual Trajectory and Mediation from the Early Empires to the Present Day Mamadou Diawara, Institut für Ethnologie, Goethe-Universität In the vast critical work that Paulo Fernando de Moraes Farias has devoted to the sources of African history, the author rightly presents the traditionist as a full-fledged intellectual in his own right. He thematizes the trajectory of this figure and deals with the spoken word and its relativity in an elegant manner. What does the body of the Griot, whether male or female, say and do that transcends the spoken words they pronounce so forcefully? What is this performance undertaken in order to make the text speak the meaning that it may or may not have? What still remains of the delicate balance between the text’s content and its staging, which is what bestows meaning upon the text? We will limit our scope to the Malian Empire (13th-19th centuries) and to the Jaara Kingdom (15th to 19th centuries). Three periods have marked this staging, indeed this performance. The first is the griot/jeli, examined first in the 14 th century, then in the 16th century, and finally in the present day. What is the meaning of this trajectory in a context that is now more than ever influenced by electronic media, and where the Griot, who is the media personality par excellence, is faced with the emergence of radio, television, cell phones and so many other forms of electronic communication? What does this mean for the intellectual project of these men and women? What remains of the text now that female Griots are taking center stage? The Next Generation: Young Griots' Quest for Authority Jan Jansen, Leiden University Scholars with an iconoclastic agenda have often criticised encyclopaedic informants, describing the narratives of these informants as either inventions or as texts co-authored by a researcher plus informant. Paulo Farias has explored a more nuanced approach in his analysis of Mali’s famous griots Wa Kamissoko and Tayiru Banbera. Farias sees these griots’ narratives as hybrid constructions that are motivated and inspired by twentieth-century issues, thus meeting and negotiating the demands of issues contemporary to the performance. This explains why such narratives are well received by a wide range of audiences. This approach challenges us to investigate how a griot reaches the level of credibility in which he can be trusted as an encyclopaedic informant by his contemporaries. Since answering this question based on the lives of much consulted griots would be a tautological and self-evident affair, this paper seeks to answer this question by analysing what young griots do when their prestigious and often consulted fathers die. It capitalizes on the experiences that the author (born in 1962) shared with his peers, while doing research on the “school of oral tradition” of Kela (Kangaba) in the period 1991present. Thoughts on a Nigerien oral literature piece: an overview of traditional and Islamic beliefs Ana Luiza de Oliveira e Silva, PhD student, Social History Program, University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil Our PhD research is focused on a six-volumes collection of West African oral literature. This piece is composed of sixty-seven stories and was conducted by Boubou Hama, the intellectual who published it in the 1970’s under the title Contes et légendes du Niger (Tales and Legends of Niger). Generally, we are interested in identifying which elements of traditional cultures of peoples such as Tuareg and Songhay were safeguarded by those stories. Since such narratives allow us to identify tracks of the magicalreligious universe of those peoples, we intend to, first, examine a few elements of their traditional beliefs. Secondly, we plan to reflect upon the process of penetration, reception and absorption of Islam in West Africa. Finally, we aim to focus on how elements of Islam and elements of traditional beliefs appear in a couple of tales and legends we study. With this paper, we intend to relate oral tradition (the stories) and worldviews (traditional and Islamic beliefs) in order to perceive what cultural aspects Boubou Hama rescued through those stories, having in mind the idea of propagation, recovery, and conservation of culture in post-independent West Africa. In praise of history; history in praise 4 DRAFT Karin Barber, University of Birmingham Paulo Farias has always treated historical sources, whether oral or written, not as reservoirs from which can be dredged certain hard historical facts concerning dates and events, but rather as the creation of thinking people formulating interpretations of their experience, including their experience of the past. The Arabic inscriptions of medieval Mali reveal, to an attentive reader, constructions of time and space; the oriki and itan of the royal bards of Oyo reveal not data about the reigns of the Alaafin but a perception of the role of historical memory itself. This approach, which I here honour by emulating, requires a close attention to form: to the conventions of the genres in which such interpretations are formulated. Yoruba praise poetry was described by one local intellectual, C.L. Adeoye, quoting Aristotle, as “truer than history”. The dynamics of praise poetry need to be grasped before one can make sense of this assertion. Oriki – precisely through their constitution as disjunctive, vocative, centreless and opaque flows of text – activate the potentials of past persons and powers by hailing their distinctive, idiosyncratic qualities. They evoke the “present in the past”. My question in this paper is what happens to this mode of apprehending the past when it is co-opted by literate local intellectuals, from the late nineteenth century onwards, into Yoruba print culture. Written history in the Yoruba language was everywhere – in newspaper serials, in pamphlets, in books published by local presses. Most of these texts made extensive use of oriki. In particular, I will look at Iwe Itan Ogbomoso (The History of Ogbomoso, 1934) by N.D. Oyerinde: a historian who could also be described as poet of past events. 