The Cuban Missile Crisis was, in essence, one

advertisement

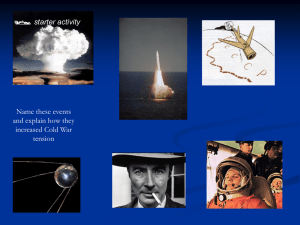

Crisis Management and Decision Making of the Cuban Missile Crisis Michael Ginsburg Southern Utah University The Cuban Missile Crisis was, in essence, one of the most dangerous moments in the history of the United States. Those two weeks in October were some of the scariest moments for American citizens, with what seemed like the inevitability of a nuclear war knocking on the door of the U.S. The country survived, though, through the leadership and crisis management skills of President John F. Kennedy. To see how this leadership was carried out, though, is remarkable. Graham Allison applied his three models of decision making to the Cuban Missile Crisis in his book, Essence of Decision. Each model, as he explains throughout his book, is responsible for helping form some part of the United States’ foreign policy during this crisis, and how the leaders of the country helped save it from destruction. Graham Allison, in his book, introduces three different models of decision making that he believes helps explain the decisions made during the crisis. His models are: The Rational Actor Model, the Organizational Behavior Model, and the Governmental Politics Model. While each model explains a different way that a policy is decided, they each contribute some sort of valuable viewpoints on different decisions made during the Cuban Missile Crisis. By analyzing different events of the crisis and asking certain questions, Allison applies the models’ to the Cuban Missile Crisis, and helps explain some of the events that occurred during the crisis. The overall consensus on foreign policy, though, is that some one person or group (the federal government) should handle the foreign policy of our country. According to Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. “…confronted by presidential initiatives abroad, Congress and the courts, along with the press and citizenry too, generally lack confidence in their own information and judgment. In foreign policy the inclination is to let the Presidency have the responsibility-and the power.” (Arthur M. Schlesinger, 1986) The Rational Actor Model assumes that the leader, or in this case the government of a country, is looking at all of the evidence objectively and makes the most logical decision. This is one of the more basic concepts of decision making. It assumes a rational person or group is interested in the information, is taking all possibilities into thought, and from all the information and all of the confusion, the actor makes the most rational, well thought out decision they can make. Allison notes in his book what some of the core concepts are for an action to be considered rational: Having goals and objectives, having alternatives, understanding the consequences, and making a choice based off of those. (Allison, 1999) By going through this process and understanding how one picks a rational decision, we can then better understand the thought process that might have occurred during the crisis. When applied to the Cuban Missile Crisis, one can give several examples of the Rational Actor Model in effect. It is easy to see that Kennedy, acting as the leader of the United States government, used reasoning and logic to make his final decisions on the foreign policy of the country during this stressful time. The best example of this would be Kennedy’s decision to “quarantine,” Cuba rather than attack, blockade, or commit any other acts of war. As Allison notes in Essence, Kennedy had at least six other alternatives, including military strikes against Cuba. “The United States had thought about logical Soviet countermoves, especially on Berlin. … President Kennedy overruled suggestions that the blockade should be extended to the necessities of life in Cuba, reasoning that therefore the Soviets might be less likely to reciprocate with an identical blockade of Berlin and the danger of an escalation to war would be reduced.” (Allison, 1999) While the final product of the United States foreign policy was decided and executed by a rational actor; that is just one of many decisions that were affected during the crisis. While Kennedy acted as the “rational actor,” he did not work alone in dealing with this crisis. There were different agencies and individuals in the government who helped Kennedy understand the situation and who made decisions that influenced the decisions made at the top of the chain of command. This is essentially what the Organizational Behavior Model tries to explain. In his lecture at Southern Utah University on the subject, Dr. Michael G. Stathis said that the Organizational Behavior Model was the, “idea that government runs as a functioning organization in a fast pace.” He also said that it can be described “government as machine.” (Stathis, 2014) When discussing the model in his book, Allison says, “In Model II (Organizational Behavior) explanations, the subjects are never named individuals or entire governments. Rather, the subjects in Model II explanations are organizations, and their behavior is explained in terms of organizational purposes and practices common to the members of the organization, not those peculiar to one or another individual.” (Allison, 1999) So, it is easy to apply this model to the Kennedy administration as well as the Soviet Union. A simple example of how this model could be applied to the Kennedy administration regarding the Cuban Missile Crisis is how the crisis even became known. The Air Force was running routine flying surveillance when a U-2 aircraft noticed the nuclear arsenal being built in Cuba. It took photos of the missiles, and as the chain of command of the Air Force requires, the information reached was passed along and was eventually given to the president. The organization that is the Air Force followed procedure and helped contribute to the helping the United States. A lesser known example of this model is the decision by the Soviet Union to actually arm Cuba. As Allison notes, “Though the U.S. did not know it, the Cuban requests for conventional weapons to aid their defense were approved by the governing Soviet Presidium in April 1962. In their path-breaking work, Alexander Fursenko and Timothy Naftali note that the Presidium chose to divert surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) already promised to Egypt to Cuba instead. They identify the separate decision-making process initiated by Krhushchev that six weeks later produced the Presidium’s decision to send nuclear missiles to Cuba.” (Allison, 1999) The government of the Soviet Union had different groups and agencies, and all of them contributed in some way to the crisis. This group had already decided that they should arm Cuba, and they continued on that path. A means to an end must go through different agencies and groups involved, and they all will have a say in the final decision. This is where Graham Allison’s Organization Behavior model and his last model, the Governmental Politics model, intertwine and become very similar. In the model of Governmental Politics, each agency makes some decisions, and they each have some say in the decisions made. Each decision is a compromise where each agency and group has a say and a vote. No one person or group controls the decision making process, but it is rather decided through compromise. This tends to lead to decisions that aren’t the best for the situation, but they are good decisions that everyone agrees with. Allison uses the final compromise as a good example of the Governmental Politics model in practice. The removal of the United States missiles in Turkey, which were meant to be dismantled for some time before the crisis, became a key term that everyone involved in the crisis agreed upon. The decision, like all the other decisions, had to be made, though, to act. The models of Graham Allison’s book Essence of Decision gives three models of understanding how decisions are made. He uses the Cuban Missile Crisis as a case study, and applies the models to the crisis. Whether one person, an agency, or a quorum make the decision, a decision and path of action are made that will be followed out. Each model, the Rational Actor, the Organizational Behavior, and the Governmental Politics, have valid points and uses in the way decisions are made. Each model was used sometime during the crisis, and they all are involved in any crisis. There is no best way to make a decision, as Allison points out and shows using the models. It is the maker of history that will decide how to interpret the decisions that were made by those in the past. References Allison, G. (1999). Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missle Crisis. Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers. Arthur M. Schlesinger, J. (1986). After the Imperial Presidency. In J. Arthur M. Schlesinger, The Cycles of American History (p. 277). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. Stathis, D. M. (2014, February 11). Cedar City, Utah.