HCAI - South East Public Health Observatory

advertisement

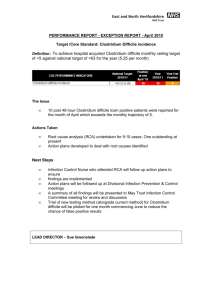

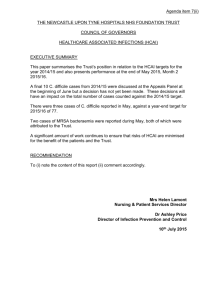

HCAI Risks, burden, process and control Elizabeth Haworth HPA SE January 2008 Background • • • • • • Policy Incidents High rates of infection Measurable infection rates Interpretable infection rates Evidence Definition Healthcare associated infections (HCAI) are infections that are acquired in hospitals or as a result of healthcare interventions. There are a number of factors that can increase the risk of acquiring an infection, but high standards of infection control practice minimise the risk of occurrence. Policy Documents 11 January 2008 Revised code of practice for the prevention and control of healthcare associated infections 9 January 2008 This document draws together recent initiatives to tackle healthcare associated infections and improve cleanliness and details new areas where the NHS should consider investing to ensure that patients receive clean and safe treatment whenever and wherever they are treated by the NHS Clean, safe care: reducing infections and saving lives 18 December 2007 This paper presents an analysis of the contribution of organisational factors, such as bed occupancy rates, cleanliness and use of temporary staffing, to understand the variations in MRSA rates between different hospitals. The paper also examines how these relationships may have changed over time Hospital organisation, specialty mix and MRSA 17 September 2007 The possibility of transmitting infections via uniforms is an important issue for employers, staff and patients. This document outlines the existing legal requirements and current findings, to support and advise employers when reviewing local policies in this area Uniforms and workwear: an evidence base for developing local policy 11 April 2007 A web-based system for the surveillance of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea (CDAD) is being introduced in April 2007 and Trusts will have to enter all cases in individuals aged two years and over on to this new system (subject to Review of Central Returns (ROCR) approval). 2005 Winning Ways DIPC, Baord accountability Guidance • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • PL CMO (2007)4: Changes to the mandatory healthcare associated infection surveillance system for Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea from April 2007 A plan for action Towards cleaner hospitals and lower rates of infection and Winning ways are two key policy documents that set out a strategy to improve hospital cleanliness and tackle hospital acquired infections. A plan for action Towards cleaner hospitals and lower rates of infection programme Programme that sets out a strategy to improve hospital cleanliness and tackle healthcare associated infections. Key elements include empowering patients and the public, the matron's charter, independent inspection and learning from the best. Towards cleaner hospitals and lower rates of infection programme Simple guides Outline information on MRSA and Clostridium difficile A simple guide to MRSA A simple guide to Clostridium difficile Check infection rates at your local hospital Results of surveillance systems for MRSA, CDAD and GRE. MRSA surveillance system: Results Surveillance of surgical site infection in orthopaedic surgery: Mandatory surveillance of surgical site infection in orthopaedic surgery: Report of data collected between April 2004 and March 2005 Surveillance of Clostridium difficile associated disease (CDAD) Surveillance of glycopeptide-resistant enterococci (GRE) Healthcare associated infection publications Documents about healthcare associated infections, principally for health professionals. Healthcare associated infection publications Healthcare associated infection links Websites and DH resources about healthcare associated infections. Healthcare associated infection links Root cause analysis National Patient Safety Agency 1 2 3 The Patients Association and HCAI Infection control campaign • Since 2000, surveys and action on patient safety eg hand-washing; use of antibiotics; decontamination Reports • • • • • • • 2000 Hospital Acquired Infection and the Reuse of Medical Devices 2001 Decontamination of Surgical Instruments - implementation of HSC 2000/032. 