The Economics of Baseball

advertisement

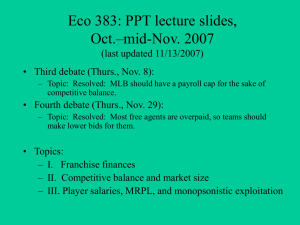

Eco 383: PPT lecture slides, Oct. 13, 2008 - ? (last revised 30 Oct. 2008) • Topics: – I. Franchise finances – II. Competitive balance and market size – III. Player salaries, MRPL, and monopsonistic exploitation Franchise Finances Franchise finances: An introduction • Why we care: – (1) To draw a conclusion about the health of the industry (MLB), we need to know about the health of individual firms (teams). – (2) Issue of whether the small-market teams can afford to field competitive teams. • If too many teams cannot compete, then demand for MLB will tend to fall. MLB’s 2000 report concluded that... • (1) 27 of the 30 MLB teams had cumulative operating losses in 1995-99. • (2) Small- and mid-market teams can’t compete, because they can’t afford to field very good teams. • Caveat: That was eight years ago. MLB officials say the picture is much brighter now. Computing team profits • OPERATING PROFIT • = total revenues total costs • same as “operating income” • what’s usually focused on • reported in Forbes (1997-), Financial World (1990-96) • PRE-TAX PROFIT • = operating profit interest costs* “player depreciation” • ≤ operating profit • declared to IRS • (* interest costs could be from purchase of team, stadium debt…) Ways to hide a team’s profits • Claim “depreciation” of your players as a loss (over 5 years, up to 50% of what you paid for the team; legal under U.S. tax law). • Deduct the interest paid on team-related loans. • Related-party transactions: If you own another company that does business with the team, overcharge your team (or pay it too little) in those deals. • Featherbedding: Pay yourself (and friends and relatives) an excessive salary and claim it as a cost. Breakdown of team revenues (Forbes, 1998) • 40% tickets & suites • 34% broadcasting • 12% food, merchandise • 7% ads, sponsorship • 6% other 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Tix B'cast Food Ads Other Breakdown of team costs In descending order of importance • • • • • • • Player salaries (~55% in 1992-2001) Scouting & player development (farm teams…) “General and administrative” Team operations (front office, manager, coaches…) Marketing, publicity, ticket operations Stadium operations (MLB revenue-sharing and general fund) – (Net cost for richer teams, net revenue for poorer teams) What is the return on owning a baseball team? • Operating profits are almost irrelevant… • As with a stock, most of the return comes from the long-term increase in the value of your asset (team). Desirable properties of investments • (1) High return, including – Short-term interest, dividends, or earnings – Long-term capital gain (can resell at profit) – Favorable tax treatment • (2) Low risk of loss • (3) Liquidity & cash flow – Liquidity = ease of resale; convertibility into cash – Cash flow = yearly stream of earnings (profits) Desirable properties of investments, as applied to MLB teams • (1) High return – excellent – But, over 1998-2006, NFL franchise values grew much faster, and NBA franchise values grew a little faster. • (2) Low risk of loss – excellent – Teams typically earn very high overall returns, with very few exceptions. • (3) Liquidity & cash flow – poor – Not liquid: costly and time-consuming to resell a team – Cash flow is small: yearly return on assets (operating profit as % of assets) is tiny, usually positive but < 2% Calculating a team’s (one-year) return on investment (ROI) ROI = % increase in estimated team value + (operating profit as % of previous year’s team value) Note well: Because operating profit is usually a very small fraction of team value, ROI will usually be very close to the one-year percent change in team value. To calculate ROI from the Forbes table The example below uses the data from the May 2006 Forbes ($1026 M value, a one-year change of 8%, operating income of -$50 M in 2005) to compute the 2005-2006 ROI for the Yankees -- Note: The denominator under operating income needs to be the previous year’s team value, which Forbes does not provide. You can get it by working backwards from the current year’s estimated value and the “1-year change in value” (percent change from previous year’s value). -- Ex.: Forbes says the Yankees were worth $1026 M in 2006, an increase of 8% (or .08) from 2005. The Yankees’ 2005 valuation was then ($1026 M)/(1+.08) = $950 M ROI .08 $$1 0502 6M M 1 .0 8 .08 $50 M $950 M .08 .053 .027 ( *100%) 2.7% Estimated one-year return on MLB teams (source: Forbes) Year Operating profit % increase in team value (return on assets) (return on investment) 1999 $1.0 million (0.5% of team value) 2000 $4.3 million (1.8% of t.v.) 6% (6.5%) 2001 $2.5 million (1.0% of t.v.) 10% (11.0%) 2002 -$1.3 million (-0.5% of t.v.) 3% (2.5%) 12% (13.8%) Estimated one-year returns, cont’d Year Operating profit % increase in team value (return on assets) (return on investment) 2003 -$1.9 million (-0.7% of t.v.) 3% (2.3%) 2004 $4.4 million (1.5% of t.v.) 15% (16.5%) 2005 $12.1 million (3.7% of t.v.) 2006 $16.5 million (4.4% of t.v.) 15% (18.7%) 14.8% (19.2%) Is the sky falling on MLB financially? • YES, said owners and commissioner (until very recently) • Selig: for 2001, a $232 M operating loss & $519 M book loss • several MLB teams were for sale in 200102, few buyers • NO, say most independent researchers • Forbes: for 2001, a $75 M operating profit • sluggish economy explains poor resale market in 2001-02 • franchises normally sell at big profits; high rates of asset appreciation Media ownership of teams • Ownership of teams by media companies, esp. TV stations, complicates the profit picture. – Media companies often buy teams as programming content, not as separate investments; synergy strategy. – Large operating losses may be OK if media company’s own profits go up. • Does this strategy work? Hard to generalize. – Past success stories include Ted Turner’s Atlanta Braves (TBS). – Yankees’ YES network, Red Sox’s NESN look successful. – Some media companies are selling, some are buying. • (Fox) News Corp. sold Dodgers, Disney sold Angels, Time Warner sold Braves. • Liberty Media Co. bought Braves. What a difference a year makes: Baseball finances improved dramatically from 2003 to 2004 (and still more in 2005-2007) 2003 2004 2005 2006 average operating -0.7% +1.5% profit (as % of assets) 3.7% 4.4% # of teams with 15 positive operating profit # of teams whose 17 estimated value rose 25 29 28 30 (only 1 fell) 30 20 What is competitive balance? • Blue Ribbon Panel report (2000): competitive balance exists when – “there are no chronically weak clubs because of MLB’s financial structural features” – a well-managed club has a reasonable hope of reaching postseason play and winning Why is competitive balance an economic issue? • The demand for MLB will tend to fall if-– too many teams cannot compete – fans perceive that the richest teams have an unfair advantage Simple measures of competitive balance • Standard deviation of team winning percentages • Number of WS or pennant winners, in comparison with-– number of teams in league – previous years or intervals • Average number of games out of first place? MLB’s competitive balance, then & now • • • • 1903-1950s: not much, but gradually improving 1965-1976: improved more; amateur draft helped 1977-early 1990s: peak of competitive balance 1995-2001: competitive imbalance? – strong correlation between payroll and W-L % and postseason • no teams outside top 25% of payrolls won WS • only 4 teams from bottom half of payrolls made postseason (and they won just 5 of 224 games) • 2002-2008 WS winners and payroll rank: Angels (15thhighest), Marlins (26th), Red Sox (2nd), White Sox (13th), Cardinals (11th), Red Sox (2nd), Phillies (13th) – 2002-2008 WS runners-up: Giants (10th), Yankees (1st), Cardinals (11th), Astros (12th), Tigers (14th), Rockies (25th), Rays (29th) Does a higher payroll mean more wins? (2002-2008) • Regressions of regular-season win. % on Opening Day payroll for all 30 teams find – – For 2008, statistically insignificant relationship • Payroll explains only 10% of the variation in wins in MLB • AL: < 3%; NL: 25% – 2002-2007: About 25% of the variation in wins is explained by variation in payroll • Actual variation in wins is much larger than payroll-predicted variation in wins • Payroll had a positive effect on wins, but smaller than one might think – $7-8 M in payroll = 1 more win – Marginal benefit of Yankees’ last $50 M in payroll = 0 wins? • Effect was small but statistically significant. What is “market size”? • Market size is based on REVENUES (both actual and potential). • Revenues are very dependent on the quality of the team’s product (wins, players, stadium, etc.), but also on local factors like – area population – area per-capita income – area level of interest in baseball (hard to measure) • Hard to separate team factors from local