“Dreadlocks Be Your Savior”: A Rastafari Covenant and the

advertisement

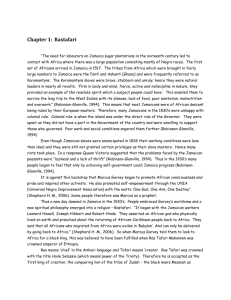

“DREADLOCKS BE YOUR SAVIOR”: A RASTAFARI COVENANT AND THE SUSTAINABILITY OF MEANING Benjamin Bean CSP 653: Topics and Issues in Cultural Sustainability: Identity March 30, 2014 Keep your culture Don't be afraid of the vulture Grow your dreadlock Don't be afraid of the wolf pack (Bob Marley & The Wailers, “Rastaman Live Up!”1) Perhaps the most widely known visual sign of Rastafari identity, the dreadlocks hairstyle has a complex and mysterious history, one which parallels that of the movement and its early cultural evolution. A symbol of African heritage, a rebellious statement against white colonial fashion norms, a covenant of ascetic commitment to Jah (God), a source of individual power and pride, a tribute to the martyrs of the black liberation struggle, and a marker of group solidarity, Rastafarians’ dreadlocks evoke many layers of meaning for members of the movement, along with mixed reactions and perceptions from others. Now a popular hairstyle among non-Rastas, and certainly not a universal feature of Rastafari followers, dreadlocks have become a subject of discussions about cultural appropriation, authenticity, and authority, taking on new significance as the style becomes popular in countries and subcultures far removed from Jamaica and its PanAfricanist revolutionaries. The commodification and conflicting experiences of this cultural symbol, while compromising its power of identification for Rastafarians, nonetheless seem to be inconsequential to its value as a bearer of heritage and an identity grounded in the past with a vision for the future. As a symbol of belonging – to a community of faith, to an idealized African nation, to humanity, and to the earth – dreadlocks tell a story of the Rastafari people: a story of alienation, struggle, and ultimate redemption. In my attempts to convey the significance of the dreadlocks in this essay, I submit that the most relevant voices, if not the most authoritative, are my Rastafarian interlocutors who have Bob Marley and the Wailers, “Rastaman Live Up!” Confrontation. LP. Tuff Gong Records, 205 482-320. 1983. 1 2 shared a diversity of cultural viewpoints over my last few years of fieldwork in the Greater Philadelphia Area, as well as a short study in Jamaica. However, a brief history of the movement is indispensable for understanding the social frameworks in which Rastafarians create meaning and articulate their collective and individual identities. In this context, I will explore the evolving significance of dreadlocks by synthesizing the ethnographic works of scholars such as Barry Chevannes, Jake Homiak, and Michael Barnett, whose immersion in the Rastafari communities of Jamaica has informed their many valuable insights on the movement and its cultural expressions. My experiences as a white, non-dreadlocked, non-Rastafarian musician in the Philadelphia reggae scene inform my perspective on locks as a cultural symbol that has been problematized within discourses of authenticity and group boundaries. As I consider the spread of dreadlocks as a hairstyle among non-Rastas, along with the shifting away from an obligatory wearing of dreadlocks as a covenant within the Rastafari movement, my aim is to call into question the efficacy of cultural symbols as sources of meaning, identity, and group cohesion. Racialized Resistance and the Emergence of Rastafari After the abolition of slavery in British-ruled Jamaica in 1834, the white minority continued to control land and resources throughout the island. Their power was preserved, in part, by importing cheap labor from Asia, Europe, and Africa, while black landowners struggled to build their own economy, communities, and education system that were independent of the British colonial system. The legacy of slave resistance in Jamaica, which consisted of more violent uprisings than any other emancipation effort in the Western hemisphere, persisted through the remainder of the colonial era, as black Jamaicans continued to fight for equality and independence, drawing much of their inspiration from anti-colonial struggles elsewhere in the African diaspora. Perhaps the most well known example of violent conflict in Jamaica’s post- 3 slavery era, the Morant Bay Rebellion of 1865, led by a black religious leader named Paul Bogle, highlighted an emerging concept of blackness around which many of Jamaica’s poor and oppressed citizens began to discover a sense of identity. While independence from the empire would not be achieved for nearly another century, the military might of Great Britain was insufficient against the solidarity that Jamaicans would find in their black skin and African roots.2 The desires for repatriation and formation of a strong Pan-African community were perhaps most articulately expressed and disseminated in the preaching and writings of Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican whose childhood experiences in the late 19th century had a profound influence on his identity as a black man. Especially as Garvey’s influence spread into North America with his establishment of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), many black Jamaicans began to revere the leader, who taught that, while people of different races are ultimately equal, black