File

advertisement

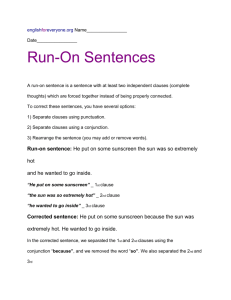

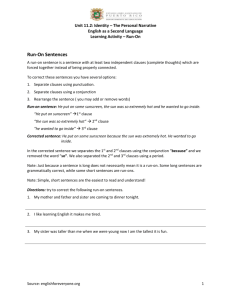

Editing Your work Creative Writing Troubleshooting Next Overused phrases – please avoid The word “suddenly” should be used no more than once. More than one adverb (“ly” words) in a sentence The phrases “soon after” or “just then.” (or similar) The phrase “It was then that…” Also avoid an ending where the protagonist dies (if possible). Especially avoid this if you have written your story in 1st person perspective, and/or in present tense. Next Troubleshooting Your Errors Click on the error to find out how you can fix it. Passive Sentences Run-on sentences Incomplete sentences Tense errors Giving context/background information Incongruous imagery Narrative inaccuracies/inconsistencies Wrongly punctuated dialogue Back Passive Sentences A passive sentence is one in which the true object of an action is made into the grammatical subject of the sentence. For example: In “Steve wrote the letter,” the action is writing.The person doing it, Steve, is the subject of the sentence. Now consider the same sentence slightly tweaked:“The letter was written by Steve.” Here, the main action is still writing, but the grammatical subject of the sentence is not the doer, but the do-ee — the letter. Passive structure can suck the life out of a sentence faster than you can say “bo-ring. “John hit him” has more of a pulse than “He was hit by John.” But sometimes you want to keep John out of it. And in those cases, a writer is fully justified in writing “He was hit.” What do you do about Passive Sentences? If you want the action to be direct and immediate, change passive sentences to active sentences. If you want to keep the person who is doing the action out of the sentence, you can use passive sentences – but use them with care as too many passive sentences makes your work difficult to read. “The dragon hit me from behind” sounds better than “I was hit from behind by the dragon.” Unless you don’t know it’s a dragon, in which case you can say,“I was hit from behind.” Back Run-On Sentences (R/O) A RUN-ON SENTENCE has at least two parts, either one of which can stand by itself (in other words, two independent clauses), but the two parts have been smooshed together instead of being properly connected. It is important to realize that the length of a sentence really has nothing to do with whether a sentence is a run-on or not; being a run-on is a structural flaw that can plague even a very short sentence. There are two types of run-on sentences. The first occurs when two main clauses are joined by a comma only. This is called a 'comma splice'. e.g. I picked up speed, I never felt so alive. The second type of run-on sentence occurs when two main clauses have no punctuation separating them. E.g I picked up speed I never felt so alive. What do you do to fix a run-on sentence? You can correct a run-on sentence in several ways. The method you choose in correcting your writing will depend on the relationship you want to convey between the two clauses (do you want to link them together? Or do you want them to stand on their own?). One method is to add end punctuation between the clauses and make two sentences. I picked up speed. I never felt so alive. Another way is to separate the clauses with both a comma and a coordinating conjunction. I picked up speed and I had never felt so alive. Back Incomplete Sentences (IS) An incomplete sentence is any word or group of words that creates the subject of a sentence, but fails to show the action taken by the subject. In an incomplete sentence, the underlined part of this example would be missing: The soldier took careful aim. How do you fix an incomplete sentence? Writers must understand that for every single, complete, individual image they put on paper, they must also put some corresponding action. The only way to fix an incomplete sentence, then, is to add a corresponding action to the alreadyexisting subject. Back Tense Errors (T) Verb tense refers to when the action is taking place in reference to the person telling the story. In creative writing, you will generally use either past tense or present tense. When there is a tense error, denoted by a capital T in the margin, it means that you have switched from different verb tenses. It is important to stay consistent. If you are writing in present tense, that means the action has a sense of immediacy, but you cannot predict what will happen next. If you write in past tense, everything is happening in the memory of the narrator (this means that if it is written in 1st person narrative voice, the narrator can’t die at the end). Click here for more information on verb tense. Correcting tense errors E.g. I am running late for class again. As I rush through the door, my teacher told me off. Correction – either present tense: I am running late for class again. As I rush through the door, my teacher tells me off. Or past tense: I was running late for class again. As I rushed through the door, my teacher told me off. Back Context and Background