factors, actual from potential market size Two crude measures of market size • TOTAL REVENUES, as compared with the other MLB teams • ESTIMATED TEAM VALUE, as compared with the other MLB teams – more forward-looking, e.g., higher if team is about to move into new stadium • Top third = “large market,” middle third = “midmarket,” bottom third = “small market”? • Market size perhaps cannot be measured precisely Can the small-market teams compete? MAYBE • First 15 years of free agency (1977-91) saw unprecedented parity, several successful smallmarket teams • Insignificant correlation between payroll and W-L % through mid-1990s and in 2008 • Recent success of some small-market teams • Market size is not static MAYBE NOT • Yankees: 4 WS titles in 5 years (1996-2000) • 1997-2007: statistically significant correlation between payroll, W-L % • Only one small-market, low-payroll team has won WS since 1991 • Collapse of Montreal Expos (well-run smallmarket team) Competitive balance in recent decades • Recall: – 1977-early 1990s: peak of competitive balance – 1995-2001: some pattern of competitive imbalance • Explanations: – Free agency (post-1976) helped comp. balance • Easier for also-rans to improve themselves with new talent • Rising salaries --> harder to keep championship teams intact – Growing revenue and wealth imbalance in 1990s • Growing importance of local media and stadium revenues – Value of MLB’s national TV deal fell 60% in 1994 • Increasing corporate (esp. media) ownership of teams Competitive balance in other pro sports • (NFL) National Football League: highest comp. balance – lowest concentration of championships – policies: ~70% of revenues are shared; hard salary cap; “unbalanced” schedule – lowest correlation between payroll and performance • (NHL) National Hockey League: ???? – Pre-2004: in the middle: • low concentration of championships (1991-2002: 8 different teams) • little revenue sharing, no luxury tax, no salary cap • lower payroll-performance correlation than MLB or NBA – 2004-05: season-long lockout by owners, who got a salary cap • (NBA) National Basketball Association: least balanced – high concentration of championships (1991-2002: just 4 teams) – increasing standard deviation of win percentages since 1980 The English Premier League (PL; soccer) • League membership not fixed (non-monopolistic) – no territorial rights • London: 9 PL teams since 1990 • Within the league, a hierarchy of divisions – bad high-division teams are relegated (demoted) – good low-division teams are promoted to higher ones • Comp. balance is mixed – good in terms of standard deviation of win percentages, upward mobility of teams – high championship concentration (Manchester United) How can be MLB’s competitive balance be increased? • Payroll cap / luxury tax? – Payroll cap might work, but is not feasible -- players’ union willing to strike to prevent one – MLB has a luxury tax on large payrolls, but threshold is too high to be binding for most teams • Increased revenue sharing? – Could work, but details are key: • What if teams use accounting tricks to hide revenues? • Incentive for low-revenue teams to improve themselves? – Part of 2002 and 2006 Collective Bargaining Agreements (CBAs) • 2006 CBA keeps revenue sharing high, while supposedly providing better incentives for teams to improve themselves Player salaries, MRPL, and exploitation News flash: MLB players are highly paid • Average MLB salary = $3.2 M (April 2008) – More than 2 times as high as in 1998 – More than 10 times as high as in 1983 – Less than NBA ($5.4 M in 2007) – More than NHL (~$2 M in 2007) and NFL ($1.4 M in 2006) • Median MLB salary = $1 M in 2006, 2007, and 2008 – Highest ever; previous peak was $975,000 in 2000 – 85 players made $10 M or more in 200 • up from 66 in 2007 marginal revenue product of labor (MRPL) • = the amount of revenue that an employee generates for his employer • standard economic answer to “How much is that employee worth?” • can be measured in yearly terms (salary), or in hourly terms (hourly wage) • marginal product of labor (MPL) = how much OUTPUT an employee produces MRP theory & player pay • First, note that athletes are not the only very highlypaid people in U.S. society • Also, free-agent contracts are examples of VOLUNTARY EXCHANGE (market transactions agreed upon by buyer and seller) – Nobody forces the owners to pay such high salaries. • Rodney Fort: “talent is hired to produce [wins] in the long