4. SOKOTO AND THE CENTRAL SAHEL From Afnu to Copenhagen: Tripolitan diplomatic circulation, a Hausa slave, and knowledge of Africa in 1772 (draft) Camille Lefebvre, CNRS Paris In the 1740s-1750s, the two Nordic Kingdoms of Sweden and Denmark signed a series of treaties with Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli to support expanding trade relations across the Mediterranean. In this context, two consecutive delegations of Tripolitan diplomats were sent to the Nordic capitals to negotiate the treaties and to strengthen the relations between Tripoli and the Nordic Kingdoms. The encounter between the Tripolitan envoy Abderahman Aga and the German traveler Carsten Niebuhr in Copenhagen in 1772 led to a discussion of the interior of Africa as it was known at the time. The exchange between Abderahman Aga, his two African slaves, and Niebuhr yielded one of the few reports available in the second half of the Eighteenth Century on the Central Sudan. By focusing on the intellectual context of this encounter and the report that followed, this paper reassesses the contribution of this source to our knowledge of the Central Sudan in the late Eighteenth Century. Beyond Jihadist Pathos: Rediscovered Hausa Ajami Sources Reviewing the Sokoto Jihad Stephanie Zehnle, University of Kassel Generations of Sokoto scholars were engaged with the conservation and copying of the Jihadist triumvirate literature of Uthman and Abdullah dan Fodio, and Muhammad Bello. But in the 1880s, European colonial officials also collected texts from less popular local Hausa writers and brought them to Europe. One such scholar was Alhaji Umaru, or Al‐ Hajj Umar (1858‐ 1934). Born in Kano, he ended up as an Imam in Northern Ghana and wrote Hausa Ajami texts for – among others – the German trader and linguist Gottlob Adolf Krause (1850‐ 1938). While Umaru’s accounts deposited in Ghana (Legon) only describe the colonial conflicts in the 1880s, much of his historiographical material on the Sokoto Jihad among the Krause Collection was lost in the German Democratic Republic, where it could not be accessed from “Western” historians. Berlin State Library holds this collection today. This precious material reveals a counter narrative to the official and often pathetic Jihadist commemoration. Which Hausa oral traditions survived Jihadist censorship? And what do they tell about methods of Jihadist occupation? The proposed paper will explore a broad context of source production, transmission and (re)interpretation of Jihad history. It will compare the myths of the perpetrators to the myths of the victims. Taken alive, or dead in the Sokoto jihad? Murray Last, University College London 5 DRAFT At this time of remembering the 1st world war, and given Paulo’s interest in ancient gravestones, I thought we might discuss some of those never given such stones – casualties in the 19th century jihad. It is a feature of wars that far more are wounded than actually die in battle; and illness and hunger usually killed the most. But very few historians ever discuss mortality rates in wars within Africa. The most common assumption is that massive numbers of deaths were standard. My question to colleagues is: is there any way we can seriously work out casualty rates, or even military policy in warfare, within specific theatres of conflict? As one example, my very contentious suggestion is that the Sokoto jihad was perhaps not as lethal as many might imagine; and jihad may not be primarily about death. I shall try and offer some evidence for this, provocative though it might be. The Kano Chronicle Revisited Paul E. Lovejoy, York University, Canada One of the most important historical documents in the history of the Hausa states is what has become known as the Kano Chronicle, which is usually thought to be a compilation of oral traditions and perhaps also written texts that have been lost. As a history of the kings of Kano, it is usually thought that the Kano Chronicle was the product of many authors and traditionalists and not the work of a single individual. It is argued here, however, that the actual author of the Kano Chronicle that has survived was in fact a royal slave, Dan Rimi Barka, who was initially brought into the emir’s palace in Kano during the reign of Ibrahim Dabo (1819-1846) and subsequently continued in office under Dabo’s successors, dying in the late 1880s during the reign of Sarkin Kano Muhammad Bello (1883-1893). This chronology explains why the Chronicle ends abruptly with the reign of Emir Bello. Moreover, it is argued, subsequent additions to the Kano Chronicle were collected by C.L. Temple in 1909 and that these additions were the product of Dan Rimi Barka’s son, who was also a slave official in the palace of the emir of Kano, Muhammad Abbas (1903-1919). The emergence of the Ilorin Emirate and the perils of its historiography Stephan Reichmuth, Ruhr Universitat Bochum Ilorin emerged over a period of about thirty years as one of the successor states of the Old Oyo Empire and, at the same time, as an emirate within the Islamic realm of Sokoto/Gwandu, in a turbulent interplay of military and religious actors of diverse origins that remained highly enigmatic to contemporary observers. No wonder, then, that the historiography of this process still remains charged with tensions and contradictions. The paper reviews the sources and historiographical topoi which have prevailed in the description of the rise of Ilorin. Making use of some less known written sources and, at the same time, relying on oral and topographical material collected in Ilorin mainly during the late 1980s, it will attempt to open some new inroads into the thorny domain of a past that has continued to shape Ilorin society until the present. The problems of the unavoidable involvement of the latter-day field-working researcher in the local dynamics of identity formation will also be highlighted. 5. FOCUS ON SPECIFIC ARCHIVES AND COLLECTIONS What you see Daniela Moreau, Historian, Director of Acervo África, São Paulo, Brazil ACERVO ÁFRICA, São Paulo In 1906 the Dakar-based French photographer and picture editor Edmond Fortier (1862-1928) arrived at Timbuktu. He traversed West Africa diagonally in a SW-NE direction, departing from Conakry and then following the Niger River’s course from its source to the desert. Over five hundred photographs from this journey were published by Fortier in postcard format. The negatives have disappeared: printed on fragile pieces of paper, these images, which constitute a precious record of the region’s history, were scattered around the world. Inspired by Paulo Farias’ teachings and with his encouragement, I decided to assemble and study this wealth of material. The reconstitution of this visual corpus, which was fragmented and had not existed in effect, allowed me to bring to the fore precious information about a specific moment during the colonial period in the history of this vast region. In this paper, I intend to address the obstacles and challenges I faced while working with Fortier’s oeuvre, and to present the methodology employed to extract historical information from these early twentiethcentury postcards. To demonstrate the potential offered by this material as a research avenue for West African studies, I will analyse the sequence that portrays a Tuareg group, led by the amenokal Chebboun, at the French