people should respond to white supremacy and colonial oppression by conceiving their religious and national identity “through the spectacles of Ethiopia.”3 While his promise of the Black Star Line, a fleet of ships that would return displaced Africans to their home continent, never came to fruition, due to his conflicts with the US government, Garvey nonetheless retained the respect of many in Jamaica’s poor black communities. Some of these of a statement Garvey made in the late 1920s, proclaiming that a leader would arise in Africa who would deliver the diaspora from its bondage in the west. In November of 1930, the coronation of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I was interpreted by some groups as the fulfillment of Garvey’s prophecy, and out of these groups emerged the first Rastafarians, professing that Selassie (whose 2 Horace Campbell, Rasta and Resistance (Trenton: Africa World Press, 1987), 35-40. Marcus Garvey, The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, ed. Amy Jacques-Garvey (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company,1925), 44. 3 4 pre-coronation title and name was Ras Tafari Mekonnen) was the second coming of Jesus Christ, returning to fulfill the prophecies in the book of Revelation and return Africans (the true Israelites in exile) to their Promised Land. The fact that Garvey himself never agreed with the Rastafarians on this point4 did not deter them from preaching this new faith in the streets of Kingston and its nearby rural communities. The first Rastafarian communities continued in the Garveyite tradition, awaiting their imminent repatriation while sustaining their communities through economic means independent of the white wealthy class. Although their early texts, such as The Royal Parchment Scroll of Black Supremacy, along with the rally cry of “Nyahbinghi!” (which means “Death to white oppressors!”), reveal a militant black separatism,5 there is very little evidence of any violence or racially motivated crime by Rastafarians in the early years of the movement. Even today, there are many Afrocentric emphases in Rastafari’s cultural expressions, and their rhetoric is full of fiery imagery – “Burn down Babylon!” is a common expression of their desire to see the oppressive powers of the world destroyed by the hand of Jah (God) – however, members of the movement are insistent on their adherence to pacifism and acceptance of all races, colors, and creeds. Now the interpretation of “Nyahbinghi!” is “Death to black and white downpressors; as one priest explained it to me, “That change a long time ago, man. With the realization that we have black downpressors as well, that had to change quick.”6 The lack of documentation from Rupert Lewis, “Marcus Garvey and the Early Rastafarians: Continuity and Discontinuity,” in Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader, ed. Nathanial Samuel Murrell, William David Spencer, and Adrian Anthony McFarlane (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998), 149. 5 William David Spencer, “The First Chant: Leonard Howell’s ‘The Promised Key,’” in Murrell, Spencer, and McFarlane, Chanting, 362. 6 Personal interview with anonymous Nyahbinghi priest in Jamaica, November 2010. The priest also rejects the use of the term “black supremacy,” which many Rastas embrace, although it is usually explained as something different from racial superiority. While he believes in the equality of the races, this priest also indicated his opinion that interracial marriage is wrong, a 4 5 the early years of the Rastafari leaves the evolution of racial thought within the movement open to speculation; however, it is clear that the longing for an idealized Africa – commonly referred to as the biblical Zion – has always been central to the Rastafari faith. Evolution of the Rastafari Movement Writing in the early 1990s, Jamaican anthropologist Barry Chevannes outlined the history of Rastafari by dividing it into three twenty-year periods.7 During the first two decades, the primary focus was a fundamentally Christian one, albeit in stark contrast to the mainstream church institutions, which many perceived to be representative of white, colonial religion. The main difference, of course, was the assertion that the book of Revelation had been fulfilled: the black Christ – not the white god of the slaveholders’ indoctrination – had arrived in his kingly character to return his people to their homeland. Hopeful that this repatriation would occur quickly, several of the first Rastafarians began preaching this message in the streets, occasionally complementing their Biblical references with lines from an article in the June 1931 issue of National Geographic, which recounts with great detail and color photographs the well attended coronation of Selassie in the previous November.8 The adherents of this new faith used the hymnals of their Christian churches in their earliest worship services, adapting the lyrics to fit their teachings: for example, substituting “Jesus” with “Selassie” and “Rastafari.” Many Rastafarians gathered to live in communes while awaiting their repatriation, and at least one such complicated set of ideas that mirrors Garvey’s teachings. The apparent contradictions and complexities within Rastafarian racial philosophy reflect both the movement’s historical underpinnings and its present negotiation of identity as the faith and culture continue to spread around the world. 