Dr. John Harris Office: BUS 207a - The University of Texas at Tyler

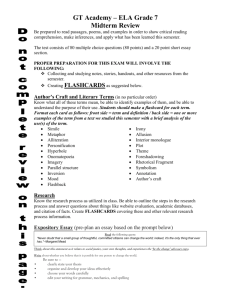

advertisement

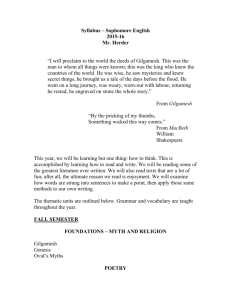

World Literature Survey I Dr. John Harris ENGL 2362.003 Spring 2014 Office: BUS 207a h: 903-566-4985 w: 903-565-5701 email: jharris@uttyler.edu Office Hours: MWF: 11-12:30 TTh: 8:30-9:30 Required Texts/Materials The Macintosh iPad (II) or other means (e.g., a laptop) of downloading PDF textbook All readings are in one large PDF download posted on Blackboard and a single short additional download (Gilgamesh): no bound texts are required, and no purchase of discs is necessary. Objectives: Any survey course seeks to provide an ample breadth of information (often, unfortunately, at the expense of depth). The objective in this class is for you to emerge with a general sense of major historical transitions in Western culture and of several significant authors whose work defined these transitions; furthermore, we shall aim to grow cursorily familiar with some of the world’s most influential texts and to understand how they relate chronologically and stylistically to our own traditions. Yet to suppose that we can even begin to cover all the world or all great literature, though the word “survey” be understood ever so broadly, would be presumptuous. (For instance, most of the non-Western works we shall study are Indo-Chinese: nothing from Japan, nothing from Africa, and just a bit from the Islamic world.) Hence my second general objective is based on the stylistic relationship mentioned above: you will acquire in this course a functional comprehension (which you will be able to apply to works and times not covered here) of the main characteristics distinguishing oral and literate cultures. The history of literature around the world has continually migrated along this spectrum, though at very differing rates. Hence the spectrum’s study is what the ancient Greeks would have called a “prolegomenon” (or necessary introduction) to the study of any complete literary tradition. I have accordingly broken this semester into three basic parts. First, through the ancient Greeks and Romans, we shall study how our own culture proceeded from an oral/tribal stage to a more literate/cosmopolitan stage; then we shall very briefly follow a similar sequence of stages in several Eastern cultures; and finally we shall return to Europe to observe how it achieved an unprecedented degree of literacy on the brink of what might be called modern times. I shall also strive to help you enjoy literature. The works of the past, especially those based in myth, frequently served religious, historical, and quasi-scientific ends without much thought to “aesthetic pleasure”, so we cannot simply assume that ancient authors intended to entertain us. Yet their assessment of religion, history, and science often turns out to be more aesthetic (that is, in search of an imaginative and poignant order) than they would have admitted. We need scarcely feel guilty, then, about stepping back and admiring the dream-like simplicity of their creations. In this course, you will learn how to unveil and admire the powerful narratives at work beneath odd or alien-seeming mythic surfaces. Finally, you will improve your analytical skills, not only through close reading and class discussion, but also and especially through writing. It is my particular objective that you continue your growth as thoughtful writers now that the freshman year is behind you. GRADING: Your grade will be determined through several means. Class Participation (50%): Because we have such a massive amount of reading material to cover and no classes to waste on formal exams, daily quizzes are the obvious choice for evaluating who is keeping up with the assigned reading and how well. A brief quiz will be administered at the beginning of almost every class. It will sometimes have a multiple-choice or matching format, sometimes a short-answer one. The questions should prove quite simple for those who have done their work. Naturally, the quizzes must determine this grade far more than any other factor. Yet I try to create opportunities for verbal participation in every class, and I appreciate and reward those who contribute in this manner. While I cannot weigh verbal participation nearly as much as I do the quiz grade (since spoken participation is very difficult to evaluate objectively), I regularly use notations in my grade book to indicate which students have shined during class; and I often find that some of these, by the end of the semester, have logged enough verbal points to pull their quiz average up a full letter grade. By the same token, sadly, a few students in recent years have proved so difficult to handle in class that I have also begun making deductions for rude, unruly, distracting, and otherwise disruptive behavior. My hope is that I will not have to subtract points a single time this semester—but I hold this defensive weapon in reserve. I must point out that physical attendance is vital for this half of your total grade. It should be plain to anyone that the kind of performance measured above requires students to be corporally present. Your quiz grade will plummet quickly with slack attendance, you