administrative Bureaux at Timbuktu. I will also show what are certainly the 6 DRAFT oldest photographs of Sanke mon collective fishing at San, and of the Kôrêdugaw rite at Ségou – both being cultural expressions from the Republic of Mali registered by UNESCO as world heritage, requiring permanent protection. To reflect upon the importance of precise sorting and dating of Fortier’s series, I will turn to the question of the photographer’s postcards purported influence in Picasso’s work. Materials and Mythology: Making History The Emil Torday Expedition to the Belgian Congo, 1907-1909 Rebekah Sheppard, PhD Candidate, Sainsbury Institute for Art, University of East Anglia The Emil Torday Expedition left for the Kasai in 1907 and spent two years in the former Belgian Congo (modern-day Democratic Republic of Congo). The expedition members were Emil Torday, Merville Hilton-Simpson and the artist, Norman Hardy. They collected over 3000 artefacts for the British Museum, as well as a further thousand or so for museums around the UK, Europe and the United States. They took photographs (numbering over 1500) and, most significantly, spent considerable time with the Nyimi (loosely translated as King, or Emperor) of the Bushong-Kuba, recording and transcribing oral histories. The wax cylinders that held these historical sound bites and music have disappeared from the archives, but what remains are material remnants of conversations and dialogue that are revealing of a political ideology on both sides of the exchange. The “encounter” was made up of performances; a corpus of interconnecting materials, objects, people and orality. This paper attempts to reinvigorate the active properties of artefacts (what they do, or did) within this encounter context. The reason for the inclusion of this contextual information is to re-invigorate the active and contemporaneous properties of historical texts and museum collections -especially their orality- that can be said to remain despite their supposedly external and distant authorship. These artefacts and performances mobilised history, and connected the material to the immaterial world in both Europe and Africa. Highlights from the West African Manuscript collection of the British Library Paul Naylor, PhD Student, DASA, University of Birmingham The latter half of the 19th century marked a proliferation of exchange in written manuscripts between the western and central Sudan. The works exchanged reflected the preoccupations of the time: a continued enthusiasm for the Sokoto Caliphate and purification of the faith by jiḥād coupled with an increasing Sufi spirituality, as well as a growing sense of unease at European presence in the region. A collaborative project with the British library has given me access to previously unstudied material originally held in private libraries in the Senegambia region. Drawing on the growing field of West African manuscript studies, I will demonstrate the breadth of material encountered in such libraries and unearth some of their treasures. As I am still going through the manuscripts, this is very much a work in progress. However, a letter from an irate scholar demanding the return of his book, a talisman for the safe return of a run-away wife, a diwān of pre-Islamic poetry and copied works of the Sokoto jihadists have been among the material encountered so far. This paper will place these manuscripts in the context of historical scholarship for this period although the main aim is to disseminate this material to a wider audience of West Africanists. 6. IDEOLOGICAL AND RELIGIOUS ENCOUNTERS Europe/Africa/America circuits to time and silenced Stories Elias Alfama Vaz Moniz, Pró-Reitor de Extensão na Universidade de Santiago, Ilha de Santiago - Cabo Verde The present study focuses on the processes that triggered the formation of the African Diaspora, at the dawn of modernity, defining a space of reference, in historical terms, the archipelago of Cape Verde, which, for a period of eighty-five years, received and fertilized seeds of modern African Diaspora, to be transformed into receptacle and factory for "domestication" of enslaved men and women, for further export to the Americas. This is a historical-cultural analysis of one of the most relevant issues for the understanding of modernity and relational processes between Africa, Europe and America, both in the framework of the meeting of peoples and cultures, from the mid-fifteenth century, and also in terms of the trajectory of Africa itself, in the context of political, social and cultural transformations in the period after the fifteenth century. In this context, what is at stake here is the possibility of launching other looks over relational processes triggered from the fifteenth century, based on historiographical traditions and epistemologies of differentiated knowledge, seeking to find the threads of a cross history of people from different backgrounds. 7 DRAFT Religious appropriation and rivalry: Ṣàngó and Islam in Ọ̀yó ̣ from the mid-18th to the early 20th century Insa Nolte, University of Birmingham This chapter explores the relationship between Islam and the Ọ̀yó ̣ deity of Ṣàngó from the 18th to the early 20th century, a period when the importance of Islam both in Ọ̀yó ̣ and its neighbouring polities increased steadily. Based on written and oral histories as well as other historical genres, the chapter emphasises the ambivalent political role of Ṣàngó, which reflected both an appropriation of Islam and its rivalry. The chapter discusses the role of Ṣàngó in Ọ̀yó ̣’s political organisation. From the 1770s, Ṣàngó provided divine legitimacy to Ọ̀yó ̣’s rulers and thus helped to consolidate their power after a period of political instability. Through political reform, Ṣàngó was closely linked to trade, the provision of justice, imperial control and military expansion. Closely associated with social and political fields increasingly linked to Islam in other parts of West Africa, Ṣàngó was indeed often identified as a Muslim, albeit a transgressive one. However, the deity’s appropriation of social and political fields associated with Islam also preempted the Islamisation of Ọ̀yó ̣’s political structures. Indeed, Ṣàngó continued to shape Ọ̀yó ̣’s political landscape even after the empire’s collapse. Apart from the rebel town of Ilorin, no Ọ̀yó ̣ town adopted Islamic political structures: instead, the growing number of Muslims organised along lines of the ‘traditional’ community. The chapter also explores the relationship between Ṣàngó and Islam in the practices of individuals and communities. In many Ọ̀yó ̣ towns, Ṣàngó was linked to the introduction of commodities and practices associated with Islam or the Muslim world, and sometimes even to