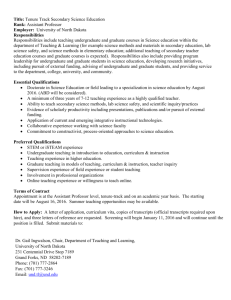

Teaching Philosophy - The Center for Teaching and Learning

advertisement

Introduction: In July 1976, I was fortunate to join the faculty of UNC-Charlotte. I was fresh out of the University of Florida’s PhD Program, and I had come to the United States only nine years earlier as a political refugee from Uganda. I dreamed of being an aeronautical/ space engineer and thought university teaching would be something beyond my wildest dreams. As a thirty two year old, I had many hopes, fears, and expectations going into this first job, about everything from my students, to my colleagues, to my own career path. But I never would have guessed that I would spend more than thirty four fulfilling years – my entire career – at this incredible university, watching and contributing to the growth and successes of both the undergraduate and graduate engineering programs, as well as UNC-Charlotte as an institution. When I began teaching in 1976, I was offered the opportunity to start planning UNC-Charlotte’s graduate electrical engineering program. At that time, UNC-Charlotte had only undergraduate engineering programs, but that too, were new; there were five faculty members in the department and we only offered limited courses. Developing an engineering graduate program would be a challenge, but it was a challenge that I felt was worth devoting my career to fulfilling. During the early part of my career, I focused on developing our undergraduate electrical engineering program. I wanted to understand and truly appreciate undergraduate teaching before delving into the challenges of developing a graduate program. Most importantly, I wanted to become a good teacher. I taught four different undergraduate courses per semester, and focused my time on teaching undergraduate students basic engineering concepts which would lay the foundation for further graduate studies. I spent hours and hours each week preparing for my classes—figuring out the best ways to take complicated and abstract concepts and distilling them into simple, easy-to-understand explanations that my students would grasp. Four years later, I began focusing my efforts on developing the graduate electrical engineering program. Collaborating with the original, founding members of the departmental faculty, I had the privilege of initiating and teaching the very first graduate engineering course at UNC-Charlotte. I also directed the first Master’s thesis in the engineering college. And I was a member of all three committees that developed proposals for the first three doctoral programs at UNC-Charlotte Once the graduate programs in the college began developing, I served as the first graduate coordinator of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, and the first chair of the College Graduate Committee, as well as the Engineering College Representative in the newly formed University Graduate Council. Throughout the years, I have strived to incorporate my individual aerospace engineering research into the classroom by doing aerospace research in collaboration with NASA Langley Research Center either during summer months or during the academic year at UNC Charlotte through research grants. Over thirty four years that I have been teaching at UNC-Charlotte, the undergraduate and graduate engineering programs have exploded in size, quality, and caliber. Although my work at UNC-Charlotte has largely focused on developing and running the graduate electrical engineering program, and furthering my aerospace engineering research, I consider myself a teacher first. I am incredibly thankful to have worked with my talented and committed colleagues. And most importantly, I am thankful to have had had the privilege of teaching thousands of engineering students, and supervising and mentoring hundreds of graduate and undergraduate students. Looking back, I still cherish these early years of teaching undergraduates. And as a result, I always teach at least one undergraduate course per semester and direct at least one undergraduate senior design project per year. My Basic Teaching Philosophy: My teaching philosophy originates from my childhood education in Uganda, which was based on the traditional British system. Particularly for the sciences, teachers took responsibility for teaching students fundamental concepts in chemistry, physics, biology, and math in a comprehendible and comprehensive manner. And then the students took responsibility for applying those concepts and ultimately, solving complex problems using their knowledge of basic concepts. I never relied on formulas or even textbooks. Thanks to my teachers, my knowledge of the sciences, even today, relies heavily on my deep understanding of those same basic concepts I learned in the 50s and 60s. I have spent my career attempting to implement and refine that teaching methodology that I fondly grew up with. As a professor at UNC-Charlotte, I learned quickly that teaching is not merely lecturing to students. Rather, it is presenting material in a logical, precise, and clear manner that enables students to use their critical thinking abilities to integrate information into their knowledge base in a meaningful way. Teaching is also creating a dialogue in the classroom—facilitating and encouraging open discussions between the teacher and students, as well as amongst the students themselves. Such an active learning environment not only inspires students to learn, but also empowers them to take responsibility for their learning. I also believe that teachers also have an obligation to create an atmosphere that is conducive to learning. Teachers should bring excitement to the classroom and use creative ways to make students recognize the practical application of their education. For example, I always try and integrate recent developments in the engineering field into the classroom. One of the important lessons I have learned over the years, and one that I think about every single time that I stand in front of a classroom full of students, is that learning is a complex, individual process, and that good teachers must adapt to the needs of the students and the subject matter—forming a learning partnership. Consequently, I implement a broad range of teaching methods both in and out of the classroom to cater to individual students’ needs and goals. For example, I exercise special care in my class lectures to explain new engineering concepts clearly, precisely, and in multiple ways. I try and keep the class moving at a good pace, while incorporating interesting, real life examples for the interested students who learn quickly. At the same time, I try and keep my examples straightforward and logical, and occasionally throw in a few jokes, to keep the interest of students who may have academic background deficiencies or who simply are not interested in circuits. Recognizing that all students learn new concepts in different ways and at different rates, I constantly encourage students to meet with me outside of class. I always make it clear that my formal office hours are simply set times when I am guaranteed to be in my office, but that I am always available to meet with anybody whenever my door is open—which is always. I do not consider any question to be silly or basic and I do not mind reviewing any class material or helping students with professional goals. I have found that my time spent with students outside of the classroom has been incredibly rewarding. For students who struggle to keep up with the challenging curriculum, this is when I can give them the one-on-one attention. Additionally, every semester I schedule extra group help sessions. And for students who like the subject matter and want to be challenged further, this is when I can encourage them to assist me with my research or apply for related research jobs and internships. I strive to teach each of my students that engineering is so much more than electrical systems, computers, and networks.]