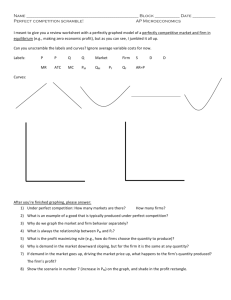

LECTURE #13: MICROECONOMICS CHAPTER 15

advertisement

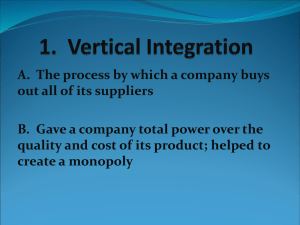

LECTURE #13: MICROECONOMICS CHAPTER 15 Monopolies Production and Pricing Decisions Public Policy 1 Why Monopolies Arise A. Competitive firms are price takers; a Monopoly firm is a price maker B. Monopoly: a firm that is the sole seller of a product without close substitutes C. The fundamental cause of monopoly is barriers to entry. 1. Monopoly Resources a. b. A monopoly can have sole ownership or control of a key resource used in the production of the good. A key example is DeBeers; it has at times controlled about 80% of the diamonds in the world. 2 Why Monopolies Arise 2. Government-Created Monopolies a. b. c. Monopolies can arise because the government grants one person or one firm the exclusive right to sell some good or service. Patents are issued by the government to give firms the exclusive right to produce a product for 20 years. Patents involve trade-offs; they restrict competition but encourage research and development. 3. Natural Monopolies a. b. Natural Monopoly: a monopoly that arises because a single firm can supply a good or service to an entire market at a smaller cost than could two or more firms. A natural monopoly occurs when there are economies of scale, implying that average total cost falls as the firm's scale becomes larger. 3 Why Monopolies Arise 4 Monopoly Production and Pricing Decisions A. Monopoly versus Competition 1. The key difference between a competitive firm and a monopoly is the monopoly's ability to influence the price of its output. 2. The demand curves faced by each of these types of firms are different as well. a. b. A competitive firm faces a perfectly elastic demand at the market price. The firm can sell all that it wants to at this price. A monopoly faces the market demand curve because it is the only seller in the market. If a monopoly wants to sell more output, it must lower the price of its product. 5 Monopoly Production and Pricing Decisions B. Monopoly's Revenue 2. A monopoly's marginal revenue will always be less than the price of the good (other than at the first unit sold). 1. 2. 3. If the monopolist sells one more unit, his total revenue (P x Q) will rise because Q is getting larger. This is called the output effect. If the monopolist sells one more unit, he must lower price. This means that his total revenue (P x Q) will fall because P is getting smaller. This is called the price effect. Note that, for a competitive firm, there is no price effect. 3. When graphing the firm's demand and marginal revenue curve, they always start at the same point (because P = MR for the first unit sold); for every other level of output, marginal revenue lies below the demand curve (because MR < P). 6 Monopoly Production and Pricing Decisions 7 Monopoly Production and Pricing Decisions C. Profit Maximization 1. The monopolist's profit-maximizing occurs where MR = MC. a. b. If MR > MC, profit can be increased by raising output. If MR < MC, profit can be increased by lowering output. 2. Even though MR = MC is the profit-maximizing rule for both competitive firms and monopolies, there is one important difference. a. b. In competitive firms, P = MR; at the profit-maximizing level of output, P = MC In a monopoly, P > MR; at the profit-maximizing level of output, P > MC 3. Monopolist's demand curve determines the price; how much buyers are willing to pay for the product. 8 Monopoly Production and Pricing Decisions 9 Monopoly Production and Pricing Decisions D. FYI: Why a Monopoly Does Not Have a Supply Curve 1. A supply curve tells us the quantity that a firm chooses to supply at any given price. 2. But a monopoly firm is a price maker; the firm sets the price at the same time it chooses the quantity to supply. 3. The market demand curve that tells us how much the monopolist will supply because the shape of the demand curve determines the shape of the marginal revenue curve (which in turn determines the profit-maximizing level of output). 10 Monopoly Production and Pricing Decisions A. A Monopoly's Profit 1. Monopolist’s profit: P = TR – TC. 2. Because TR = P x Q and TC = ATC x Q, we can rewrite this equation: Profit = (P – ATC) x Q. 11 Welfare Cost of Monopolies A. The Deadweight Loss 1. 2. 3. 