Operations Strategy

advertisement

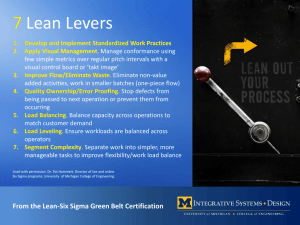

MD375 Operations Strategy & Consulting Class Notes Fall 2010 Professor Field Definitions of Operations Strategy An operations strategy is a set of goals, policies, and selfimposed restrictions that together describe how the organization proposes to direct and develop all the resources invested in operations so as to best fulfill its mission. Other definitions of operations strategy: An operations strategy consists of a pattern of decisions that, over time, enables a business unit to achieve a desired operations structure, infrastructure, and set of specific capabilities in support of competitive priorities. An operations strategy is a set of policies in both process choice and infrastructure design that are consistent with the existing ways products win orders, while being able to reflect future developments in line with changing business needs. The successful implementation of an operations strategy creates value for the customer. 2 Levels of Strategy Fin HR Corporate What business are we in? Divisional (business) How do we compete? Mkt Prod Devpt Ops Role of each function? 3 Components of the Definition Structural decision categories: Capacity Facilities Vertical integration (sourcing) Information/process technology Infrastructural decision categories: Capabilities: Unique to each firm Competitive priorities: Cost Quality Delivery Flexibility Innovation Workforce Organization Control/quality systems 4 Key Operations Principles Aggregation Principle Uncertainty Principle The higher the level of aggregation of resources and information, the more predictable operations becomes (e.g. forecasts of total product volume tend to be more accurate than forecasts of individual products). This is a manifestation of the Central Limit Theorem. The more uncertainty in operations, the greater the need to employ extra resources to cope with this uncertainty. Alternatively, the greater the stability and predictability, the leaner operations can function. Efficiency Principle All else being equal, operations should function as efficiently as possible. 5 Competitive Priorities Quality Quality consists of many dimensions that can be aggregated into: relative quality (level of attributes) and functional quality (the ability to operate as intended). The categories, dimensions, and definitions of quality are as follows: Relative Quality: Performance Features The "bells and whistles" of products and services, those characteristics that supplement their basic functioning Aesthetics A product's or service's primary operating characteristics How a product looks, feels, sounds, tastes, or smells For services – physical facilities, equipment, and appearance of personnel Perceived quality Inferences about quality based on indirect tangible and intangible aspects of the product or service (e.g. reputation) 6 Competitive Priorities Quality (cont.) Functional quality: Reliability Conformance The degree to which product or service design and operating characteristics meet established standards Durability The probability of a product malfunctioning or failing within a specified time period For services – ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately The amount of use one gets from a product or service before it deteriorates Service delivery The speed, courtesy, and competence of personnel For products – also, the ease of repair Improvements in functional quality result from a reduction in process variation. 7 Competitive Priorities Delivery Two delivery dimensions: Lead time The time the customer must wait between order placement and receipt Reliability How reliable the company is in delivering a customer's order on or before the quoted delivery date Both lead time and reliability can be improved by reducing uncertainty in the operations system. 8 Competitive Priorities Flexibility Primary flexibility dimensions: Product flexibility The ability to produce a wide variety of products or services and the ease with which the product or service mix can be changed Volume flexibility The ability of the production system to operate at different volumes and the ease with which the volume can be changed Increased flexibility is a means to deal with demand uncertainty. Advances in technology have greatly increased operational flexibility. 9 Competitive Priorities Innovation In operations, innovation as a competitive priority involves the ability to quickly introduce and improve process technologies, which increases speed to market with often better products and services. Main types of operations innovations: Incremental Minor improvements or simple adjustments in existing technology. Rapid accumulation of these innovations can convey a competitive advantage. Radical Fundamental changes that represent revolutionary changes in technology. They represent clear departures from existing practice (i.e., substantially new processes and process technologies) Innovation is often the primary competitive priority in high-velocity environments with short product life cycles. 