Fallacies of Argument

advertisement

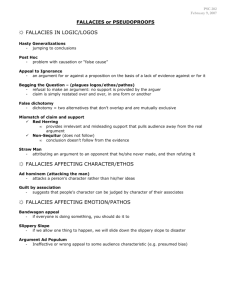

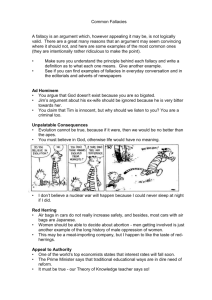

Fallacies of Argument AP Language and Composition Mr. Eble What are Fallacies? • Argumentative strategies that are…fallacious. • Errors in reasoning that render an argument invalid. • An “argument” in which the premises given for the conclusion do not provided the needed degree of support. • Fallacies deal largely with ethics, I.E. fairness, accuracy, and principles. • Avoid them in your own writing and challenge them in arguments you hear or read. Some General Guidelines for Avoiding Fallacies in Writing • Don’t Claim Too Much: Don’t expect to solve every aspect of an argument. Keep it simple, keep it safe. Some General Guidelines for Avoiding Fallacies in Writing • Don’t Oversimplify Complex Issues: Don’t reduce the argument to simplistic terms and come up with an easy solution, or you will lose your credibility and diminish your ethos. “George W. Bush wants money for the oil industry, so that’s why he’s starting war in Iraq.” “President Obama is a socialist Muslim, so that’s why he’s passing the health care bill.” Some General Guidelines for Avoiding Fallacies in Writing • Don’t Focus on Superfluous Issues / Elements: Because of the complexity of many issues, there are many facets; thus, don’t lose your focus on your topic in the wide sea of controversies. Example: Nixon’s Checkers Speech Some General Guidelines for Avoiding Fallacies in Writing • Support Your Arguments with Concrete Evidence: Don’t use abstract generalizations and familiar sentiments. Always assume that your audience is skeptical, expecting you to demonstrate your case reasonably, without bias or shallow development. Three Categories of Fallacies • Fallacies of Pathos • Fallacies of Ethos • Fallacies of Logos Fallacies of Pathos • Emotional arguments can be powerful and suitable in many circumstances, but writers can tip the scales of logic with overly sentimental responses. • These diminish trust. Fallacies of Pathos Ad Baculum: “Scare Tactics” Making an argument by scaring people and exaggerating possible dangers well beyond their statistical likelihood. Creating fear in people does not constitute legitimate evidence for a claim, and is therefore fallacious. This is remarkably common in advertising—political and otherwise. Such ploys work because it’s usually easier to imagine something terrible happening than appreciating its statistical rarity. Scare tactics stampede legitimate fears into panic or prejudice. Example: The Current Gun Debate One Side: “If we don’t have guns in our homes, we’re putting our families at risk of dying when a man enters our home to kill us—which could happen at any time.” Another: “We should outlaw guns because Fallacies of Pathos False Dilemma, or “Either/or” Either—Or arguments reduce complex issues to black and white choices. Most often issues will have a number of choices for resolution. Because writers who use the either-or argument are creating a problem that doesn’t really exist, we sometimes refer to this fallacy as a false dilemma. Example: "Either we go to Panama City for the whole week of Spring Break, or we don’t go anywhere at all." This rigid argument ignores the possibilities of spending part of the week in Panama City, spending the whole week somewhere else, or any other options. Example: “You either support the PATRIOT Act or you’re with the terrorists.” Example: “Either we cut spending or we'll increase the deficit.” (Have you heard of raising taxes?) Fallacies of Pathos Slippery Slope Slippery Slopes suggest that one step will inevitably lead to more, eventually negative steps. While sometimes the results may be negative, the slippery slope argues that the descent is inevitable and unalterable. Stirring up emotions against the downward slipping, this fallacy can be avoided by providing solid evidence of the eventuality rather than speculation. Example: "If we force public elementary school pupils to wear uniforms, eventually we will require middle school students to wear uniforms. If we require middle school students to wear uniforms, high school requirements aren’t far off. Eventually even college students who attend state-funded, public universities will be forced to wear uniforms.” Example: “The government wants to require background checks for pistols? Before we know it, it’ll take away our guns. What’s next—our freedom of speech? Our freedom of religion? Thus, we can’t let the government require a universal background check.” Fallacies of Pathos Ad Populum Appeals to popularity that hinge on the misconception that a widespread occurrence of something is assumed to make an idea true or right. Example: Politicians should enact gun control measures because recent polls tell us that many Americans want them. Example: “A Million Smokers Can’t be Wrong.” Well, yes they can. Smoking is unhealthy; many people making poor decisions doesn’t change that fact. Example: McDonald’s has served over 1 billion people, so it must be good, healthy food. Fallacies of Pathos Bandwagon Bandwagon Appeals try to get everyone on board. Writers who use this approach try to convince readers that everyone else believes something, so the reader should also. The fact that a lot of people believe it does not make it so. Some are obvious: “There are 25 people at this party and 20 are drinking, so you should, too!” Many are not. Many people are easily seduced by ideas endorsed by the mass media and popular culture; such issues include