Central Park Paper

advertisement

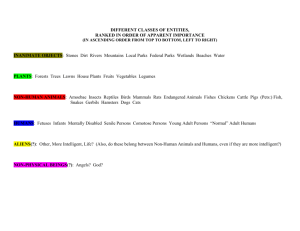

At it’s conception, Central Park was an unprecedentedly ambitious project; it was intended to elevate New York City’s international status to rival those of the great European cities as well as function as a respite for the urban masses. At 843 acres Central Park’s size alone indicates how massive an undertaking it must have been to create (not to mention maintain), designating it as one of the largest public works in New York City aside from the water and transportation systems. But how well does having a massive park situated in the middle of Manhattan work, and is it worth the efforts that have gone into sustaining it? The answer to this question is debatable. Certainly, utility is the central factor in evaluating the success of a public work, and the utility of Central Park is not as clearly evident as that of many other public works are (some examples of more obviously utilitarian works are the water and transportation systems mentioned above). While a near universal agreement can be reached that systems for transporting heat, light, water and people are necessary for a metropolis to function properly, the need for parks is a more dubious one. Though compelling theoretical arguments can be made casting Central Park (and large urban parks in general) as an example of either poor or good urban planning, the ultimate indicator of a public work’s success are the benefits it provides the public and the environment minus it’s costs to them. From this point onward, this paper will operate under the assumption that Central Park is intended as, first and foremost, a public work; all other purposes it may serve, such as a public art installation, are secondary. The primary objective of a public work is to cater to the needs of the greater public, and so the success of a public work may be evaluated by how well it does this. The issue with this standard is that the needs of the public shift due to continual development of new advances and challenges. The ability of a public work to meet these frequently changing requirements is often dependent on what those particular requirements are; thus, the successfulness of a public work is dependent on the context it exists in and can vary as the area and people surrounding change. Thus, the success of a public work lies not only upon it’s ability to satisfy the needs of the generation whom construct it but upon the construct’s ability to be adapted to the (possibly very different) needs of future generations. This paper will also argue that, as evidenced by Cranz’s typologies, we have entered the era of the ‘sustainable park’.i Thus, in our increasingly environmentallyconscious world, utility is defined not only by the amount of users per unit of space but by the space’s impact on the environment. Given that we now know that the condition planet has great bearing on the future good the public, the mission of today’s parks must be not only what they can provide for the public directly, but what they can do for the environment within which the public resides. Central Park’s current state cannot be fully understood, and I would argue fully evaluated, without an analysis of it’s past. Since the park’s success is contingent on it’s utility for the public, an analysis of the public relationship with Central Park is also necessitated. This paper will trace both, and through this discern how Central Park’s utility has changed (for better or worse) since its inception. Since the definition of success previously defined in regards to this paper essentially equates utilization to success, this measurement of utilization will also function as an indicator of the Park’s varying levels of success throughout time, allow for an evaluation of the park’s current level of success and speculate on it’s prospects for the future. Through the methods of evaluation described above, it can be concluded that though some admirable attempts have been made to adapt the park to address current issues, the successes have not been large enough to allow the park to be considered successful overall. Despite modifications during various eras to make Central Park more similar to whatever ideal existed for parks at the time, Central Park’s design is firmly grounded in an outdated Picturesque mindset, and it’s infrastructure is too inflexible to fully adapt it to the needs of today’s public and today’s environment. Unless Central Park undergoes a transformation in which it deviates greatly from Frederick law Olmstead’s initial design, it’s utility will never be fully realized. It should be noted that this is not an argument that Central Park has no utility, as this can be easily disproven by the myriad benefits it presents to millions of park-goers. Rather, this is an argument that Central Park is not utilized to it’s fullest potential, and that it has the capacity to offer even more benefits to more people as well as the environment than it currently does. In the article Defining the Sustainable Park: A Fifth Model For Urban Parks, Galen Cranz and Michael Boland identify five different types of urban parks: the pleasure ground, the reform park, the recreation facility, the open space system and the sustainable park. With the possible exception of the last two categories, the types are each assigned an era and follow each other chronologically with minimal overlap. This progression in park types is presumably an attempt to adapt to the public’s requirements. Reflective of it’s time of conception, Cranz and Boland designate Central Park as a ‘pleasure ground’. In 1857, the time during which construction of the park started, the nascent American landscape movement was beginning to gain prevalence and the idea of establishing grand public parks had begun to gain traction, particularly among elites. The winning design for New York’s grand park (what eventually became Central Park), the Greensward Plan, was heavily influenced by the pastoral ideals popular at the time. Due to this, Central park exhibits traits such as “curvilinear circulation and naturalistic use of trees and water”1; not