the introduction of Islam as a ’client’ religion. In a productive engagement with Matory, one could even argue that the (political) gender relations mobilised by Ṣàngó were not completely different from those advocated by Islam. But as conversion to Islam became increasingly popular from the second half of the 19 th century onwards, the importance of private Ṣàngó worship declined. In this new context, the notion that Ṣàngó was a Muslim no longer provided an ambivalent form of legitimacy to Islam, but instead claimed such legitimacy for Ṣàngó. As Ṣàngó continued to occupy an important position in most towns’ political calendars, many Muslims accepted this claim. In conclusion, the chapter argues that the relationship between Islam and Ṣàngó remained deeply ambivalent throughout the period under discussion. Characterised both by the desire to benefit from the resources associated with Islam and to contain its potentially revolutionary impact, Ṣàngó allowed or even facilitated the spread of Islam as a private religion but prevented its transformation of Ọ̀yó ̣ structures of authority. SATURDAY 14 NOVEMBER 7. INQUISITION AND CHRISTIAN ENCOUNTERS IN PRECOLONIAL AFRICA Organiser: Filipa Ribeiro da Silva Chair/Discussant: Toby Green Panel Abstract In recent years, scholars working in the fields of African History and African Diaspora in the Americas and Europe have shown a great interest in the use of sources produced by the Inquisition, in particular, by the Iberian Courts. These materials proved to be of great value for studying African religious and belief systems, the creolisation of African practices transferred elsewhere or adopted by Europeans in the African and American continents, African politics and economies, and gender roles, among other topics. This new stream of research is producing an exciting body of scholarship which is simultaneously unveiling the potential of Inquisitorial sources for the study of African History and Diaspora and related subjects, the main methodological problems faced by researchers trying to study Africans at home or abroad or European contacts and interactions with African societies, cultures and religions using Inquisitorial sources and examine possible strategies to overcome these difficulties. Individual Abstracts Reconstructing African Voices from Inquisition Sources: Methodological Questions Filipa Ribeiro da Silva, University of Macau, SAR China The Iberian Inquisition Courts in Europe, the Americas and Asia produced an extensive body of primary sources, which have valuable data to reconstruct African Voices in Africa and in the Diaspora during the early modern period. In recent years, scholars working on African History and the study of African 8 DRAFT Diaspora in the Americas have started to explore these source materials to rebuilt material, religious and spiritual dimensions of African livelihood. Although these primary resources have a great potential for the study of African past and its legacies in Europe and the Americas, they also pose multiple challenges to the scholars. In this paper, I will examine the ways in which Inquisition sources were produced and discuss how the modes in which they were written raise serious problems to scholars interested in using them to reconstruct African trajectories. To do so, I will focus on the following main questions: i) how did the social standing of Africans influence the value given by these courts to their eye-witness accounts in cases against other Africans and Europeans; ii) how did the prejudice of Inquisition agents and European eyewitnesses shape the accusations made against Africans before these courts; iii) how did the personal interests of eye-witnesses (either political, economic or social weight on their accusations against Africans? iv) how did translators and clerks that mediated communication between Inquisitors and the Africans unable to speak European languages influence the recording of the accounts we have at our disposal today? v) how did the lack of knowledge of eye-witnesses, Inquisition agents and Inquisitors about African cultural practices and belief systems informed or misinformed their accounts, their writings and their understanding of African realities? vi) how did the views of the Inquisitors and the Inquisition agents on Africans influence the outcome of the court-cases against Africans? Our analysis will be based on a wide selection of source materials from the Inquisition Court of Lisbon portraying African either as targets of the Inquisition or as witnesses against other fellow Africans or Europeans, based in Africa, the Americas or Europe. Religious Instruments, Instrumentalism, and Belief: the challenges of reconstructing colonial religious history using Inquisition records Joanna K. Elrick, Vanderbilt University, USA The definition of “belief” presents one of the greatest methodological dilemmas for investigators of religion. Historians of African religion in the colonial period regularly confront this quandary. West African and West Central African religions are, in the majority of instances, transmitted from one generation to the next via oral instruction, initiation, and ritual demonstration. Further, individuals who stood accused of engaging in African religious practices had overwhelming motivation to deny such beliefs and practices. Institutions tasked with the maintenance of the colonial order, such as the Inquisition, often had the power to imprison the accused parties indefinitely, seize their property, and sentence them to death. Thus, descriptions of religious objects and ritual actions in archival records provide much of the evidentiary basis for religious exchanges between Africans and Europeans. However, to what extent are these objects emblematic of actual belief on the part of the persons accused? Are present-day historians in a position to speculate about the internal belief structure of individuals who lived in the Early Modern period? This paper will analyze these challenges. Death in Inquisition Sources on Angola in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Kalle Kananoja, University of Helsinki, Finland Popular characterizations of Africa as a white man’s grave abound in literature about the continent. While scholarly studies of European migrants’ mortality prior to advances in tropical medicine in the late nineteenth century confirm this view, we know much less about precolonial Africans’ conceptualizations of death. There has also been very little discussion of early modern European settlers’ attempts to adapt to African disease environments. This paper seeks to fill these lacunae by discussing Portuguese and African views on death in Angola. It argues that interpretations of death not only