10 Operations Strategy Formulation Content Mission Objectives Structural and infrastructural decisions are stated in strategic terms. They must be formulated to support the operations mission and objectives and should be consistent with each other and with what is intended to be accomplished by operations. Policies Operations objectives should be defined in concise, measurable terms, as part of the operations strategy. They should be specific statements of expected results – a refinement of the mission. Operational strategies The operations mission specifies what operations must accomplish for the business to succeed. It states the purpose of the operations function and competitive priorities as they relate to the customer and competition. Structural and infrastructural decisions are stated in tactical terms in support of the operational strategies. Distinctive competence The competitive priorities provide a framework for developing a distinctive competence, which is realized through the implementation of the operations strategy and the use of the firm’s resources. It is what sets operations apart from the competition and, thus, can be defined in terms of uniqueness. 11 A Marketing-Oriented View of Operations Strategy Development of an operations strategy: Define corporate objectives. Determine marketing strategies to meet these objectives. Assess how different products or services qualify in their respective markets and win orders against competitors. Establish the most appropriate process to produce or deliver these products or services (structural/infrastructural decisions). Provide the operations infrastructure to support production and delivery. The last two steps constitute the operations strategy. 12 Order Qualifiers and Order Winners Order-qualifiers are those criteria that a company must meet for a customer to even consider it as a possible supplier. Companies need only be as good as competitors. Order-winners are those criteria that win the order. Companies need to be better than their competitors. From an operations perspective, determining orderwinners and order qualifiers helps to define competitive priorities. This view of operations strategy is especially time- and market-specific. 13 Important Considerations in Operations Strategy Formulation Operations are part of a system that includes the other functional areas, the business, and the corporation. As such, the strategies must be linked, integrated, and mutually supportive. The operations strategy process is iterative, both within a planning cycle and between cycles. Between planning cycles, the operations strategy process should reflect the changing environment. While strategic planning precedes implementation, a plan that is not implemented is not a strategy and is often worse for the organization than no stated plan at all. 14 McDonald’s Example McDonald’s operations mission: McDonald’s operational strategies (structural): Capacity Facilities Distributed facilities, each facility being very similar to the next, all focused around a similar menu with some local variations (especially by country) Vertical integration (sourcing) Growth as needed through additional stores - but capacity added carefully Well-utilized - franchisee's well-being depends on heavily utilization Partnership arrangement Long-term relationship with suppliers to promote innovation and quality improvement Information/process technology High degree of process understanding, emphasis on "fool-proof" processes A leader in the technology of fast-food delivery 15 McDonald’s Example (cont.) McDonald’s operational strategies (infrastructural): Workforce Organization Franchisees: well-trained, carefully selected, entrepreneurs Operators: high-turnover, lower-paid Guidelines provided by corporation, but franchisees push to locally optimize Control/quality systems Centralized buying Bulk contracts "Push" system for basic supplies, "pull" system day-to-day in the restaurants 16 Criteria for Evaluating an Operations Strategy Consistency (internal and external): Between the operations strategy and the overall business strategy Among the decision categories that make up the operations strategy Between the operations strategy and the other functions’ strategies Between the operations strategy and the business environment (resources available, competitive behavior, governmental restraints, etc.) Contribution (to competitive advantage): Making trade-offs explicit, enabling operations to set priorities that enhance the competitive advantage Directing attention to opportunities that complement the business strategy Promoting clarity regarding the operations strategy throughout the firm Providing the operational capabilities that will be required by the business now and in the future 17 Evolution of Operations Strategy Stages Internally Neutral (Stage 1) Externally Neutral (Stage 2) Achieve parity with competitors. Internally Supportive (Stage 3) Minimize operation's negative potential. Provide credible support to the business. Externally Supportive (Stage 4) Pursue an operations-based competitive advantage. 