street law - Capital High School

advertisement

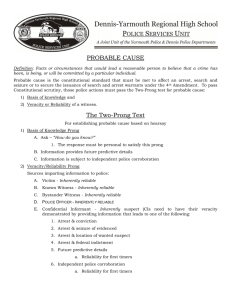

UNIT 2: Criminal Law and Juvenile Justice Chapter 12 Criminal Justice Process: The Investigation For my part I think it a less evil that some criminal should escape than that the government should The criminal justice process includes everything that happens to a person from the moment of arrest, through prosecution & conviction, to release from jail or prison This chapter deals with the investigation phase, which includes arrest, search & seizure, interrogations, and confessions – it also looks at how the U.S. Constitution limits what police can do There are separate state & federal criminal justice systems Sequence of Events in the Criminal Justice Process T12-1 [Handout] Page 135 Introduction Great discretion can be exercised by criminal justice system personnel at each step of the process from the police to the prosecutor to the sentencing judge to personnel in the correctional system Many of the most critical events of a case happen before the trial (i.e., at a pretrial hearing, when the defendant may attempt to suppress certain evidence), & relatively few cases actually result in a trial Many cases are either dropped or terminated by a plea bargain Once a crime is reported, an investigation follows If the investigation leads to an arrest, the case is said to have “cleared” Clearance rates are usually highest for the most serious crimes because police departments focus their resources on these cases Law Enforcement Models There is on-going tension between two competing law enforcement models: the crime control model & the due process model The crime control model emphasizes the apprehension & punishment of criminals The due process model emphasizes the use of fair procedures in dealing with defendants ○ A variation of this model is the fairness or due- process of victims model that focuses on justice for the victim Proponents of each model seek to reduce crime, but through different means Criminal Procedure Rights Granted by State Constitutions In WA, arrests based on information from informants require a credible informant and reliable information Arrest An arrest takes place when a person suspected of a crime is taken into custody An arrest is considered a seizure under the Fourth Amendment, which requires that seizures be reasonable The police may take someone into custody 1 of 2 ways W/O an arrest warrant in certain felony cases & in misdemeanor cases (in public) if there is probable cause With an arrest warrant ○ An arrest warrant is a court order commanding that the person named in it be taken into custody - it shows that a judge agrees there is probable cause for the arrest Probable cause to arrest means having a reasonable belief that a specific person has committed a crime To show probable cause, there must be some facts that connect the person to the crime This reasonable belief may be based on much less evidence than is necessary to prove a person guilty at trial The courts have allowed drug enforcement officials to use what is known as a drug courier profile Used to provide a basis to stop & question a person or to help establish probable cause for arrest Often based on commonly held notions concerning the typical age, race, personal appearance, behavior & mannerisms of drug couriers Opposition Individualized suspicion – as opposed to the generalized characteristics of drug couriers – should be required to establish probable cause Proponents Drug interdiction presents unique law enforcement problems & that the use of the profiles is necessary in order to stop drug trafficking Police may establish probable cause from info. provided by citizens Info. from victims or witnesses can be used to obtain an arrest warrant Info. from informants can also be used if they can convince the judge that the information is reliable Whether the informant has provided accurate info. in the past How the informant obtained the info., & Whether the police can corroborate (or confirm) the informant’s tip w/other info. If an officer has reasonable suspicion that the person is armed & dangerous, he may do a limited pat-down of the person’s outer clothing—called a stop & frisk—to remove any weapons the person may be carrying A police officer does not need probable cause to stop & question an individual on the street You may decline & continue your activity – your silence or departure may not contribute to probable cause or reasonable suspicion If you run from the officer, that flight may give the officer reasonable suspicion to stop you again, at this point you cannot walk away (especially in areas of high crime) However, the officer must have reasonable suspicion to believe the individual is involved in criminal activity The reasonable suspicion standard does not require as much evidence as probable cause – it must be more than a mere hunch Therefore, it is easier for police to stop & question a person than it is to arrest a person The most common kind of arrest is when people don’t realize they are being arrested at all If you are taken into custody under circumstances in which a reasonable person would not feel free to leave is considered to be under arrest - whether or not you are told that When an officer stops a person driving a car for violating traffic laws, the driver is technically under arrest because the driver isn’t free to leave, but must stay until the officer releases him or her In 1997, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that police can order all passengers out of a car when making a lawful traffic stop The detention in this case is brief, usually lasting only as long as it takes