7 Barry Chevannes, “Rastafari and the Exorcism of the Ideology of Racism and Classism in Jamaica,” in Murrell, Spencer, and McFarlane, Chanting, 59-60. 8 Personal communication with Jake Homiak, 2010. When I visited the Discovering Rastafari! exhibit at the National Museum of Natural History in 2010, Homiak (the curator) pointed out this issue of National Geographic on display, explaining how it was instrumental for early Rastafarians in developing their theology and interpretations of biblical prophecy. 6 commune, under the leadership of Leonard Howell, supported itself by growing and selling ganja (marijuana), which had become popular in Jamaica with the arrival of laborers from India in the mid-19th century.9 As ganja had been made illegal several years prior to the emergence of Rastafari, the authorities raided Howell’s camp on multiple occasions, beginning what would be a long, troubled relationship between Rastafarians and law enforcement. This conflict not only resulted in the Rastas’ regard for marijuana as a “holy herb;” it also offered members of this new faith another reason to view themselves as God’s chosen people, persecuted in the twentieth century as their Israelite ancestors were in Egypt, Babylon, and the Roman Empire. Throughout the 1950s and ‘60s, the Rastafari shifted their priorities to articulating their African identity and organizing for repatriation. Prior to his death in 1940, Marcus Garvey had sworn off Emperor Selassie, along with his fellow Jamaicans who worshiped him as Jah Rastafari; however, many Rastafarians held on to the notion that Garvey was a prophet who, like John the Baptist had done prior to Jesus’ ministry in Judea, acted as the forerunner to the messiah. Rastafari communities continued to find themselves in conflict with the colonial authorities, and their support for Selassie during Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia prior to World War II further polarized the movement from European Christianity, especially as the Pope of Rome expressed his support for Mussolini. While much of the Christian hymnody of Rastafari’s early years was retained, some Rastas made a serious effort to develop an African style of worship music, influenced primarily by the Buru drummers with whom they had frequent contact. 10 This musical innovation came to be known as Nyahbinghi drumming and chanting, and its “heartbeat” rhythm eventually found its way into the rhythms of Jamaica’s popular reggae music. Count 9 Barry Chevannes, Rastafari: Roots and Ideology (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1994), 153. 10 Verena Reckord, “From Burru Drums to Reggae Ridims: The Evolution of Rasta Music,” in Murrell, Spencer, and McFarlane, Chanting, 238. 7 Ossie, who took the lead in developing the Nyahbinghi sound, taught his style of drumming to students at the scattered Rasta communities around Kingston, and it was with this music that the Rastafarians greeted Selassie upon his visit in 1966. The arrival of the emperor was a pivotal moment for his Jamaican admirers, vindicating their claims to an African identity, and motivating many Rastafarians to organize and centralize in their efforts to repatriate. The last stage of the Rastafari movement that Chevannes outlines is characterized by a trend that continues among many Rasta communities around the world. In the early 1970s, the message of Rastafari began to spread throughout the Caribbean and into the United States and Europe, due in part to immigration from the West Indies into cities like New York and London. Perhaps the most influential factor in the spread of Rastafari was the adoption of its teachings into the lyrics of reggae musicians such as Bob Marley, Jimmy Cliff, and Lee “Scratch” Perry. Reggae fans around the world were attracted to Rastafari by its messages of peace, African and international unity, love for all, a connection with nature, and the use of ganja for meditation. Back in Jamaica, however, the several Rastafari mansions (sects)11 continued to evolve in different directions. While some groups remained relatively isolated from Jamaican society, the Twelve Tribes of Israel emerged as a branch of the movement that accepted middle class Jamaicans into its fold, allowing them to retain some of their Christian expressions of faith, practice a less strict lifestyle, and associate with non-Rastafarians in everyday life. For Twelve Tribes and unaffiliated Rastas around the world, the faith is more flexible than it is for other mansions, allowing more personal interpretation of the Bible and the events surrounding the rise of Haile Selassie and the reports of his death in 1974. One of the most critical tenets of faith that This term is explained by Rastas as a realization of Jesus’ saying in the Bible, “In my Father’s house are many mansions.” Despite the differences between Rastafari’s mansions being, in some cases, sources of division, there remains a sense that all are connected by their commitment to Haile Selassie and African unity. 