generated conflicts but also connected people. The Inquisition sources discussed in this paper demonstrate that Portuguese and African views on death were not far apart but resembled each other to the extent that people found common ground in negotiating the proper ways to handle rituals connected to afterlife. Portuguese attempts to sanitise funeral practices had little effect until the end of the eighteenth century and African burial rituals continued to dominate Angolan religious life. The material aspects of the Christian education system in the Kongo Kingdom (16 th-18th century) Inge Brinkman, Ghent University By the end of the fifteenth century, the king of the Central African Kongo polity had converted to Christianity, and diplomatic relations were established between the Kongo kingdom and Southern Europe (later also with the Dutch). Under the Kongo king Afonso I – who ruled from 1509 to 1542 – a school system was introduced. Supervised by the Portuguese clergy – who were closely associated with the royal court – firstly 9 DRAFT youngsters in the kingdom’s capital were trained. These literate Kongo people were then sent out to all the provinces to establish schools for boys and girls separately, to teach the Christian faith, grammar, reading and writing. Ever more people in the kingdom came to know Latin, Italian, and especially Portuguese. In this paper I want to trace the history of this formal Christian educational system in a diachronic perspective up to the end of the eighteenth century, thereby focusing on its material aspects. Learning is obviously a mental process, and in this particular case, the educational system had clear religious and political implications. Yet, educational systems also always have a material component that has hitherto received little attention in history. The spatial lay-out of the buildings, the classroom design, the use of paper and books, the materials used for writing, etc. will all be discussed as far as the sources permit. 8. MALI, SONGHAY, AND THE WESTERN SAHEL Pour en finir avec la charte du Manden Francis Simonis, Université d'Aix-Marseille La charte du Manden, ou charte de Kurukan Fuga est sans cesse évoquée aujourd’hui comme un élément fondamental de l’Afrique soudanaise médiévale. Bien mieux, elle a été classée au patrimoine immatériel de l’humanité de l’Unesco en 2009. Elle semble cependant reposer sur des bases scientifiques très douteuses, au point qu’il est nécessaire aujourd’hui de se poser une question simple mais essentielle: et s’il ne s’était jamais rien passé à Kurukan Fuga? Subsidiarité et dialogue des sources: réflexions sur Mâli et Sijilmâsa à partir du cas d’étude du royaume songhay François-Xavier Fauvelle, TRACES, Toulouse, France L’opus magnum de Paulo F. de Moraes Farias, Arabic Inscriptions from the Republic of Mali (2003), est un chef-d’œuvre d’érudition, et restera longtemps, pour les africanistes, un modèle d’édition de sources. Au-delà de l’exceptionnel corpus documentaire qu’il offre aux chercheurs, ce livre résulte également d’un effort visant à réécrire l’histoire du royaume Songhay, situé le long de l’arc oriental de la Boucle du Niger. Une telle ambition n’est réalisable qu’au prix d’un authentique dialogue entre des sources qui appartiennent à des régimes documentaires différents, en l’occurrence l’épigraphie funéraire médiévale et les chroniques de Tombouctou du XVIIe siècle, les fouilles archéologiques et les sources arabes externes, les matériaux oraux songhay et berbères. Un tel dialogue, qui est l’idéal de la recherche africaniste sur les périodes historiques, n’a cependant rien d’évident. Comme le montre P.F. de Moraes Farias, il suppose d’abord d’avoir mesuré la valeur heuristique de chaque catégorie de sources, et de cesser de considérer certaines d’entre elles comme des données ancillaires parce qu’elles seraient strictement factuelles. L’ouvrage de P.F. de Moraes Farias constitue de ce point de vue un changement de paradigme important en histoire de l’Afrique. Ce changement de paradigme doit être appelé de nos vœux dans le dialogue souvent encore impossible entre archéologie et sources arabes. A partir des exemples de la capitale du Mâli médiéval (celle décrite par Ibn Battûta et al-Umarî) et de Sijilmâsa, deux sites liés au commerce transsaharien et à l’histoire de l’Afrique de l’Ouest, nous montrerons comment une démarche archéologique non assumée visant à « confirmer » ou « infirmer » les sources écrites a jusqu’à présent, dans les deux cas, produit des connaissances qui s’avèrent résolument fausses. Mais renoncer à la subsidiarité de l’archéologie par rapport au texte ne fait-il pas courir le risque d’avoir à constater leur incomparabilité? Rethinking the place of Timbuktu in the intellectual history of Muslim West Africa Bruce Hall, Duke University The Malian town of Timbuktu is widely understood as the epicenter of Muslim intellectual history in West Africa. The ever-expanding numbers of Arabic manuscripts which are claimed as extant in Timbuktu has only further cemented the idea of the town as the font of a late-medieval high intellectual culture which rivaled other famous Muslim intellectual centers in Morocco and Egypt. Among the most important lessons that P.F. de Moraes Farias has taught us in his writings is how to read our sources for pre-colonial West African history in more careful and critical ways. In this paper, I propose a critical 10 DRAFT reevaluation of the place of Timbuktu in the intellectual history of Muslim West Africa on the basis of an analysis of the extent to which scholarly production in Timbuktu was incorporated into other writings produced by Muslim scholars elsewhere in the West African region. For practical purposes, my paper will focus on a selection of jurisprudential texts produced across the region between the 16th and early 20th centuries. I will argue that the degree of the intertextuality in West African jurisprudential writing— in other words, how often West African writers cite other West African writers—is an indication of the influence, and the extent, of organic, interconnected reading communities historically. The evidence suggests Timbuktu, after its zenith in the 16th century, ceased to be an especially important site in the intellectual tradition which was centered in Mauritania. My paper will attempt to re-situate Timbuktu in the intellectual history of Muslim West Africa. New reinventions of the Sahel: Reflections on the tārikh genre in the Timbuktu historiographical production, 17th-20th centuries Mauro Nobili, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign One of the most important lessons that scholars of African history draw from Prof. Paulo de Moraes Farias' work is to critically approach