. While an engineer in training must learn certain facts and concepts, the practice of engineering is actually using that knowledge in a creative and socially responsible manner. Hence, while teaching a course, apart from regular exams and assignments, I usually assign several design projects during the semester, in which students have to not only incorporate new ideas and concepts that they learn in class, but address global and societal issues, like the environment, economics, ethics, and safety. I do not see a rigid line separating research and teaching. Teachers should be involved with research so that they can help students understand how what they are learning in the classroom applies to real life. And students should be involved with research to help prepare them for their professional careers, whether they are practicing engineers or are pursuing further graduate studies. Interestingly, it has been my experience with undergraduate students, that there is a tremendous amount of “mysticism” associated with research. During my tenure at UNC-Charlotte, I have tried to address this issue by encouraging undergraduate students to participate in my own research projects, and I pair them up with my graduate students. I believe that qualified, undergraduate students at UNC-Charlotte should be encouraged to pursue their graduate education at UNC-Charlotte, and I have worked hard to supervise and retain many of them. Of the six doctoral students I have graduated so far, two of these students received their undergraduate degrees at UNC-Charlotte. Over the years, I have also been successful in directing over forty Master’s students; of this group, about 40% of them received their undergraduate degrees at UNC-Charlotte. I recently supervised two Master’s degree students who had completed their undergraduate degrees in our department, and they went on to complete their Ph.D. degrees—one at MIT and the other at Stanford University. My graduate courses are highly interdisciplinary and provide students with a foundation for conducting research in numerous areas of engineering. During the past six years I have graduated six Ph.D. students, which is one of the highest in the college, if not the highest. I have also directed four Master’s students with the thesis option during this period. Currently, I am directing three doctoral dissertations—all of which are close to their graduation. In my opinion, motivating graduate students to pursue excellence in research and scholarship is the most important aspect of a strong graduate program. I believe in developing a strong bond with my graduate students because they need constant intellectual stimulus as well as an atmosphere to realize their full potential. This requires me to remain current in my own research, so that I can provide them with exciting and state-of-the-art research ideas. Additionally, I have to provide them the necessary academic background so that they can consult the latest relevant research. I hold frequent meetings with my graduate students where they discuss their research, and I discuss my own, with the hopes of creating a research culture of constant exchange among peers. I have students that are working on exciting projects, such as designing future spacecrafts and space robotics, and a shape memory alloy-based robotic hand that can perform surgery from a remote location. I consider teaching a tremendous opportunity to inspire and empower students with knowledge that will literally change the world Accomplishments In 1984, I was the first faculty member at UNC-Charlotte to be awarded a federal research grant from the NASA Langley Research Center. I have also received external grants every year since and have been a CO-PI on other grants. Such funding has allowed me to expose current research areas to graduate students, and to help provide them with financial assistance over the years. Additionally, grant funding gives my students the opportunity to accompany me to research laboratories and conferences, where they interact with national and international research scholars from around the world. Additionally, I have coauthored a number of papers in national and international conferences as well as technical journals with my graduate students based on their research work. I always encourage my students to present their research at these conferences because it provides them with an invaluable opportunity to develop a sense of belonging amongst other research scholars. For example, during the initial stage of my research funded from NASA Langley Research Center, a lot of my research work involved experimental work, where I spent a great deal of time with my graduate students at the actual NASA laboratories. These graduate students loved working side-by-side with NASA scientists and technicians, and most of those students have earned graduate degrees and pursued careers in aerospace engineering. While I conducted my NASA research project, I teamed up with aerospace researchers at other North Carolina Universities to form the NASA-sponsored N.C. Space Grant Consortium. We secured an annual block grant for the member universities primarily for undergraduate scholarships and graduate fellowships. The consortium also provided financial and academic support for summer internships at various NASA centers. Consequently, I have been able to send one graduate intern per year to either NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston or NASA’s Goddard Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. These unique opportunities have helped me to recruit bright undergraduate and graduate students to become involved in aerospace-related research. Also, I was the UNC-Charlotte Campus Director of the N.C. Space Grant Consortium from 1993 to 2008. This position provided me with a tremendous opportunity to work with highly-qualified students pursuing careers in aerospace science and engineering, which is an area with a declining number of scholars due to retirements. I am proud that most of the graduates I have supported during my career have completed their education at the Master’s level and have found challenging careers in the aerospace industries. I am currently directing three doctoral dissertations and one Master’s thesis, and am serving on twelve other doctoral committees. I strive to help all of these students maximize their time at UNC-Charlotte in various ways including seeking financial support for them from my research grants, industrial sponsorships through extended internships, or departmental assistance. I work very hard for them to be successful not only during their academic studies at UNC-Charlotte, but I routinely help them identify their career goals and provide them with the necessary contacts for job opportunities. The following are the names and dates of graduation of these doctoral students: Surya Kumar Ashok Kumar: May 2005 (Supported by Intel Corporation) Hazem B. Alassaly :December 2005 (Supported by the department and research grants) Ronald Steven Black: December 2007 (Supported by AREVA Corp.) Vikram Karwal: August 2009 (Supported by the department and research grants) Douglas Isenberg: December 2009 (Supported by research grants) Kamal Sundersan: May 2010 (Supported by Texas Instruments) In addition to working and mentoring my own doctoral students in the past six years, I have served on nine other doctoral committees at UNC-Charlotte and one doctoral committee at the University of the West Indies, Trinidad. I have also served on over twenty other Master’s committees in various departments during the last six years.