the officer to check ID & registration, & typically ends when a citation (ticket) is issued for the violation Probable Cause & the Law on Stops & Arrests * Reasonable Suspicion & Belief the Suspect Might Be Armed and Dangerous * * Reasonable Suspicion Arrest Stop & Frisk LEVEL OF INTRUSION: Stop * No Suspicions Consensual Encounter LEVEL OF PROOF Probable Cause Police Action What Is It? When Can Police Do It? Consensual Encounter An officer talks with an individual. The individual is free to leave at any time. An officer can do this at any time. No information is required prior to an informal contact. Example: An officer asks a pedestrian if she saw the person who broke a store window or the officer talks to a second-grade class about safety. Police Action What Is It? When Can Police Do It? A stop (also known as an investigative detention) A brief period of questioning during which no charges are made. The person is not free to leave at any time. If an officer, based on his or her experience, has a reasonable suspicion that a person is involved in a crime that is taking place or being planned, then the officer can stop the person to ask for identification and an explanation of the suspicious activity. Reasonable suspicion is more than a hunch and is based on specific details or facts. Police Action What Is It? When Can Police Do It? The person may be detained for a reasonable amount of time. One U.S. Supreme Court decision held that 20’ was reasonable. If the person if forced to go to a police station, courts have usually held that an arrest has taken place. Example: An officer sees a person pacing in front of a store window, picking up rocks, and looking up at the window. Police Action What Is It? When Can Police Do It? Stop and Frisk An officer “pats down” the outer garments of an individual to check for weapons in order to protect the officer’s safety In the case of Terry v. Ohio, the U.S. Supreme Court sanctioned stopping and frisking a suspect to search for weapons when there was reasonable suspicion that a crime was about to be committed and that the suspect might be armed and dangerous. Police Action What Is It? When Can Police Do It? If an item is felt during the frisk and the officer believes the item to be dangerous, the item will be taken, or seized. If the item taken provides the police with probable cause to arrest the person, the officer may then do a full search (such as pockets and socks) Police Action What Is It? When Can Police Do It? Arrest A person suspected of a crime is taken into custody. A person is not free to go and must remain with the police. An officer needs probable cause to make an arrest. Probable cause is the reasonable belief that a person has committed a crime. In some cases, prior to the arrest, officers must request an arrest warrant from a judge, who will determine whether there is probable cause to believe that the person named has committed the crime. In other cases, officers may not need a warrant. Example: An officer sees a person throw a rock through a store window Judges &/or juries determine if a defendant is convicted or acquitted—not police officers The level of proof required for criminal conviction is much higher than probable cause Convictions require that the accused be found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt The Use of Deadly Force - the 1985 U.S. Supreme Court case involving use of deadly force changed the law in many states In this case, a Memphis police officer shot a young person as he fled behind a house that the officer suspected him of burglarizing The officer did not know whether the youth was armed (he was not), but Tennessee law allowed use of deadly force if a suspect continued to flee after notice of intent to arrest The Court ruled this law, as well as the practice of using deadly force against people whom officers did not have probable cause to believe were dangerous, to be an illegal seizure under the 4th Amendment Even before the decision, a survey found that 87% of police departments allowed use of deadly force only against dangerous fleeing felons A police officer may use as much physical force as is reasonably necessary to make an arrest Most police departments limit the use of deadly force to incidents involving dangerous or threatening suspects In 1985, the U.S. Supreme Court was asked to decide whether it was lawful for police to shoot an “unarmed fleeing felony suspect” The Court ruled that deadly force “may not be used unless it is necessary to prevent escape, & the officer has probable cause to believe the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical harm to the officer or others” A police officer who uses too much force, makes an unlawful arrest or violates a citizen's rights can be sued under the federal Civil Rights Act The government could also file a criminal action against the police Many local governments have processes for handling citizen complaints against police misconduct A police officer is never liable for false arrest simply because the person arrested didn’t commit the crime It must be shown that the officer acted maliciously or had no reasonable grounds for suspicion of guilt If an arrest is later ruled unlawful, the evidence obtained as a result of the arrest may not be used against the accused Search and Seizure The 4th Amendment entitles each individual to be free from unreasonable searches & seizures & sets forth conditions under which search warrants may be issued In evaluating 4th Amendment cases, the courts seek to balance the government's need to gather evidence for law enforcement purposes against an individual's right to expect privacy Like other Bill of Rights