2002 Role of SHAs in decontamination and safe medical devices 2004 Survey of HCW non-compliance in recommended uses of devices, endoscopes etc 2005 Tracking medical devices, implications for patient safety with ICNA etc . The Clean Hospital Summit - reducing HCAI and 100 Day Challenge, mandatory reporting and HCC standards 2006 Second summit Cleaner Hospitals, Safer Healthcare, to raise profile of IC. Infection Control –Is It Only Skin Deep? 2007 Supported epic2 guidelines for preventing HCAI The Patients Association's Ten Top Tips to using your Patient Power! Check Trust’s Annual Health check ratings October 2006 www.healthcarecommission.org.uk 2 Before planned admission take a long hot soapy bath or shower…to help prevent unwanted bacteria coming into hospital with you and complicating your care. 3 Pack antiseptic hand-wipes, bulldog clips & plastic bags for waste 4 Note & point out to staff messy/dirty areas 5 Arrange a “phone tree” with family and friends to save staff time 6 Ask visitors to co-ordinate visits and restrict to two at bedside (after bath or shower) 7 Ask visitors to use hand cleansers on arrival and departure 8 Discourage child visitors 9 Tell visitors not to sit on your bed and not to come if have URTI 10 Don’t be afraid to ask a nurse or a doctor whether they have washed their hands or used the disinfecting hand gel 1 Don’t be afraid to ask questions, especially about your own condition or to make valid complaints Select Committee on Science and Technology Seventh Report 1998 Comprehensive report on antibiotic resistance and its public health consequences, commissioned by the United Kingdom Parliament, Select Committee on Science CHAPTER 4 INFECTION CONTROL 4.1 As resistance to antimicrobials increases, so does the importance of infection control. Preventing the spread of organisms which are resistant and therefore hard to treat is obviously desirable. Less obvious, but equally desirable, is control of infection by organisms which are still susceptible; every infection not prevented requires treatment, and every treatment adds to the selective pressure towards resistance. Infection control in hospitals 4.2 In some respects, hospitals achieve the level of infection control for which they are willing or able to pay. Money can buy infection control in various ways, some of which are considered in the next few paragraphs. Standards of hospital infection control management in England and Wales were recently defined by the "Cooke Report"[45]; looking ahead, that Report said, "Antibiotic-resistant bacteria will almost certainly be an increasing problem [for hospital infection control] in the future". Infection control teams 4.3 According to the Cooke Report (ch. 2), every acute hospital should have an infection control team.[46] The team should consist of an infection control doctor (normally a consultant medical microbiologist) and one or more infection control nurses. Non-acute hospitals should be covered, under contract, by a team from a neighbouring acute hospital. Every hospital should also be covered by a multidisciplinary Hospital Infection Control Committee. 4.4 A recognised qualification for infection control doctors has been established (DipHIC). As for nurses, the Infection Control Nurses Association (ICNA)[47] told us, "The minimum recommended training requirement for infection control nurses is a post-basic diploma-level course in infection control and previous management experience...Most NHS trusts comply with this; however some private hospitals do not" (Q 201). Infection rates • • • • • DH monitoring rates Rates from incidents/outbreaks Measurable infection rates Interpretable infection rates Evidence Roles and responsibilities for action • • • • • • • Infection Control - providers Surveillance – providers, HPA Advice/support - HPA Performance management – SHA, DH (PCT) Investigation – Provider, HPA Management - Provider Working together - All Litigation £5m hospital bug payout for Ash Actress Leslie Ash has won a record £5m compensation payout after contracting a hospitalacquired infection. The Men Behaving Badly star developed MSSA (Methicillin-Sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus) at Chelsea and Westminster Hospital in London in 2004. The payment to Ms Ash, 47, who now walks with a stick, includes compensation for money she would have earned if she had carried on working. The hospital said it had "learnt from its mistakes". “It's the highest we have ever paid out” Ms Ash had been admitted to hospital in April 2004 after suffering two cracked ribs after falling off her bed on to a Steve Walker table during a love-making session with her husband, NHS Litigation Authority CEO retired footballer Lee Chapman US Patient Safety The Association for Professionals in Infection Control & Epidemiology Hospital-Acquired Infections Hospital-acquired infections are one of the top ten leading causes of death in the U.S. and significantly increase the cost of health care. reports that 1.2 million hospital patients are infected with dangerous, drugresistant staph infections each year. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in 20 patients – about two million a year – contract an infection while in the hospital. Hospital-acquired infections kill over 90,000 people annually – more than motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer, or AIDS. Hospital-acquired infections increase the length of hospital stays up to 30 days. The cost to the U.S. health system of treating hospitalized patients with staph infections is astronomical – between $3.2 billion to $4.2 billion a year. Learning from incidents/outbreaks • • • • • • • • SE – HCC MRSA C.diff Acinetobacter baumanii ESBL producing E .coli GRE TB Flu Lessons from incidents/outbreaks MRSA - Kettering Lessons from outbreaks Original article A major outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus caused by a new phage-type (EMRSA-16) R. A. Cox , C. Conquest, C. Mallaghan and R. R. Marples Abstract An outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection caused by a novel phage-type (now designated EMRSA-16) occurred in three hospitals in East Northamptonshire over a 21-month period (April 1991—December 1992). Four hundred patients were colonized or infected. Seven patients died as a direct result of infection. Chest infections were significantly associated with the outbreak strain when compared with methicillin-sensitive S. aureus. Twenty-seven staff and two relatives who cared for patients were also colonized. A ‘search and destroy’ strategy, as advocated in the current UK guidelines for control of epidemic MRSA was implemented after detection of the first case. Despite extensive screening of staff and patients and isolation of colonized and infected patients, the outbreak strain spread to all wards of the three hospitals except paediatrics and maternity. A high incidence of throat colonization (51%) was observed. Failure to recognize the importance of this until late in the outbreak contributed to the delay in containing its spread. Key parts of the strategy which eventually contained the local outbreak were the establishment of isolation wards in two hospitals, treatment of all colonized patients and staff to eradicate carriage and screening of all patients upon discharge from wards where MRSA had ever been detected. EMRSA-16 spread to neighbouring hospitals by early 1992 and to London and the South of England by 1993. It is distinguished from other epidemic strains by its characteristic phagetype, antibiogram (susceptibility to tetracycline and resistance to ciprofloxacin), and in the pattern given on pulse field electrophoresis. MRSA – past present and future • • • • • • • • • • • S .aureus treatable with Methicillin when introduced in 1960 Early methicillin resistance but not considered serious Isolation beds for management of infection used for other purposes Cohorting rather than isolation in major outbreaks EMRSA - (first major outbreak 1 in Australia) varying strains since have affected most UK hospitals National guidelines for control of MRSA 1998, 2005 High risk areas – IT, renal ~ los Colonisation/carriers Control of epidemics vs ‘search and destroy’ Antibiotic choice Research – need for well designed trials Newsom SWB. JRSM 2004; 97(11) 509-10. MRSA – past present and future • • • • ?? Endemic Antiseptic use eg tea tree oil Environmental decontamination – steam, hydrogen peroxide, Rapid diagnostics – Elisa, PCR • Govt manadates – deep cleaning, screening • Research – need for well designed trials • ??? Too little too late Lessons from outbreaks CDAD - SMH Clostridium difficile • Clostridium difficile is an anaerobic bacterium, widely distributed in soil and intestinal tracts of animals. The clinical spectrum of CDAD ranges from mild diarrhoea to severe life threatening pseudomembranous colitis. The disease is not always associated with previous