18 Stages of Operations Strategy Stages 1 and 2 Internally neutral Operations not involved in strategy Keep operations under control - detailed measurement Fight fires, eliminate problems Operations is kept flexible and unfocused Short-term performance is emphasized Top management is not involved in operations Externally neutral Industry practice is followed Capital investment to maintain or gain position Keep up with competition in operations Planning horizon is one business cycle Use industry-wide wage rates 19 Stages of Operations Strategy Stages 3 and 4 Internally supportive An operations strategy is formulated and pursued Keep operations in step with business strategy Operations investments are screened for consistency with business strategy Longer-term trends are addressed systematically Consistency within operations Translate business strategy into operations terms Externally supportive Anticipate new operations practices and technology Operations is an equal partner in business strategy Operations is involved upfront in market decisions Operations contributes to other functions Structure and infrastructure are concerns to top management Teamwork and involved workforce Operations is innovative Competitive strategy rests on operations capability Functions of the firm are well integrated 20 Attacking and Defending through Operations Attacking: Positioning Appealing to a different customer need Capabilities Being better at the same game Process-based capabilities Systems (coordination)-based capabilities Organization-based capabilities Defending: Exploiting its own strengths Attacking its attacker’s operations-based weaknesses Recognizing the seriousness of the attack quickly and emulating the attacker’s strategy 21 Information-Intensive Industries and E-Commerce Characteristics and Implications for Operations Characteristics: The cost structure for most information-intensive products is dominated by the “upfront” costs associated with developing a new product and creating its associated production/delivery facilities. Rapid changes in technology and markets. Network effects (i.e. the increasing attractiveness to users of certain networks as they increase in size). Network effects are a function of the number of users of a particular technology and the system of complementary products associated with the network. Quality and time have an interaction effect. Information technology enables direct, real-time communication with users. Compatibility is as important as differentiation. Implications: Increased importance of project management. Cumulative output and speed to market are key for low-cost strategies. Installing a less-than-perfect but improvable system is sometimes better than waiting to introduce a more refined system later. High flexibility (customization) is at least an order qualifier. Operations must be able to introduce new products and services rapidly. Operations organized for collaboration and communication. 22 Issues in Service Operations Simultaneous production and consumption: Inability to inventory the customer-facing portion of services increases the importance of capacity and facilities management Services tend to be high on experience and credence attributes, and, Much of the service delivery process is transparent to the customer, therefore … Evaluation of the service is based to a large extent on the process and not just the outcome Because both the provider and customer are involved in service delivery process (i.e., co-production), effective service delivery requires that service delivery “models” or “scripts” are consistent between the customer and service provider. 23 Issues in Service Operations (cont.) Customer contact: The interaction between the front-line employee and customer is an important determinant of customer satisfaction, therefore … Greater variability (both complexity and divergence) in outcomes exists due to customer participation in service delivery, therefore … A high degree of customer contact requires that the interface between the service provider and customer be carefully managed. As the customer becomes more actively involved in the service process, it becomes increasingly difficult to deliver the service efficiently. Even a service that can be characterized as “high customer contact” overall is usually a mix of high and low contact. High and low contact segments of the service can be decoupled for greater efficiency, but should not always be decoupled. 24 Customer Contact Model 1 Potential facility efficiency customer contact Most services are a combination of high and low contact and can be designed for both customer satisfaction and efficiency by following these steps: Identify those points in the service system where decoupling between high and low contact is possible and desirable. For “Cost Leader” type services, back-office activities are decoupled from the front office for the purpose of lowering costs. For “Personal Service” type services, back-office tasks are retained in the front office to pursue non-cost-oriented objectives. For “Kiosk” type services, all tasks remain in the front-office to save costs. For “Focused Professional” type services, front- and back-office activities are decoupled to enable front-office workers to provide higher service, rather than to reduce costs. Employ contact reduction strategies where appropriate. Employ contact enhancement strategies where appropriate. Employ traditional efficiency improvement techniques (TQM, BPR, etc.) to improve low contact operations, especially for Cost Leader services. 