the War on Drugs, the War on Terror, health care reform, gun control, drunk driving, welfare reform, teen smoking, and illegal immigration— issues that make people feel that everyone should be concerned, that something—anything—must be done. Example: The McCarthy Communist Witch Hunts of the 1950’s Fallacies of Pathos Ad Misericordiam Argumentum ad Misericordiam (argument from pity or misery) the fallacy committed when pity or a related emotion such as sympathy or compassion is appealed to for the sake of getting a conclusion accepted. Examples “Oh, you spend $20 every day going out to eat? Well, you should be ashamed—that money could finance every student at Unifat School.” “Members of Congress can surely see in their hearts that they need to vote in favor of passage of the Gun Bill banning concealed weapons because their constituents who lobby for limiting firearms will be greatly saddened if they do not do so.” Fallacies of Ethos • Respect and trust are paramount in the reader/writer relationship. • Thus, writers should present themselves as honest, well-informed, or sympathetic in some way. • “Trust me” is a scary warrant, and not all attempts at gaining trust are admirable. Fallacies of Ethos Ad Hominem Ad Hominem (attacking the character of the opponent) arguments limit themselves not to the issues, but to the opposition itself. Writers who fall into this fallacy attempt to refute the claims of the opposition by bringing the opposition’s character into question. • These arguments ignore the issues and attack the people. • Example: Most political ads, specifically a recent one dealing with Ashley Judd’s possible campaign for one of Kentucky’s Senate seats. Fallacies of Ethos Tu Quoque (“You Also”) Tu Quoque (“You Also”) fallacies avoid the real argument by making similar charges against the opponent. Like ad hominem arguments, they do little to arrive at conflict resolution. "My position may be bad, but you should accept it because my opponent's position is just as bad." Example: "How can the police ticket me for speeding? I see cops speeding all the time.“ Example: “How can you give me a detention for not shaving, Mr. Eble? You have a beard!” Example: “Creationism is sometimes accused of being unscientific--of being merely a matter of faith, but the Theory of Evolution is also just based on faith." Fallacies of Ethos Poisoning the Well A specific kind of ad hominem, this sort of fallacy involves trying to discredit what a person might later claim by presenting unfavorable information (true or false) about the person in order to produce a biased result. A person committing this fallacy “poisons the well” by making his or her opponent appear in a bad light before he even has a chance to say anything. Example: President Obama is a Chicago politician, so don’t trust anything he tells you. Example: George W. Bush is a Texas oil man, so don’t expect him to do anything for the environment. Fallacies of Ethos Irrelevant Authority False Authority is a tactic used by many writers, especially in advertising. An authority in one field may know nothing of another field. Being knowledgeable in one area doesn’t constitute knowledge in other areas. Example: “Abortion is moral because the Supreme Court said so.” Example: “Mitt Romney is a businessman; President Obama is not. We need a president like Mitt who can run a business to run this country to get it back on track.” (Consider—Reagan didn’t have an MBA; GW Bush does). Fallacies of Ethos Dogmatism Asserting or assuming that a particular position is the only one acceptable. People who speak or write dogmatically imply that there are no arguments to be made: The truth is self-evident to those who “know better.” “No rational person would disagree that…” “It’s clear to anyone who has thought about it that…” When someone suggests that merely raising an issue for debate is somehow “unacceptable” or “inappropriate”—whether on grounds that it’s racist, sexist, unpatriotic, blasphemous, insensitive, or offensive in some other way—you should be suspicious. Example: “The truth, my friends, is found right here in this book — The Bible. All our answers are located between these leather covers, and no other truth exists. Any other belief is evil in the eyes of God.” Fallacies of Ethos Moral Equivalence Suggests that serious wrongdoings don’t differ in kind from minor offenses or vice versa: relatively innocuous activities or situations raised to the level of major crimes or catastrophes. Example: Paul Friedman obfuscates the line between banning abortion and other governmental actions, I.E. banning soda, advocating gun control, supporting early childhood education, and mitigating the effects of climate change Fallacies of Logos • You will encounter a fallacy in any argument when the claims, warrants, and/or evidence are invalid, insufficient, or disconnected. Fallacies of Logic Hasty Generalization Hasty Generalizations base an argument on insufficient evidence. Writers may draw conclusions too quickly, not considering the whole issue. They may look only at a small group as representative of the whole or may look only at a small piece of the issue. • Example: Concluding that all fraternities are party houses because you have seen three parties at one fraternity is a hasty generalization. The evidence is too limited to draw an adequate conclusion. • Example: I had an English teacher who assigned tons of work for no reason. All of them are such totalitarian punishment-mongers. Fallacies of Logic Begging the Question / Circular Logic Begging the Question (or circular logic) happens when the writer presents an arguable point as a fact that supports the argument. This error leads to an argument that goes around and around, with evidence making the same claim as the proposition. Because it is much easier to make a claim than to support it, many writers fall into this trap. Example: "These movies are popular because they make so much money. They make a lot of money because people like them. People like them because they are so popular." The argument continues around in the logical circle because the support assumes that the claim is true rather than proving its truth. Example: If such actions were not illegal, they would not be prohibited by law. Example: Belief in God is universal. After all, everyone believes in God. Fallacies of Logic Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc (after this, therefore also this) arguments, or post hoc for short, assume a faulty causal relationship. One event following another in time does not mean that the first event caused the later event. Writers must be able to prove that one event caused another event and did not simply follow in time. Because the cause is often in question in this fallacy, we sometimes call it a false cause fallacy. Example: On the Sean Hannity show, Representative Tom Cotton said, "The city of Chicago for instance has some of the most restrictive gun laws in the country. They also have some of the highest murder rates in the country.“ This doesn’t establish causality, as there could easily have been a third factor (or fourth…or fifth…). Also, this line of thinking establishes the claim that the more stringent gun control statues led to the increase in gun violence. Watch out for this fallacy with statistics… "Statistics are like bikinis: what they show is revealing, but what they hide is essential." Fallacies of Logic Equivocation Equivocation happens when the writer makes use of a word’s multiple meanings and changes the meanings in the middle of the argument without really telling the audience about the shift. Often when we use vague or ambiguous words like "right," "justice," or "experience," we aren’t sure ourselves what we mean. Be sure to know how you are using a word and stick with that meaning throughout your argument. If you need to change meanings for any reason, let your audience know of the change. Example: When representing himself in court, a defendant said "I have told the truth, and I have always heard that the truth would set me free." In this case, the arguer switches the meaning of truth. In the first instance, he refers to truth as an accurate representation of the events; in the second, he paraphrases a Biblical passage that refers to truth as a religious absolute. While the argument may be catchy and memorable, the double references fail to support his claim. Fallacies of Logic Non Sequitur Non Sequitur arguments don’t follow a logical sequence. The conclusion doesn’t logically follow the explanation. These fallacies can be found on both the sentence level and the level of the argument itself. Example: "The rain came down so hard that Jennifer actually called me." Rain and phone calls have nothing to do with one another. The force of the rain does not affect Jennifer’s decision to pick up the phone. Example: Perhaps every episode of Family Guy…especially this one. Fallacies of Logic Straw Man Attacking a straw man involves denigrating an argument that is much weaker or more extreme than the one the opponent is actually making. By “setting up a straw man,” the writer has an argument that’s easy to knock down and proceeds to do so, then claiming victory over the opponent—whose real argument was quite different. In other words, they choose to refute arguments that go beyond the claims their opponents have actually made. Example: “People who think abortion should be banned have no respect for the rights of women. They treat them as nothing but baby-making machines. That's wrong. Women must have the right to choose.” Example: “Those who support gun control are wrong; they believe that no one should has the right to defend themselves in any situation.” Fallacies of Logic Faulty / False Analogy Faulty Analogies lead to faulty conclusions. Writers often use similar situations to explain a relationship. Sometimes, though, these extended comparisons and metaphors attempt to relate ideas or situations that upon closer inspection aren’t really that similar. Be sure that the ideas you’re comparing are really related. Also remember that even though analogies can offer support and insight, they can’t prove anything. Example: Making people register their own guns is like the Nazis making the Jews register with their government. Example: Making the connection between the Nazis / Jews and Obamacare / Americans. Fallacies of Logic Red Herring Red Herrings have little relevance to the argument at hand. Desperate arguers often try to change the ground of the argument by changing the subject. The new subject may be related to the original argument, but does little to resolve it. Example: “Moeller should pave the lot next to school. Besides, I can never find a parking space at school anyway." The writer has changed the focus of the argument from paving to the scarcity of parking spaces, two ideas that may be related, but are not the same argument. Example: “You want to pass laws requiring background checks for guns? Well, criminals don’t follow laws as it is, so we shouldn’t bother passing these laws.”