coincidentally, these pastoral traits are also traits that Cranz and Bolan attribute to ‘pleasure grounds’. The pastoral vision in vogue at the time that most ‘pleasure grounds’ such as Central park was built, necessitates many of the features common to these ‘pleasure grounds’; for example, a park must be of sufficiently large size and/or of remote enough location (i.e. the outskirts of a city) so that the illusion of the nature is not undermined by the happenings of the city. Furthermore, the assumption of the pastoral ideal is that such natural settings provide respite from the city and therefore such a movement assumes that the city is something people need a respite from. It is this attempt to act as an antidote to the city that inspires many of the pastoral ideals urges to mimic nature and act as a direct contrast to the rest of city rather than as an incorporated piece of it. The money and land required for Central Park was justified by its proponents by the great good it was supposed to do the population of the city. In a time where miasma theory was widely accepted Central Park was meant to function as the lungs of the increasingly congested and polluted city, ameliorating the health-related woes of urbanization faced by city residents by bringing them into contact with nature. In this respect, Central Park’s size was justified by the largeness of its intended audience; the park was built with the intention of providing benefits to all city residents regardless of class. However, many authors, including Cranz and Boland, have contended that the number of actual beneficiaries is far smaller than the originally intended number. In reality, due to a lack of free time as well as limited modes of transport amongst the working class, the park remained relatively inaccessible to these groups and became mostly the domain of the wealthy or upper middle classes. Though intended (at least outwardly) as a gesture of equality, usage of the park was heavily correlated to socioeconomic status. It can be concluded from this that Central Park was, at the time, not a successful park. This lack of success can be largely attributed to the park’s design and the priorities of those with influence and power. Olmstead sought to better the lives of city dwellers by creating a insular countryside within the city. Olmstead succeeded in creating this selfcontained idyll, but his emphasis on this aspect of park development led him to disregard other aspects that may have appealed to the public and Central Park became what Matthew Gandy called an ‘elite playground for the wealthy’. Furthermore, current day priorities such as the facilitation of physical activity and sustainable practices were not even being contemplated at the time in which the park was coming to fruition; as a result, Central Park was not made with these considerations in mind and is ill-equipped to address these issues as they come up. Central Park’s status as a Pleasure Ground does not bode well for it’s current or future utility. Considering that the model offered limited utility even at the height of it’s popularity, it’s possibility of success in circumstances that require increasingly efficient parks are low. If beautification were the primary objective of the parks, then Central Park would be the epitome of success; however, in this case beauty is outweighed by a determination to increase efficiency and sustainability. While beauty is not irrelevant in public works, it has taken an increasingly smaller role as planners determine what the public and environment need. At first glance, the numbers would indicate that Central Park is heavily utilized; indeed, 8 to 9 million individual visitors each year is a massive quantity of people. It must be remembered that this large number is for a large park; Central Park’s success, as measured by users per acre, is tantamount to a 1 acre park that received a little over 90 individual visitors annually. While 90 visitors a year is still a respectable number, successful utilization is based not only on the number of users, but on who is a park user and what they use the park for. In is outline of what makes a park system excellent, Peter Harnik posits that parks should be “sited in a way in which every neighborhood and every resident are equitably served”. This is not true of Central Park, which is situated on an island that is also the richest borough of the city. While technically easily accessible via subway, in reality the length of commute is a deterrent for most outer borough residents, as indicated in the charts below. Furthermore, all parts of the park are not equally utilized. As the chart below shows, the vast majority of park activity takes place in the lower half of the park. While there may be many possible explanations for this, this large gap in usership indicates some sort of failure on the part of the Northern Park. The Northern Park’s relative under-usage may stem from a few issues. For people coming from other boroughs (with the exception of the Bronx), the Southern End of the park is easier to get to. Residents of Harlem may have less time to spend at the park than their counterparts on the Upper East and Upper West sides. The upper park may be viewed as unsafe due to the lack of park-goers there and this image may be selfperpetuating. The upper park may not offer the goods or services that the public desires. Regardless of cause, this inequitable distribution of activity inhibits park usage, by making some areas seem deserted and others overcrowded. This inconsistency amongst geographical areas correlates with a lack of equality amongst park users. Parks generally receive the most usage from those who reside in bordering neighborhoods, and the neighborhoods that border the lower park are generally upper middle class and wealthy. For example, the chart below shows that users of Central Park are mostly white, despite the high number of minorities in New York City and the fact that the upper park also borders Harlem, and area that has historically been home to a large Black population. The site of the park is also unhelpful for those looking to navigate Manhattan