11 8 varies in interpretation is the obligation to repatriate. While, for many Rastas, a literal return to Africa is the primary goal of the movement, others conceive of repatriation in spiritual terms, reasoning that a follower of Selassie can arrive at a spiritual state of Zion or Africa through the purification of his or her heart. Regardless of the weight given to any particular rule or commitment to a traditional motivation, Rastafarians universally embrace Africa as a symbol of hope, pride, and collective identity. Beardsmen, Combsomes, and Natty Dreadlocks By the 1930s, some adult males in the Rastafari movement had begun growing their beards, some of them connecting the significance of facial hair with passages in the Bible,12 along with the fact that Haile Selassie wore a beard. According to Chevannes, some of the first Rastafarians taught that only those with beards would be repatriated in August of 1934,13 and despite the clean-shaven norm in Jamaica, members of this new religious sect wore their beards with pride, distinguishing themselves from a British-dominated society that they saw as oppressive and evil. Another emblem of beauty in European society was straight hair, and the first Rastas were among the many Africans in diaspora who recognized the hegemonic influences dictating how “good hair” was supposed to be maintained. Having already found a religious motivation for the wearing of beards, Rastafarian communities further embraced the Nazirite vow, shunning the razor and letting their hair grow long. It is not clear which Rasta community or leader was directly responsible for the decision to abandon the common practices of trimming and straightening hair, but an untrimmed face and head were rather typical of 12 Num. 6:5, NKJV. This chapter of one of the books of Moses describes the Nazirite vow, which many Rastafarians attempt to follow very closely: no trimming of the hair, no alcohol, and no contact with dead bodies. 13 Chevannes, Rastafari, 155-158. 9 Rastafari by the end of the 1940s, earning them the disdain of those in Jamaica who thought these members of a strange new cult to be dirty or unkempt. The introduction of dreadlocks within the movement is also a mysterious moment in history, albeit a logical development in the gradual rejection by Rastafarians of social norms in Babylon (a term used early on in the movement to refer to colonial oppression, now used more broadly to refer to injustice and mental slavery). While this vague hypothesis seems to be the most reliable explanation for the emergence of Rastafari’s signature hairstyle,14 other stories that have been passed down through oral tradition are equally important in understanding the significance of dreadlocks. One such legend is that the guards at Leonard Howell’s commune wanted to acquire a more intimidating appearance in order to ward off the authorities, so they modeled their hairstyle after the fierce look of the Mau Mau warriors who fought against British authorities in Kenya. Another tradition, one that Chevannes dismisses for lack of evidence,15 is that the first Rastas who wore dreadlocks were inspired by the Hindu sadhus who grew and matted their long hair as part of their extremely ascetic lifestyle. Incidentally, these same holy men of India are those whose sacramental use of marijuana is said to have influenced Howell’s Rastafari community to adopt ganja for their own eucharistic purposes. Another possibility that may be inferred from the ethnographic research of Jake Homiak is that the dreadlocks trend began – or at least became popular among the Rastafari – when an especially ascetic group called Higes Knots emerged around 1950. These bredren16 went around “barefoot, with matted hair, 14 Chevannes, Rastafari, x. Ibid. 16 The Jamaican pronunciation of the term “brethren,” which is preferred by Rastas over the word “men.” 15 10 cloaked in crocus bags, and armed with large rods,”17 and they had a profound influence on the development of I-tal livity, being as much admired by the Rastafari as they were disdained by the colonial society. Regardless of any factual explanation for the emergence of dreadlocks, which by now is highly unlikely to be discovered, the stories that have been recorded since the 1970s reveal memories and perspectives about the social contexts, ideals, and eschatological hopes of the earliest Rastafarians. Resistance against colonial white notions of beauty, connection with African cultural expressions, an ascetic reverence for nature, and a need to inspire dread in the hearts of their Babylonian enemies – whether these be motivations for the first dreadlocks or afterthoughts that took hold in oral tradition, these various meanings ascribed to Rastafari’s most long-standing cultural symbol reflect some of the values universally accepted by the movement. However, it has been said that dreadlocks were a point of contention between mansions for several years. Members of the Youth Black Faith, among whom it is thought that the dreadlocks style first emerged, eventually made a distinction between their “Combsome” bredren – those who may have grown their hair but prevented it from becoming matted – and the Dreadlocks Rastas. Within some communities, dreadlocks eventually became a compulsory expression of commitment to Rastafari; Chevannes recounts a lecture by an elder about the necessity (but not sufficiency) of dreadlocks for personal salvation.18 This has certainly changed since the international spread of Rasta culture and the more flexible varieties of the faith found in the Twelve Tribes and more recently established communities. Even as the internal differences over dreadlocks highlight some of the issues about the sustainability of symbolic meaning, which I John P. Homiak, “Dub History: Soundings on Rastafari Livity and Language,” in Rastafari & Other African-Caribbean Worldviews, ed. Barry Chevannes (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1998), 151. 