the famous Timbuktu chronicles - tarikhs. These chronicle are often studied as simple records of raw information written down by tape-recorder-like scholars, supposedly lacking of any intellectual agency. Prof. Paulo de Moraes Farias' research has proven this assumption wrong and has underlined the politico-ideological purposes which frame the chronicles. An innovative study based on several manuscript copies of the so-called Tarikh al-fattash inscribes itself in this new scholarly trajectory. The current edition of the chronicle dating 1913 is a problematic work, insofar as it conflates - in the opinion of the presenter - a 17th century's untitled tarikh written by one Ibn al-Mukhtar and a work written in the 19th century by Nuh b. al-Tahir al-Fulani serving political purposes of his time. The latter, although based on Ibn al-Mukhtar's chronicle, is an apocryphal work ascribed to the 16th century scholar Mahmud Ka'ti and is the only work truly called Tarikh al-fattash. This paper analyzes how Nuh b. al-Tahir al-Fulani reworked Ibn al-Mukhtar's tarikh and explores the politicoideological motivations that underline this literary falsification. 9. FOCUS ON SPECIFIC TYPES OF SOURCES Facts and Fatwas: Assessing the Usefulness of Legal Sources for Saharan History. Ghislaine Lydon, University of California at Los Angeles Since the publication of the co-edited volume by Kristin Mann and Richard Roberts, The Law in Colonial Africa, historians have increasingly looked to legal sources for writing African history. Historians of the Middle East, North Africa and Mauritania have made great use of fatwa literature as windows into the past (Ould El-Bara, 1991; Wuld al-Sa‘ad, 2000; Powers, 2002). This paper examines a body of legal opinions written by Muslim jurists. It assesses the usefulness of fatwa literature as a historical source for writing Western African social, and economic and political history. I first describe the profession of the mufti or jurist responsible for the writing of legal opinions and the typical format of the legal documents before presenting an overview of the different topics they address. The second half of the paper focuses on the place of legal evidence in Islamic legal practice, the legal validity of fatwas and their political use. The overall position of this paper is that despite their very rich informational value, there are limits to the usefulness of fatwas, especially when the business of producing them is motivated by political interests. Sahelian book collectors into the twentieth century Shamil Jeppie, University of Cape Town In this paper I shall try to demonstrate what might be gained from investigations into how a book collection was constituted over time. The use of archives is central to the practices of the historian but detailed examination of the making of an archive (as collection, a network of collections, or even one work) deserves much more attention. The history of the archive in the Sahel presents us with many possibilities to read the making of collections over time. While this paper focuses on the activities of the early twentieth century collector in Timbuktu, Ahmad Bularaf, it goes back into earlier styles of 11 DRAFT collecting, to the time of Ahmad Baba (d.1627). One of the abiding myths about the history of Africa is the relative insignificance of the written word. However, there are large stores of written materials across the Sahel available for multiple uses by historians with various interests. The study of the making of collections is one such approach. What is achieved through this type of study is at once a contribution to intellectual history and to the history of objects. Prof de Moraes Farias’ work is a major and inspiring contribution to the study of the intellectual worlds of the Sahel. He has opened up a huge archive for us and my paper is a modest contribution inspired by his work to take the intellectuals of the Sahel seriously as “colleagues” from the past and not merely as inanimate sources about the past. The Secret Language of the Tuareg as a Source Anja Fischer, University of Vienna This paper examines the use of Tagenegat, which is a special type of speech among the Tuareg nomads in the Algerian desert. I do not focus on the language code in my paper, but rather on the social function of the speech. The use of Tagenegat is not restricted to specialized groups, unlike how the secret language Tenet is restricted to artisans among Tuareg. I will analyse the social context of Tagenegat. What does the secret language tells us about the society? Why did nomads in a very remote area develop a secret language at all? What is the function of this language in the past and present? Does the settlement of many Tuareg influence the maintenance of the speech? To summarize, the main issue of the paper is the analysis of the secret language as source of knowledge about the social life among Tuareg nomads. Dreamworlds: Cultural Narrative in Asante Visionary Experience Tom McCaskie, University of Birmingham I have known Paulo Farias for forty years, as friend, colleague and inspiration. His is a daring and supple intellect, an instrument for making unexpectedly illuminating connections across a range of ideas and perspectives. He and I have a mutual interest in inner selfhoods, the ways in which individuals construe their lives in dreams, visions, nightmares and (so-called) 'madness'. All such experiences are personal, but their frameworks, their cues, are cultural and historical, however distant these might appear to be from lived reality. This paper addresses and analyses matters of this kind among Asante people, and it is grounded in a rich fieldwork by others as well as myself. It is not a contribution to the barren impasse known as 'psychohistory', but rather an attempt to come to grips with the ways in which Asante culture and history shape, seep into and colour the dreamworlds authored by the inner selfhoods of Asante individuals. 