protections, the right to privacy is not absolute Only “unreasonable” searches & seizures are prohibited The 4th Amendment protects people from the government & those acting with the authority of the government Search & Seizure law is complex – there are many exceptions to the basic rules Once an individual is arrested, it may be up to the courts to decide whether any evidence found in a search was legally obtained If a court finds that the search was unreasonable, then evidence found in the search cannot be used at the trial against the defendant This rule – the exclusionary rule – does not mean that the defendant cannot be tried or convicted, but it does mean that evidence seized in an unlawful search cannot be used at trial Traditionally, courts have found searches and seizures of private homes reasonable only when authorized by a valid search warrant A search warrant is a court order issued by a judge who agrees that the police have probable cause to conduct a search of a particular person or place However, there are many circumstances in which searches may be conducted without a warrant Cases that deal with warrantless searches are Maryland v. Buie, the “protective sweep case,” and Minnesota v. Dickerson, the “plain feel case” Even so, these searches must be reasonable under the 4th Amendment In analyzing search cases, it is helpful to ask: Did the person complaining of the search have a reasonable expectation of privacy in these circumstances? This approach helps explain why one’s privacy rights are usually greater in the home than on the street Recent U.S. Supreme Court decision have set out rules for police officers conducting searches when issuing traffic citations In one case, the Court ruled that a full search of a car belonging to a man stopped for speeding constituted an unreasonable search & invalidated the state law allowing such searches In another case of a man stopped for speeding, the Supreme Court upheld the officer’s full search of the car—in which drugs were found—because the driver consented to the search The Court refused to require that a defendant be advised that he or she is free to go before recognizing the consent as voluntary The Court also upheld a stop for a traffic violation that was a pretext for determining whether suspected drug crimes were being committed The stop was reasonable where the police had probable cause to believe that a traffic violation had occurred Then, when the officers observed drugs in the hands of one of the passengers, the search was considered a plain-view search The Supreme Court ruled that a police officer making a traffic stop may lawfully order the driver and all passengers out of a vehicle during the stop Recent cases have also explored the nature of the “knock and announce” rule, which requires officers to knock on the door & announce their identity & purpose before attempting a forcible entry The law usually requires that special reasons be given for permitting the search at night, between the hours of 10 pm & 6 am This lessens the chances that a search will be an unreasonable invasion of a citizen’s privacy Searches are generally limited to daylight hours to avoid the trauma of the “midnight knock” In addition, it may be more dangerous for police to execute search warrants at night If there is no response, the police may enter using force, if necessary Police may be excused from following the law under emergency circumstances For example—if the officer is genuinely in danger or contraband is being destroyed If a court finds that evidence was collected as the result of an unlawful search, the evidence cannot be used against the defendant at trial New Issues in Search & Seizure The examples in Problem 12.4 center on search & seizure of persons or physical items, but the 4th Amendment also applies to nonphysical information, such as phone conversations In 1967, a case went to the U.S. Supreme Court in which police intercepted conversations over a public telephone about illegal gambling activities The Court held that listening to & recording phone conversations with an electronic listening device attached to the outside of a public phone booth is a “search and seizure” subject to 4th Amendment protections, & a search warrant is required because a person has a reasonable expectation of privacy even when using a public phone Is it possible for police to conduct a search of your house that violates your 4th Amendment rights without ever entering your home or touching anything? As a result of modern technology and the Supreme Court’s decision in Kyllo v. United States, the answer is yes In the Kyllo case, federal agents were suspicious that marijuana was being grown in Danny Kyllo’s home & used a thermal imaging device to determine the amount of heat emanating from the house The amount of heat was consistent with the highintensity lamps that are often used for growing marijuana indoors The scan showed that Kyllo’s garage roof and a side wall were relatively hot compared to the rest of his home & substantially warmer than neighboring homes On the basis of this evidence, a judge issued a warrant to search Kyllo’s home, where agents found marijuana growing After he was indicted on a federal drug charge, Kyllo challenged the use of the thermal imager without a warrant as an unlawful search under the 4th Amendment This case raised new issues for the Court Under the expectation-of-privacy test, it could be argued that Kyllo had no expectation of privacy in the heat emanating from his home because he had done nothing to conceal it or keep it private However, under the circumstances this test seemed unfair Because Kyllo did not know that