18 Chevannes, Rastafari, 248-49. 17 11 will address below, the universal recognition of this hairstyle as an expression of Rastafarian ideology indicates its value as a window into the cultural mind of the movement. Persecution of the Dreadlocks If every man was equal, you see There would be none of this poverty And they could not trim the dreadlocks in prison Victimization would have to stop They could not trim the dreadlocks in prison Liars and thieves would not be cops (Max Romeo, “Revelation Time”)19 In the late 1950s and early 1960s, conflict between the Dreadlocks and Jamaican authorities escalated, occasionally leading to the brutal treatment and killing of Rastafarians. Police raids included the breaking of the Rastas’ sacred drums and chalices (water pipes), beating of men and women, and trimming or ripping out of the dreadlocks, sometimes tearing out flesh with the hair.20 Widely considered among Rastas as the climax of oppression against Rastafari, the Coral Gardens Incident in April of 1963 was also a turning point in the relationship between the movement and mainstream Jamaican society. Independence from Great Britain had been achieved only a year before, and although the University of the West Indies had published a report in 1960 dispelling many of the misconceptions about Rastafari, the new nation was still dominated by European notions of civilization, to which the untrimmed, ganja-smoking, drumpounding, strangely speaking Rastafarians did not measure up. The “Bad Friday” incident, so called because the violence erupted in Coral Gardens on Holy Thursday and lasted throughout Easter weekend, as the police and military raided camps throughout the western side of the island. Following this mass persecution, many Jamaicans began to sympathize with the Rastafari 19 20 Max Romeo, “Revelation Time.” Revelation Time. LP. Tropical Sound Tracs, 1975. Yasus Afari, Overstanding Rastafari (Jamaica: Senya-Cum, 2007), 56. 12 movement,21 and tolerance for their lifestyle has gradually improved ever since. The acceptance of Rastafari as culture bearers in Jamaica did not occur overnight, however; Max Romeo’s refrain in “Revelation Time” suggests that the trimming of prisoners’ dreadlocks may have still been in practice during the early 1970s, and the prohibition of sacramental ganja use continues to this day (although it seems to be rarely enforced in Jamaica). Bob Marley’s international renown spread awareness of Rastafari culture around the world through the 1970s, and the movement’s message of “peace and love” was welcomed among the American and European music scenes, where long hair and marijuana were also indicative of group identity. Like the stigma assigned to hippies all over the US, the arrival of dreadlocked Rastafarians in American cities was greeted with fear and suspicion. Drug use and trafficking were naturally among the accusations directed toward Rastas, who have never attempted to hide their veneration for the “holy herb;” however, the fear of this revolutionary movement went much further. The media labeled Rastafarians as Marxists, sympathizers of Fidel Castro, terrorists, organized criminals, and cult members.22 It certainly did not help that MOVE, a radical group founded in West Philadelphia during the 1970s, were primarily AfricanAmericans with dreadlocks. Even comedian Eddie Murphy helped to reinforce these misconceptions when he appeared as his popular Saturday Night Live character, Tyrone Green, singing, “Kill the White People,” portraying Rastafarian reggae musicians as violent black supremacists and hypocrites who perform their music for financial gain, rather than for the sake of the art and its message.23 Horace Campbell, “Coral Gardens 1963: The Rastafari and Jamaican Independence,” Horace Campbell (blog), April 17, 2013 (11:34 a.m.), http://www.horacecampbell.net/2013/04/coralgardens-1963-rastafari-and.html. 22 Chevannes, Rastafari, 264-68. 23 From Saturday Night Live, Season 8, Episode 6. 21 13 Although the dreadlocks hairstyle has become much more common, and the Rastafari movement is no longer subjected to the same degree of profiling by law enforcement, there is still a sense that the appearance of locks is unprofessional or undesirable in certain communities. The business school at Hampton University, for example, banned its students from wearing dreadlocks or cornrows in 2001, and the administration continues to defend its ban, despite objections from students who argue that these hairstyles are expressions of their black identities.24 On the other hand, some wearers of dreadlocks maintain thinner, more even locks, a more acceptable look compared to the thicker, more uneven, traditional locks of Rastafarians. Athletes, musicians, and other celebrities wear this style, receiving little or no criticism for their appearance. In many professions and communities, however, dreadlocks are still considered unclean, unprofessional, and suggestive of a subversive or criminal tendency.25 Meaning and Function Yasus Afari, a