will of course contribute nothing to our discussions, and you will also not collect important information that should be included in essays. My attendance policy is implicit in the foregoing remarks. Evaluating whether or not a student was truly ill or truly involved in a family crisis of truly detained by a faulty vehicle is beyond my ability. I prefer the simplicity of the positive measurement: the total points accumulated for class participation during the term. Athletes and other representatives of UT Tyler who must miss class to fulfill their obligation receive an adjustment in their average that corrects for missed quizzes: they need not worry about making these up. Essays (50%): You are required to write three essays in the course of the semester. The expectations of all three are very similar. Read the following descriptions carefully. Comparative/Contrastive Essay on Mediterranean Antiquity (15%): At the end of every section of readings is a list of paper topics. Each list is labeled in red, “Questions for This Section”. Some day my PDF may become a formal textbook: I am adding and refining these questions year in and year out with such an objective in mind. For now, however, some of the questions are better framed than others. Eight of these I have plucked out (sometimes slightly rewriting them) and listed at the end of the syllabus. I would like you to choose any one essay topic from these eight and compose a paper. The deadline for the first paper’s submission is March 6, our final class before Spring Break. You are encouraged to submit earlier: I will accept the essay at any time before this date. Comparative/Contrastive Essay on Persia/Indo-China OR Medieval/Renaissance Europe (15%): I have selected from a rather larger pool of questions in the PDF this time and produced eleven questions at the end of the syllabus. Again, choose any one topic. The deadline for this paper’s submission is May 1, or the final day of class. (You may have until the following Monday to compose the paper on Measure for Measure, since we shall only be finishing that play on May 1.) Final Paper (20%): In effect, this is your final exam. Here’s the assignment. You are asked to “build a bridge” across the class’s three broad units—Mediterranean Antiquity, Persia/Indo-China, and Medieval/Renaissance Europe—by focusing on one of the three cultural stages (oral-traditional, dialogicallegorical, or literate-progressive). You should choose at least one work from each of the three units that belongs to the stage you have chosen to analyze: two or three from each would be even more impressive. Describe your selected cultural stage by using these works as illustrations of its characteristics. Of course, the assumption is that, despite extreme differences in time and place, all works will share certain cultural tendencies. This is the point you are to develop. For instance, if you choose the “middle” stage, then you might reveal how the works of Virgil and Attar and Marie de France all show a distinct tendency to build an allegorical plot. The Final Paper should naturally run a little longer than the two previous essays. You may determine how much is adequate—but I would recommend five or six pages, at least. The same general rules for composing this essay apply as were outlined above for the first essay. Though the assignment is obviously broader, but your style should stay about the same. The essay is due by noon on May 6, either in my office or BUS 236 or via email. Writing Guidelines for Essays At the beginning of the PDF, you will find three “cultural profiles” that break down the essential stages of cultural evolution: oral-traditional, dialogic-allegorical, and literate-progressive. These profiles will be crucial in our attempt to make sense of a vast body of material coming to us from many parts of the world and from many eras. Review the profiles whenever you are pondering an essay topic. In the first two essays, you will be directed by whatever question you choose to select two or more works from our readings. The questions are all “comparative/contrastive” because their objective is critical analysis, NOT plot summary or historical scene-setting. Sometimes the amount of comparing and contrasting will be about equal. More often a specific question will instruct you that one kind of analysis should predominate. Always remember that your discussion should a) demonstrate an awareness of the cultural phases represented in the profiles, and b) refer fairly specifically to relevant evidence in the readings. Do not waste a lot of space citing lengthily from works: summarize as needed. Do not throw citations before the reader and expect that your understanding of their value will be transparent: explain. Do not worry about consulting outside sources to supplement your judgments: you should be putting your own thinking on display. Do not fret about cover pages, font, formatting, or other cosmetic details: I’m looking for substance, not tinsel. Do not redefine the question in the course of answering it: stay on target. A good paper will probably run about 1,000 words, or three to four pages. I do not say that it MUST do so. I offer only a ballpark figure here. Papers may certainly exceed these restrictions. More