What is a green lease? - Department of Industry, Innovation and

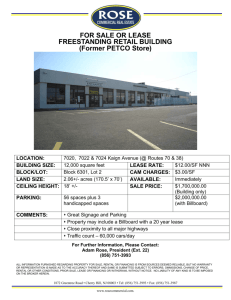

advertisement