Jamaican dub poet and Rastafarian scholar, describes the dreadlocks as a means of commitment to God as well as a connection to the natural world. They are the Roots that anchor us in the Cosmic Mind, Intelligence and Consciousness of the Most High, as well as the Antennae that [connect] us to the spiritual existence. In essence, the “dread locks” is the tangible testimony, extension, identity and manifestation of the Faith and Covenant between The RASTAFARIANS, and The Most High, JAH RASTAFARI.26 More than merely an example of ascribing new meaning to an existing symbol, this explanation of the role that dreadlocks play in the spiritual lives of Rastafarians reveals two important themes David Ham, “HU Business School Dean Stands by Dreadlocks, Cornrows Ban,” ABC 13 News (Hampton, Virginia), August 20, 2012, http://www.wvec.com/my-city/hampton/Businessschool-dean-stands-by-ban-on-dreadlocks-and-cornrows-166809246.html. 25 Dawn Turner Trice, “Have Dreadlocks Outgrown Their Old Meaning?” Chicago Tribute (online version), March 25, 2013, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2013-03-25/news/ct-mettrice-dreadlocks-0325-20130325_1_dreadlocks-north-austin-neighborhood-black-hairstyles 26 Afari, 103, emphasis in original. 24 14 in the movement’s cosmology: the idea that spiritual or cosmic energy may be accessed through bodily expression (this has been more thoroughly explored in Rastas’ ideas about music and word-sound power, or creative use of language); and the experience of faith as a “tangible” reality, rather than a “pie in the sky” belief system. As with their chanting and drumming, which are intended to send energy into the environment in order to affect positive change, the shaking of dreadlocks is also a means of releasing a spiritual force that works to destroy the Babylon system.27 If the growing of dreadlocks was a natural evolution of resistance against European norms of beauty, it may be argued that this notion of sacred energy in Rastas’ locks is a further development of the movement’s effort to redefine African phenotypes as beautiful and powerful. Regardless of whether the dreadlocks’ energy is material or social in nature, the wearing, shaking, and wrapping of the matted locks of hair certainly appear to evoke emotional and meaningful responses. Rastafarians have a variety of ways of wearing and covering their dreadlocks. The Boboshanti mansion, also known as the Ethiopia Africa Black International Congress (EABIC), practices a strict livity modeled after some of the laws in the biblical book of Leviticus, as well as the practices of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Although they may not be the only Rastafarians who wear turbans (see Figure 1), this method of wrapping the locks is a requirement for Bobo males; the empresses (females) also wear head coverings and follow strict regulations regarding modesty in dress and cleansing during menstruation. One Boboshanti priest explained the wearing of the turban as a “form of vow” that demonstrates respect for one’s divinity,28 but I have not heard any thoughts on why the turban is more appropriate than other hair coverings. Ennis B. Edmonds, “Dread ‘I’ In-a-Babylon: Ideological Resistance and Cultural Revitalization,” in Murrell, Spencer, and McFarlane, Chanting, 32. 28 Personal communication with anonymous Boboshanti priest in Philadelphia, May 2014. 27 15 When I visited the Bobo camp in Bull Bay, Jamaica, my guide (a Nyahbinghi elder) and I were asked to remove our tams (see Figure 2) upon entering the gates, which seems to indicate that there is a preference for hair being exposed rather than wrapped in something other than a turban. For the Nyahbinghi Rastas, by contrast, there seems to be no strict or universal rules regarding how locks are worn, other than the mandatory removal of head coverings (for males) inside of the tabernacle. Some wear various styles of caps known as tams and crowns, which contain some or all of their locks, and those whose locks are long enough often fix them on top of their heads in a style also known as a “crown” (see Figure 3). This term calls to mind the Rastafarian resistance against hierarchy, the notion that all individuals are royalty, which is why they commonly address each other as king, queen, Ras, or empress. Figure 1: Priest Oucal of the EABIC (right) at the Bobo Hill camp, Bull Bay, Jamaica, making the sign of the trinity with the author. In addition to his turban and white Sabbath robe, he is wearing his beard locks in a style known as a “precept,” a term that indicates the significance of locking as a moral covenant. Photo by Christopher Cooper. 16 Figure 2: Bongo Shephan, an elder in the Nyahbinghi Order, often wears his dreadlocks in a tam. Hand-woven in many different styles, tams are media in which Rastas can display symbols of the faith – in this case, the red, gold, and green of the Ethiopian flag. Photo by author. 