is not necessarily better, but very little is probably not very good. To repeat: none of these assignments is a research paper. You need make no trips to the library or visits to the Internet. They are exercises which call for judgment; that is, they do not so much express “right answers” as they measure how well you are able to correlate specific textual facts (whose selection is up to you) to very general criteria. Continually refer to the broad thumbnail sketches of the cultural transition from orality to literacy presented early in the PDF—the Cultural Profiles: these are your yardstick. The way you apply the yardstick will be crucial. Do the texts actually illustrate the points you raise about them (accuracy)? Have you indeed chosen useful illustrations, or are you just summarizing plots and “faking” your way through with airy formulations (clarity)? Do you connect the various points you raise in a coherent fashion (logical transition)? Do you use several points to develop your case rather than just one or two (thoroughness)? These four criteria will largely determine your grade. Papers may be submitted before the specified dates but will not be accepted after them without a legitimate excuse, preferably explained in advance of the deadline. Grade Replacement: “If you are repeating this course for a grade replacement, you must file an intent to receive grade forgiveness with the registrar by the 12th day of class. Failure to file an intent to use grade forgiveness will result in both the original and repeated grade being used to calculate your overall grape point average. A student will receive grade forgiveness (grade replacement) for only three (undergraduate student) or two (graduate student) course repeats during his/her career at UT Tyler.” 2006-08 Catalog, p. 35 Schedule of Readings and Assignments: Page numbers refer to the PDF posted on Blackboard for easy downloading: ALL readings are to be found in these files except for the modern translation of Gilgamesh and the selections from Grimm’s Fairy Tales (both available on Blackboard). Page numbers may be slightly off: always confirm the assignment by checking the author and title. January 14 Opening discussion covering “Profiles of Cultural Phases” (7-12). 16 Read 14-17 (“The Shaman as Hero”) and 640-654 (“The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn” from the Irish Táin Bó Cúalnge). 21 Read 18-29 (fragments from The Epic of Gilgamesh, Old Babylonian Version) and The Epic of Gilgamesh, Modern Translation (from PDF in Blackboard/Documents). 23 Read 42-61 (“Inklings of Complexity in Character and Society” and The Iliad of Homer, books 1, 6, and excerpt from 11). 28 Read 61-81: The Iliad of Homer (excerpt from book 16, books 22 and 24); also 82- 90, Homer’s Odyssey (book 1). 30 Read 91-115: Homer’s Odyssey (books 2, 6, 9-10). February 4 Read 127-133, 145-168: Homer’s Odyssey (books 13, 19-22). 6 Read 190-194 and 271-284: excerpts from “The Fables of Aesop”, Longus’ Daphnis and Chloe, and Apuleius’s Golden Ass. 11 Read 217-270: “Combining Old Pieces in New Ways” and Medea of Euripides. 13 Read 287-295 and 371-378: “Logic Revises Tradition”, selections from Plato’s Apology of Socrates, and “Scipio’s Dream” from Cicero’s De Re Publica. 18 Read 308-343 “Roman Energy Extends Greek Genius” and Virgil’s Aeneid, books 1-2. 20 25 27 Read 343-358: Virgil’s Aeneid (book 4, excerpts from books 6, 10, and 12). Read 371-386: excerpts from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Pliny’s Natural History. Read 387-394: selection from Tacitus’s Germania. March 4 Read 396-418:“Persia/Iran: Remnants of Oral Tradition” and excerpt from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh. 6 Read excerpt from Attar’s Conference of the Birds (download from Blackboard). First Essay Due (on Mediterranean Antiquity). 10S P R I N G 14 B R E A K. 18 Read 419-432 and 457-469: excerpts from 1001 Arabian Nights and from the Panchatantra and Somadeva’s Kathasaritsagara. 20 Read 470-497: Kalidasa’s Shakuntala Acts I-III (remaining acts discussed in class). 25 Read 558-581: Yüan Chen’s “The Story of Ying-Ying” and Wang Shifu’s Romance of the Western Wing (final act only). 26 Last day to withdraw from class. 27 Read 531-543 and 582-594: “China: Likenesses of Uncertain Beginning or End”; excerpts from The Analects of Confucius; and selected Chinese poets (T’ao Ch’ien, Wang Wei, and Han-Shan). April 1 3 8 10 15 17 22 24 29 May 1 6 Read 612-613 614-639, and 655-657: “The Middle Ages: Mythic Traditions Adapted to a New View of the Soul”, excerpt from Beowulf, and The Death of Aoife’s Only Son. Read 689-716: Marie de France’s Lay of Eliduc. Read 716-735, selections from Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Read 736-780: Owein, or The Countess of the Fountain. Read 820-842, 846-871: Dante’s Inferno (Cantos 1-5, 21-22, 26, 32-34). I recommend that you read one of several prose translations that are available free online. Read 873-888 and 951-961 (“The Renaissance: Alienation from the Past, Liberation to SelfDiscovery”, selections from Machiavelli’s Prince, and Montaigne’s “Of Cannibals”. Read 902-938: Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, excerpts from Cantos 1, 2, and 3. Read 962-979 and 990-995: Cervantes’ Don Quixote (Part 1, chapters 1-5; Part 2, chapter 17). Watch selections in class from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. Finish viewing Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, concluding comments about semester. Deadline for submission of Second Essay (Cultural Analysis paper). Deadline at noon for Final Paper (comparative or contrastive paper). Bring to BUS 207a, deliver to Lit. & Lang. Department at BUS 236, or send to reliable e-mail address. Mediterranean Antiquity 1. Illustrate thoroughly the essential characteristics of the shaman by referring to events in mythical narratives. Consider several ancient heroes who preserve some of the characteristics of this “liminal” type (e.g., Gilgamesh, Enkidu, Herakles, Achilles, Cú Chulainn, and even Medea). Use at least two such figures. 2. Compare and contrast the Achilles of the Iliad with the primitive figure of the shaman. What qualities does Achilles share with this figure? In what respects would his complexity as a more literary character be shortchanged if we labeled him merely a shaman like Gilgamesh or Herakles? 3. In the Iliad, Achilles appears to choose his own fate by opting for the glory of a short life of heroic deeds. Hector also seems to concede (in Book 6) that Troy is doomed to fall, and there were plenty of prophesies to that effect (such as his sister Cassandra’s). In the Odyssey, the Cyclops Polyphemus reveals that his blinding was prophesied, though he ignored the pronouncement, and we also find soothsayers predicting the hero’s return on several occasions. Discuss how this ancient Greek notion of fate or destiny places a major emphasis upon the conscious decisions that people themselves (and man-eating monsters, for that matter) make about their lives. In other words, explain how in this view we are “self-fulfilling prophets” who bring our own sad destiny to pass. If you are familiar with the Greek tragedian Sophocles’ play, Oedipus the King, that drama would also contribute some interesting examples to your discussion. 4. Something extraordinary is beginning to happen with the gods in Euripides’ Medea: they are disappearing. Though Medea is finally whisked away on a chariot provided by her grandfather Helios, this almost seems—in the light of everything else that happens—a metaphor for saying that the woman is a crafty survivor. Her personal will dominates the play; and indeed, Jason’s perverse ambitions and Creon’s naïve efforts to impose reason and order are also major motive factors. Discuss how this new universe of human choice plays into the emerging idea that people make their own destiny. How could the argument be made that Euripides really sees the invisible power behind human affairs as the irrational work of human psychological elements rather than the mysterious action of the Olympian gods? 5. Homer’s Odyssey is seldom viewed primarily as a romance, for a number of reasons; yet it certainly has some characteristics of that genre. Discuss the romantic elements of Odysseus’s tale in conjunction with some of the selections from ancient romances that we have read. Do you think the Odyssey possesses enough romantic qualities that we should reconsider classifying it as an epic? Explain your judgment thoroughly. 6. Socrates and Jesus were both executed as a result of their teachings. Clearly there are great differences between the two; nevertheless, a comparison of them on this ground is both possible and instructive. Explain what about their message and/or style so provoked the community in which they lived that both great men were condemned to die. Think carefully about the assumptions of that community, which in both cases was still clinging to oral-traditional ideas and habits. 7. The difference between the Stoical thought of Epictetus and that conveyed by Cicero through “Scipio’s Dream” is not the direct result of a timeline. Though Epictetus was actually the later figure, his thinking goes back more directly to Greeks of an earlier era (Zeno, Chrysippus, et al.) who built its foundation. What, then, are the basic distinctions between Greek and Roman Stoicism, and why do you believe that they exist? Consider the similarities shared by the two first so as to establish a broad definition of Stoicism. 8. Compare/contrast “Scipio’s Dream” and the Aeneid’s Book 6 with regard to their view of the cosmos. Begin by establishing similarities. Obviously, both visions place a premium on public service; both also refuse to concede that the individual soul simply languishes forever in a cold, clammy space after the body’s death (as in Homer’s Odyssey). Then proceed to the differences. How do Virgil and Scipio (Cicero) disagree when it comes to glory, empire, the ultimate end of the soul’s journey, etc.? Persia/Indo-China and Europe (Middle Ages and Renaissance) 1. Analyze the selections from Shahnameh according to the cultural profiles. The work seems to be resoundingly oraltraditional: is there anything about it which indicates that a shift is taking place into something more transitional? Draw overt parallels with works from Mediterranean antiquity like the Homeric epics—and you might profitably wait to answer this question, too, until we have read the medieval Irish Death of Aoife’s Only Son. 2. The Bhagavad Gita is an extremely complicated text. It seems to teach an inward-turning kind of spirituality such as we would associate with the literate mind; and yet, the result of such introspection is intended to be a renouncing of individuality and a suppressing of conscience in favor of traditional law (dharma). Krishna’s divinity embraces everything in a final revelation (not in our excerpt), implying a very nearly monotheistic belief system; yet the course of every person’s life is to conform strictly to the social niche into which he or she has been born. Evaluate this work in the context of cultural evolution: is it, in the final analysis, closer to a literate or to a traditional outlook? 