25 Customer Contact Behavioral Considerations Sequence effects: Customers carry away an overall assessment of an experience based on: The trend in the sequence of pain or pleasure The high and low points The ending Duration effects: People who are engaged in a task don’t notice how long it takes People will overestimate the time an activity takes Increasing the number of segments in an encounter lengthens its perceived duration Rationalization effects: People want things to make sense. If there’s no handy explanation for an unexpected event, they’ll concoct one. 26 Implications for Service Design Finish strong. Get the bad experiences out of the way early. Segment the pleasure, combine the pain. Build commitment through choice. Give people rituals, and stick to them. 27 The Service Encounter Triad Service Organization Control versus autonomy Efficiency versus satisfaction Contact Personnel Customer Perceived control 28 Structural Decisions Capacity Strategy Eight important factors to consider: Capacity is technologically based. Capacity depends on the interaction of multiple resource constraints. Capacity is mix dependent. Capacity can sometimes be stored. Capacity depends on management policies. Capacity is dynamic. Capacity is location specific. Capacity is affected by the degree of variability of demand and processing time. With demand and processing variability, lines may form even with excess capacity. As the average rate of arrivals approaches the average processing rate, system performance deteriorates rapidly and a capacity squeeze occurs. 29 Capacity Strategy Timing of Capacity Changes Policies: Lead demand with capacity Build to the forecast Add capacity only after demand exceeds it Mixed and/or nonstructural policies Determining the appropriate capacity cushion: Unit costs of excess/insufficient capacity 30 Capacity Strategy Sizing of Capacity Increments Economies of scale: Short-term – cost per unit output decreases as total output increases (i.e., spreading the overhead costs) Intermediate-term – increasing batch sizes (decreasing changeovers); dedicating resources to specific products, services, or tasks; using equipment that is specifically designed for the needs of a given product or service Long-term Diseconomies of scale: Static economies of scale – using one large facility or piece of equipment instead of a number of smaller ones to create a product or service Dynamic economies of scale – improvements in the total operating cost per unit that results from the skills, systems, and experience that accumulates over time Distribution, bureaucratization, confusion, vulnerability Increasing economies of scale: Network effects 31 Average cost/unit Optimal Economic Size Plant size 32 Capacity Strategy Approaches to Capacity Expansion Don't build additional capacity until the need for it develops Try to outguess the market by following a countercyclical strategy Build for the long haul Follow the leader(s) Question: How can a capacity expansion strategy be used proactively? 33 Developing the Supply Chain Insourcing vs. Outsourcing Considerations Pros Increased Insourcing control over price, quality, etc. Economies of combined operations Proprietary products protected Low capital costs Specialization Outsourcing Competition Increased flexibility Cons Capital costs Capability limits Time limits Opportunity costs Reduced flexibility to change partners Reduced volume flexibility Unfavorable allocation of product Lack of control over price, quality, etc. Lock-in from specialized contracts and assets Transaction (coordination) costs 34 Developing the Supply Chain Supplier Relations Competitive Orientation: Cooperative Orientation: The view that negotiations between buyer and seller is a zerosum game. Often used when a firm represents a significant share of the supplier’s sales or many substitutes are available. Example: WalMart The view that the buyer and seller are partners. Includes sole sourcing. Often used with strategically important and/or high value-added components. Example: McDonald’s Mixed strategy: Seeks to combine the advantages of the competitive orientation (e.g. low prices) with the cooperative orientation (e.g. few suppliers). Example: Toyota 35 Managing Supply Chain Relationships Long-term relationships Arm’s Length Characteristics When to use Non-strategic Short-term contracts Price sensitivity Minimal interface between firms Contractual safeguards are sufficient to enforce agreements Product is necessary but nonstrategic Commodity product Purchases account for a small percentage of supplier’s production Switching costs are low Low value-added Strategic Longer-term contracts Price sensitivity more broadly defined Minimal to moderate interface between firms Contractual safeguards are sufficient to enforce agreements Product is necessary but non-strategic Dividing purchases across multiple suppliers reduces the ability of suppliers to achieve significant economies of scale Vigorous competition can be achieved with few suppliers Switching costs are relatively high Low value-added Long-term contracts Relation-specific investments Supplier performance more broadly defined Self-enforcing agreements are necessary for optimal performance Components help to differentiate the customer’s product Customized, nonstandard products Multiple interaction effects with other