17 Figure 3: Ras Ayenton wearing his dreadlocks in a “crown” style. When he unwraps them, they are long enough to reach the ground. Displaying the length of one’s locks is a way of showing how long one has been “on the trod,” that is, following the Rastafari livity. Photo by author. In their discussion of Rastafari in the context of social movement psychology, Kebede et al outline two major functions of the dreadlocks: (1) a means of delineating group boundaries and (2) a resistance against the dominant social norms, which entails an effort to connect with nature in ways that the Babylon system has suppressed through technology and chemical grooming products.29 Having already explored the latter function through an historical lens, I now return to a consideration of the former, the role of dreadlocks in expressing and negotiating AlemSeghed Kebede, Thomas E. Shriver, and J. David Knotterus, “Social Movement Endurance: Collective Identity and the Rastafari,” Sociological Inquiry 7, no. 3 (2000): 323. 29 18 Rastafarian identity. While this function has been clearly established in previous historical and ethnographic literature, I offer my more recent findings as examples of how the dreadlocks phenomenon has evolved within the movement. Much of the symbolism remains unchanged; however, the attitudes of my interlocutors regarding the relevance or necessity of dreadlocks raise questions about the longevity of cultural symbols as tools for empowering a sense of collective identity. Appropriation and Authenticity During my visit to the Nyahbinghi Tabernacle in Scott’s Pass, Jamaica, in 2010, one of the priests addressed my questions about authenticity and music by making an analogy to the dreadlocks: “You know how much years it takes [to] put locks on, and right now you can go into the barbershop, and within minutes you come out with locks.” Another Rastaman replied, “You can get it to buy. Commercial.” My guide, Bongo Shephan, referred to this phenomenon as “Rentalocks,” and I have heard others call them “fashion dreads” and refer to non-Rastas with dreadlocks as “wolves” – that is, these wolves in sheep’s clothing may be infiltrating the movement with the right appearance but the wrong intentions. As the hairstyle continues to be commodified in many parts of the world, the appropriation of dreadlocks by non-Rastas, especially those who express no interest in Rastafari faith or culture, is considered disrespectful by many Rastas, especially those who lived through the persecution of Dreadlocks Rastas in the mid-20th century. Rather than publicly condemn this practice, however, Rastafarians seem to adhere to their “judge not” mantra; while I have not discussed dreadlocks at length with any Rasta community, the general attitude toward appropriation of reggae music was that people are free to do as they choose, and the Rastafari movement is in no position to prevent others from expressing themselves in this manner, even if it is less authentic or disingenuous. As many 19 celebrities and non-Rastas have taken on a more manufactured version of dreadlocks, Rastafarians have been challenged to reconsider the role of hair as a cultural boundary. B. Davis is a reggae singer from Trenton, New Jersey, who has been involved in the Rasta and reggae communities for nearly two decades. Noticing that his hair was growing longer again, several years after he trimmed his own dreadlocks for reasons he has not discussed with me, I asked him if he planned on locking up again. In very few words, he explained that, while he had a couple of locks naturally forming already, he was not sure if he would continue growing them, as there are many complicated issues regarding dreadlocks. He did not cite his racial identity, but I imagine that his categorization (not necessarily identification) as a white man may influence his experiences as a dreadlocks-wearing, Twelve Tribes Rastaman. Davis later mentioned that one of the gangs in Trenton recently started wearing dreadlocks as part of their gang identity markers. In all of my conversations with him over the last few years, I have never heard him take offense to anything; but when he described this dreadlocked group of violent criminals, his tone became one of righteous anger as he expressed his wish for this group to cut off their locks. That he would have this attitude toward gang members, but not to hippies or other “wolves,” reflects the priorities of many Rastafarians: delineating group differences is far less important than condemning violence. When I asked Jah1, another reggae singer in the Philadelphia scene, what his dreadlocks mean to him, his initial response was, “To me, it’s just hair.” Convinced that there must be more significance behind his long locks, I prodded for several minutes, referring to Coral Gardens and the legacy of dreadlocks in Jamaica, where Jah1 was born and raised. He acknowledged that the hairstyle had been very important in the past, but now that it is virtually useless in distinguishing Rastafarians from non-Rastas, it was nothing more than a hairstyle, in his opinion. He did recall, 20 however, that the majority of people in his childhood community regarded the appearance of Rastafari as dirty and unattractive – “the kind of people you don’t want to be around.” With a Christian mother who would not allow him to grow dreadlocks while he lived in her house, he looked forward to the day when he could move out and grow locks like his Rastafarian father. He explained nothing of the religious significance, and perhaps his affiliation with the Twelve Tribes mansion has provided him with few reasons to perceive dreadlocks in this way; however, he did make a connection between the simplicity and frugality of his lifestyle and his decision to regrow his locks after cutting