3. Shakuntala is clearly a highly evolved romance. The drama’s focus is on the two lovers, and its dialogue primarily tracks their sentimental struggles and changes. The outside world of parents, formal duties, and even a cruel destiny doesn’t disappear—but the love of the king and his semi-divine “discovery” triumphs eventually (with supernatural help). Discuss these and other attributes of the play that make it a fine illustration of the romance genre. Refer occasionally to Daphnis and Chloe, the Aeneas/Dido romance, or other romance tales with which you may be familiar to give the discussion breadth. 4. “The Story of Ying-ying” is very probably a parody of the romance genre. Ironically, the long play, The Romance of the West Wing (of which you have been given only the final act), though composed about 400 years later, reflects an earlier stage of cultural evolution, when the romance was still taken very seriously. Contrast the two works. Which romantic elements treated in earnest by the play are exaggerated, understated, or otherwise distorted by the short story? 5. Compare T’ao Ch’ien’s poetic narrative, “The Peach Blossom Spring,” to Tacitus’s Germania. As your introduction explained, the two pieces, though separated by a vast gulf of time and space which no direct line of influence could have crossed, nevertheless evoke in similar manner a remote “Other World” space to imply that the “here and now” has degenerated and become almost unlivable. Discuss how the two authors make this very subtle case against the social and political realities of their time. (See Question 10 below for the same topic with a different focus.) 6. There are a few indications that the recorder of Beowulf is attempting to “upgrade” this pagan tale into a narrative more resonant with Christian notions of virtue. Discuss the features (from hints of a few words to adjustments of plot elements) that could possibly reflect this effort to take Beowulf beyond the parameters of the brawny, Gilgamesh-like superhero. Mention Gilgamesh, Herakles, or another such figure explicitly in order to sharpen up your contrast. As well as—or instead of—contrasting Beowulf with the crude shaman type, you may place your emphasis in the other direction. The Welsh Owein and Marie’s Eliduc have also been transformed from mythic figures into allegorical characters who imply a Christian lesson. How far along is Beowulf as such a literary construct when compared to them? 7. The Welsh romance Owain and Marie’s lay Eliduc are probably patterned upon the same mythic archetype (which we saw, too, in Kalidasa’s Shakuntala). Both involve a brave young knight who enters a strange land, proves his courage, wins a lovely lady’s admiration, and eventually blunders into neglecting his marriage. How can these medieval composers expect their audience to accept as heroic a figure who forgets about his new bride, in one case, and who actually schemes to possess a mistress, in the other? In what sense can such failed efforts at fidelity be styled heroic, or at least instructive? 8. Review Book 6 of Virgil’s Aeneid and then carefully consider the use Dante has made of its details in his epic’s opening cantos. Where do the Roman author’s figures and places crop up in the Italian’s Christian “re-write”? What do you think Dante is trying to signal his readers by representing some of Virgil’s vision as true yet clearly showing that the supernatural world exceeds the pagan author’s parameters? 9. As always when literacy spreads widely, we find parody rearing its head. Both Ariosto and Cervantes are clearly parodying the medieval notion of chivalry, yet they do not take the same approach in ridiculing the old chivalric romances. The former creates a universe (in the style called “burlesque”) where enchantments and Herculean physical powers in fact exist to the –nth degree, while the latter’s world (called “picaresque”) is a dreary parade of beggars, pickpockets, and confidence artists. Contrast the methods of the two parodists as they go about exploding the chivalric ideal. Do you think their basic message about that ideal’s flaws is the same, or significantly different? 10. Also common during periods of growing literacy is the transformation of the Other World Journey in such a way that it reverses polarities: that is, Hell becomes Arcadia and the living world becomes a pit of corruption. Montaigne very subtly takes shots at European culture as he explores a simple society on the globe’s far side. His work’s true objective may well be cultural self-criticism. Discuss the similarities between his methods and those used by Tacitus in describing the German “barbarians” and/or by T’ao Ch’ien in “Peach Blossom Spring”. 