10. ANALYSING AND REPRESENTING SAHARAN SOURCES AND SOCIETIES L'ash‘arisme d'al-Murâdî al-Hadramî Abdel Wedoud Ould Cheikh, Université de Lorraine Au tout début de sa carrière de chercheur, P. F. de Moraes Farias s'est livré à une enquête d'une remarquable érudition sur les débuts sahariens du mouvement almoravide (XI e siècle), recherche qui fut notamment à l'origine de son article : "The Almoravids. Some questions concerning the character of the movment during its periods of closest contact with the Western Sûdân" (Bulletin de l'IFAN, t. XXIX, serie B, n° 3-4, 1967, pp. 794-878). Plus de trente cinq ans avant la parution de son monumental Arabic Medieval Inscriptions from the Republic of Mali (2003), qui renouvelle complètement, comme l'on sait, l'approche de l'histoire médiévale ouest africaine issue des grandes chroniques de Tîmbuktu, P. F. de Moraes Farias avait déjà introduit les germes d'une lecture tout à fait nouvelle des phases initiales de l'aventure almoravide dans l'article que je viens de citer. Parmi les personnalités les plus emblématiques de la période initiale de l'histoire des Almoravides évoquées dans ledit article figure un théologien du nom d'al-Murâdî al-Hadramî (m. 489/1095-96) dont le profil incertain associe mythe et histoire, les traits d'un théologiens "rationalisant" adepte du kalâm et ceux d'un saint au parcours "souterrain" miraculeux (sa "tombe" est réputée avoir été "découverte" six siècles après sa mort par un homme qui se disait "habité" par son œuvre...). Alors que les Almoravides passent pour avoir été plutôt hostiles au kalâm et à l'ash‘arisme, voilà que les œuvres connues de l'une de leurs principales figures au Sahara, al-Murâdî al-Hadramî précisément, manifeste clairement son adhésion à cette école théologique musulmane. J'aimerais, dans la communication que je propose, revenir sur ce personnage d'al-Murâdî à partir notamment d'une "profession de foi" qui lui est attribuée et qui a été récemment publiée au Maroc (‘Aqîdat Abî Bakr al-Murâdî al-Hadramî, Rabat, Dâr al-Amân li-l-Nashr wa-l-Tawzî‘, 2012). 12 DRAFT Les inconnus de l’époque moderne dans l’Ouest saharien : interrogations autour de l’implantation territoriale des Wlād Dlεym. Benjamin Acloque, EHESS – LAS Dans l’état actuel de rareté des sources, l’Histoire du Sahara à l’ouest de Tombouctou en est réduite à des suppositions. L’historiographie coloniale, et au-delà, a comblé les lacunes en se fiant aux récits postérieurs de groupes légitimant leur présence dans ces parages, ce qui correspondait à la vision figée, anhistorique, que les Européens pouvait se faire de la région. De nombreux indices donnent pourtant à penser des déplacements de populations et des rivalités religieuses. À partir de l’exemple la qabīla des Wlād Dlεym, considérée comme issue des Arabes Maˁqīl, on revisitera les évidences si fragiles qui fondent notre vision de l’Ouest saharien des XVI e et XVIIe siècles. Plutôt que de voir les Wlād Dlεym nomadisant très anciennement sur la côte, nous envisagerons leur déplacement depuis les environs du Twat vers l’Atlantique, à la faveur des bouleversements dans le commerce transsaharien consécutif aux effervescences religieuses au Twat comme à Tombouctou, et aux incursions des sultans de Marrakech au Sahara. 10,000 MSS, 1850 authors across 300 years: a preview of ALA-V Charles Stewart, Emeritus at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana and Visiting Scholar at the Institute for Islamic Thought in Africa, Northwestern University. In October Brill published the final geographic slice of the Arabic Literature of Africa series that was begun by Hunwick and O'Fahey 25 years ago. ALA volume 5 is, in fact, three volumes, encompassing the Hassaniyya-speaking world and Senegal Valley; it documents the legacy of fabled Sanhaja scholarship in Wadan, Tichitt, Walata and Timbuktu after those centers declined in the 17th century. Through it we learn about venerated teachers, intrepid travelers, occasional mujtahids, endless poets, breathtaking piety, enormous egos, advanced but rural education that Ibn Khaldun told us could not exist, and legal controversies triggered from abroad by such things as recitation styles, Salafi ideas and Wahhabi thinking. In light of ALA V, this paper speculates on the very limited parameters for manuscripts and authors yet to be discovered across the Sahel. It will survey what ALA-V tells us about the (remarkably similar) contents of Saharan libraries, texts studied and subjects favored, and, through an analysis of 2000 derivative works across 300 years of writing, we can sketch an outline of the intellectual history of the Sahara. All this adds up to much less than speculation about the millions of manuscripts waiting to be found in and around the Niger Bend, but much more than the adoration of select, colorful works under a simplistic, Timbuktu-centric vision of Islamic scholarship in the Sahel. Historical ‘demonizing’ of the Sahara and Contemporary Legacies: Mali in Crisis 2012-15 Ann McDougall, University of Alberta In this paper I address the question of ‘historical myths’ and how they distort our interpretation of African History, except that I want to go further and argue that they can and do actually shape that history. My case study is contemporary Mali. I draw on my previous publications about ways in which the Sahara was both constructed (literarily) to reflect European interests, fears and political interests (i.e. abolition of slavery), and simultaneously made to ‘disappear’ – to become the ‘Saharan void’ in which anything violent, cruel, deceitful, racist (antiwhite), Muslim (anti-Christian ) and exploitative (slave raiding, slave trading) can and will occur. I also noted that what had not been yet explored in the context of these processes was the role of ‘the Sahara’s sahelian neighbours’, to wit: “Their relationship with the desert that in most cases actually forms part of their respective contemporary nation- states, is an extremely ambiguous one. To whatever extent historical images of religious and social conflict (coalescing around jihads and slave trading/raiding) are ‘constructs’, the reality remembered in these countries tends to reflect and reinforce them. . . . No matter that those nineteenth-century jihads and subsequent reactions to colonial rule brought the whole region firmly into the Muslim fold and that intellectually as well as through ‘familial’ networks, the desert and its sahelian margins are a societal unity – the images of the past are what are used to further the social and political goals of contemporary sedentary governments.”1 Ann McDougall, “Constructing Emptiness: Islam, Violence and Terror in the Historical Making of the Sahara” in Idem (Guest Ed.), The War on Terror in the Sahara, special issue Journal of Contemporary African Studies 25:1 (2007). 