technology could allow detection of heat waves outside his home, he saw no reason to conceal them—he assumed his actions were private In a 5-4 decision authored by Judge Scalia, the Court agreed with Kyllo that a warrant is required if the government uses advanced technology that is not common in everyday use to obtain information about activities within a home or other settings for which the defendant has an expectation of privacy However, a warrant would not be necessary if officers used binoculars to see inside someone’s home, because binoculars are in common use The dissenting opinion argued that officers should be allowed to draw inferences from information that is available in the public domain, in this case heat waves The “Plain View” Exception The “plain-view” exception to the search warrant has been expanded to include plain hearing, plain smell, and plain feel Plain Hearing: allows officers to listen to conversations taking place in private areas where they have a right to be ○ For example—if officers can hear a conversation from a motel room next to one occupied by the suspects, they have a right to listen in Plain Smell: police may seize objects based on their odor when the odor establishes probable cause ○ For example—police can search for & seize marijuana based on the odor coming from a car Plain Feel: applies to situations in which a pat- down search immediately reveals the felt object is contraband or evidence of a crime Public School Searches In general, school officials are allowed to search students & their possessions without violating students‘ 4th Amendment rights Should the exclusionary rule apply to searches by school officials of students in high school? In the 1985 case, the state of New Jersey argued that the exclusionary rule should not apply to schools at all New Jersey argued that school officials were not agents of the state like police, who must follow the exclusionary rule Instead, they argued, school officials were standing in for the students’ parents (a doctrine called in loco parentis) & that the escalating problems of drugs & violence in the schools justified the exclusionary rule not being applied in school settings The Supreme Court rejected these arguments ○ It held that the rule should apply because students are citizens who should have the same basic rights as citizens on the street, although a lower standard of proof may be required ○ The court also ruled that public school officials were agents of the state New Jersey v. TLO How much evidence should a school official have before searching a student’s purse or locker? Should the standards of probable cause or reasonable suspicion be required? The Supreme Court ruled that the standard of probable cause required for searches outside school did not apply to school officials searching a student’s person or purse There has not been a Supreme Court ruling on searching student lockers, but most courts have allowed such searches by school officials on reasonable suspicion, which is less than probable cause These searches are usually on the basis that the lockers are owned by the school & that students do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in their public school lockers In this case, the Court ruled that the student, known as TLO, could be searched if the school official had, “reasonable grounds for suspecting that the search will turn up evidence that the student has violated, or is violating either the law or rules of the school” ○ Violating a “no smoking” rule can justify a search ○ Also, the exclusionary rule applies only to court proceedings ○ Even if evidence is illegally seized, it can be used against a student at a school disciplinary hearing The dissenting justices thought the normal probable cause standard should be required for school searches, & that the reasonable grounds standard constituted an inappropriate watering down of the 4th Amendment as it applied to schools Do you believe that the principal had the right to open the student’s purse? Could the marijuana & drug paraphernalia be used against her in court? In the actual case, the Supreme Court found that the fact that the student had been observed smoking in violation of school rules provided reasonable suspicion This justified the principal’s decision to open her purse & to look for cigarettes In addition, seeing the rolling papers in the purse gave rise to a reasonable suspicion that she possessed marijuana, which justified further search of the purse The dissenting justices argued that there was no need to open the purse because the teacher had observed the student smoking Even if the purse could be opened, once the cigarettes were found the principal had no right to look for other items [The general rule on searches of student property such as book bags & purses is that the principal or designee must have reasonable suspicion to start the search & the scope of the search must also be reasonable—it could be argued that upon finding cigarettes, it was reasonable for the principal to continue searching for matches or a lighter, which would help to determine whether or not this student had actually been smoking—in a lawful search, it is permissible to seize anything that is illegal to possess] Should HS students have fewer rights or the same rights as adults in the community? Some people argue that students’ rights should be restricted because of their age, lack of maturity, & the fact that schools are special places of learning that should not be compromised by the distractions that stem from problems such as drugs & violence Others argue that students cannot be taught the principles of the Constitution or other civic