antibiotic use. There is an increase of reports of community-acquired CDAD in individuals previously not recognized as predisposed. CDAD is also recognised increasingly in a variety of animal species. The transmission of C. difficile can be patient-to-patient, via contaminated hands of healthcare workers or by environmental contamination. • The impact of CDAD on modern healthcare is significant. In terms of costs, this translates into €5.000-15.000 per case in England and $1.1 billion per year in the USA. Assuming the population of European Union to be 457 million, CDAD can be estimated to potentially cost the Union €3.000 million per annum. It is expected to almost double over the next four decades. • Since March 2003, increasing rates of CDAD have been reported in Canada and USA with a more severe course, higher mortality, and more complications. This increased virulence is assumed to be associated with higher amounts of toxin production by fluoroquinolone-resistant strains belonging to PCR ribotype 027, toxinotype III and PFGE NAP1. Epidemics of CDAD due to the new, highly virulent strain of C. difficile PCR ribotype 027 have been recognized in 44 hospitals in England, 8 hospitals in the Netherlands and 6 hospitals in Belgium. Retrospectively, PCR ribotype 027 was shown to have already caused outbreaks in 2002 in all three countries. The outbreaks are very difficult to control. Preliminary results from case-control studies indicate a correlation with the use of fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins. No information is available on communityacquired cases of type 027. Data on the incidence of type 027 in nursing homes are limited, but at least one outbreak has been detected. ECDC CDAD definitions Severity Kuipjer et al 2006 Media coverage Healthcare Commission enquiry Recommendations (19) Recommendations Recommendations Grave failure of patient protection - change in leadership Actions by managers to control risk of infection 1-3 Infection control and training Standards of care 4-7 Clinical care, patient dignity, transfer, clinical decision dissemination Staffing 8 Levels and training for safe care Clinical governance and risk management 9-13 Clinical risk management including infection control Handling and learning from complaints 14 Serious complaint investigation and management responsibility of board National responsibilities 15-19 NHS, HPA, DH Epidemic curve and control SMH Acquired C.difficile Dec 03 - Feb 06 38 March 04: Removal of co-amoxiclav, amoxicillin, clindamycin, cephalosporins Use of hypochlorite disinfectant Creation of cohort area 36 34 32 30 28 March 05: Removal of ciprofloxacin Use of hydrogen peroxide vapour on a few wards Creation of a C.diff ward. 26 • Routine surveillance (lab) • Enhanced surveillance 24 • OCT 22 20 • Control measures 18 16 • Investigation 14 12 10 • Action plan 8 6 • Continuing vigilance 4 2 Au gu st Se pt em be r Oc tob er No ve mb er De ce mb er Ja n-0 6 Fe br ua ry Ju ly Ju ne Ma y Ap ri l Au gu st Se pt em be r Oc tob er No ve mb er De ce mb er Ja n-0 5 Fe br ua ry Ma rc h Ju ly Ju ne Ma y Ap ri l De c -0 3 Ja n-0 4 Fe br ua ry Ma rc h 0 Kindly provided by Dr J O’Driscoll, Consultant Medical Microbiologist, Buckinghamshire NHS Trust C. difficile in Bucks NHS Trust Outbreak one of several in UK • • • About 500 cases of CDAD since Dec 2003 at Bucks Hospital NHS Trust Oct 03 - June 04: 174 new cases, 19 deaths due to C.difficile infection, 16 SMH acquired Oct 04 – June 05: 160 new cases, 19 deaths due to C.difficile infection, 17 SMH acquired • • • Mortality higher than expected in infected patients >100 patients infected with C difficile died, 78 with C.difficile infection • Control measures contained problem summer 2004 and summer 2005 • Most recent cases biotype 027 (Canadian/American strain PulsoverA/BI) • 027 hypertoxin producing strain causing severe disease of prolonged duration • Resistant to antibiotic therapy C.difficile biotypes in SMH since Dec 2004 106 17 14 17 01 027 No of isolates tested = 60 Lessons from outbreaks The epidemiology of the second phase of an outbreak of Clostridium difficile associated diarrhoea (CDAD) at Stoke Mandeville Hospital Objectives To establish epidemiology of second phase of Stoke Mandeville Hospital (SMH) CDAD outbreak 1 Dec 04 - 31 May 05, and to document control measures. Methods 229 incident cases of CDAD and readmissions with positive isolates