1 13 DRAFT I will link analyses of the recent crisis to this historiographic paradigm, showing how it played out in Mali’s early history but most significantly, in the recent war that challenged the very existence of national existence. The crisis itself reflected the dual nature of Malian identity – ‘sub-Saharan, Saharan’ as well as its differing understandings of ‘being Muslim’ -- once again, the Saharan ‘terrorist’ version as opposed to the sub-Saharan ‘moderate’ view. But the fuel to flames within Mali itself also drew largely on the legacies of slavery associated with the Sahara and Saharans. Mali’s present owes much to the myths and mysteries shrouding its Saharan past. 11. POLITICAL PROJECTS IN/AS SOURCES The “origins” of the Fante state: the problematic evidence of “tradition” Robin Law, University of Stirling The Fante state was already in existence when detailed contemporary documentation of the area begins, in the early 17th century, so that our perception of its origins and earlier history are primarily dependent on local oral traditions. However, such traditions are inherently problematic, since they evidently reflect views about political ideology and practice in recent times, as well as (and perhaps more than) the period to which they purportedly refer. Moreover, given the early establishment of literacy in this particular area, the content of local “traditions” has been compromised by “feedback” from published European sources. This paper will attempt to interpret and evaluate the stories told about the origins of the Fante polity, with particular reference to the supposed migration of its founders from the interior, and to accounts of the establishment of a central political authority. Negotiating European presences in West-Africa in text: contemporary African historiographical responses to the reality and discourse of colonialism Michel Doortmont, University of Groningen and African Studies Centre Leiden This paper reviews the ways in which African intellectuals and activists reacted to the onslaught of European colonialism in the 19th century, by way of local and national histories, as well as culturalhistorical texts. Over the past decades, many African historical texts and oral sources have become available through (critical) academic and other publications. This offers the opportunity to ask structured - and more generalised - questions about the nature of these texts and oral sources in relation to the discourse of colonialism. Issues addressed in this paper will include the ways in which literacy influenced the way in which African historical texts were presented, the intellectual revolution literacy brought about, including the possibilities it offered to respond to colonialism, and the formation of new African historigraphical traditions in the process. Political and Historical Projects: Elite Slaves in Ilorin, Nigeria Ann O’Hear, independent scholar This paper investigates projects related to the history of slavery in Ilorin, a Muslim city and emirate in the western Middle Belt, very largely populated by Yoruba speakers. It examines sources pertaining to and produced by one specific group, the “elite” slaves of Ilorin and their descendants. Many of them were owned by the emirs, and they occupied important positions in the nineteenth century, enjoying influence, wealth, and prestige. Under British rule, some of them continued to exercise influence, for example, as baba kekere, controlling access to the emir. Thus, their project of self-aggrandisement was furthered by their position as emirs’ slaves. However, after a massive loss of influence in the 1930s, their status became an embarrassment rather than an opportunity. Thus, their project changed, becoming a historical one: the production of histories in which they strove to highlight their previous importance (and the ceremonial remnants of this), while hiding or glossing over their former slave status. The paper uses a variety of sources, including interviews and local publications, to explore these changing projects. Ablͻɖe Safui (the Key to Freedom): writing the new nation in a West African border town Kate Skinner, DASA, University of Birmingham Scholars have long valued African-owned newspapers as sources for reconstructing C19 and C20 political and social histories. The most studied newspapers are those produced in the major cities, written in English or French, and preserved in national archives. By contrast, African-language newspapers, particularly those that were produced in rural areas, are often patchily preserved or difficult to translate. Ablͻɖe Safui is the only privately-owned Ewe-language publication which was sustained over a 20 year period, spanning decolonisation and the emergence of single-party authoritarian regimes in the new 14 DRAFT nation-states of Ghana and Togo. Evident within its pages are debates among rural Africans about the purpose of the state, the nature of Pan-African relationships and the impact of the Cold War, but whilst Ablͻɖe Safui is clearly a rare and valuable historical source, it is inadequate simply to mine its pages for data or to treat it unproblematically as a 'voice from below'. Given the ephemeral nature of many other African-language publications, we need to explain how and why this newspaper was produced, distributed and consumed over an extended period. In this paper I consider Ablͻɖe Safui as a personal project, doggedly pursued by a single owner-editor in a bid to establish his legitimacy as a spokesman for the many people who experience political independence as a disappointment. Hermeneutics of Amharic literature: a philosophical reading. Sara Marzagora, PhD candidate, SOAS, University of London For decades, Amharic literature has been interpreted in a teleological way (Kane 1975, Fikre 1985). The early works of the first half of the 20th century were not considered novels but merely ‘creative writings’ because their moralistic, allegorical structure. From the 1950s-1960s onwards, so the critical reading goes, the first accomplished novels were finally produced, in fully-fledged realist style. But when moving beyond aesthetic considerations and taking into account the social context in which these literary works were produced, it becomes clear that the didacticism, moral polarization and allegorical elements of Amharic literature were far from being the product of a lack of literary skills. They were rather in line with the philosophy of learning prevalent in Ethiopia at the time. Most Ethiopian fiction writers were also influential ideologues, and their literary works are imbued with their political ideas. Literature was often used as a fictional exemplification of wider socio-political arguments over the management of the Ethiopian state. In this context, moral didacticism becomes an element of strength, not of weakness. These literary works have never been employed before as historical sources – yet they prove invaluable to reconstruct the intellectual debates going on in Ethiopia at the time. Amharic literary history is indeed intrinsically intertwined with the development of Ethiopian political philosophy. To the question, “where can one find African philosophy?”, this paper, in line with Alena Rettova and Kai Kresse, answers that literature can certainly prove one of the major hosts of African philosophy. 12. CLOSING SESSION With Karin Barber, Graham Furniss, and others TBC 15