inputs High degree of supplier/ buyer interdependence High value inputs 36 Strategic Management of the Supply Chain Efficient Supply Chains: Responsive Supply Chains: The purpose of efficient supply chains is to coordinate the flow of materials and services so as to minimize inventories and maximize the efficiency of the manufacturers and service providers in the chain. Efficient supply chains work best when demand is predictable and products/services are stable. Example of competitive priority: low cost. The purpose of responsive supply chains is to react quickly to market demands by positioning inventories and capacities in order to hedge against uncertainties in demand. Responsive supply chains work best when demand is unpredictable, new product introduction is frequent, and product variety is high. Examples of competitive priorities: development speed, fast delivery, customization, volume flexibility. In addition … Innovations in information technology and other practices are facilitating the integration of the supply chain for greater efficiency and responsiveness and enabling “orchestrated” networks. 37 Global Outsourcing and Offshoring Specific considerations: Capabilities/resources Coordination requirements Strategic control and risks 38 Designing the Multifacility Network Facilities Decisions Number Size Location Specialization (focus) By product line By production volumes By process stage By geographic region Layout Some key issues are efficiency, communication, and ergonomics 39 Managing the Multifacility Network Infrastructural issues Choosing and managing a network type: Horizontal network Vertical network Degree of (de)centralization: Centralized networks are more appropriate when different facilities: Produce similar products Serve similar customers who value uniformity Operate in similar environments with similar constraints and/or resources, especially in the presence of significant economies Decentralized networks are more appropriate when facilities: Produce different products Serve customers with different needs Operate in very different local environments 40 Supply Chain Dynamics Horizontal networks Vertical networks: The bullwhip effect is a tendency towards increased fluctuations in inventory and order levels as one moves back up the channel from the final customer. Some causes of the bullwhip effect include lack of visibility/communication throughout the supply chain, delays in information flows, ordering and shipping lags. The bullwhip effect can be alleviated by: Reducing the number of stages in the supply chain Communicating consumer demand directly up the supply chain Reducing ordering and shipping delays Reducing demand destabilizing practices Counter consumer “gaming” during shortages 41 Structural Decisions Process Technology Strategic implications of superior process technology implementation: Accelerated time to market Rapid ramp-up Enhanced customer acceptance Stronger proprietary position Key process development decisions: Approaches to integrating process and product development (e.g. design for manufacturability, prototyping) Timing of technology transfer to operations Locus of process development problem solving and learning by doing vs. learning before doing Degree of local autonomy for developing and changing processes 42 Incremental Improvement, Reengineering, and Productivity The purpose of incremental process improvement and reengineering is to move operations toward the performance frontier by: 1) eliminating non-value added activities and steps in the process and/or, 2) moving to a new performance frontier. Non-value added activities or steps can be characterized as waste (i.e., no potential to add value) or slack (i.e., resources in excess of what are required to get the job done, including buffers). The concept of “value added” can be thought of in the context of whether a customer would be willing to pay for that activity or step to be performed and/or whether a product or service’s value can be increased through that activity. Incremental process improvement involves eliminating non-value added activities or steps while leaving the current process essentially intact. Reengineering involves a fundamental rethinking and radical redesign of processes to improve performance dramatically in terms of cost, quality, service, and speed. Elimination of non-value added activities or steps increases productivity, by definition. 43 Sources of Non-Value Added Activities Why do non-value added activities or steps occur in processes? Poor process and/or organizational design (dysfunctional uncertainty) Historical artifact Barriers to learning Individual Within group Across groups From outside the organization To find and correct errors elsewhere in the process Unclear understanding of “value” and “risks” 44 Process Improvement Approach Discover where non-value added activities are in the process and prioritize improvement efforts: Flow charts (value stream mapping) Brainstorming Data collection Take action based on the source of the non-value added activity: Process reviews Remove barriers to learning Continuous improvement Reducing dysfunctional uncertainty Implementing a systematic approach to process improvement Increasing process knowledge Reengineering projects often take more of a “clean-slate” approach than incremental process improvement and are typically higher risk and higher return. 