In creative writing it is sometimes necessary to give a bit of background information to the reader to help them understand the events that are unfolding. It is important, however, not to become bogged down in retelling detail – this is boring.You need to be able to inform or allude to important ideas in a few words. If someone reads your writing for the first time and puts a question mark in the margin, this means there is something you need to explain. How do you create a context? You need to know what information is necessary for the reader to understand the action. Instead of telling the reader what that information is, you must reveal it – but do it earlier rather than later. John gasped. The R573 had escaped and he knew that it would come for him first. In this example, the reader could be confused because they do not know what an R573 is or who John is and why the R573 would come for him first. Back This solution is too long and gets a bit boring: John was a big game hunter who had captured the R573, which is a robotic prototype of a sabre-tooth tiger.The prototype had gone a bit haywire and had run away after short circuiting. He handed it over to authorities, but not before having a run-in with its inventor, a deluded villain named Hans who swore he would kill John. Someone saw Hans reprogramming R573 and realised that he meant for it to kill John. Or we could try this solution: The R573 had escaped its enclosure. John was afraid. Although he had captured the robotic sabre-tooth tiger prototype once before, he wasn’t sure he could outwit it this time. Hans had repaired it, and remembering the villainous inventor’s threats, John was sure the tiger was coming for him first. Incongruous Imagery Incongruous imagery is figurative language that does not match the overall mood that you are trying to convey. Sometimes incongruous imagery occurs when you have used a cliché or overused phrase. Sometimes it happens when you use a word you found in a thesaurus without truly understanding all its connotations. E.g. She was afraid for her life. Her heart beat like a salsa dancer on the dancefloor. What to do about it Decide what the mood is you are trying to convey and think of images/colours/sounds that come to mind when you think of this mood. Back Narrative Inaccuracies Narrative inaccuracies occur when you have written about something that is incorrect or just doesn’t sound plausible (even taking into account the special circumstances surround genre fiction). Usually this occurs when you are writing about a topic you don’t know much about. Narrative inaccuracies can be tidied up with some tweaking and in fantasy fiction can sometimes be easily explained away using “magic” (e.g. “The tiny child put the armour on. It was magically lighter than it looked.” But NOT: “The newborn baby looked at its mother and cried, ‘Oh dear, I think I’ve come to the wrong place. Terribly sorry for the inconvenience, but I really did mean to be born in THAT manger over there.’”) Narrative inconsistencies occur when you contradict yourself somewhere in the story. These can be corrected if you carefully proof read things. (e.g. “She climbed the stairs in darkness black as pitch. The only light was that of her lamp.” ) Back Dialogue Nothing marks a beginning writer faster than improperly punctuated dialogue. Learn these rules, and you'll avoid obvious mistakes. Use a comma between the dialogue and the tag line (the words used to identify the speaker: "he said/she said") "I would like to go to the beach this weekend," she told him as they left the apartment. Full stops and commas go inside the quotation marks; other punctuation -- semicolons, question marks, dashes, and exclamation points -- goes outside unless it directly relates to the material within the quotes, as in this example from Raymond Carver's "Where I'm Calling From“. "I don't want any stupid cake," says the guy who goes to Europe and the Middle East. "Where's the champagne?" he says, and laughs. In general, don't use double punctuation marks, but go with the stronger punctuation. (Question marks and exclamation points are stronger than commas and periods. Think of it as a game of Rock, Paper, Scissors, if it helps.) When a tag line interrupts a sentence, it should be set off by commas. Note that the first letter of the second half of the sentence is in lower case, as in this example from Flannery O'Connor's "Greenleaf“. "That is," Wesley said, "that neither you nor me is her boy..." To signal a quotation within a quotation, use single quotes. "Have you read 'Hills LikeWhite Elephants' yet?" he asked her. For interior dialogue (i.e. thoughts not speech), italics are appropriate, just be consistent. If a quotation spills out over more than one paragraph, don't use end quotes at the close of the first paragraph. Use them only when a character is done speaking. When one or more person is conversing, each person contribution to the conversation should appear on a new line. “Where are you going?” Carol asked. “Mind your own business,” Karen replied, rudely. Back