values if these principles do not apply to them as well They may also argue that if a school provides students fewer rights than adults, the message is that the rights of students are not important Drug Testing—Earls Prob. 12.7—The Case of Student Drug Testing In an opinion written by Justice Thomas, the majority held that individualized suspicion was not necessary in order to require drug testing of students participating in activities nor was a warrant required because public schools fall under the special needs exception The Court found that this was one of the limited circumstances, like a sobriety checkpoint to catch drunk drivers, in which the need to discover hidden conditions or prevent their development is sufficiently compelling to justify the privacy invasion Suspicionless Searches Searches & seizures are usually unreasonable if there is no individual suspicion of wrongdoing Ex: police can’t search all the people gathered at a street corner if they suspected that only 1 of the people possessed evidence of a crime They could search only the person upon whom their individual suspicion is focused so that the privacy rights of others are protected The U.S. Supreme Court has recognized some limited circumstances in which this requirement of individualized suspicion need not be met Ex: the Court has upheld suspicionless searches conducted in the context of a program designed to meet special needs beyond the goals of routine law enforcement ○ These special circumstances include fixed-point searches at or near borders to detect illegal aliens, & mandatory drug & alcohol tests for railroad employees who have been involved in accidents These searches are controversial because they seem to depart from the 4th Amendment’s explicit requirement that searches be based on probable cause Racial Profiling in Police Investigations Complaints of racial profiling have increased in recent years Racial profiling – or racially biased policing – is the inappropriate use of race as a factor in identifying people who may break or have broken the law Critics say that it violates people’s constitutional right to equal protection before the law & presumption of innocence They also say that it is an ineffective law enforcement tactic it reinforces racial stereotypes in society & it creates negative relations between police & citizens The general rule is that it is inappropriate for an officer to stop a person solely because of his/her race Race may be used as one factor among others in deciding whom to stop ○ Ex: an eyewitness describes the robber as an African American man – police may use race as a factor in deciding to stop an African American man that is seen running from the immediate vicinity Much of the racial profiling centers of traffic stops—known in the African American community as DWB—or “driving while black” In 1998, a federal judge reduced an African American defendant’s criminal sentence on the grounds that his lengthy prior record may have been skewered by race-based traffic stops As a result of Wilkins v. Maryland State Police, many studies on racial profiling were conducted throughout the U.S., with alarming results . . . One analysis of police searches along I-95 (N from FL to Maine) revealed that although 74.4% of speeders were white, African Americans constituted 79.2% of the drivers searched Another investigation in NY in 1999 revealed that African Americans were stopped 6 times more often than whites—African Americans were only 25% of the NY population, yet made up 50% of the people stopped & 67% of the people stopped by the NYC Street Crimes Unit After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, many Arab Americans, people of Middle Eastern descent, Muslims, & people who simply “looked Arab” complained that they were being detained or questioned by police or by security guards at airports for no reason other than their appearance, clothing, or because they were carrying a religious symbol or book The law prohibits racial profiling, as it requires that most stops, arrests, & searches made by police officers be based on some sort of individualized suspicion However, it is sometimes difficult to prove why a police officer stopped or arrested a person As of 2002, 14 states had passed legislation mandating racial profiling policies, & more than 400 law enforcement agencies have instituted data-collection methods to learn more about the actual extent of the problem Despite the fact that racial profiling is against the law & that most people say they are against the practice, some minority groups & civil liberties organizations feel that the problem continues to occur & needs to be controlled According to a 2002 report issued by the Office of Community Oriented Policing > 60% of Americans believe racial profiling exists Other people feel that it is reasonable, in light of the September 11, 2001 attacks, or in neighborhoods with a high rate of crimes by individuals of a certain racial or ethnic group, to search people solely because of their race Interrogations and Confessions Miranda Warnings: You have the right to . . . Recent cases have altered the original effect of the Miranda case In one case, the Court held that police may ask questions related to public safety before advising suspects of their rights The Court also limited the impact of the Miranda ruling by requiring that the person be in a condition of custodial interrogation before the Miranda warnings are needed Custodial Interrogation and Confession Law The law in the area of interrogations & confessions is widely misunderstood—many people think that Miranda warnings must be given at the time of arrest or the case will be thrown