45 Plan-Do-Check-Act Cycle Plan Act Do Check 46 Six Sigma Principles Six Sigma Emphasizes the need to recognize high-impact, financially quantifiable opportunities and eliminate defects as defined by customers Recognizes that variation hinders the ability to reliably deliver high-quality products and services Requires data-driven decisions using a comprehensive set of quality tools Provides a highly prescriptive cultural infrastructure for aiding implementation When implemented correctly, promises and delivers $500,000 of improved operating profit per Black Belt per year The Define-Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control (DMAIC) improvement process used in Six Sigma is analogous to the PDCA cycle Six Sigma Organization Roles and Responsibilities •Own vision, direction, integration, results •Lead change Executive Champion Project Member All employees Green Belts •Understand vision •Apply concepts •Project owner •Implement solutions •Black Belt managers Master Black Belts •Full-time •Train and coach Black and Green Belts •Statistical problem solving experts •Part-time •Project-specific •Part-time •Help Black Belts Black Belts •Devote 50%-100% of time to Black Belt activities •Facilitate and practice problem solving •Train and coach Green Belts and project teams Lean Principles The lean approach to process improvement includes: A focus on customers (both internal and external) Maximizing process velocity (i.e., flow) Tools focused on analyzing process flow and delay times at each activity in a process Eliminating waste Separating “value-add” from “non-value-add” and addressing the root causes of non-value-add activities Reducing unnecessary complexity and its costs Lean Six Sigma Lean Six Sigma combines the emphasis on maximizing flows and reducing waste from Lean with variation reduction and an organizational infrastructure and specific improvement process from Six Sigma. Lean Six Sigma focuses on improving products and services by addressing poor flow and excess waste and variation in the process. Lean Six Sigma DMAIC Tools (Lean tools in bold) Define •Project selection tools •PIP management process •Value stream map •Financial analysis •Project charter •Multi-generational plan •Stakeholder analysis •Communication plan •SIPOC map •High-level process map •Non-value-added analysis •VOC and Kano analysis •QFD •RACI and quad charts Measure •Operational definitions •Data collection plan •Pareto chart •Histogram •Box plot •Statistical sampling •Measurement system analysis •Control charts •Process cycle efficiency •Process sizing •Process capability Analyze •Pareto charts •C&E matrix •Fishbone diagrams •Brainstorming •Detailed “As-Is” process maps •Basic statistical tools •Constraint identification •Time trap analysis •Non-value-added analysis •Hypothesis testing •Confidence intervals •FMEA •Simple & multiple regression •ANOVA •Queuing theory •Analytical batch sizing Improve •Brainstorming •Benchmarking •TPM •5S •Line balancing •Process flow improvement •Replenishment pull •Sales & operations planning •Setup reduction •Generic pull •Kaizen •Poka-yoke •FMEA •Hypothesis testing •Solution selection matrix •“To-Be” process maps •Piloting and simulation Control •Control charts •Standard operating procedures (SOPs) •Training plan •Communication plan •Implementation plan •Visual process control •Mistake-proofing •Process control plans •Project commissioning •Project replication •Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle Lean Systems A lean system is one which minimizes the cost of buffering (i.e., “best buffer”). Implementation Reduce the need for buffers Reduce excess buffers (uncertainty principle): (efficiency principle): Address dysfunctional uncertainty (e.g. poor quality, poor planning processes) More efficient responses to strategic uncertainty (e.g. cross-training, mass customization) Lower-buffer practices in stable and predictable environments (e.g. JIT) If buffers are needed, it is often possible to “swap” buffers (inventory, capacity, time) to minimize the disruption to the process/customer and provide the slack to address and eliminate problems. 52 Customization (Product Variety) with Standardized Operations (Mass Customization) Since customization (product variety) creates uncertainty in operations, and uncertainty requires extra resources, customization is more resource-intensive than standardization. However, it is sometimes possible to increase operational efficiency even with customization using standardization strategies (i.e., mass customization). Standardization strategies include: Part standardization – Maximize component commonality across products Process standardization – Delay customization as late as possible Product standardization – Carry a limited number of products in inventory 53 Creating an Improvement Strategy What are the pros and cons of the following improvement strategies? Tightly focused, top management-driven improvement programs: Single performance measure, dominant quadrant Single performance measure, multiple quadrants Broadly based, diffused improvement programs Top management directed, staged improvement programs 54