for both admissions to Bucks Hospitals NHS Trust included. Hospital acquired if symptoms > 3 days from admission. Relapse - 2 confirmed diagnoses > 3 months apart. Demographic and clinical information extracted from case notes. Autopsy findings extracted from pathology systems and infection control measures obtained from infection control records and clinical notes. LREC approval. Data analysis used STATA 8.2. Results • Incidence of CDAD at SMH was 2.11/1000 bed days and accounted 5312 bed days. Monthly incidence highest in winter months with January peak. • Most cases due to the 027 ribotype. • 88% of patients > 65 years of age • 60% female and 25% were community acquired. . • Mean LOS in hospital before symptoms 12.4 days, total mean LOS 48.8 days. • MRSA coinfection in 16.3%. • High ciprofloxacin use. • CDAD attributable mortality 15%. Conclusion Confirmed 027 ribotype as UK outbreak strain with high mortality and morbidity. Raised the national profile of CDAD. Applying the national additional hospital cost of £4000/ CDAD cost to NHS Trust about £900 000 over 6 months. Lessons from outbreaks CDAD - Maidstone Healthcare Commission enquiry Recommendations Significant failing on the part of the trust. 1. Action by the board - review leadership with performance manager of the trust the SHA taking overall responsibility for this 2. Clinical governance and the management of risk - control of infection an integral part of clinical governance 3. Action by board and managers to control the risk of infection - greater priority to the control of infection including effective isolation 4. Standards of care - diagnosis of C. difficile needs to be regarded as a diagnosis in its own right with care and treatment in line with good practice National responsibilities 5. Staffing levels and training - ensure acceptable and safe levels and training 6. National recommendations C. difficile- a diagnosis in its own right, - proper management as a potentially life threatening condition. - commissioners of care ensuring guidelines for prevention and management - education and supervision of trainee doctors, including death certification, ab use Recommendations Recommendations - antibiotics of the narrowest spectrum possible used for the shortest time possible. - NHS and HPA to agree clear and consistent arrangements for the monitoring of rates of C. difficile infection, using all relevant local and national information. - Every NHS trust to understand the role and responsibilities of the DIPC and receive regularly, information about incidence and HCAI trends Duty 2 of the hygiene code HCC and Leicester In early October 2006, contact was made between University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust and the Healthcare Commission regarding the high number of cases of the Clostridium difficile infection at the trust in 2005 and 2006. HCC agreed to explore the issue further with the trust to understand the arrangements and challenges in the management of Clostridium difficile infection, using the Government’s Hygiene Code as a framework for review. The main purpose of the review was to assess the trust’s arrangements for preventing and controlling of the infection. Lessons from outbreaks ESBL producing E.coli SE and London regions Case - control study Death analysis Southampton St Peters Ashford Infection rates – HPA publications HPA publications HCAI data HCAI data Infection rates – HPA publications Glycopeptide-Resistant Enterococcal (GRE) Bloodstream Infections HCAI data HCAI data HCAI data HCAI data HCAI data HCAI data Infection rates – HPA publications Clostridium difficile Infection rates – HPA publications Clostridium difficile Infection rates – HPA publications Clostridium difficile SE Data Programmes and comparisons • ECDC - Project on antimicrobial resistance and healthcare-associated infections • Nordic experience • N Am • Australia • UK Control measures • • • • • • IC + expertise DH/political Monitoring Improvement plan ?? Investigation Evidence What works • • • • • • • outcome – control of infection/colonisation how much can IC work? evaluation programme (place of screening/cleaning) plan learning from elsewhere evidence base HCAI: a balancing act Multiple players Targets Nat. service frameworks Culture, behaviour , practice Staffing levels Funding Bed availability Patient-centred NHS Thanks to Dr Barbara Bannister What next? Questions? Thank you