4. The demand curve represents the value that buyers place on each additional unit of a good or service. The marginal-cost curve the added cost of producing each unit of a good. The socially efficient quantity of output is found where the demand curve and the marginal cost curve intersect. This is where total surplus is maximized. Because the monopolist sets marginal revenue equal to marginal cost to determine its output level, it will produce less than the socially efficient quantity of output. The price that a monopolist charges is also above marginal cost. Although some potential customers value the good at more than its marginal cost but less than the monopolist’s price, they do not purchase the good even though that is inefficient because total surplus is not maximized. 12 Welfare Cost of Monopolies The deadweight loss can be seen on the graph as the area between the demand and marginal cost curves for the units between the monopoly quantity and the efficient quantity. 13 Welfare Cost of Monopolies B. The Monopoly's Profit: A Social Cost? 1. Welfare in a market includes the welfare of both consumers and producers. 2. The transfer of surplus from consumers to producers is therefore not a social loss. 3. The deadweight loss from monopoly stems from the fact that monopolies produce less than the socially efficient level of output. 4. If the monopoly incurs costs to maintain (or create) its monopoly power, those costs would also be included in deadweight loss. 14 Price Discrimination A. B. Price Discrimination: the business practice of selling the same good at different prices to different customers The Analytics of Price Discrimination 1. 2. 3. Perfect price discrimination describes a situation where a monopolist knows exactly the willingness to pay of each customer and can charge each customer a different price. Without price discrimination, a firm produces an output level that is lower than the socially efficient level. If a firm perfectly price discriminates, each customer who values the good at more than its marginal cost will purchase the good and be charged his or her willingness to pay. a. b. There is no deadweight loss in this situation. Because consumers pay a price exactly equal to their willingness to pay, all surplus in this market will be producer surplus. 15 Price Discrimination 16 Public Policy toward Monopolies A. Increasing Competition with Antitrust Laws 1. Antitrust laws are a collection of statutes that give the government the authority to control markets and promote competition. a. b. The Sherman Antitrust (1890) lowers the market power of the large and powerful "trusts” that were viewed as dominating the economy at that time. The Clayton Act (1914) strengthened the government's ability to curb monopoly power and authorized private lawsuits. 2. Antitrust laws allow the government to prevent mergers and break up large, dominating companies. 3. Antitrust laws also impose costs on society. Some mergers may provide synergies, which occur when the costs of operations fall because of joint operations. 17 Public Policy toward Monopolies B. Regulation 1. 2. 3. Regulation is government's typical response in dealing with a natural monopoly. Most often, regulation involves government limits on the price of the product. It is possible that the government can eliminate monopoly deadweight loss by setting the monopolist's price equal to its marginal cost: However, this is often difficult to do. a. b. c. If the firm is a natural monopoly, its average total cost curve will be declining because of its economies of scale. When average total cost is falling, marginal cost must be lower than average total cost. Therefore, if the government sets price equal to marginal cost, the price will be below average total cost and the firm will earn a loss, causing the firm to eventually leave the market. 18 Public Policy toward Monopolies 4. Therefore, governments may choose to set the price of the monopolist's product equal to its average total cost. This gives the monopoly zero profit, but assures that it will remain in the market. a. b. There is still a deadweight loss in this situation because the level of output will be lower than the socially efficient level of output. Average-cost pricing provides no incentive for the monopolist to reduce costs. 19 Public Policy toward Monopolies C. Public Ownership 1. Rather run by a private firm, the government can run the monopoly itself. 2. However, economists generally prefer private ownership of natural monopolies. a. b. Private owners have an incentive to keep costs down to earn higher profits. If government bureaucrats do a bad job running a monopoly, the political system is the taxpayers’ only recourse. 3. Sometimes the costs of government regulation outweigh the benefits. 4. Therefore, some economists believe that it is best for the government to leave monopolies alone (do nothing) 20 21 Homework A. Questions for Review: 1, 2, 3, 6 (4th Ed: 1, 2, 3, 8) B. Problems and Applications: 1, 8 (4th Ed: 1, 9) 22