them several years ago. “The barber doesn’t like us much,” he said to me, in reference to my admission that I cut my own hair with electric trimmers. “We don’t give no money to the barber.” Although we have very little in common with regard to our hair, he established a “we” according to our shared value of simplicity over vanity. Conclusion: Sustaining and Stretching the Symbol While I do not mean to suggest that the appropriation of dreadlocks poses a real threat to the endurance of the Rastafari movement, it is crucial for Rastafarians to consider the current evolution of cultural symbols and practices in order to evaluate their relationship to Babylon, as well as internal relations. The emerging field of cultural sustainability engages such discourses in ways that go beyond notions of preservation, intangible heritage, and cultural rights. By invoking an ecological model, the concept of “sustainability” may inform a deeper consideration of the diverse factors that inform collective identity, allowing room for Rastafarians to create new meanings out of traditional interpretations of their own cultural phenomena. In the case of the dreadlocks, it is quite possible that the “don’t haffi dread” philosophy will continue to coexist with the disciplines that mandate locks and turbans, as advocates of each persuasion challenge and reinforce a variety of convictions through dialogue. In a sense, Rastafari already has a 21 mechanism in place that facilitates the “flexification”30 of cultural meaning: reasoning, group participation in sacred, loosely structured conversations, is an activity that allows every Rasta to express his or her voice on important issues, with equal consideration for all participants, regardless of age or social status. I believe that it is within the continued practice of reasoning that the Rastafari movement will rediscover, revitalize, redefine, and perpetually challenge traditional notions of significance and identity. Whether dreadlocks become more or less common among Rastafarians, the meaning will not be lost; to the contrary, it will be found and flexed in as many new ways as there are Rastas who have the opportunity to reason with their bredren and sistren in the sustaining process of cultural invention. 30 Jake Homiak offered this word to me at my undergraduate thesis defense as a characterization of Rastafarians’ ability to adapt and create meaning when faced with contradictions and challenges to their livity. 22 Bibliography Afari, Yasus. Overstanding Rastafari. Jamaica: Senya-Cum, 2007. Bob Marley and the Wailers. “Rastaman Live Up.” Confrontation. LP. Tuff Gong Records, 1983. Campbell, Horace. Rasta and Resistance. Trenton: Africa World Press, 1987. Chevannes, Barry. “Rastafari and the Exorcism of the Ideology of Racism and Classism in Jamaica.” In Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader, edited by Nathanial Samuel Murrell, William David Spencer, and Adrian Anthony McFarlane, 55-71. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998. Edmonds, Ennis B. “Dread ‘I’ In-a-Babylon: Ideological Resistance and Cultural Revitalization.” In Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader, edited by Nathanial Samuel Murrell, William David Spencer, and Adrian Anthony McFarlane, 23-35. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998. Garvey, Marcus. The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, edited by Amy JacquesGarvey. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1925. Ham, David. “HU Business School Dean Stands by Dreadlocks, Cornrows Ban.” ABC 13 News (Hampton, Virginia), August 20, 2012, http://www.wvec.com/mycity/hampton/Business-school-dean-stands-by-ban-on-dreadlocks-and-cornrows166809246.html. Homiak, John P. “Dub History: Soundings on Rastafari Livity and Language.” In Rastafari & Other African-Caribbean Worldviews, edited by Barry Chevannes, 127-81. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1997. Kebede, AlemSeghed, Thomas E. Shriver, and J. David Knotterus. “Social Movement Endurance: Collective Identity and the Rastafari.” Sociological Inquiry 7, no. 3 (2000): 323 Lewis, Rupert. “Marcus Garvey and the Early Rastafarians: Continuity and Discontinuity.” In Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader, edited by Nathanial Samuel Murrell, William David Spencer, and Adrian Anthony McFarlane, 145-58. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998. Reckord, Verena. “From Burru Drums to Reggae Ridims: The Evolution of Rasta Music.” In Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader, edited by Nathaniel Samuel Murrell, William David Spencer, and Adrian Anthony McFarlane, 231-52. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998 Romeo, Max. “Revelation Time.” Revelation Time. LP. Tropical Sound Tracs, 1975. 23 Spencer, William David. “The First Chant: Leonard Howell’s ‘The Promised Key.’” In Chanting Down Babylon: The Rastafari Reader, edited by Nathanial Samuel Murrell, William David Spencer, and Adrian Anthony McFarlane, 361-89. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998. Trice, Dawn Turner. “Have Dreadlocks Outgrown Their Old Meaning?” Chicago Tribune (online version), March 25, 2013, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2013-03-25/news/ctmet-trice-dreadlocks-0325-20130325_1_dreadlocks-north-austin-neighborhood-blackhairstyles 24