efficiently. Due to few subway and bus lines running through the park, the park acts as a barrier for many between Manhattan’s east and west sides and to a lesser extent it’s Northern and Southern halves. In this sense, the park not only lacks utility for many segments of the population but acts as an inconveniencing force. Academic commentary on the topic implies that these pitfalls are best avoided by the creation of many small parks as opposed to a few large ones. In this case, many neighborhoods instead of a few border parks. This means that more people would live closer, and therefore have better access, to parks. It would also eliminate the issue of middle space that goes unused due to it’s inaccessibility. Central Park however, cannot be cut up and redistributed throughout the city to facilitate higher rates of park usage amongst city residents and so it exists as a dinosaur (both in age and size) of the parks system. The second way in which to measure a park’s utility is in it’s utility for the environment. Since it is in the public interest to not damage the environment we depend on, the parks we create must try not to do this either. This realization has led to the increasing popularity of sustainable parks. To be successful, parks must also have what Harnik terms “external benefits” that will provide “ecological services” to the city. Cranz and Boland identify three main principles that distinguish sustainable parks from their predecessors: resource self-sufficiency, their status as an integrated part of a larger urban system and their aesthetic expression. Cranz and Boland write that traditional urban parks are not self-sufficient and cite this as one of the main causes of Central Park’s decline. Olmstead’s attempt to mimic nature only aesthetically and without it’s original “species composition or ecological function” resulted in the creation of a landscape that was largely non-native and nonregenerating. Without human intervention, much of Central Park fell into ecological disrepair and the woodlands were monopolized by invasive species such as Norway Maple and Japanese Knotweed. (Cramer 1993, 106) pg.106 This is not say that there has been no success in applying sustainable practices to Central Park. The park has undertaken many projects to increase sustainability, such as the conversion of the woodlands and marshlands into primarily native species, the leaf composting program and the implementation of the zone-gardener volunteer program (107/108). While these programs are laudable, it should be noted that they have high transaction costs and represent only a portion of the work that would need to be done to make the park wholly sustainable. Central Park may be becoming more successful, but the upkeep of it’s picturesque design requires a great deal of maintenance and environmentally-unfriendly resources such as herbicides, fertilizers and daily mowing. (109). Though these programs also increase civic engagement, Central Park will never be fully integrated into the city that way later models such as the open space system have been. The inherent design of the Pleasure Ground as a means of escape creates a dichotomy between nature and the city, facilitating a mental dissociation of our actions from the effects they produce that is detrimental to both the public and the environment. Aside from separating it from the rest of the city, the formality of Central Park does not easily lend itself to aesthetic or scientific exploration. Whereas the idea of parks as displays of ecological processes is gaining traction amongst today’s landscape architecture community, Central Park is centered around manicured meadows and plazas. The New York City Parks Department’s Sustainability Agenda offers a variety of ideas and pledges committing itself to becoming more sustainable. They cite multiple recently constructed parks as examples of their progress. But none of these parks are Central Park, and none of them even remotely resemble Central Park. These parks exemplify all the things that Central Park is not, from their high-tech playgrounds to the reclaimed brownfields which they occupy. Indeed, a premier focus of the Parks Department, and it seems urban environmental movements in general, is inserting green throughout the city via small parks, street trees and green roofs. But moves made towards this more integrated approach are also moves away from the ideals on which the Olmstead parks were founded, and the place of gargantuan gardens in this new vision is unclear. Environmentally speaking, Central Park is something that must be worked with because it already exists, but it is not something that should be emulated in future parks. That Central Park is a challenging component to incorporate into the Parks Department’s new sustainability agenda indicates it’s environmental inadequacy. In conclusion, Central Park’s origins as a Pleasure Ground undermine it’s ability to adapt to the needs of the public and the environment. Attempts to update the park have not done enough to ameliorate the lack of equitable access to the park or offset it’s environmental impact. In an era where park ideals are embodied by the “open space system” and/or “sustainable park” models, Central Park lacks relevancy. As public priorities shift, Central Park’s mission and design seem increasingly antiquated and it’s utility pales in comparison to more modern parks designed to promote equitable access and sustainability. This inability to efficiently provide for the public and the environment make Central Park an unsuccessful, even if beautiful, public work. Bibliography 1. Harnik, Peter (Platt, R. ed.) 2006. Humane Metropolis. The Excellent City Park System: What makes it great and how to get it there. 2. Hough, Michael (Platt, R. ed.). 1994. The Ecological City. Design with City Nature: An Overview of Some Issues. 3. Cranz, Galen and Michael Boland. 2004. Defining the Sustainable Park: A Fifth Model for Urban Parks. Landscape Journal. 23/2/04 4. Central Park Conservancy. 2011. Report On The Use Of Central Park 4/11 5. New York City Parks Dept. 2011 A Plan for Sustainable Practices within New York City Parks