run.” – perhaps more than just wins... – Mark McGwire, 1998: extra MRPL of $15M? A labor market under perfect competition: Assumptions • Many buyers, many sellers – > nobody has market power • No restrictions on pay or employment • No cartels among employers or workers • Diminishing returns --> downward-sloping demand curve for labor • Upward-sloping supply curve for labor Notation (for diagram drawn on board): • • • • • L = # of workers ( = QL = quantity of labor) w = wage ( = PL = price of labor) SL = supply of labor DL = demand for labor MRPL = marginal revenue product of labor – MRPL = the amount of revenue that an additional worker generates for the firm Economic exploitation • MONOPSONY: a labor market with just one buyer • ECONOMIC EXPLOITATION • = difference between a worker’s marginal revenue product and his wage • = MRPL - w • In a monopsonistic labor market: • w < MRPL • w < w* (competitive wage) When the baseball players’ labor market was a monopsony • Until 1976, when all players were under the reserve clause. • RESERVE CLAUSE: a provision in baseball’s rules that allowed owners to renew a player’s contract automatically for one year. – Players either re-signed with their teams after each season or retired (or were traded or released). – No free agency; no competitive bidding for players. – Held salaries down; average salary = $25,000 in 1969. Independence Day • July 1976: new Basic Agreement gives all players free agency after 6 years of service. – Salaries surged after 1976; up 42% in 1976-77 – Can use monopsony diagram to illustrate Baseball’s current system Year of ML service Eligible for… 1st - 2nd Rookie minimum (Team can pay ($380,000 in 2007) more if it wants.) 3rd - 6th Salary arbitration After 6th Free agency Baseball’s salary explosion, 1976-present • “Freedom and prosperity” • Shift from monopsony to competitive bidding was less sudden than it seems – Over time, more and more teams played the FA market – Collusion against FA’s held salaries down in mid-1980s • Salary arbitration (1973-) allowed 3rd-to-6th-year players to piggyback on FA salary scale • MLB revenues surged -- attendance rose, TV revenues soared, stadium revenues soared, ... Comparison of performance (MRPL) and salaries • First, how to measure MRPL? For hitters, the one statistic that has the highest correlation with team winning percentages is... “OPS” • = On-base percentage (OBP) + Slugging percentage (SLG) • OPS * (player’s plate appearances as % of team’s) = what Zimbalist and Bradbury use to measure hitters’ productivity, in computing MRPL’s For pitchers • Earned run average (ERA) is the standard measure – Bradbury prefers “Defense-Independent Pitching Statistics” (DIPS), which is like ERA minus the contributions of the team’s fielders • Includes walks, strikeouts, and home runs allowed – Then compare a pitcher’s DIPS with the league average, and multiply by his innings pitched as a % of his team’s total. Next steps toward estimating MRPL • Estimate the player’s contribution to team winning percentage, based on wins as a function of OPS • Estimate contribution of additional wins to team revenues Comparison of performance (MRPL) and salaries: • Exploitation = MRPL – salary • Zimbalist (1992): – Younger players tend to be exploited (pay<MRPL) – Veteran players (6+ years in majors) tend to be “overpaid” (pay>MRPL) • MRPL calculations by Bill Felber (The Book on the Book, 2005) echo Zimbalist’s conclusion • MRPL calculations by Bradbury (p. 195) find pay<MRPL but a much smaller gap for veterans – But, “I don’t think this is exploitive,” if you take development costs into account. MRPL - salary, by service category MRPL – pay, on average (Bradbury, (Zimbalist; 2005; hitters, 1986-89) pitchers) Year of service Category 1st - 2nd reserved 75 – 84% (highly exploited) 89%, 90% 3rd - 6th arbitrationeligible 36 – 50% (exploited) 77%, 78% After 6th free-agenteligible -40% (overpaid) 8%, 36% How do we explain those systematically “overpaid”* veterans? • (* overpaid by Zimbalist’s and Felber’s estimates) • Supply and demand: limited supply of free agent players, high demand for players who can help a team • Most free agents are past their prime (age 30+), which reduces their MRPL, but as free agents they’re in a position to earn the most money • Statistical MRPL measure may be too narrow -- doesn’t count leadership, consistency, marquee value • Many free-agent contracts are long term – --> reduced incentive to work hard?