out While Miranda warnings often are given at this point, they are not a requirement of a lawful arrest They are required once a defendant is in custody or otherwise deprived of his or her freedom in some significant way & is being interrogated After an arrest is made, it is standard police practice to ?, or interrogate, the accused These interrogations often result in confessions or admissions The accused’s confessions or admissions are later used as evidence at trial Balanced against the police’s need to ? suspects are the constitutional rights of people accused of a crime The 5th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides citizens with a privilege against self-incrimination ○ This means that a suspect has a right to remain silent & can’t be forced to testify against himself/herself ○ This protection rests on a basic legal principle: the government bears the burden of proof ○ Suspects are not obliged to help the gov. prove they committed a crime or to testify at their own trial Under the 6th Amendment, a person accused of a crime has the right to the assistance of an attorney The U.S. Supreme Court has held that a confession is not admissible as evidence if it is not voluntary & trustworthy This means that using physical force, torture, threats, or other techniques that could force an innocent person to confess is prohibited In the case of Escobedo v. Illinois, the Supreme Court said that even a voluntary confession is inadmissible as evidence if it is obtained after the defendant’s request to talk with an attorney has been denied The Court reasoned that the presence of Escobedo’s attorney could have helped him avoid self-incrimination Although some defendants might ask for an attorney, others might not be aware of or understand their right to remain silent or their right to have a lawyer present during questioning In 1966, the Supreme Court was presented with such a situation in the case of Miranda v. Arizona In it’s decision, the Supreme Court ruled that Ernesto Miranda’s confession could not be used at trial because officers had obtained it without informing Miranda of his right to a lawyer & his right to remain silent As a result of this case, police are now required to inform people taken into custody of the so-called Miranda rights before questioning begins This taking into custody might actually precede an officer’s statement - “You’re under arrest!” The key issue is: When did custodial interrogation begin? In any case, giving or not giving the Miranda warnings is not related to the validity of the arrest If the warnings are not given, the arrest itself is still considered valid if it is supported by probable cause, but the state will not be able to use any illegally obtained confession against the defendant at the trial Depending on other evidence that the state has, this could— but not necessarily—result in charges being dropped In Miranda’s 2nd trial, even though the court couldn’t use his confession as evidence against him, Miranda was convicted based on other evidence In Standbury v. California, the U.S. Supreme Court further explained what is meant by custodial interrogation The fact that the officer questioning an individual believes that the person is a suspect does not mean that the suspect is in custody unless that fact is communicated to the suspect In other words, if during questioning, an officer begins to suspect the person of a crime but does not tell the person, then a reasonable person would feel he or she was free to leave, & therefore not in custody In a 1980 case, a robbery suspect was given the Miranda warnings several times & replied that he wanted to consult a lawyer On the way to the police station, one officer said to the another that he was afraid a missing shotgun (believed to have been used in the robbery) would be found by a student from a nearby school The other officer made similar comments Overhearing, the defendant then said he would show them where the gun was located The U.S. Supreme Court held that the police comments were “offhand remarks” & not an interrogation that the officers would have expected to evoke an incriminating response The Supreme Court has also held that the Miranda case does not apply to a police officer stopping a motorist suspected of driving while intoxicated The Court said that no Miranda warnings need to be given until the person is “in custody” (in a condition of “custodial interrogation” before the warnings are needed) Custodial interrogation means that the person is in custody (not free to leave) & is being interrogated (questioned) by the police The case of New York v. Quarles created a public safety exception to Miranda A police officer who was arresting a rape suspect in a grocery store asked the suspect where his gun was before advising him of his rights The suspect then pointed to a nearby grocery counter, where the gun was found The court held that police may ask ?’s related to public safety before advising suspects of their rights Miranda warnings also need not be given in the exact form described in the Miranda case This interpretation of the Miranda decision occurred in the 1989 case Duckworth v. Eagan The defendant was informed that if he could not afford a lawyer, one would be appointed “if and when you go to court” The Supreme Court held that this form of the Miranda warnings was adequate because it conveyed the necessary information to the defendant Remember that defense counsel will ask the judge before trial to exclude the results of an illegal search Defense counsel will also ask the judge at a pretrial hearing to exclude any statement given by the defendant in violation of the Miranda rule