11. Discuss Measure for Measure as a species of Other World Journey. Who goes on an odyssey (more than one character, perhaps?) and what does he/she learn? Is the strange land visited a heaven or a hell? Make connections with other works in the centuries preceding Shakespeare. Besides romantic journeys like those in Owein and Eliduc, you might refer to political tracts like Machiavelli’s Prince. (This paper may be submitted as late as 5/5.) Students Rights and Responsibilities To know and understand the policies that affect your rights and responsibilities as a student at UT Tyler, please follow this link: http://www2.uttyler.edu/wellness/rightsresponsibilities.php Grade Replacement/Forgiveness and Census Date Policies Students repeating a course for grade forgiveness (grade replacement) must file a Grade Replacement Contract with the Enrollment Services Center (ADM 230) on or before the Census Date of the semester in which the course will be repeated. Grade Replacement Contracts are available in the Enrollment Services Center or at http://www.uttyler.edu/registrar. Each semester’s Census Date can be found on the Contract itself, on the Academic Calendar, or in the information pamphlets published each semester by the Office of the Registrar. Failure to file a Grade Replacement Contract will result in both the original and repeated grade being used to calculate your overall grade point average. Undergraduates are eligible to exercise grade replacement for only three course repeats during their career at UT Tyler; graduates are eligible for two grade replacements. Full policy details are printed on each Grade Replacement Contract. The Census Date is the deadline for many forms and enrollment actions that students need to be aware of. These include: approvals for taking courses as Audit, Pass/Fail or Credit/No Credit. l withdrawals. (There is no refund for these after the Census Date) -enrolled in classes after being dropped for non-payment ng the process for tuition exemptions or waivers through Financial Aid State-Mandated Course Drop Policy Texas law prohibits a student who began college for the first time in Fall 2007 or thereafter from dropping more than six courses during their entire undergraduate career. This includes courses dropped at another 2year or 4-year Texas public college or university. For purposes of this rule, a dropped course is any course that is dropped after the census date (See Academic Calendar for the specific date). Exceptions to the 6-drop rule may be found in the catalog. Petitions for exemptions must be submitted to the Enrollment Services Center and must be accompanied by documentation of the extenuating circumstance. Please contact the Enrollment Services Center if you have any questions. Disability Services In accordance with Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the ADA Amendments Act (ADAAA) the University offers accommodations to students with learning, physical and/or psychiatric disabilities. If you have a disability, including non-visible disabilities such as chronic diseases, learning disabilities, head injury, PTSD or ADHD, or you have a history of modifications or accommodations in a previous educational environment you are encouraged to contact the Student Accessibility and Resources office and schedule an interview with the Accessibility Case Manager/ADA Coordinator, Cynthia Lowery Staples. If you are unsure if the above criteria applies to you, but have questions or concerns please contact the SAR office. For more information or to set up an appointment please visit the SAR office located in the University Center, Room 3150 or call 903.566.7079. You may also send an email to cstaples@uttyler.edu Student Absence due to Religious Observance Students who anticipate being absent from class due to a religious observance are requested to inform the instructor of such absences by the second class meeting of the semester. Student Absence for University-Sponsored Events and Activities If you intend to be absent for a university-sponsored event or activity, you (or the event sponsor) must notify the instructor at least two weeks prior to the date of the planned absence. At that time the instructor will set a date and time when make-up assignments will be completed. Social Security and FERPA Statement: It is the policy of The University of Texas at Tyler to protect the confidential nature of social security numbers. The University has changed its computer programming so that all students have an identification number. The electronic transmission of grades (e.g., via e-mail) risks violation of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act; grades will not be transmitted electronically. Emergency Exits and Evacuation: Everyone is required to exit the building when a fire alarm goes off. Follow your instructor’s directions regarding the appropriate exit. If you require assistance during an evacuation, inform your instructor in the first week of class. Do not re-enter the building unless given permission by University Police, Fire department, or Fire Prevention Services.